Something quite extraordinary happened in the early 1970s when Tony Barber was recording the last episode of the day for his daytime quiz program Temptation for the Seven Network. As a contestant pressed the buzzer and correctly answered the question that won her the game, she slumped over the desk. From where Barber was standing, it was great television: ‘I thought: Too much excitement; she’s fainted. Quick, get her some water!’ he tells me. But, as a nurse from the audience came to assist, it became apparent that something more serious had befallen the contestant. ‘People were feeling for pulses; she was being resuscitated,’ Barber recalls. ‘The studio was cleared. It was awful.’ In retelling the story, however, Barber admits that he finds solace in the knowledge that the contestant literally died happy.

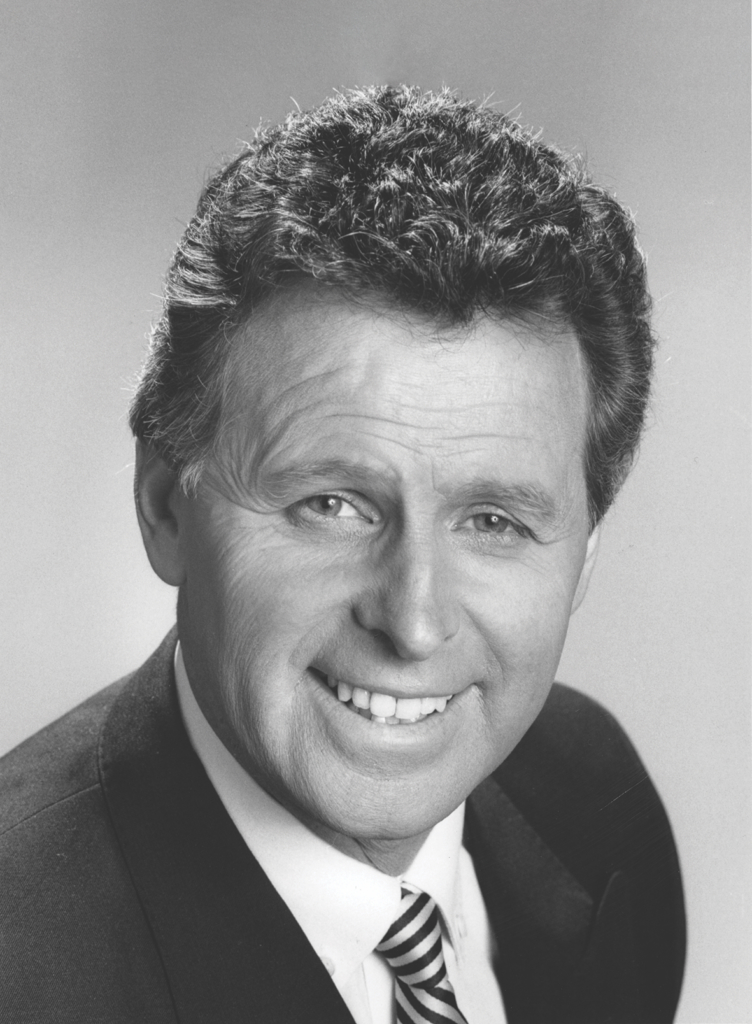

It was Bruce Gyngell – head of Seven at the time – who suggested to program packager Reg Grundy that Barber host his new game show, after seeing him in a popular television commercial for Cambridge cigarettes in the mid 1960s. The ad had Barber walking smartly down Martin Place, Sydney, whistling a jingle. Born in Lancashire, England, in 1940 and immigrating to Australia in 1947, Barber had swapped a career in the navy for one in show business, getting his start as a radio announcer in Western Australia before moving to Sydney. There, he competed in talent quests while working as an advertising executive for an agency. As he relates in his searching 2001 autobiography Who Am I?, in casting himself as the ‘Cambridge Whistler’ for the agency, he ‘suddenly had an identity in the entertainment world’: ‘Club agents who hadn’t been in the slightest bit interested in Tony Barber were now anxious to book me. I got invited onto chat shows, and was written about in the TV columns.’[1]Tony Barber, Who Am I?, Random House, Sydney, 2001, p. 93.

