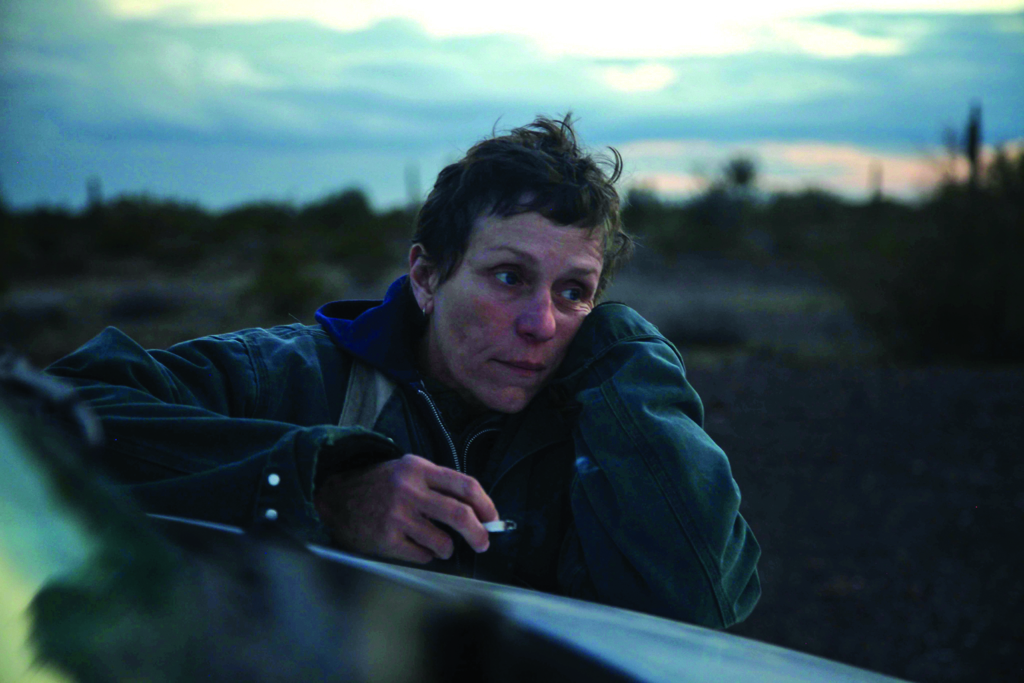

About five minutes into Nomadland (Chloé Zhao, 2020), protagonist Fern (Frances McDormand) enters an Amazon warehouse along with a stream of fellow workers ready to fill orders for the Christmas rush. Consistent with the film’s style of documentary realism, this episode was shot in a real-life Amazon ‘fulfilment centre’, and depicts groups of people working together as part of a well-oiled and relatively harmonious machine: the packing of boxes, scanning of items and carrying of tubs forming an unremarkable workaday rhythm. This on-screen Amazon is free of the repetitive strain injuries, concussions and pain-medication dispensers described by journalist Jessica Bruder in the book that inspired the movie.[1]Jessica Bruder, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty–first Century, W. W. Norton & Company, New York & London, 2017.

Amid the accolades bestowed on Nomadland, such as the Golden Lion at the Venice International Film Festival and six Academy Awards (including for Best Picture), an alternative, less effusive critical discussion has been generated by the film’s benign representation of Amazon’s workplace culture. The concern is that, while the book’s hard-hitting work of reportage exposes a ‘national catastrophe’ of dispossessed Americans struggling to survive, Zhao’s film is neutral – not just in its depiction of Amazon, but of the entire economy of desperation Bruder portrays. Critics of the film see an abandonment of social-realist critique in favour of an anachronistic narrative of individual freedom. But could it be that Zhao’s observational style and Fern’s detachment enact a rational response to an untenable situation? This is an eschewal of what Lauren Berlant describes as ‘cruel optimism’,[2]Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press, Durham, 2011. a way of living in the world based on an unachievable vision of future possibility. Fern has ‘adjusted’, in the terms suggested by Berlant, to a life of precarity, and the entire narrative of Nomadland might be considered a form of respite from imagining that one’s life can and needs to conform to a model of achievement and success. Berlant’s concept of ‘cruel optimism’ is particularly worthy of consideration in relation to other screen portrayals of Amazon-like workplaces and practices that connect with ‘the cinema of precarity’, a subset of screen narratives depicting ‘the present as a transitional zone, where the reproduction of inherited fantasies about what it means to have a good life is, to a certain extent, no longer possible’.[3]ibid., p. 201.

