GIRL: You must look after your blazer. It’s got to last! We don’t want people thinking we’re a couple of tramps.

WHITE BOY: What people?

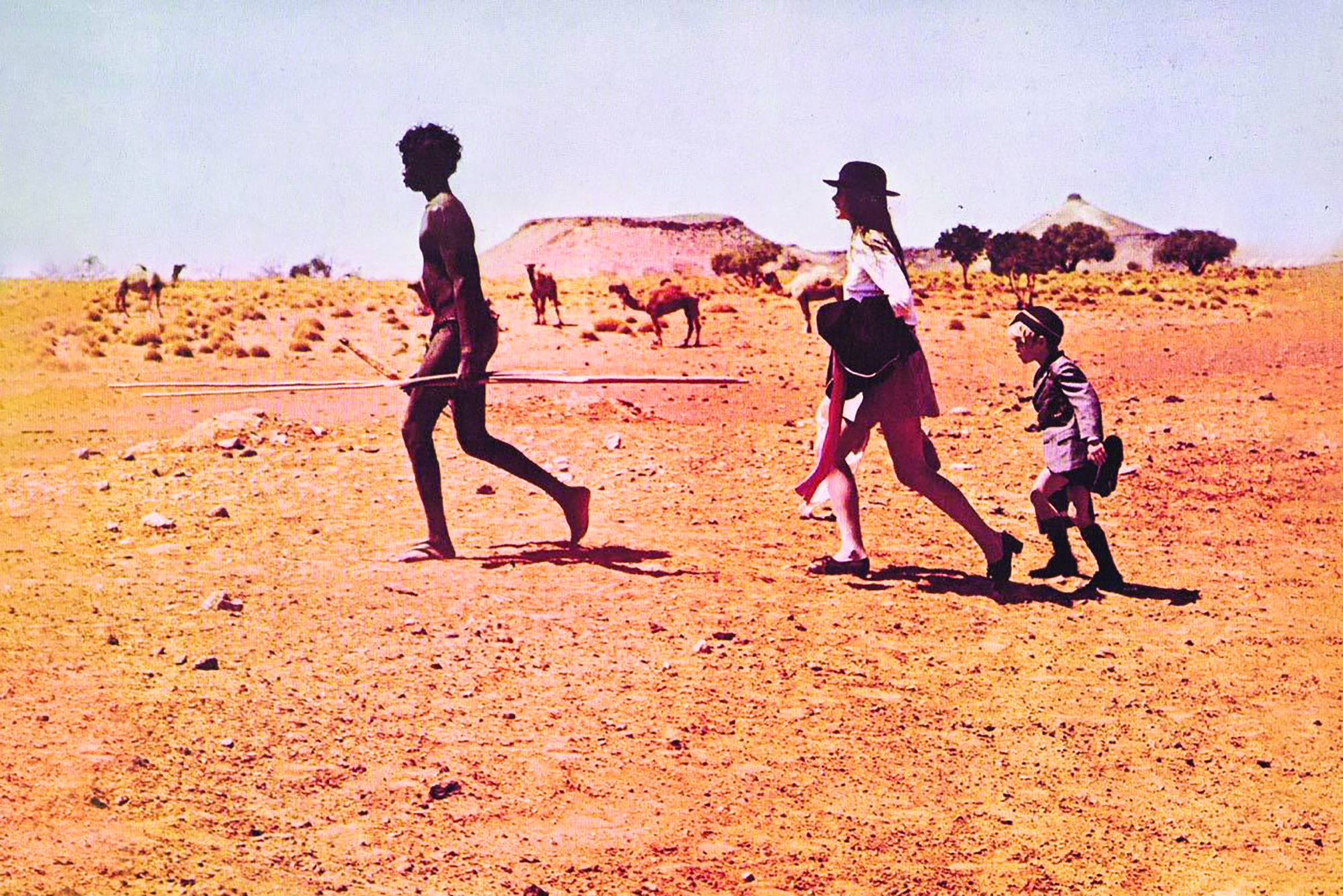

Walkabout (Nicolas Roeg, 1971) occupies an unusual space in Australian cinema. In several key respects, it is not an Australian film at all: its key producers were American; much of its crew was British; and it was designated a UK entry at the 1971 Cannes Film Festival, where it premiered. Yet the film’s overwhelming sense of place gives it the look of an Australian film, particularly as the landscape is not simply a backdrop but a dominating force in the unfolding drama.

