In 2016, it came to light that a number of boys across various Australian schools had been involved in a series of cybercrimes against their female peers. Police were called in to investigate the sharing of nude images, including social-media pages set up specifically to encourage the secret acquisition and posting of illicit photographs – as well as stalking – of underage girls. One such Instagram account invited its followers to vote for ‘slut of the year’, and included images of girls as young as eleven.[1]Calla Wahlquist, ‘Police Investigate Private School Student over Alleged Sharing of Nude Images of Classmates’, The Guardian, 11 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/11/police-investigate-private-school-student-over-sharing-nude-images-of-female-classmates>, accessed 4 November 2020.

A little over twelve months later, the #MeToo movement gained traction after a couple of dozen women raised allegations of sexual assault and harassment against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein. Originated in 2006 by American activist Tarana Burke, the #MeToo hashtag provided the opportunity for survivors of sexual assault and harassment to come together and speak out publicly. An avalanche of accounts by everyday people – emboldened by the Hollywood disclosures – of experiences of sexual aggression filled social-media pages, leaving many men bewildered that so many of the girls and women in their lives had experienced such treatment.[2]See Nadia Khomani, ‘#MeToo: How a Hashtag Became a Rallying Cry Against Sexual Harassment’, The Guardian, 21 October 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/20/women-worldwide-use-hashtag-metoo-against-sexual-harassment>, accessed 4 November 2020. Of course, these disclosures were no such surprise to women, and there was a commonly held sense of catharsis and relief that the lid had been lifted on the misogyny underpinning this scourge of societally rampant harassment and abuse.

As schools began to roll out their Respectful Relationships curriculum and programs like mine[3]See SEED Workshops website, <www.seedworkshops.com.au>, accessed 4 November 2020. were taken up in droves, filmmakers began to tell these stories of online exploitation, cyberbullying, consent, respect and toxic masculinity. In August 2019, on the heels of Greta Nash’s award-winning short film Locker Room (2017),[4]Locker Room can be viewed on Nash’s website; see <http://www.gretanash.com/locker-room>, accessed 4 November 2020. SBS TV released The Hunting, a four-part miniseries exploring the impacts and consequences of the acquisition and sharing of nude images of underage girls. Set between two secondary schools, The Hunting follows the lives of four students and their teachers and families as they grapple with the legal, ethical and cultural ramifications of what has become a real-life nightmare for many in the digital age. As an educative tool, the series provides plenty of opportunities for reflection and discussion in the classroom and at home.

Prior to students viewing the series, it should be noted that it has an M rating and contains sexual references and sex scenes, coarse language, nudity, adult themes, and dangerous stunts. From the opening scene, the content is quite confronting, and the themes explored could trigger traumatic reactions for students who may have experienced similar online sexual harassment and bullying, so it’s important to set up a safe space and ensure students have access to wellbeing services should they wish to discuss and/or disclose their own experiences. Students who wish to report cyberbullying and image-based abuse should contact the Office of the eSafety Commissioner.[5]See ‘Report Abuse’, Office of the eSafety Commissioner website, <http://esafety.gov.au/complaints-and-reporting>, accessed 4 November 2020.

Given the nature of the content, it is recommended that the questions accompanying each episode be addressed as a class group unless there is adequate teacher supervision for smaller breakout groups of students.

Episode 1: ‘Pics or It Didn’t Happen’