In this vein, the social realism of Guillaume Senez’s Our Struggles (2018) and Ken Loach’s Sorry We Missed You (2019) portrays the exploitative and precarious work practices that have led to the exponential growth of a new class of people without secure work or means of survival. In both films, the crisis state embedded in ordinary life is dramatised in the context of the nuclear family. The protagonists face the dilemma of working to support their families in jobs that compromise the families’ welfare but fail to deliver the monetary rewards associated with the legitimising myth of work ethic.[4]See Michell Speight, ‘Why People Work As Hard As They Do: The Role of Work Ethic as a Legitimizing Myth in the Work Lives of New York City’s Fast Food Workers’, dissertation, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, 2018, available at <https://www.proquest.com/openview/1c3f55c8a0b14206bbb27ad942c33b12/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750>, accessed 9 November 2021. In the case of Olivier (Romain Duris) in Our Struggles and Ricky (Kris Hitchen) and Abbie (Debbie Honeywood) in Sorry We Missed You, long hours and oppressive working conditions outside the home highlight the human cost of living and surviving in a state of precarity. This relates to a loss of security and predictability, or what media researcher Alice Bardan describes as ‘the condition of being unable to predict one’s fate’ – a state of living and being that affects all areas of a life, including ‘the availability of time for building affective personal relations’.[5]Alice Bardan, ‘The New European Cinema of Precarity: A Transnational Perspective’, in Ewa Mazierska (ed.), Work in Cinema: Labor and the Human Condition, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2013, p. 72.

Human machinery: Our Struggles

In Our Struggles, Olivier is a team leader in a large packaging-and-distribution warehouse. In the opening scene, he sneaks out of the house into the darkness of a winter morning while his family is still in bed asleep; it will be dark and past his children’s bedtime when he returns. The first shots of the warehouse represent a world of concentrated activity, where Olivier oversees his team’s operations with an intense focus and vigilance. A wide shot reveals the enormity of the operation, a labyrinthine grid of aisles and shelving that engulfs the workers as they move like clockwork through the space. These opening shots have a beauty and energy echoed by the soundtrack, which comprises the electronic dance rhythms of LCD Soundsystem’s ‘Oh Baby’. The mood changes with an abrupt cut to a conversation between Olivier and HR manager Agathe (Sarah Le Picard), who informs Olivier that she is not going to renew the contract of an older team member, Jean-Luc (Jeupeu), who can no longer keep up the pace. Within a moment, the energy of the preceding scene is transformed into a robotic functionality, and Olivier is faced with not only his friend’s disposability but also the reality of his own servitude within the organisation. Karl Marx’s description of capitalist production continues to apply in this twenty-first century workplace: ‘It is a common characteristic of all capitalist production […] that the worker does not make use of the working conditions. The working conditions make use of the worker.’[6]Karl Marx, cited in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p. 175. Olivier has been deluded in his belief that he leads a team, rather than a group of vulnerable individuals competing to keep their jobs. After being laid off, Jean-Luc kills himself, a chillingly rational ‘solution’ to his loss of market value.

Olivier’s struggle to cope exemplifies how family life and the duties of being a carer have increasingly become perceived as an interruption to work in the neoliberal economy.

