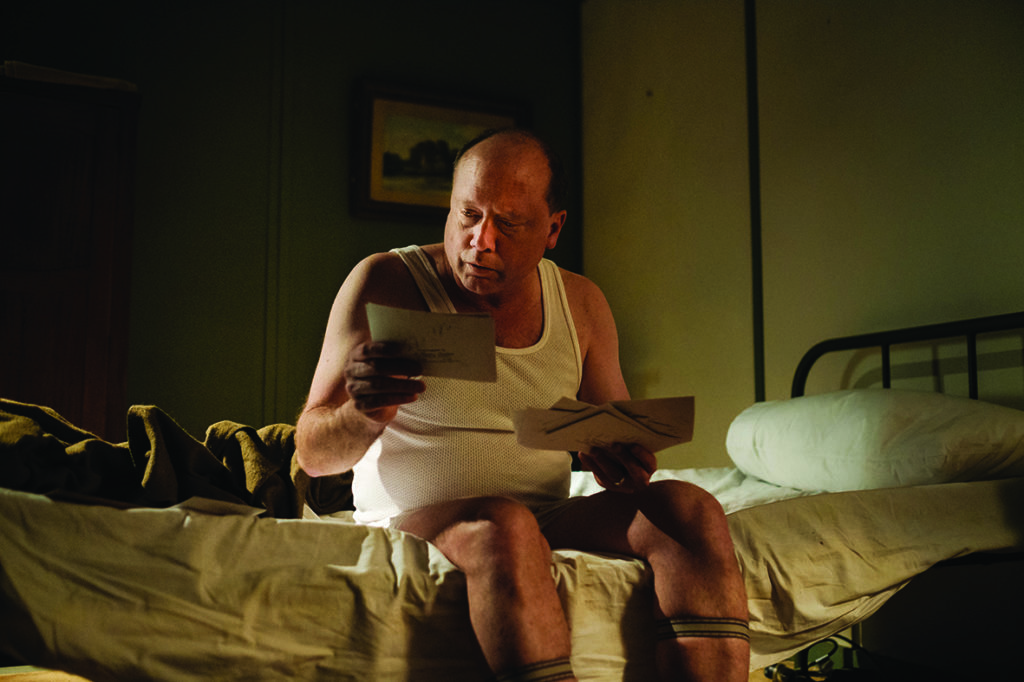

Major Leo Carmichael (Ewen Leslie) sits in a cafe in Adelaide, over 800 kilometres from the Maralinga nuclear-test site in a remote region of South Australia. At Maralinga, he is the boss, but he’s losing control: problems are spreading beyond the confines of the base as soldiers start getting sick and winds blow radiation from mushroom clouds across the state. According to the UK and Australian governments – as well as the scientists who conduct the tests for the greater good of the Commonwealth – however, what goes up in a nuclear blast comes straight down to the ground. And what’s on the ground? Nothing – or, for legal purposes, terra nullius. With all this on Carmichael’s mind, he turns to face a poster for a tobacco company with the slogan ‘will not affect your throat’, scoffs and lights a cigarette.

In Operation Buffalo, Australia is depicted as living in denial of its colonial history. The lies and cover-ups surrounding the nuclear tests are told for the sake of strengthening the British Empire in the atomic arms race, and Australia is shown to be necessarily compromised by its loyalty to the Crown.

