In the years since his internationally successful feature debut, Samson & Delilah (2009), Warwick Thornton has not been unproductive. He has made documentaries, written other films, and produced art and video installations, including the immersive Mother Courage; as Thornton has explained in an earlier issue of Metro, ‘Not all stories are feature films.’[1]Warwick Thornton, quoted in Thomas Redwood, ‘Skeletons in the Nation’s Cupboard: Warwick Thornton on Being an Aboriginal Artist’, Metro, no. 181, Winter 2014, p. 86. Yet his fiction features – especially his more recent, Sweet Country (2017) – can be considered key pieces in his catalogue of art. While many things make his oeuvre significant, it is particularly noteworthy for its affective sound design, which is both specific in the context of Australian cinema and striking for the way it encourages the audience to participate. As academic Isabelle Delmotte has written, ‘To an audience, cinema sound designers are the mediators of a phenomenological world of sounds and silences that is in constant mutation.’[2]Isabelle Delmotte, ‘Environmental Silence and Its Renditions in a Movie Soundtrack’, Australasian Journal of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, vol. 1, 2011/2012, p. 58. This ‘mediation’ is something that Thornton, along with his teams of sound personnel, manages to achieve in his work through a careful consideration of the sensorial impact of sound, silence, dialogue and music, in concert with the moving image.

Samson & Delilah, like many films, begins aurally, before its first images appear. As white text materialises on a black screen, sounds paint a vivid picture of the setting, including dog barks and bird calls, a telephone bell and wind moving through the landscape. As soon as the credits cut to the opening image, Charley Pride’s 1972 country hit ‘Sunshiny Day’ plays over diegetic silence as a boy wakes up, inhales fumes from a tin of paint and approaches two men playing instruments, their music inaudible. When the boy picks up an electric guitar and interrupts with a tuneless screech, Pride’s music is cut and the diegetic music – soft reggae – comes up to full volume. This sonic fluidity destabilises our perspective as participants in the film world. From the very beginning, sound in Samson & Delilah is signified as something that is tied to multiple perspectives within any scene; rather than something to be trusted, it is something to be interrogated. This effect makes the soundscape unreliable and, in shifting our orientation via sonic properties, contributes to the affective power of Thornton’s storytelling.

The soundscape here is a fluid, participatory experience that conveys both physical presence and psychological desire – at varying times, we are placed in the aural perspective of an observing audience; of the boy, Samson (Rowan McNamara); or of Delilah (Marissa Gibson). The artefacts of recorded sound – radios and cassette tapes – are present in Samson & Delilah, too, much like they are in Thornton’s short film Green Bush (2005), set inside a radio station.[3]The announcer Kenny (David Page) in Green Bush – who reads, ‘You’re listening to Country Radio, Aboriginal radio in Aboriginal country’ – is heard when Samson listens to Green Bush Radio in Samson & Delilah. Following the feature’s opening sequence, Samson switches on his radio, and its commentary is softened by his covering his ears with his hands. Later, in a particularly beautiful scene, Samson brings the portable radio outside and dances under harsh, artificial light in the night air. Delilah, listening to a cassette in the car, is interrupted by the sound of Samson’s rock music interfering with her own. After a few moments of aural chaos, Ana Gabriel’s ‘¿Cómo Olvidar?’ wins out on the soundtrack and Samson, initially dancing to one thing, now seems to be dancing to another; the movement of his body takes on another resonance. When his brother (played by Matthew Gibson) approaches and turns off his radio, all the music stops.

This confusion of sonic sources, blended together in rhythm without a consistent or obvious link to the diegetic world, creates a disorienting experience for viewers that is uniquely tied to its two protagonists. As we watch Samson from Delilah’s perspective, the sound design morphs into a frame of perspectival hearing, a device for psychological and emotional communication.

Sound in Samson & Delilah and Sweet Country muddies spatial and temporal transitions, and builds on the complicated structure of Thornton’s storytelling by embedding resonances of both past and future into the narrative present.