As Olivier struggles with the challenges of his workplace, his wife, Laura, shoulders the burden of family responsibilities while also holding down a job. With few supports in place, she bears the main responsibility for both practical household duties and the emotional labour required to keep the family unit intact. As it eventuates, Laura’s waged work is essential to the material survival of the family, but has been made subordinate to the work taken on by her male partner. When Laura subsequently walks out, Olivier has to recalibrate his role in the family. He has no idea how to pick up the pieces of domestic life because Laura’s work in running the household has previously been invisible to him. Olivier is surprised to discover his young children need help to get ready for school, food to eat and clothes washed. Faced with the home duties that had previously been Laura’s responsibility, Olivier is confronted by the patriarchal power relations that, in macro-economic policy adviser Rania Antonopoulos’ words, ‘connect the “private” worlds of households and families with the “public” spheres of markets and the state in exploitative ways’.[7]Rania Antonopoulos, ‘The Unpaid Care Work – Paid Work Connection’, working paper, International Labour Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, May 2009, p. 2, available at <https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—integration/documents/publication/wcms_119142.pdf>, accessed 9 November 2021. As is revealed in Our Struggles, the dependency of the labour market on compromises and sacrifices made in the private sphere of the home is a huge pressure for families existing in a state of precarity, and Olivier’s struggle to cope exemplifies how family life and the duties of being a carer have increasingly become perceived as an interruption to work in the neoliberal economy.

Ironically, despite his long hours and dedication, it emerges that Olivier is not making enough money to cover the rent or afford warm clothes for his children. However, he has bought into a neoliberal work ethic that involves an overcommitment to – and identity-building investment in – his role as team leader. This leads him to counter his sister Betty’s (Laetitia Dosch) disparaging comments about his work by arguing that the effort of the team ‘all there pulling together’ is the ‘opposite of boring’. Olivier’s overidentification with his work blocks his capacity to demand change, something we see in his helplessness in response to decisions made by HR. Without the necessary distance from the work that dominates his and his family’s life, Olivier is blind to alternative measures of value. Hence, he pressures Betty to give up her life as an actor and come and live with him to look after his children. He tells her she has nothing to sacrifice – no job, no children, no husband. These are, of course, the pressures that Olivier’s wife Laura has fled, and it is notable how little condemnation her disappearance evokes, with a number of characters empathetically commenting that sometimes things just become too much to cope with and that maybe she ‘needs time to get things straight’. The need to endure and adjust to the precarious circumstances of ordinary life is communicated through the grim naturalism of the film’s mise en scène, with its dim, cold lighting and constrained spaces. The documentary intimacy of the handheld camera and the frequent close-ups contribute to the sense of struggle and confinement. The allure of escape from a life of constant pressure is communicated visually when Olivier travels to Wissant to look for Laura and pauses for a moment to gaze out to sea at a ship heading out from Calais. This rare wide shot of sun, sea and sky is a momentary release from the claustrophobic interiors and barren, wintry landscapes that otherwise build a sense of everyday life as bleak and strenuous.

The human machinery of Olivier’s workplace churns through tasks with speed and efficiency to process the goods required by the giant maw of consumer need. Yet the workers who play such a significant role in bringing these products to consumers struggle to make ends meet and have little purchasing power. Laura, who works in a dress shop, is overwhelmed by a friend’s despair at having her card turned down when trying to buy a garment. The dress has been framed as a special treat, offering the promise of individual transformation that comes with a new piece of clothing. The aborted purchase has the effect of knocking Laura off her feet as she is confronted by the reality of a life without the possibility of transformation. Unsupported by a fantasy of possibility, she can no longer sustain the image she has built of herself as a mother, friend and wife. Likewise, after Laura’s departure, Olivier’s struggle to manage both practically and financially is communicated through the family’s diet of cereal, the secondhand pullovers they wear and the utilitarian backpack eight-year-old Elliot (Basile Grunberger) is given as a birthday present. The consumers whose needs and desires are the raison d’être of Olivier’s work, in contrast, remain off screen, highlighting the chasm between them and the workers labouring to fulfil their needs. While Laura is overwhelmed by her empathetic response to a customer’s distress, the meaningful intimacy of their in-person relationship contrasts with the alienating disconnection of the distribution centre.