The premise of the series is factual. After the collapse of a co-operative nuclear-research pact with the United States and Canada in the years following World War II, the UK government – with the full cooperation of then–prime minister Robert Menzies, who hoped that Britain would share its knowledge of nuclear weapons with Australia – eventually settled on Maralinga as a test site.[1]See John Keane, ‘Maralinga’s Afterlife’, The Age, 11 May 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/maralingas-afterlife-20030511-gdvoq4.html>, accessed 18 November 2020. The British would go on to detonate seven atomic bombs there between 1956 and 1963, with significant consequences: it’s estimated that 30 per cent of the British and Australian servicemen exposed to the blasts died of cancer (although the results of a royal commission in the 1980s was not conclusive on the matter). The royal commission also uncovered that the fallout of the explosions was carried much farther than the radius the British promised, and that it reached as far as Townsville, Brisbane, Sydney and Adelaide.[2]See Mike Ladd, ‘The Lesser Known History of the Maralinga Nuclear Tests – and What It’s Like to Stand at Ground Zero’, ABC News, 24 March 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-24/maralinga-nuclear-tests-ground-zero-lesser-known-history/11882608>, accessed 10 November 2020. The tests were particularly devastating for the Indigenous population, especially the Maralinga Tjarutja people, who were driven off their land by the army (as were the neighbouring Yulparitja people).[3]ibid. The Maralinga Tjarutja people would later receive only A$13 million in compensation for their displacement; while the land was eventually returned to them in 1984, the soil is said to be sterile and the community is still coming to terms with the long-term effects of radiation on its members.[4]See Ian Anderson, ‘Britain’s Dirty Deeds at Maralinga: Fresh Evidence Suggests That Britain Knew in the 1960s That Radioactivity at Its Former Nuclear Test Site in Australia Was Far Worse than First Thought. But It Did Not Tell the Australians’, New Scientist, 12 June 1993, <https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13818772-700/>; and Samantha Jonscher & Gary-Jon Lysaght, ‘Maralinga Story to Be Told Through Eyes of Traditional Owners Affected by Britain’s Atomic Bomb Testing’, ABC News, 1 July 2019, <abc.net.au/news/2019-07-01/maralinga-retelling-the-story-of-britains-atomic-bomb-testing/11249874>, both accessed 18 November 2020.

Operation Buffalo builds a story out of the sins of the British and Australian governments at Maralinga. Across its six-episode run, it’s more concerned with secrets, spies and scandals than with interrogating the situation, however. There are tonal shifts that pull a handbrake turn from, for instance, the displacement of Indigenous inhabitants to the bumbling of Australian Security Intelligence Organization agents and bureaucrats. One of the most farcical scenes in that milieu features a group of scientists trying to figure out how to blow up an undetonated warhead; the suggestion to bomb a nuclear bomb feels like it’s from a completely different show. Where the miniseries thrives is in its approach to the exploitation of the Australian people – Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike – by UK authorities.

At the mercy of the mother country

Operation Buffalo has an edge often missing from Australian-made historical dramas based on true stories. The 2015 miniseries Gallipoli looks at the sacrifices of war, but it’s more concerned with how the story plays into our national identity; while other series such as Underbelly, Howzat! Kerry Packer’s War, Beaconsfield and Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleo all take cues from real-life events but rarely interrogate their situations and subjects, instead serving as linear retellings of events with the drama dialled up.[5]For further discussion of this trend in Australian television, see Dave Crewe, ‘Crooked Histories: Underbelly and Australian Self-mythologisation’, Metro, no. 200, 2019, pp. 80–5. What these dramas have in common is their emphasis on the ‘how’ and not the ‘why’. Operation Buffalo straddles both while tapping into the discomfort of confronting the ugly things the Australian and British governments did in the name of empire.

The British Empire looms like the Union Jack on the Australian flag throughout Operation Buffalo,and is most thoroughly embodied by General Lord ‘Cranky’ Crankford (James Cromwell). An avatar for the final gasp of the Empire as it channels its paranoia into trying to harness nuclear power, Cranky is becoming senile, but rigorously adheres to outdated British traditions while recalling past glories on the battlefield. The true danger to the UK in his eyes and those of his superiors is a loss of relevancy on the world stage, and the tests at Maralinga seem like a power play to remind Australia who’s the boss.

Nuclear war is often mentioned in conversation throughout Operation Buffalo, and the tests are deemed a necessary precaution. The potential for World War III is frequently cited by the Australian soldiers to justify their actions, even though, deep down, they know they’re being exploited. The visual contrasts are everywhere on the base, most strikingly in the scenes in which the Australian soldiers clean themselves with just water and towels while the British scientists enter an enclosed building for intense decontamination. But everyone is doing their bit for the British Empire because, so the rhetoric goes, a nuclear bomb equals safety. Carmichael constantly uses the ‘necessary evil’ defence to justify the actions of his superiors, especially when he returns to Adelaide to discover a radiated weather balloon has found its way into a neighbour’s backyard.