Although Walkabout preceded the zenith of the Australian film revival by several years, it already anticipated some of its key features. Whether it was formally influenced by Roeg’s film or not, Picnic at Hanging Rock (Peter Weir, 1975) seems a close relative in terms of style and content, with its arthouse ambience of enigma, its evocation of burgeoning female sexuality, its background of school uniformity and, above all, a picnic – which in both films leads into mystery and dread. Similarly related is the following year’s Storm Boy (Henri Safran, 1976), a more popular and accessible film than Walkabout that nevertheless shares some of its themes (the relationship between humankind and nature), character archetypes (the Aboriginal figure who acts as guide and mentor, in each case played by David Gulpilil) and events (the invasion of the hunters).

Translated images

Walkabout is based on a 1959 novel by Donald G Payne (writing under the pseudonym James Vance Marshall), The Children, in which a teenage girl and her younger brother are left stranded in the Australian outback and encounter an Aboriginal boy in the midst of a solitary initiation ritual. Roeg had originally intended to make this his debut film as director; but, because of the delay in raising the necessary finance, instead took the opportunity to co-direct Performance (1970) with Donald Cammell in the meantime. One consequence of the delay was that, by the time they were ready to shoot, Roeg’s original choice for the boy – his son Nico – was too old to play the part, which instead went to Nico’s younger brother Luc (billed in the film as Lucien John).

Although the core of the novel remains intact, the film makes several adjustments, some minor and some more significant. In the novel, the white children are American and called Mary and Peter, whereas in the film they are British and remain unnamed. More conspicuously, the change of title from The Children to Walkabout shifts the focus of the story onto the Aboriginal character: after all, would the white children have survived without him? Or, to pose the question another way, would he have survived if he had not encountered them?

One remarkable characteristic of the film is the complete absence of any of the conventions typically associated with this kind of ‘lost children’ narrative: that is, there are no scenes of search, rescue, reunion or reconciliation.