As is the case with the real-life Amazon in Nomadland, the colossal distribution centre in Our Struggles functions without the visible presence of upper management or of those profiting from the workers’ labour. Instead, ruthless HR manager Agathe has the job of imposing efficiencies that have been well documented within a range of contemporary workplaces.[8]See, for example, Colin Lecher, ‘How Amazon Automatically Tracks and Fires Warehouse Workers for “Productivity”’, The Verge, 25 April 2019, <https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/25/18516004/amazon-warehouse-fulfillment-centers-productivity-firing-terminations>; and Jodi Kantor, Karen Weise & Grace Ashford, ‘Power and Peril: 5 Takeaways on Amazon’s Employment Machine’, updated 16 June 2021, The New York Times, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/15/us/politics/amazon-warehouse-workers.html>, both accessed 9 November 2021. In keeping with the precarious nature of the work that she has overseen, she herself loses her job for reasons that are not clearly explained. Nevertheless, her absence opens up a position in HR for Olivier, a position that he is offered because of the goodwill he inspires in his team; perhaps Agathe’s draconian approach has become outmoded, and Olivier’s people skills are perceived to be a more effective way of building worker efficiency. While the HR position offers the higher wage that Olivier so desperately needs, he has an almost visceral reaction to the idea of overseeing his team in a management role. He chooses instead to leave his home and take up a position as a union delegate in Toulouse. In an ironically fantastical conclusion, Olivier’s struggle to survive is alleviated not by the union achieving fair pay and a living wage in the workplace, but by it endowing him with a well-paid position within the union structure. Our Struggles concludes with breathtaking speed as the family heads off into a future in Toulouse defined by hope and possibility. The upbeat ending, in which the family paints a parting message for Laura on the wall of their house, communicates their newfound capacity to connect through life-affirming creative solutions.

As is the case with the real-life Amazon in Nomadland, the colossal distribution centre in Our Struggles functions without the visible presence of upper management or of those profiting from the workers’ labour.

Striving in vain: Sorry We Missed You

In Our Struggles, Laura’s departure reveals how fragile and precarious the family’s shared life has always been; as Senez puts it, ‘Just like a house of cards, if you remove one, the entire thing collapses.’[9]Guillaume Senez, quoted in ‘Entretien avec Guillaume Senez’, Iota Production, Les Films Pelléas & Savage Film, Nos batailles press kit, 2018, p. 4, available at <https://medias.unifrance.org/medias/136/232/190600/presse/nos-batailles-dossier-de-presse-francais.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2021. Translated by author. The life of the family in Sorry We Missed You exists in a similarly fragile state: mother Abbie works as a carer on a zero-hours contract, while her partner, Ricky, picks up work on a casual basis. Unlike the people-pleasing Olivier, Ricky is not a team player, and is tantalised by the promised autonomy of being self-employed. Against the odds – as someone who lost his house in the 2008 financial crisis and has subsequently been unable to find work in his trade as a carpenter – Ricky continues to believe in the elusive rewards of the meritocracy of the free market, and he’d rather starve than be on the dole. Spurred on by a well-meaning friend, he decides to sign up as a franchisee for a high-powered parcel delivery service. In his ongoing belief – held in defiance of his actual lived experience – that risk and hard work will lead to economic security, he is buying into what political and social sciences researcher Brunella Casalini describes as ‘an “economy of promise”, in which the future seems to be the only temporal dimension that receives full attention’.[10]Brunella Casalini, ‘Care of the Self and Subjectivity in Precarious Neoliberal Societies’, Insights of Anthropology, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019.