Barber’s contemporary Philip Brady, born in Melbourne in 1939, got his break in television much earlier: as a booth announcer at GTV-9 in April 1958. This led to live commercials and sketch work on Melbourne’s top-rated variety show In Melbourne Tonight,[2]For more on In Melbourne Tonight and Brady’s variety-show career, see Adrian Schober, ‘Welcome to Television: Philip Brady on In Melbourne Tonight and Australia’s Early Variety Shows’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 102–7. at the time headlined by Graham Kennedy. In 1960, the twenty-year-old Brady was thrilled to compere his first game show, Concentration, which went live to air on GTV-9 Melbourne on Monday afternoons. ‘It was in the days before videotape and so it was a bit scary doing a live quiz show, when things could go wrong,’ Brady reflects. ‘Because there was a puzzle board behind me, which turned like a picture board to identify various phrases and things, if the board jammed or whatever, I had to ad-lib to carry over the pregnant pause.’ While the show rated well, Grundy broke the news to Brady a year later that his local version of Concentration was going to be replaced with Grundy’s national one, to be networked out of Sydney and hosted by Terry Dear. With the advent of videotape and the Sydney–Melbourne coaxial cable, which officially opened on 9 April 1962,[3]See ‘Three Capitals Now Linked by Coaxial Cable’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1962, available at <https://www.smh.com.au/technology/from-the-archives-three-capitals-now-linked-by-coaxial-cable-20190403-p51ae2.html>, accessed 20 August 2019. all programs could be broadcast nationally.