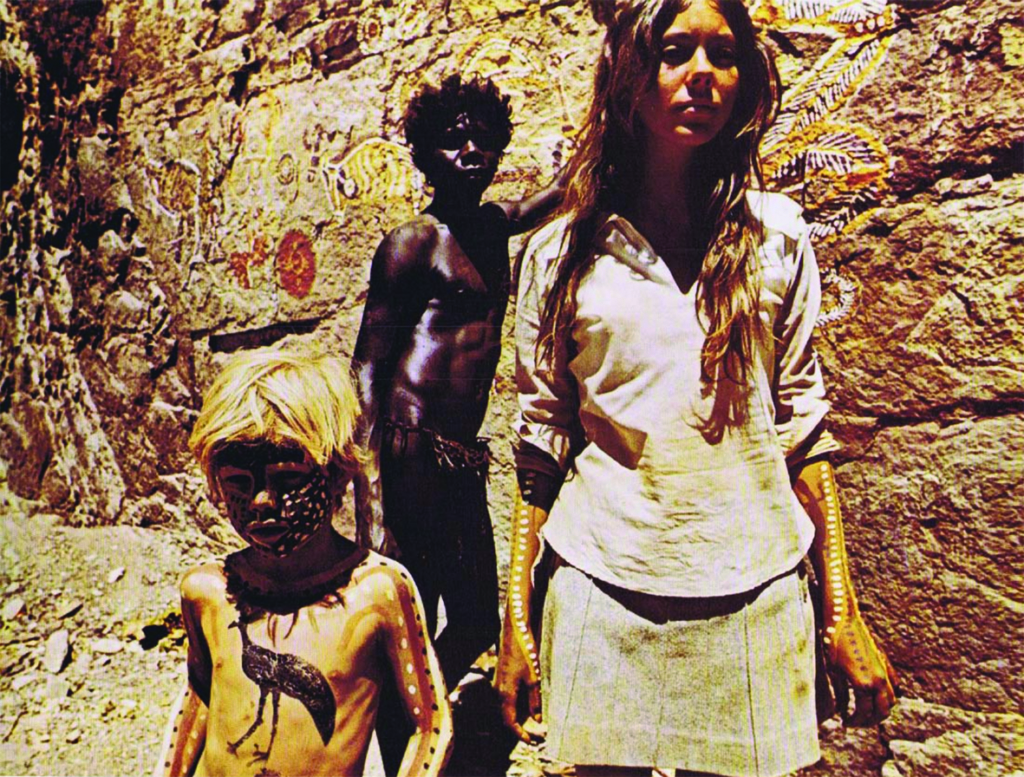

In her introduction to the 2009 reprint of the novel, Julia Eccleshare states that ‘at its heart this is a story of survival’,[1]Julia Eccleshare, ‘Introduction’, in James Vance Marshall, Walkabout, Puffin Books, 2009, p. x. but, for Roeg, the film was equally a story of identity.[2]See Gordon Gow, ‘Identity’, Films and Filming, vol. 18, no. 4,January 1972, pp. 18–24. The children’s school uniforms are an important aspect of this: they represent an identity society has already placed upon them – one which, over the course of their journey, they begin to shed. One remarkable characteristic of the film is the complete absence of any of the conventions typically associated with this kind of ‘lost children’ narrative: that is, there are no scenes of search, rescue, reunion or reconciliation. During their time in the wilderness, they seem to have stepped onto another planet.

One of the major differences between novel and film is the event that leads to the children being stranded in the desert in the first place. In the novel, it is a plane crash that has left them as the sole survivors. In the film, their abandonment is even more traumatic: they are left there by their father, who tries to kill them and then turns his gun on himself, not before having set fire to his car in a conscious endeavour to minimise their chance of survival.

Out of balance

In story terms, the opening could hardly be more benign. Father (John Meillon) returns home after a day at the office; mother (Hilary Bamberger) prepares the evening meal while listening to a recipe on the radio; a teenage girl (Jenny Agutter) and her younger brother come home from their respective schools and swim in the family pool. Yet the film conveys these events in an oblique and unsettling way, with a concatenation of sound and image edited to suggest collision more than connection. Over the soundtrack there are blasts of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s ‘Hymnen’, sounds of marching feet and schoolgirls’ breathing exercises. The sound of a didgeridoo throbs uneasily under these images, suggesting the presence of an ancient land and culture lurking underneath all the twentieth-century urban construction.

Shots of regimented commuters marching to work call to mind lines from TS Eliot’s The Waste Land about the ‘Unreal City’ where ‘each man fixed his eyes before his feet’.[3]TS Eliot, The Waste Land, W. W. Norton and Company, New York & London, 2001 [1922], p. 7. There is no sense of intimacy or communication; barely any words are spoken. Visually and aurally, the opening sequence offers a disturbing evocation of the pressures of modern life and the familiarity of a family routine that is hardening into alienation. On two occasions, the camera pans right from a solid brick wall: the first time to reveal the city; the second, to reveal a desert.

When the film returns to the desert landscape, a car has stopped there – not for the first time, apparently. The occasion is a picnic, but the atmosphere is anything but relaxed. Inside the car, the father is reading some typewritten reports about mineral holdings, pausing only to reprimand his son for speaking with his mouth full and to switch off the radio that his daughter has been enjoying. The familial set-up looks odd for an outing: Where is the mother? Why are the children still in their school uniforms?