To kickstart his new enterprise, Ricky needs a van, and, to pay the deposit, he persuades Abbie to sell the car she uses for her role as a careworker. The unthinking cruelty of expecting Abbie to travel by bus to care for her clients highlights the integral connection between patriarchy and the entrepreneurial spirit nurtured by the neoliberal marketplace.[11]For more on this topic, see Beatrix Campbell, ‘Neoliberal Neopatriarchy: The Case for Gender Revolution’, openDemocracy, 6 January 2014, <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/neoliberal-neopatriarchy-case-for-gender-revolution/>, accessed 9 November 2021. Abbie and the welfare of the family – as individuals and as a whole – become the collateral damage of Ricky’s optimistic fantasy of building a better life. When the narrative begins, the family is just managing to make ends meet, and everyday life requires constant adjustment and adaptation to ongoing and emerging pressures. Ricky feels emasculated by this struggle for survival, and there is more than a hint of the gambler’s desperation in his decision to blow his family’s very meagre resources on such a risky venture. Like a gambler, he is in thrall to a mirage of success, and applies a gambler’s wilful ignorance to the very many warning signs that are presented to him.

At the beginning of Sorry We Missed You, we hear Ricky before we see him – the film’s opening titles are underlaid by what sounds like a job interview. When the visual narrative begins, and as the interview proceeds, it emerges that Ricky is not being interviewed for a job but rather engaged in a transactional exchange taking place on a patently uneven playing field. The burly logistics manager, Maloney (Ross Brewster), is laying out the nature of the zero-hours agreement that Ricky is entering into with weasel words that have the power to invade Ricky’s life and destroy the very little that he and his family have:

Let’s just get a few things straight at the start, though, shall we? You don’t get hired here; you come on board. We like to call it ‘onboarding’. You don’t work for us; you work with us. You don’t drive for us; you perform services. There’s no employment contracts. There’s no performance targets. You meet delivery standards. There’s no wages, but fees. Is that clear?

Ricky eagerly sells himself to Maloney in a scene replete with dramatic irony – the viewing audience is left in little doubt about how and where this transaction will end. From the audience’s perspective, Ricky’s decision may seem irrational, but is in fact guided by a market economy that fosters the insecurity that encourages the desperate risk-taking he engages in.

Much like Agathe in Our Struggles, Maloney is a representative antagonist, standing in for and giving voice to the system he serves. He boasts that he is in service to the delivery tracking system, a ‘box’ that is ‘in competition with all of the other little black boxes round the country […] and decides who lives and who dies’. The efficiencies and penalties that Maloney enforces with such draconian and disciplinary verve are ministering to an operation based on speed and volume provided at a low cost. As a result of the tracking device monitoring not only where Ricky goes but also the time it takes him, the streets of Newcastle are transformed into a surveilled and dehumanised workplace that can be compared to the warehouse floor in Our Struggles. The difference is that, unlike Olivier, Ricky is an individualist with no investment in collective engagement. While Olivier cannot contemplate taking on an HR role that would raise him above his team, Ricky profits from Maloney’s ill treatment of a fellow driver by volunteering to take over his route. This choice of individualistic competition over collective solidarity seals the Faustian bargain that Ricky has entered into, and sets in train what might be considered his tragic downfall, whereby he loses not only the autonomy he holds so dear, but also his dignity as a human being.

As a result of the tracking device monitoring not only where Ricky goes but also the time it takes him, the streets of Newcastle are transformed into a surveilled and dehumanised workplace.