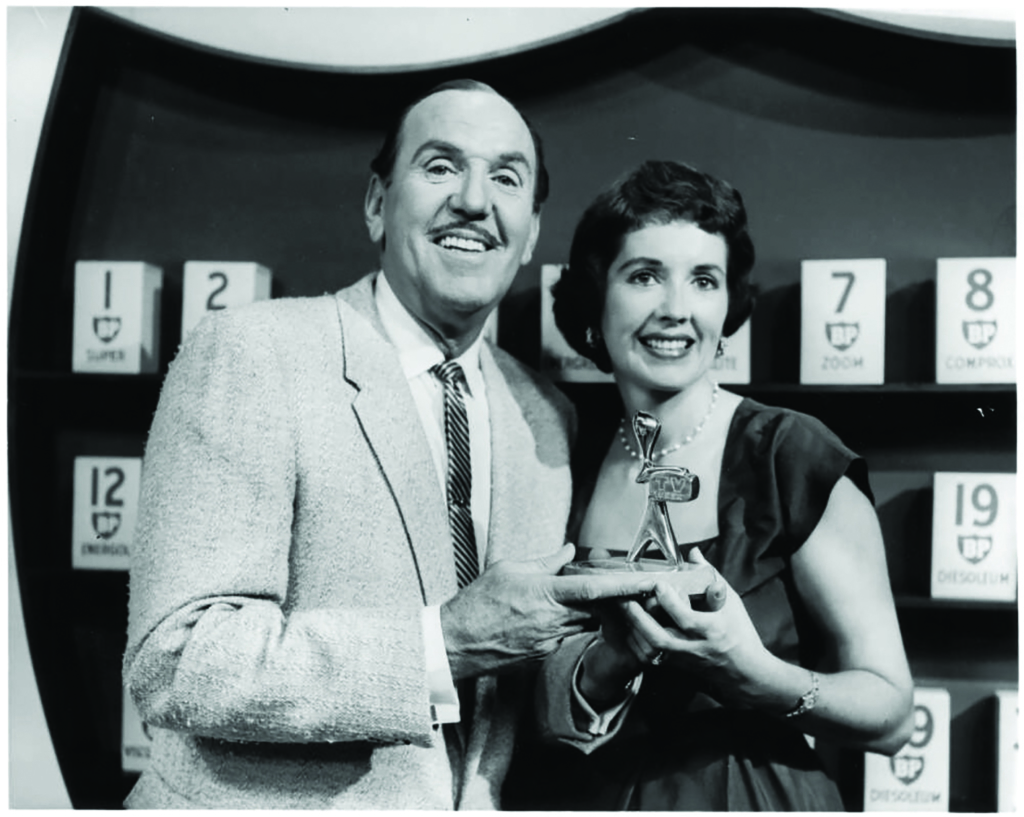

Whereas variety programs represented a convergence of radio, theatre and vaudeville, the game show was a spin-off from radio. HSV-7’s Pick-a-Box was adapted from a successful radio program, and became one of the network’s top-rated programs from 1957 to 1971. As hosted by husband-and-wife team Bob and Dolly Dyer, the show set the standard for other game shows in Australia: Dyer won a Gold Logie in 1961 for most popular television personality.[4]See Kate Matthews, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Pick a Box – Episode 170 (1963)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/pick-a-box-episode-170/notes/>, accessed 20 August 2019. One of the show’s contestants, Barry Jones – later science minister for the Hawke government – became arguably the first celebrity game-show contender on Australian television.[5]ibid. ‘I had learned the game show business by studying Pick-a-Box,’ admitted Grundy, ‘not for Bob Dyer’s performance but for the structure of the quiz elements. But it was the American game shows and their polished production techniques that really hooked me.’[6]Reg Grundy, Reg Grundy, Pier 9 Books, Sydney, 2010, p. 123. Along with variety shows, the game shows packaged by Grundy – Wheel of Fortune (unrelated to the American property he later purchased the rights for), Tic-Tac-Dough and Concentration – helped lend Australian programs a distinct place in a television schedule overrun by American and British imports.[7]Albert Moran, ‘Three Stages of Australian Television’, in John Tulloch & Graeme Turner (eds), Australian Television: Programs, Pleasures and Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989, p. 5.

Along with variety shows, the game shows packaged by Grundy – Wheel of Fortune, Tic-Tac-Dough and Concentration – helped lend Australian programs a distinct place in a television schedule overrun by American and British imports.

For the go-getting Barber, the Dyers’ exit from the game-show scene in 1971 was a godsend, for there ‘was never any question of anyone else doing their format’; as he recounted in 2001, ‘Bob owned it and, besides, it would have been unthinkable for anyone else to follow in the Dyers’ footsteps with the same show. Their link to the game was absolute.’[8]Barber, op. cit., p. 105. And so, alongside his highly successful afternoon program Temptation, the Barber-hosted Great Temptation – retitled to signal the higher stakes – was launched in July 1971 to fill the void left by Pick-a-Box in the coveted Monday 7pm slot.[9]See ‘Game Shows’, Television.AU, <https://televisionau.com/feature-articles/game-shows>; and Jamie Duncan, ‘Come on Down: Why Australians Loved Our Greatest TV Game Shows’, Herald Sun, 30 July 2018, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/come-on-down-why-australians-loved-our-greatest-tv-game-shows/news-story/9d940c68b987caacf4808f7ab603943d>, both accessed 20 August 2019.

Earlier that year, Grundy’s The Money Makers made its debut on rival channel 0/10 (the precursor to Network Ten). As hosted by Brady, the show offered one of the largest cash prizes for a game show at the time: A$20,000.[10]See ‘Ten Brisbane Turns 50’, Television.AU, 1 July 2015, <https://televisionau.com/2015/07/ten-brisbane-turns-50.html>, accessed 20 August 2019. This was first won by shy retiree Margaret Lawrence from St Kilda. ‘She made a clean sweep,’ recalls Brady. ‘She was like Barry Jones to Bob Dyer. She was invincible and knew everything.’ The show led to the spin-off Junior Money Makers in different states, which, along with the daytime programs Password, Get the Message and Casino 10, made Brady one of the busiest comperes of the 1970s. The adult edition was retitled New Money Makers to compete with Great Temptation, while Great Temptation became The $25,000 Great Temptation in 1972.[11]Albert Moran & Chris Keating, Wheel of Fortune: Australian TV Game Shows, Australian Key Centre for Cultural and Media Policy, Brisbane, 2003, pp. 76, 96, 122–3. The battle of the game shows had begun.