The girl gets out of the car to lay the cloth for the picnic and her brother plays first with a toy car and then with his toy gun, but he is startled when a real shot rings out, hitting a rock close to where is standing. As the children take cover, the father’s voice is heard, his words alternating between harsh warnings and banal, self-directed musings related to business. Then a fire blazes from the car, and another shot resounds. The girl does not need to look back to know what has happened. The children must now move quickly from the unknowable (the motivation behind their father’s actions) into the unknown (the challenge of the desert).

Strangers

‘We’re lost, aren’t we?’ says the boy, with the directness of childhood. ‘No, of course not,’ replies the girl, with the evasiveness of budding adulthood. Overnight, a providential waterhole has dried up, leaving them to seek shade under the branches of a nearby quandong tree.

In the novel, the Aboriginal boy appears behind the children suddenly. In the film, his first appearance is more mysterious, dramatic and active, for he is in the process of tracking an animal for meat. But how to communicate? The girl – the older, more sophisticated of the siblings – tries language, failing miserably: ‘We’re English. English. Do you understand? […] Where is Adelaide?’ Her brother, on the other hand, is more down-to-earth and direct. Exasperated by his sister’s grown-up inclination to think ahead rather than attend to immediate concerns, he says, ‘Ask him for water!’ and then mimes the action of drinking. The Aboriginal boy understands instantly; an instinctive, non-verbal form of communication through gesture succeeds where words have failed. This sets a pattern for future interactions between the three, wherein the white boy communicates with this stranger more easily than the girl does. The Aboriginal boy will lead them to safety; they will lead him to his death.

The reason for each death remains oblique, but one can infer that they are complementary: each life in a very different way a casualty of the urbanised, mechanised world.

During their journey, as the white children rediscover the delights of climbing a tree, Roeg intercuts their game with shots of Aboriginal people who have found and are now exploring the father’s burnt-out car. Two different games are strangely linked by the fate of a burnt-out executive, now no more than a charred corpse propped up against a tree. Later, the girl luxuriates in a naked swim in a lake (the visual inspiration seems to be Sidney Nolan’s famous painting Woman and Billabong), a sequence that is cross-cut with a contrasting scene at an isolated weather station where the inhabitants are bored and incommunicative. Later still, a white woman passes the Aboriginal boy, suggesting the three are closer to civilisation than they realise; yet she is so preoccupied with her own situation that the strangeness of what she sees (an Aboriginal boy with two white schoolchildren in the back of beyond) fails to stir her curiosity, and she wanders back into her own environment, indifferent to the children’s fate.

The siblings’ separation from this world is short-lived. The Aboriginal boy soon discovers a road, a point of departure that signals their contrasting destinies: the white children’s return to their ordinary lives, and, for their guide, death by his own hand. After lying among the skeletons of dead animals – beasts gunned down by hunters who kill for profit rather than survival – the Aboriginal boy performs a mating dance before the girl. He does so, it seems, to invite her to join his world, but she is already in retreat, and her rejection turns the performance into a dance of death; thus the film is bookended by suicides. The reason for each death remains oblique, but one can infer that they are complementary: each life in a very different way a casualty of the urbanised, mechanised world.