Abbie is similarly in thrall to the exigencies of the gig economy. She shoulders the lion’s share of family responsibilities while also trying to care for her clients as if they were family. Her work involves comparable hardships to Ricky’s: she works long hours with no time to eat, and, in addition, has no transport. Abbie also has to deal with the commodification of her clients’ care, which means she is only paid for an allotted amount of time regardless of the needs of her vulnerable clients. Her manager has none of the macho bluster adopted by Maloney, but is equally protective of a system that is based on the same economies of time and cost as the delivery company. However, in contrast to Ricky, Abbie is not convinced by a system that asks her to think of the people she cares for as clients to be serviced, and instead follows a rule of treating the people she cares for as she would her mother. This working principle benefits a system that expects people in caring professions, and women in particular, to do extra work to compensate for structural inadequacies (according to scholar Peter Bloom’s framework, this compensation would render Abbie an ‘ethical capitalist subject’[12]Peter Bloom, The Ethics of Neoliberalism: The Business of Making Capitalism Moral, Routledge, London & New York, 2017, p. 17.). By the same token, Abbie’s commitment to the humanity of her clients might also be seen as a form of resistance – one based on an understanding of an ethics of care that includes what Casalini describes as ‘a capacity to slow down, listen and think’.[13]Casalini, op. cit. That Abbie genuinely listens to the people she cares for and responds to their needs is demonstrated in a series of vignettes that include rearranging her timetable for a miserable young man reluctant to get out of bed, cleaning the excrement-covered walls of an elderly woman with dementia and sharing family photos with Mollie (Heather Wood), one of her favourite ‘old ladies’. Abbie’s gestures are an integral part of the authenticity with which she approaches her role, particularly the instinctive way she holds her clients’ hands. While Arlie Hochschild usefully coined the term ‘emotional labour’ to make visible the work required of people in caring professions who must evoke and suppress feelings as part of their job,[14]See Julie Beck, ‘The Concept Creep of “Emotional Labor”’, The Atlantic, 27 November 2018, <https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/11/arlie-hochschild-housework-isnt-emotional-labor/576637/>, accessed 9 November 2021. Abbie distinguishes her care for her clients from the transactional relationship of taking care of them.

The precarity of Ricky’s and Abbie’s work places unsustainable pressure on their family, with both of their children struggling under the emotional load of their parents’ stress. As in Our Struggles, the family that is the reason for the hard work is also the victim of its collateral damage. Berlant points out that this is a key relation of cruel optimism: ‘when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing’.[15]Berlant, op. cit., p. 1. In this vein, while Ricky is in thrall to his desire to build a secure future for his family, his son, Seb (Rhys Stone), can see through this fantasy: he is a witness to the exploitation inherent in his parents’ faith in the value of hard work, and is also cynical about the benefits of higher education when weighed up against the accrual of a massive debt. Like Betty in Our Struggles, he chooses to build a creative life in the present rather than invest in hope for the future. Both Betty and Seb are catalysts for a pause in the forward movement of their respective films’ narratives, in which they create space for their families to fully occupy the present and experience momentary release from their struggle to achieve a better life. In each case, this release into the present is accompanied by music. In Our Struggles, Senez chooses Michel Berger’s 1990 song ‘Le paradis blanc’ to introduce a moment of respite from words and conversation.[16]Senez, op. cit. In Sorry We Missed You, when a rare harmonious family dinner is interrupted by an emergency call from Mollie, Seb suggests the family drive Abbie to her client’s house. As the van pulls up, the whole family is laughing and moving to the beat of Young MC’s 1988 single ‘Know How’. It’s a temporary reprieve, and an interlude that leads to Ricky and Abbie articulating their feelings of fear and alienation as the security they crave slips further away from them.

The brutal market-focused rationalism that underpins both the gig economy and neoliberal systems of production, distribution and consumption has led to increasing social division as well as the emergence of a new class of people – the ‘precariat’[17]‘The neologism “precariat,” which blends “precarious” and “proletariat” (the working classes), refers to what Guy Standing calls a “class in-the-making” that lacks labor-related security and which results from the neoliberal insistence on labor market flexibility.’ Bardan, op. cit., p. 72. – connected through the social and economic insecurity that dominates their lives. In the three films discussed here, the efficiencies developed around ecommerce delivery become the locus for an exploration of cinematic representations of ordinary life in a time of crisis. In both Our Struggles and Sorry We Missed You, family love and other forms of human connection are portrayed as inseparable from the constant stress and insecurity that suffuses the ordinary crisis of everyday life. By contrast, in Nomadland, Fern’s emotional detachment contributes to her adaptation and adjustment to a life of precarity. Her blunted affect relates to grief and the loss of her husband, but the other nomads she encounters possess a similar neutral companionableness. Without the intensity and pressures of family and emotional commitment, they find a form of freedom in no longer hoping for the best.