The Money Makers was a trailblazer in prime-time programming whose fate was bound up with Great Temptation …the 0/10 program became the first to be shown five times a week at 7pm, meaning it went head-to-head with Great Temptation on Monday nights.

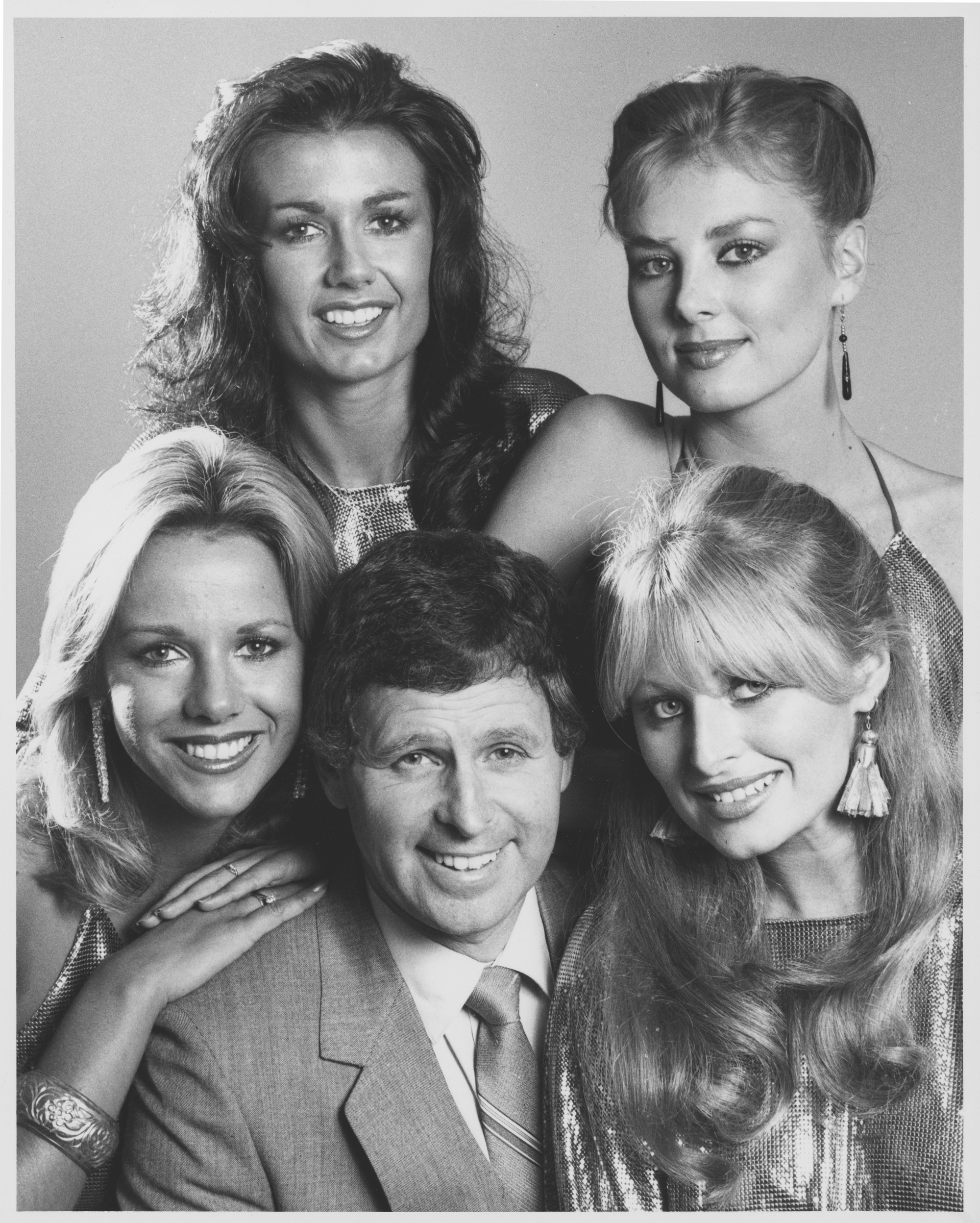

The Money Makers was a trailblazer in prime-time programming whose fate was bound up with Great Temptation. Up until then, game shows in this timeslot were shown only once a week; 7pm on Monday nights, as mentioned above, for example, were for Pick-a-Box and Great Temptation. But the 0/10 program became the first to be shown five times a week at 7pm, meaning it went head-to-head with Great Temptation on Monday nights. Grundy had learned the hard way the perils of packaging for a single network: The Money Makers rated so strongly across the week that HSV-7 also decided to have Barber’s program aired across five nights. Great Temptation’s subsequent performance, according to film and TV critic Jim Murphy, ‘was amazing, pulling ratings in the high 30s, wiping the opposition clean, winning a Gold Logie for Tony Barber’.[12]Jim Murphy, ‘Light Entertainment’, inPeter Beilby (ed.), Australian TV: The First 25 Years, Nelson & Cinema Papers, Melbourne, 1981, p. 80. Ironically, the successful stripping of Barber’s program over The Money Makers spelled the death knell for Brady’s own show in 1973. Later, when Great Temptation floundered against the cause célèbres of soap opera Number 96, HSV-7 decided to axe the game show in 1975. Yet Grundy was shrewd enough to resuscitate the format on the Nine Network as Sale of the Century, which premiered on 14 July 1980, also at 7pm. It soon became a ratings juggernaut. ‘Nothing could live with it,’ reminisces Barber. ‘You had – not just occasionally, but quite often – 50 per cent of the television sets in Australia [tuned in to the program].’ He attributes the show’s success to Nine head Kerry Packer’s brilliant exploitation of the ‘greed is good’ zeitgeist:

It was Sale of the Century on all fronts; everything was profligate. The roaring ’80s. And don’t forget that [businessman Alan] Bond owned the network for a period in the 1980s. He wasn’t averse to spending; he wasn’t going to turn around and say, ‘You’re spending too much money on this show.’

Brady with celebrity contestant Margaret Lawrence (middle) on The Money Makers

The memorable catchphrase ‘Let’s go shopping!’ – for when the big doors on stage would open to reveal the big prizes on offer – was one of Barber’s contributions to the show’s script. Barber also draws an analogy here with Australia’s national obsession: sport. ‘You got big winners, big losers, close contests,’ he muses. ‘Someone’s in front, someone comes from behind. [As compere,] you’ve got to be part–sports-show commentator; you’ve got to commentate on the game and describe what’s happening.’ Indeed, Sale produced outstanding champions like ex-boxer Cary Young and housewife Fran Powell, the latter of whom would go on to become an adjudicator for the program.[13]See Bridget McManus, ‘Back to the Future’, The Age, 29 May 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/back-to-the-future-20080529-ge74lr.html>, accessed 20 August 2019.

Whereas the early days of game shows in Australia often featured ‘older, avuncular-type comperes’ like Dyer and even Grundy himself,[14]Moran & Keating, op. cit., p. 25. their younger successors – besides Brady and Barber, there were Ernie Sigley, ‘Baby’ John Burgess and Jimmy Hannan – brought a freshness and energy hitherto unseen in the genre. Revisiting episodes of some of Brady’s old shows, I am struck by his playful repartee with contestants, perfected over years of working in variety television, and his boyish yet debonair charm (he was nicknamed ‘Dimples’), wearing a Peter Jackson suit with a cigarette in hand. Brady’s congeniality contrasts with Barber’s infectious self-confidence and near-hyperactivity; Brady calls his peer ‘the best quiz compere this country has produced. He’s quite unique.’