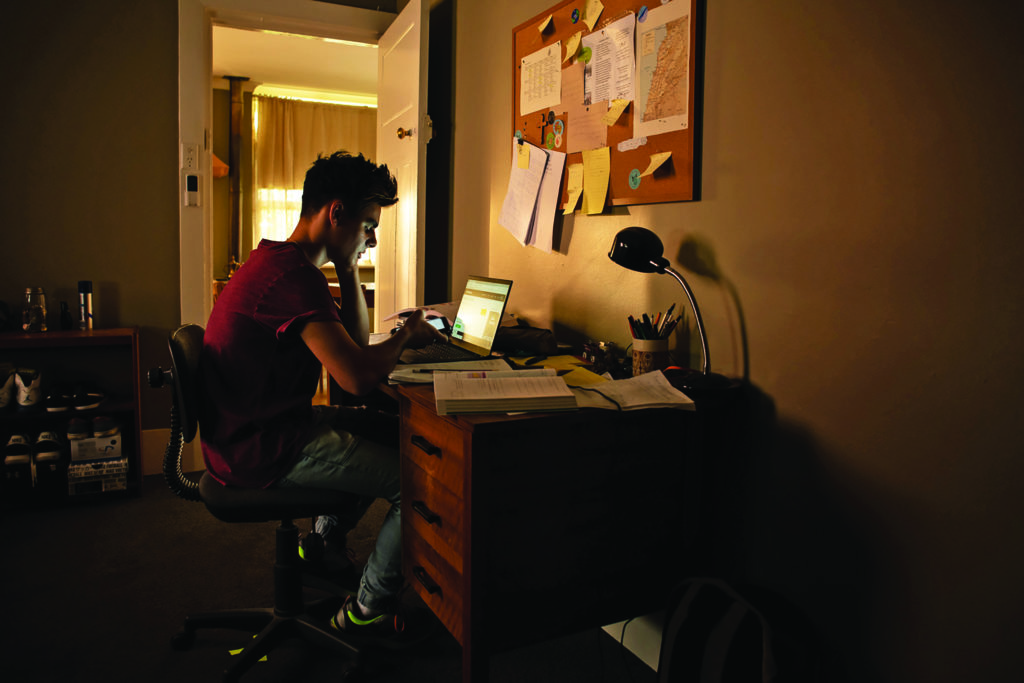

Prior to the opening credits of the first episode, we see teenagers Zoe (Luca Asta Sardelis) and Andy (Alex Cusack) engaged in cybersex through a computer screen: she is masturbating while he watches and appears to reciprocate. Andy asks Zoe to position herself so he can see her better, and we notice that he is screen-recording. This raises a few questions for students to consider:

• Should Andy have asked for Zoe’s permission to record?

• When asked to move further into view, should Zoe have known Andy might record her?

• Should Zoe have specifically asked him not to record?

• Activity: Apart from certain exemptions, various laws across states and territories prohibit the secret recording of another person. Research the relevant laws and penalties for unlawful recording in your state or territory.

We’re soon introduced to Andy’s friend from another school, Nassim (Yazeed Daher), who shares his school-bus ride and lunch with Andy. Andy encourages Nassim to make a move on a girl he likes.

At Nassim’s school, we are taken to a classroom where a ‘dick pic’ that another boy shared with a girl is being shown to the rest of the class. There’s laughter as the phone is confiscated, but the boy is clearly distressed and feeling humiliated. Principal De Rossi (Pamela Rabe), in conference with assistant principal Eliza (Jessica De Gouw) and new teacher Ray (Sam Reid), declares that students should know that the sharing of nude images is against the law, and that authorities should be notified as per mandatory-reporting laws.

• Are there differences when a boy’s (as opposed to a girl’s) private image is non-consensually shared?

• Is De Rossi right in her assertion that students should know the law? How would they know?

• What is mandatory reporting, and why does it exist?

• Do you think that someone who shares their own ‘dick pic’ deserves to be reported?

• Is it possible that mandatory reporting prevents people from coming forward for fear of police involvement?

• Activity: Research mandatory-reporting laws in your state or territory.

The Hunting presents us with a variety of family set-ups in which race, class, sexuality and privilege appear to impact on parenting styles.

At Zoe’s school, a contentious issue is gendered uniforms. We meet Zoe’s mothers, who encourage her to organise a protest about the lack of gender-neutral options.

• How much do school uniforms and policies contribute to outdated gender stereotypes and expectations?

• Zoe and her friends stage a demonstration. How else could students elicit change at their school?

• Activity: Investigate your school’s uniform policy and identify areas in which it could be improved to promote gender equity.

The Hunting presents us with a variety of family set-ups in which race, class, sexuality and privilege appear to impact on parenting styles. As we meet Nassim’s crush, Amandip (Kavitha Anandasivam) – Dip, for short – and her strict Sri Lankan parents, we get a sense of the care and trust between them, but also indications of cultural and generational division.

• How much of a role can parents play in helping prevent their children from becoming embroiled in online controversy?

• What are some barriers to parents getting through to their kids?