Endnotes

| 1 | Jessica Bruder, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty–first Century, W. W. Norton & Company, New York & London, 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Duke University Press, Durham, 2011. |

| 3 | ibid., p. 201. |

| 4 | See Michell Speight, ‘Why People Work As Hard As They Do: The Role of Work Ethic as a Legitimizing Myth in the Work Lives of New York City’s Fast Food Workers’, dissertation, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, 2018, available at <https://www.proquest.com/openview/1c3f55c8a0b14206bbb27ad942c33b12/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750>, accessed 9 November 2021. |

| 5 | Alice Bardan, ‘The New European Cinema of Precarity: A Transnational Perspective’, in Ewa Mazierska (ed.), Work in Cinema: Labor and the Human Condition, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2013, p. 72. |

| 6 | Karl Marx, cited in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, New York, 1968, p. 175. |

| 7 | Rania Antonopoulos, ‘The Unpaid Care Work – Paid Work Connection’, working paper, International Labour Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, May 2009, p. 2, available at <https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—integration/documents/publication/wcms_119142.pdf>, accessed 9 November 2021. |

| 8 | See, for example, Colin Lecher, ‘How Amazon Automatically Tracks and Fires Warehouse Workers for “Productivity”’, The Verge, 25 April 2019, <https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/25/18516004/amazon-warehouse-fulfillment-centers-productivity-firing-terminations>; and Jodi Kantor, Karen Weise & Grace Ashford, ‘Power and Peril: 5 Takeaways on Amazon’s Employment Machine’, updated 16 June 2021, The New York Times, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/15/us/politics/amazon-warehouse-workers.html>, both accessed 9 November 2021. |

| 9 | Guillaume Senez, quoted in ‘Entretien avec Guillaume Senez’, Iota Production, Les Films Pelléas & Savage Film, Nos batailles press kit, 2018, p. 4, available at <https://medias.unifrance.org/medias/136/232/190600/presse/nos-batailles-dossier-de-presse-francais.pdf>, accessed 10 November 2021. Translated by author. |

| 10 | Brunella Casalini, ‘Care of the Self and Subjectivity in Precarious Neoliberal Societies’, Insights of Anthropology, vol. 3, no. 1, 2019. |

| 11 | For more on this topic, see Beatrix Campbell, ‘Neoliberal Neopatriarchy: The Case for Gender Revolution’, openDemocracy, 6 January 2014, <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/neoliberal-neopatriarchy-case-for-gender-revolution/>, accessed 9 November 2021. |

| 12 | Peter Bloom, The Ethics of Neoliberalism: The Business of Making Capitalism Moral, Routledge, London & New York, 2017, p. 17. |

| 13 | Casalini, op. cit. |

| 14 | See Julie Beck, ‘The Concept Creep of “Emotional Labor”’, The Atlantic, 27 November 2018, <https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2018/11/arlie-hochschild-housework-isnt-emotional-labor/576637/>, accessed 9 November 2021. |

| 15 | Berlant, op. cit., p. 1. |

| 16 | Senez, op. cit. |

| 17 | ‘The neologism “precariat,” which blends “precarious” and “proletariat” (the working classes), refers to what Guy Standing calls a “class in-the-making” that lacks labor-related security and which results from the neoliberal insistence on labor market flexibility.’ Bardan, op. cit., p. 72. |