In that vein, I ask Barber how he came up with his signature run-up to the lectern, and he responds:

My then-producer [for Temptation] Lyle McCabe came to me and said before recording a show, ‘I’ve looked through the shows we’ve done, and what’s this sort of slow walk-on to the desk? What are you thinking about?’ I said, ‘I grew up with Bert [Newton] and that’s the way Bert does it – Bert has the languorous, slowly steady, graceful walk. I thought that was the way to do it.’ He said, ‘What about you? How do you feel about it?’ I said, ‘I am just so thrilled to have a job; I could jump from the ceiling to behind the lectern.’ He said, ‘So why don’t you do that? Just run out and give us that feeling of enthusiasm.’

Over time, Barber added other gestural elements to his high-octane performance to express his zeal: the bowler, the boxer, the kicker, the handball. And, as for the memorable send-ups of him on The Paul Hogan Show and Fast Forward, Barber considers them flattering in the extreme: ‘When someone parodies elements of your performance, it means you’re getting somewhere.’

In recent years, the tried-and-true format of the game show has come under scrutiny for its sexist aspects; as media scholar Alan McKee has argued, ‘Sale of the Century is presented by men: the hosts (Barber and [successor Glenn] Ridge). Men run the program. Men manage it. Men ask the questions. Men are in control.’ That men are hosts and women are co-hosts is, for this TV genre, a rule ‘so unbendable that the tiny number of exceptions that do exist […] appear as mutant offspring, unhealthy and doomed to die’[15]Alan McKee, Australian Television: A Genealogy of Great Moments, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001, pp. 191, 192. – consider Seven’s Now You See It (presented by Sofie Formica for two years before the show’s cancellation in 1993) and The Weakest Link (hosted by Cornelia Frances and airing for around a year in 2001–2002), while the jury is still out on the SBS reboot of Mastermind, fronted by Jennifer Byrne. Brady and Barber agree that there should be more opportunities for women as comperes. ‘In fact,’ recalls Barber,

I suggested [to the producers of Sale] that, for us to maintain our cutting edge, it would be a good idea to have alternates: say, the lady one night, and the guy another night. But you got to go back to the ‘pedigree’, and that’s how it was always done.

He also offers a more nuanced assessment of his hostesses that sees them less as ‘eye candy’ and more as performers in their own right. For example, he thinks that Barbie Rogers of Temptation / Great Temptation doesn’t get her due: ‘She wasn’t shy about saying quite extraordinary things sometimes. She put her foot in her mouth in a most entertaining way.’ Most subversive, for Barber, was the way Rogers would diss the gifts on offer to contestants, à la In Melbourne Tonight. Additionally, he points to how Sale’s Victoria Nicholls – who had acted in the Grundy soap The Restless Years in the 1970s – wasn’t ‘the “attractive model” type and broke the mould with her zany humour’. And Sale’s Alyce Platt ‘had a bit of everything: she was an actress; she was a performer. Stunningly attractive and also underrated.’

Ridge took the reins after Barber departed Sale in 1991, mainly for contractual reasons. Although it had a highly successful run that ended in 2001, the show never reached the delirious heights of its Barber days. (And the less we say of the 2005–2009 revival, the better.) In 1993, Barber had a stint compering the short-lived Ten localisation of Jeopardy!; he tells me of his disappointment in having invested so much time and energy into mounting an Australian version of a popular franchise, only to have it fail.