This aural device is similarly utilised at various points in Sweet Country, particularly when characters are struggling in their plight within the landscape. For instance, when an isolated Sergeant Fletcher (Bryan Brown) looks up at the sky, searching for some relief from the vast unknown of salt flats ahead, the gentle soundscape becomes a vacuum of environmental tone – perhaps communicating shock and fear at what lies ahead. This is followed only by the character’s short, heavy breaths, conveying his anxieties about being unfamiliar with the land. Here, once again, Thornton demonstrates the importance of sound in aligning an audience with a film’s characters.

In an essay about Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Johnny Milner writes of how Peter Weir has used sound ‘to smooth visual transitions, and bridge shifts in time and space’.[4]Johnny Milner, ‘Sounding “Unstable Terrain” in Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, p. 87. In Thornton’s two features, however, aural elements do not operate in this way. Instead, sound in Samson & Delilah and Sweet Country muddies spatial and temporal transitions, and builds on the complicated structure of Thornton’s storytelling by embedding resonances of both past and future into the narrative present. His films embody what accomplished composer and sound scholar David Toop has identified as ‘[o]ne of the most compelling aspects of hearing sound’: ‘the tension between its simultaneous attributes of specificity and generality’.[5]David Toop, Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener, Continuum, New York & London, 2010, p. 49.

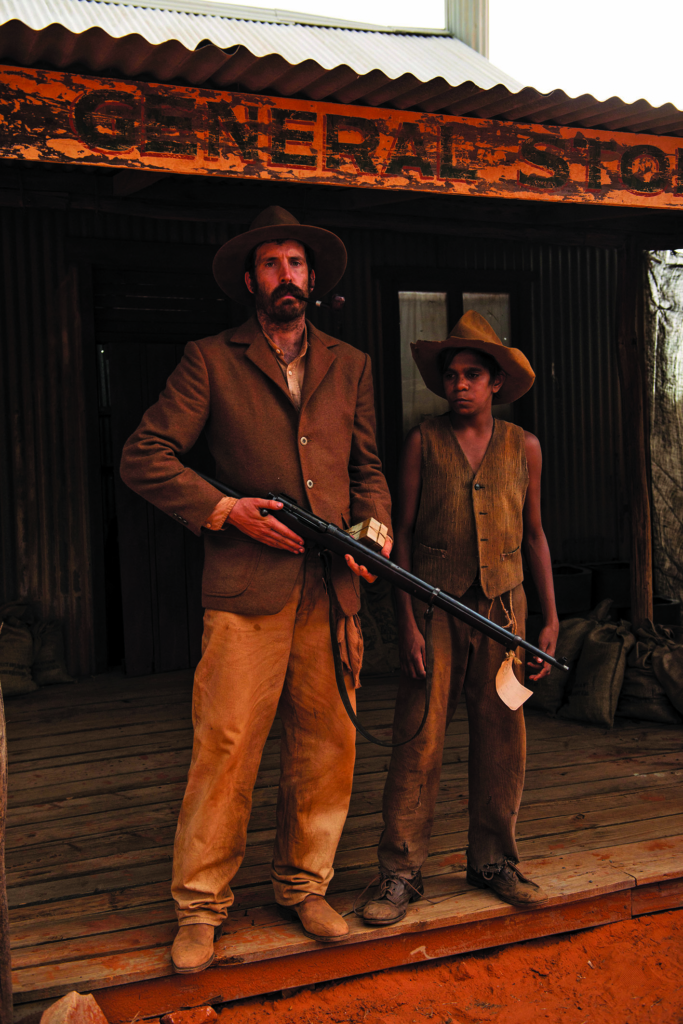

Sweet Country, especially, is filled with moments enriched by this tension, which emphasises the unsettling role of sound effects in cinema. An early example can be seen in the transition between the film’s second and third shots: a tight close-up shows Sam Kelly (Hamilton Morris) physically restrained by a clamp chained around his neck, looking straight ahead at the camera, before cutting to a wider shot of a horse cantering across a landscape. Accompanying the cut is the sound of a horse racing through dust and air – but, unsettlingly, it could also be the sound of a man falling from the gallows. With this sonic message, Thornton is already communicating his main character’s doomed ending, and the film has hardly even begun.