• Who would be the first person you would go to if you were subjected to image-based abuse?

• Activity: Research the organisations available to support victims of image-based abuse.

Andy appears embarrassed to witness Zoe’s feminist demonstration and disgusted at seeing her male friend dancing with her in a school dress. Soon after, he shows the video he recorded of her masturbating to his mates.

• Why does Andy decide in that moment to show his classmates the video of Zoe?

• What could a bystander’s role be in such a situation?

After their date at the beach, Dip sends Nassim a nude selfie captioned ‘for you until next time’; but later, when he tells Andy about it and Andy goads him, ‘Pics or it didn’t happen,’ Nassim forwards Dip’s photo on to him.

• What compels people to share images meant for their eyes only, and why was it so important to Nassim to prove himself to Andy at Dip’s expense?

• If Nassim can betray Dip’s trust, why does he think Andy won’t betray his?

By the end of this episode, after seeing Dip’s nude image on Nassim’s phone and telling him to delete it, Ray has confiscated Nassim’s phone overnight without reporting what he has seen, resulting in a breach of the school’s staff code of conduct. Further, having discovered Dip’s image on a social-media account named ‘Our Local Sluts’, he takes it into his own hands to control the damage, landing himself in even deeper hot water. At this stage, he is unaware that it was Andy who uploaded the image. Andy has also posted the video of Zoe in retaliation for her earlier rejecting him at the pool, when he raised awkward questions about the pregnancy between her two mothers.

• Who is Ray trying to protect here?

• Should the sharing of consensually acquired intimate images of teenagers be considered a criminal offence?

• Could Andy sharing the video of Zoe to this website be considered ‘revenge porn’? If so, ‘revenge’ for what?

Episode 2: ‘DTF?’

A printout of a video screenshot of Zoe has been pasted to her locker with the phrase ‘fuck a feminazi’ scrawled across it, and events continue to escalate throughout this episode as Zoe and Dip become aware that their images have been shared online.

• When Zoe confronts Andy about sharing the image and asks him if he hates women, he tells her that she’s starting to sound insane. Is this gaslighting?

• How would it feel to discover that your image has been non-consensually shared online?

• What is the meaning of feminism, and why are some people so hostile towards it?

• Consider the following statement: ‘I believe that the social, economic and political rights of women should be equal to those of men.’ Do you agree with this? Discuss why some people call feminist girls ‘feminazis’, and what it means when people say ‘feminism has gone too far’. By definition, if feminism goes ‘too far’, is it still feminism?

Ray sends the boys to the library while he addresses the girls. He tells the girls they must stop sending ‘nudes’, as they can’t control what the boys will do with them once they’re out of their hands.

• Is this victim-blaming or good advice?

• What advice should Ray give the students?

When young men are accused of sexual misconduct, it is by no means unheard-of for fathers to go into bat for them with little regard for their victims. In one famous instance in the US, the six-month prison sentence of twenty-year-old Brock Turner for sexually assaulting an unconscious young woman was referred to by his father in a court statement as ‘a steep price to pay for 20 minutes of action’ – a comment that was met with widespread condemnation.[6]Elle Hunt, ‘“20 Minutes of Action”: Father Defends Stanford Student Son Convicted of Sexual Assault’, The Guardian, 6 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/06/father-stanford-university-student-brock-turner-sexual-assault-statement>, accessed 4 November 2020. In some cases, parents and teachers have also attempted to subvert the course of justice, at least in part to prevent their own shortcomings from being exposed. In another US case in 2013, four adults connected to the high-profile Steubenville High School rape trial in Ohio – in which video footage had been taken of a series of assaults by male students against an unconscious female victim and posted online – were arrested for attempting to help cover up the incident.[7]Tara Culp-Ressler, ‘Four Adults Charged with Helping Cover Up the Steubenville Rape Case’, Think Progress, 25 November 2013, <https://archive.thinkprogress.org/four-adults-charged-with-helping-cover-up-the-steubenville-rape-case-ff77291aeb5a/>, accessed 4 November 2020.