Reminiscence

The ending of the film differs markedly from the novel as well as from the first draft of the screenplay.[4]Daniel Bird clarifies these differences as such: ‘The source novel ends with the girl overcoming racist fears and shameful feelings towards her own nudity. In Roeg and Bond’s treatment, the enemy is colonialism and capitalism. The ending of the screenplay clarifies that the boy and girl’s father was an employee of the London-based mining corporation that had plundered Aboriginal land, leaving a ghost town in its wake.’ Bird, supplementary booklet, Walkabout, Second Sight, special edition Blu-ray, 2020. Unexpectedly, it jumps forward several years. The girl is now a young woman, cutting meat in preparation for her husband’s return from work, as her mother was doing in the same apartment in the film’s opening sequence. Her husband’s (John Illingsworth) arrival likewise visually – and, perhaps, ominously – mimics that of her father at the beginning. As he talks excitedly about his imminent promotion in the competitive world he inhabits (‘Old Mal looks like being out of a job; still, it’s his own fault’), she is only half listening, and the sound dips as her mind drifts back to an image of herself, her brother and the Aboriginal boy together, naked, sunbathing by the lake, with their school uniforms staked out on sticks like scarecrows. Over the soundtrack, a narrator speaks some lines from the fortieth poem in AE Housman’s 1896 collection A Shropshire Lad:

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

There is a big difference, of course, between Housman’s Shropshire and the Australian outback – but it is the sentiment that Roeg is after, not the setting. The lines clearly meant a lot to him; he went to some lengths to ensure he had copyright approval to quote them in the film, and he quotes them in his autobiography when reflecting on his disappointment at being replaced as director of photography on David Lean’s Doctor Zhivago (1965).[5]Nicolas Roeg, The World Is Ever Changing, Faber & Faber, London, 2013, pp. 135–9. In this context, the lines express acceptance as much as regret; in Walkabout, the girl might have slipped back into her familiar city life, but her reminiscence signals that her experience in the desert still lives on in her mind: as a lingering doubt about the road not taken, perhaps.

Seeing with new eyes

In a review of Walkabout upon its original release in the UK in 1971, the great Australian critic Gordon Gow concluded, ‘If [the film] sends thoroughgoing materialists away enraged but thinking deep, this could be a film that plays its little part in changing the ways of the world.’[6]Gordon Gow, Walkabout review, Films and Filming, vol. 18, no. 3,December 1971, p. 54. Fifty years on, that response looks remarkably prescient. Viewed today, one is struck as much by the starkly unflattering picture Walkabout presents of modern humanity as by its pictorial power. There is not one sympathetic adult character in the entire film. The first buildings the children see on their re-entry to so-called civilisation (the shed, the disused mine) are hideous – ‘This is all private property […] don’t touch anything,’ an employee tells them – and the city to which they return can, as they have already seen, drive a man mad.

Yet, although the film’s landscape is Australian, the themes are universal. In view of recent global events, might not this be an ideal time, fifty years after Walkabout’s release, to re-evaluate humanity’s relationship with the environment and the natural world? After the seismic upheavals of the past year or so, will we just slip back unthinkingly into our old routines and values? The ending of Walkabout suggests that the girl might still be aware of alternative possibilities, a simpler form of existence, a reassessment of priorities. Is a return to ‘normality’ the best humanity is capable of? These are the questions the film now poses, and they could hardly be more urgent.

Endnotes

| 1 | Julia Eccleshare, ‘Introduction’, in James Vance Marshall, Walkabout, Puffin Books, 2009, p. x. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Gordon Gow, ‘Identity’, Films and Filming, vol. 18, no. 4,January 1972, pp. 18–24. |

| 3 | TS Eliot, The Waste Land, W. W. Norton and Company, New York & London, 2001 [1922], p. 7. |

| 4 | Daniel Bird clarifies these differences as such: ‘The source novel ends with the girl overcoming racist fears and shameful feelings towards her own nudity. In Roeg and Bond’s treatment, the enemy is colonialism and capitalism. The ending of the screenplay clarifies that the boy and girl’s father was an employee of the London-based mining corporation that had plundered Aboriginal land, leaving a ghost town in its wake.’ Bird, supplementary booklet, Walkabout, Second Sight, special edition Blu-ray, 2020. |

| 5 | Nicolas Roeg, The World Is Ever Changing, Faber & Faber, London, 2013, pp. 135–9. |

| 6 | Gordon Gow, Walkabout review, Films and Filming, vol. 18, no. 3,December 1971, p. 54. |