It is no surprise that, having been co-written by Samson & Delilah sound recordist David Tranter, Sweet Country has a detailed, affective soundscape. Haunted by its opening, the latter film pushes its narrative of postcolonial brutality forward with visuals of physical force standing out against strikingly beautiful landscape shots. Yet this is not a film that shies away from aural brutality; its most significant portrayal of violence can be found in the soundscape. During a scene that takes place in a darkened room, sound effects have a unique dramatic weight: without visual phenomena towards which to direct our attention and through which to understand what is taking place, we are made to feel vulnerable. What occurs in that scene is brutal for onscreen victim Lizzie (Natassia Gorey-Furber), but, unable to rely on our most dominant sense – sight – the audience experiences this brutality as well.

Significantly, both of Thornton’s fiction features also privilege the power of ambient sound over the power of the voice. Human listening – and, thus, much cinema – is primarily vococentric,[6]Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1999, pp. 5–6. and dialogue is often privileged above sound effects and music levels in classical filmmaking.[7]See Mary Ann Doane, ‘Ideology and the Practice of Sound Editing and Mixing’, in Teresa de Lauretis & Stephen Heath (eds), The Cinematic Apparatus, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1980, p. 52; and James Lastra, Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity, Columbia University Press, New York, 2000, p. 187. Yet, in Samson & Delilah, Samson’s voice is heard very sparingly – once to affirm his enthusiasm for music (a single ‘yeah’) and once to show his great difficulty in speaking his own name. In Sweet Country, after an initial verbal assault heard off screen (‘What are you fuckin’ doing?’), dialogue becomes de-emphasised. Sam speaks little, as do his wife and his niece, Lucy (Shanika Cole); they are victims, dispossessed of their land and their voices. Philomac (Tremayne and Trevon Doolan), the Indigenous son of white landowner Mick (Thomas M Wright), also speaks infrequently, except when in service to his father – ‘yes, boss’ is his most common retort. Otherwise, Philomac is often accompanied by the sound of chains, the materials of his imprisonment literally hanging from his body. Analysing Tracey Moffatt’s Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1990), E Ann Kaplan refers to the idea that ‘silence – choosing not to speak – befits trauma’;[8]E Ann Kaplan, Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2005, p. 133. indeed, the relative silence of the Indigenous characters in these two Thornton films encapsulates the trauma and oppression dramatised in their narratives.

In contrast, the voice of the white Australian features heavily in Sweet Country – apart from the dialogue spoken by the white characters, it is layered within sequences to allude to the complexity of the titular term ‘country’. During Harry March’s (Ewen Leslie) funeral, Laurence Binyon’s poem ‘For the Fallen’ is recited, bestowing on Harry the same honour as a soldier fallen during World War I. In the context of Sweet Country, the poem highlights the cruel duality of Harry having fought for Australia on foreign soil while having no respect for the history of Australia’s own land, specifically that of its first peoples.[9]In Thornton’s documentary We Don’t Need a Map (2017), Aboriginal writer and academic Romaine Moreton describes the imposed hierarchy under the monoculture of British colonialism in Australia as having ‘the white-bodied male at the top, and down the bottom, of course, were Aboriginal people. And then below us is country, and animals, fauna, flora. But that is a monoculture that does not see the land as a sentient being.’ When Sweet Country’s Fletcher claims, ‘Some sweet country out there,’ the comment’s irony is that, as a white man, he is part of a culture that didn’t – and doesn’t – respect the land at all. By commemorating the racist Harry in this way, the poem’s words effectively silence Australia’s first peoples, both in action and from the film’s soundtrack. It is a powerful application of both sound and language that holds great meaning for a postcolonial audience.