The Hunting shows us parental bias of this kind through the behaviour of Andy’s obnoxious and sexist father, Nick (Richard Roxburgh), who laughs when he sees Zoe’s ‘feminazi’ image and insists his son’s involvement in the incident be referred to as ‘alleged’. Encouraged by his father’s support, Andy denies having recorded Zoe and suggests she does this kind of thing with other boys. Upon arriving home, Nick finds the material on Andy’s hard drive and confronts him about it, before giving him a ‘boys will be boys’–style lecture – one that is far more fixated on his stupidity in getting caught than on the ethics of what he did – and removing the evidence from the computer. Nick then lies about what happened to his wife, Simone (Asher Keddie), who appears to suppress her suspicions in favour of keeping the peace and protecting her son.

• Why would a parent protect their child from accountability under these circumstances?

• What is Andy’s father teaching him?

• Why didn’t Andy’s father speak with him about respect and consent?

By the end of this episode, we’ve witnessed two different approaches by two different schools to the same issue; Dip’s mother has become aware of the situation and told Dip not to tell her father; Dip has created a fake profile for ‘Our Local Sluts’ in an attempt to have her image removed, only to cop a barrage of abuse; and the police have arrived.

Episode 3: ‘#shittyboys’

Victims of image-based abuse often feel powerless against their perpetrators. A study by RMIT University for the Office of the eSafety Commissioner found that one in five Australians had been victims of revenge porn in some way.[8]‘One in Five Australians Is a Victim of “Revenge Porn”, Despite New Laws to Prevent It’, media release, RMIT University, 23 July 2019, <https://www.rmit.edu.au/news/all-news/2019/jul/revenge-porn-laws>, accessed 4 November 2020. The introduction of new laws (in all states except Tasmania) doesn’t seem to have provided much of a deterrent.[9]See ‘What’s the Law in My State or Territory?’, Office of the eSafety Commissioner website, <https://www.esafety.gov.au/key-issues/image-based-abuse/legal-assistance/law-in-my-state-territory>, accessed 4 November 2020. When it comes to the ‘dick pics’ and nude selfies of minors commonly shared among young people, State and Commonwealth legislation classifies such images as child-abuse material and prohibits their possession, dissemination or production. In some jurisdictions, an image of a fully clothed teenager in a sexual pose may be considered unlawful.

• Activity: Investigate the laws and penalties in your state or territory pertaining to revenge porn and child-exploitation material.