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, as emceed by Eddie McGuire, emerged in 1999, as Sale was nearing the end of its run. The Nine program’s current iteration, Millionaire Hot Seat, continues to attract viewers, and McGuire sees its multi-demographic appeal in egalitarian terms: ‘Because the answers are there on the screen, it means everyone can play.’[16]Eddie McGuire, in ‘Eddie McGuire Reflects on 20 Years of Millionaire Hot Seat’, 9Honey Celebrity, 1 May 2019, <https://celebrity.nine.com.au/tv/millionaire-hot-seat-20-years-how-to-win/7ea90731-6cf2-4a38-b4e7-59b525cc9bc7>, accessed 20 August 2019. Yet a case could be made that the Australian game show, as a genre, has lost much of its edge, its vitality. For Barber, Sale belongs to a golden age of commercial television, when viewers’ attention for the medium was much less divided – when a thirty-second spot on the program could launch a company’s product in a week. And, with today’s shows relying on multiple choice, lifelines and other gimmicks, winning is based less on intellect or speed and more on guesswork and chance, on the Australian tradition of ‘having a go’. As such, we’re much less likely to encounter our next Barry Jones, Margaret Lawrence, Cary Young or Fran Powell. While Barber is content in his retirement, hosting trivia nights for his local community on the Mornington Peninsula, Brady is certainly up for hosting another game show: ‘I’d love to have another crack it, absolutely. Bring back The Money Makers, bring back Casino 10.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Tony Barber, Who Am I?, Random House, Sydney, 2001, p. 93. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For more on In Melbourne Tonight and Brady’s variety-show career, see Adrian Schober, ‘Welcome to Television: Philip Brady on In Melbourne Tonight and Australia’s Early Variety Shows’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 102–7. |

| 3 | See ‘Three Capitals Now Linked by Coaxial Cable’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 April 1962, available at <https://www.smh.com.au/technology/from-the-archives-three-capitals-now-linked-by-coaxial-cable-20190403-p51ae2.html>, accessed 20 August 2019. |

| 4 | See Kate Matthews, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Pick a Box – Episode 170 (1963)’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/tv/pick-a-box-episode-170/notes/>, accessed 20 August 2019. |

| 5 | ibid. |

| 6 | Reg Grundy, Reg Grundy, Pier 9 Books, Sydney, 2010, p. 123. |

| 7 | Albert Moran, ‘Three Stages of Australian Television’, in John Tulloch & Graeme Turner (eds), Australian Television: Programs, Pleasures and Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989, p. 5. |

| 8 | Barber, op. cit., p. 105. |

| 9 | See ‘Game Shows’, Television.AU, <https://televisionau.com/feature-articles/game-shows>; and Jamie Duncan, ‘Come on Down: Why Australians Loved Our Greatest TV Game Shows’, Herald Sun, 30 July 2018, <https://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/come-on-down-why-australians-loved-our-greatest-tv-game-shows/news-story/9d940c68b987caacf4808f7ab603943d>, both accessed 20 August 2019. |

| 10 | See ‘Ten Brisbane Turns 50’, Television.AU, 1 July 2015, <https://televisionau.com/2015/07/ten-brisbane-turns-50.html>, accessed 20 August 2019. |

| 11 | Albert Moran & Chris Keating, Wheel of Fortune: Australian TV Game Shows, Australian Key Centre for Cultural and Media Policy, Brisbane, 2003, pp. 76, 96, 122–3. |

| 12 | Jim Murphy, ‘Light Entertainment’, inPeter Beilby (ed.), Australian TV: The First 25 Years, Nelson & Cinema Papers, Melbourne, 1981, p. 80. |

| 13 | See Bridget McManus, ‘Back to the Future’, The Age, 29 May 2008, <https://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/back-to-the-future-20080529-ge74lr.html>, accessed 20 August 2019. |

| 14 | Moran & Keating, op. cit., p. 25. |

| 15 | Alan McKee, Australian Television: A Genealogy of Great Moments, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001, pp. 191, 192. |

| 16 | Eddie McGuire, in ‘Eddie McGuire Reflects on 20 Years of Millionaire Hot Seat’, 9Honey Celebrity, 1 May 2019, <https://celebrity.nine.com.au/tv/millionaire-hot-seat-20-years-how-to-win/7ea90731-6cf2-4a38-b4e7-59b525cc9bc7>, accessed 20 August 2019. |