Elsewhere, Milner suggests that silence is a key part of white Australian history, given that the outback ‘was a bleak, eerie and dislocating place full of unfamiliar sounds’ that gave it an atmosphere of unsettling relative silence.[10]Johnny Milner, ‘Australian Gothic Soundscapes: The Proposition’, Media International Australia, no. 148, August 2013, p. 97. This sense of silence was linked to the ‘terra nullius’ falsehood – that is, to the settler experience, not that of the Indigenous Australians who have long inhabited the country. But Thornton’s films, which create vivid soundscapes from such ‘unfamiliar’ sounds and reflect on ideas relating to listening and hearing, shift beyond a conception of the Australian landscape as sonically unsettling. In this way, they build on the work of other Indigenous filmmakers, particularly Moffatt. In Night Cries, she places emphasis on the sounds of environmental and spatial isolation. In beDevil (1993), the sound of clinking chains and an aggressive voice intrude on the story of a haunted swamp; it is, according to theorists Ken Gelder and Jane M Jacobs, a ‘rare moment […] when there is actually an affective connection back to colonialism and colonial trauma’.[11]Ken Gelder & Jane M Jacobs, Uncanny Australia: Sacredness and Identity in a Postcolonial Nation, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1998, p. 39.

Thornton demonstrates that it is possible to represent the Australian country and its inhabitants without resorting to terrifying sound effects classically associated with isolation. Samson & Delilah ends almost as a fantasy, with a radio announcer dedicating a song to Samson from his absent father, before the radio station broadcasts Pride’s ‘All I Have to Offer You (Is Me)’ – a song that becomes extradiegetic as the credits begin to roll. It is a conscious mirroring of the film’s opening, which features the same artist and style of music. Sweet Country, in turn, challenges this approach. Its opening depicts violence off screen, communicated aurally, but its conclusion does not keep distance from brutality. Violence, injury and grief are heard at great volume and bared in close-up. These threads, nuances and attention to detail make Thornton’s films remarkably powerful as both stories and experiences. Despite doing different things with the soundscape, these cinematic works remain attentive to sound’s powers of narrative suggestion and affective influence.

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/samson-&-delilah

Endnotes

| 1 | Warwick Thornton, quoted in Thomas Redwood, ‘Skeletons in the Nation’s Cupboard: Warwick Thornton on Being an Aboriginal Artist’, Metro, no. 181, Winter 2014, p. 86. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Isabelle Delmotte, ‘Environmental Silence and Its Renditions in a Movie Soundtrack’, Australasian Journal of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology, vol. 1, 2011/2012, p. 58. |

| 3 | The announcer Kenny (David Page) in Green Bush – who reads, ‘You’re listening to Country Radio, Aboriginal radio in Aboriginal country’ – is heard when Samson listens to Green Bush Radio in Samson & Delilah. |

| 4 | Johnny Milner, ‘Sounding “Unstable Terrain” in Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, p. 87. |

| 5 | David Toop, Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener, Continuum, New York & London, 2010, p. 49. |

| 6 | Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman, Columbia University Press, New York, 1999, pp. 5–6. |

| 7 | See Mary Ann Doane, ‘Ideology and the Practice of Sound Editing and Mixing’, in Teresa de Lauretis & Stephen Heath (eds), The Cinematic Apparatus, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 1980, p. 52; and James Lastra, Sound Technology and the American Cinema: Perception, Representation, Modernity, Columbia University Press, New York, 2000, p. 187. |

| 8 | E Ann Kaplan, Trauma Culture: The Politics of Terror and Loss in Media and Literature, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2005, p. 133. |

| 9 | In Thornton’s documentary We Don’t Need a Map (2017), Aboriginal writer and academic Romaine Moreton describes the imposed hierarchy under the monoculture of British colonialism in Australia as having ‘the white-bodied male at the top, and down the bottom, of course, were Aboriginal people. And then below us is country, and animals, fauna, flora. But that is a monoculture that does not see the land as a sentient being.’ When Sweet Country’s Fletcher claims, ‘Some sweet country out there,’ the comment’s irony is that, as a white man, he is part of a culture that didn’t – and doesn’t – respect the land at all. |

| 10 | Johnny Milner, ‘Australian Gothic Soundscapes: The Proposition’, Media International Australia, no. 148, August 2013, p. 97. |

| 11 | Ken Gelder & Jane M Jacobs, Uncanny Australia: Sacredness and Identity in a Postcolonial Nation, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1998, p. 39. |