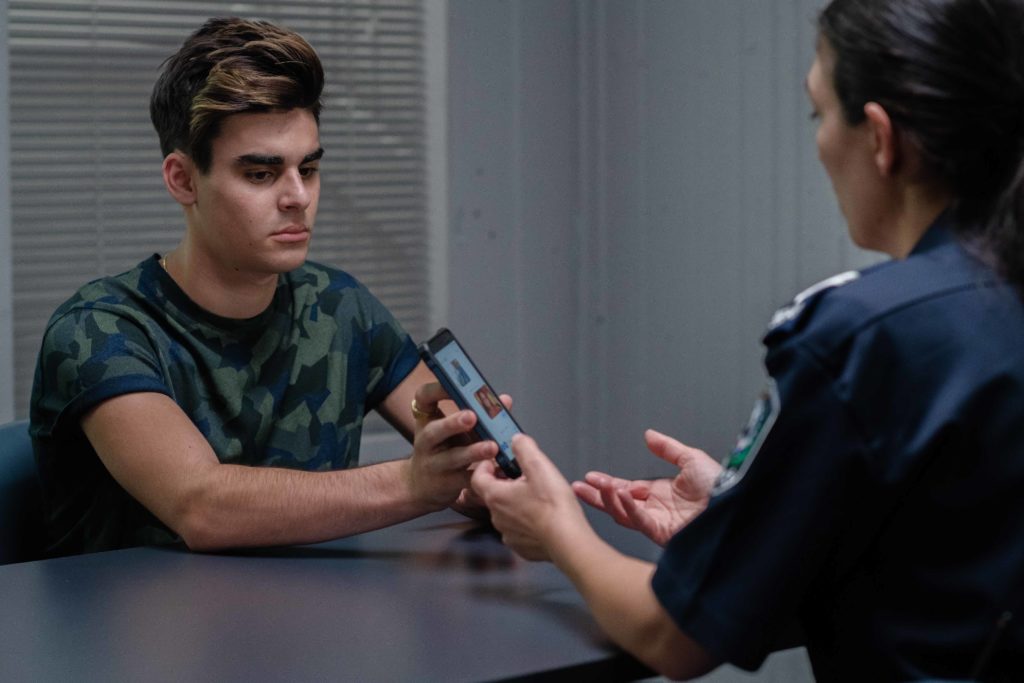

When Andy is questioned by police and told that, even though his laptop has been cleared, it may still contain traces of evidence of child-exploitation material, his father steps in yet again to rescue him from investigation. Cocky that he has evaded prosecution and gotten away with just a caution, Andy snarls, ‘The hunt is on, bitch,’ as he and his peers go searching for more victims to upskirt and upload. Later in this episode, during a conversation about the change in Andy and his increasing disrespect towards his mother, Nick tells Simone, ‘Yes, he’s crossing the bridge to manhood, but the last thing he wants is his mother holding his hand.’ She replies, ‘Well, who’s going to guide him? And what kind of man do you want our son to become?’ – both great questions.

• Why is Andy becoming more misogynistic?

• Is it true that boys don’t want their mothers’ guidance past a certain age? Why isn’t the same said about girls and their fathers?

• Is it too late for Andy to change? What might help him change?

• What kind of man might Andy become if he doesn’t change?

Meanwhile, at Nassim and Dip’s school, De Rossi has organised a cybersafety expert to talk to the students, but in her preceding speech she ends up devoting more attention to the length of the girls’ uniforms and the colour of their bras.

• Do young people take these assemblies and the advice of cybersafety experts seriously?

• What strategies can help get the message through?

It is commonly reported by victims of online image abuse that police are often slow to intervene, if they do at all, and that results vary depending upon the circumstances and host country of the website.[10]See Matilda Boseley, ‘Revenge Porn in Australia: The Law Is Only As Effective as the Law Enforcement’, The Guardian, 9 May 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/may/09/revenge-porn-in-australia-the-law-is-only-as-effective-as-the-law-enforcement>, accessed 4 November 2020. So it is unsurprising that, after dissatisfaction with police efforts, Zoe attempts to take matters into her own hands. After she creates her own post about Andy and his behaviour under the hashtag #shittyboys, the news soon gets back to him, prompting Simone to threaten her with legal action for defamation and tell her that this could have a terrible impact on Andy’s future. Although Andy organises his mates to bully and harass Zoe further, eventually at least one girl feels emboldened by the post to come forward and share her own story of abuse.

• It is reasonable for Zoe to take this action against Andy?

• Is Simone right that Zoe’s post is defamatory?

• Would this post impact on Andy’s future, and if so, how?

• What alternative responses could Andy and Simone have offered to Zoe’s post?

• What empowers other victims to come forward when someone else does?

In contrast to Zoe’s parents, who have been supportive and progressive, Dip’s conservative parents shame and punish her for the embarrassment they perceive she has brought upon their family. This provides an opportunity for students to consider that victims can have their trauma magnified depending on their particular family dynamic and parents’ expectations. Well-meaning comments from friends can also reinforce harmful narratives. Dip’s friend chastises her for leaving her face in the photo, and her teacher tells her, ‘You made one mistake. Be kind to yourself.’

• What are the differences between the ways Zoe’s and Dip’s families respond?

• Were Zoe’s actions any more or less shameful than Dip’s?

• Who decides what’s shameful?

• Did Dip make a mistake in leaving her face in the photo and sharing it with Nassim?

• Why is nudity as self-expression so stigmatised in our society, and why is the release of nude images considered to be so damaging, especially for girls?

By the end of this episode, Zoe and Dip have met each other for the first time, and Nassim has agreed to accompany them to the police station to report Andy’s sharing of Dip’s photo. Showing complacency at first, the police tell them they’ll need a parent or guardian to accompany them to give a statement. Unable to involve her parents, Dip calls Ray, who obliges. They are all shocked when police charge Dip (along with the boys) with producing and distributing child-exploitation material.

Episode 4: ‘Sluts’

In another teacher-conduct breach for which he is reprimanded, Ray shares his personal mobile-phone number with Dip. A hearing is held at the juvenile court, in which the judge says that one image shouldn’t be enough to ruin three young lives, and lets Dip, Nassim and Andy off with a verbal warning. Later, Andy attends a strip club with his father, while his mother calls his younger sister, Rosie (Isabel Burmester), a slut when she catches her trying on a slinky dress, applying make-up and taking selfies.

Simone returns home later that evening to find the messages ‘shame’ and ‘love, your local sluts’ written in lipstick across the glass doors leading to the pool, where Zoe, Dip, Nassim and friends have broken in and taken a swim. As her eyes meet the girls’, a moment of understanding crosses her face. Later, when Rosie asks her mother what the word ‘slut’ means and why the girls chose to refer to themselves as such, Simone explains its history and promises to never use the word as a pejorative again.

• What is a ‘slut’?

• Is there a male equivalent of the term? Does it hold the same weight, and if not, why not?

• What does it mean to ‘reclaim’ a derogatory slur?

In the pool, Dip has taught Nassim a lesson about trust by gaining his and then leaving him to almost drown. The impacts of his indiscretion have been immense for her, including her parents prohibiting her from attending Ray’s advanced-maths class. She decides she will do what is best for her, not what her parents think is best, however, and continues with the class. Zoe’s last hurrah before leaving her school for another is to confidently run through the building naked. Her parents are as proud as punch. Eliza runs some workshops about gender equality, and asks the boys and then the girls to list the things they do to keep themselves safe. The difference between the two groups’ responses is profound, and we get the sense that the boys appreciate the opportunity to hear what girls experience.

It seems unfair that the show’s main perpetrator, Andy, is ultimately the only one not held to account in any way, but it is a reflection of a society in which girls are often scapegoated for the actions of boys. The Hunting provides an excellent example of how many relationships can be affected by these kinds of betrayals of trust. It also asks us to consider how we might raise young people to be more mindful of actions and outcomes – not just legal, but ethical too. The consequences may not always be the ones we want or expect – and it seems we still have a long way to go on that front – but if we can teach them how to have healthy and respectful relationships and to avoid making harmful decisions, we’ll be on the right track.

Endnotes

| 1 | Calla Wahlquist, ‘Police Investigate Private School Student over Alleged Sharing of Nude Images of Classmates’, The Guardian, 11 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/aug/11/police-investigate-private-school-student-over-sharing-nude-images-of-female-classmates>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Nadia Khomani, ‘#MeToo: How a Hashtag Became a Rallying Cry Against Sexual Harassment’, The Guardian, 21 October 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/20/women-worldwide-use-hashtag-metoo-against-sexual-harassment>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 3 | See SEED Workshops website, <www.seedworkshops.com.au>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 4 | Locker Room can be viewed on Nash’s website; see <http://www.gretanash.com/locker-room>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 5 | See ‘Report Abuse’, Office of the eSafety Commissioner website, <http://esafety.gov.au/complaints-and-reporting>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 6 | Elle Hunt, ‘“20 Minutes of Action”: Father Defends Stanford Student Son Convicted of Sexual Assault’, The Guardian, 6 June 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/jun/06/father-stanford-university-student-brock-turner-sexual-assault-statement>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 7 | Tara Culp-Ressler, ‘Four Adults Charged with Helping Cover Up the Steubenville Rape Case’, Think Progress, 25 November 2013, <https://archive.thinkprogress.org/four-adults-charged-with-helping-cover-up-the-steubenville-rape-case-ff77291aeb5a/>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 8 | ‘One in Five Australians Is a Victim of “Revenge Porn”, Despite New Laws to Prevent It’, media release, RMIT University, 23 July 2019, <https://www.rmit.edu.au/news/all-news/2019/jul/revenge-porn-laws>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 9 | See ‘What’s the Law in My State or Territory?’, Office of the eSafety Commissioner website, <https://www.esafety.gov.au/key-issues/image-based-abuse/legal-assistance/law-in-my-state-territory>, accessed 4 November 2020. |

| 10 | See Matilda Boseley, ‘Revenge Porn in Australia: The Law Is Only As Effective as the Law Enforcement’, The Guardian, 9 May 2020, <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/may/09/revenge-porn-in-australia-the-law-is-only-as-effective-as-the-law-enforcement>, accessed 4 November 2020. |