The British say the bomb tests are a sign of progress, but what is their measure of success? A gigantic crater in the ground. There are contradictions everywhere in Operation Buffalo, but at the series’ core is an allegory for Australia’s alliance with Britain and how that relationship ends up harming the land and its people.

At the time of the nuclear tests, ‘God Save the Queen’ was still Australia’s national anthem. The divine plays a role in Operation Buffalo, too: in a moment of disorientation, Cranky hears God speak via a dying Indigenous man, and interprets the words as evidence that God is dead. If so, he surmises, then only a nuclear bomb can save the Queen.

Veracity and denial

Historical dramas are only the beginning of a conversation, and very rarely define events; rather, they tend to popularise a topic for a short period of time. Operation Buffalo fits into this category by bringing the attention of a twenty-first century audience to what happened at Maralinga.

Each episode opens with a statement: ‘This is a work of historical fiction. But a lot of the really bad history actually happened.’ The series has its guard up when it comes to any literal interpretation of the story, which brings into question the way historical dramas tend to be used as allegories rather than factual entertainment.

Operation Buffalo’s warning seems to be there to not only counterbalance the way historical dramas are interpreted but also confront Australia’s disconnect with its own history.

Written and directed by Peter Duncan, Operation Buffalo arrives within a year of HBO’s Emmy Award–winning historical drama Chernobyl, which focused on the infamous real-life nuclear disaster at the titular reactor in the Soviet Union. While television networks have not been commissioning enough nuclear-themed historical dramas to designate the shows part of any kind of trend, Operation Buffalo and Chernobyl are clear bedfellows regardless of their differences in execution – and the Australian series’ opening disclaimer can be read as a pre-emptive reaction to the way its overseas counterpart was digested.

Despite the HBO series receiving mostly positive reviews from critics, nitpicking its historical accuracy became a sport as its popularity grew.[6]For a discussion of some of these criticisms, see Garry Westmore, ‘Radioactive Material: Truth and Lies in Chernobyl’, Screen Education, no. 96, 2019, pp. 16–23. Major criticisms were aimed at Chernobyl for being too realistic, and thus increasing the chance of audiences interpreting fiction as fact. Columnist Masha Gessen made this observation in The New Yorker, referring to fictionalised sequences of scientists confronting authorities directly:

By and large, Soviet people did what they were told without being threatened with guns or any punishment […] Resignation was the defining condition of Soviet life. But resignation is a depressing and untelegenic spectacle. So the creators of Chernobyl imagine confrontation where confrontation was unthinkable – and, in doing so, they cross the line from conjuring a fiction to creating a lie.[7]Masha Gessen, ‘What HBO’s Chernobyl Got Right, and What It Got Terribly Wrong’, The New Yorker, 4 June 2019,<https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/what-hbos-chernobyl-got-right-and-what-it-got-terribly-wrong>, accessed 10 November 2020.

Writing for The Atlantic, however, Sophie Gilbert approached the series as less of a historical exposé than a riveting fable for contemporary threats:

Chernobyl is […] a warning – one that straddles the line between prescience and portentousness. Whether you apply its message to climate change, the ‘alternative facts’ administration of the current moment, or anti-vaccine screeds on Facebook, [showrunner Craig] Mazin’s moral stands: The truth will eventually come out. The question he poses, however self-consciously, is whether hundreds of thousands of lives must always be sacrificed to misinformation along the way.[8]Sophie Gilbert, ‘Chernobyl Is a Gruesome, Riveting Fable’, The Atlantic, 6 May 2019, <https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/05/chernobyl-gruesome-riveting-fable-hbo/588688/>, accessed 10 November 2020.

Operation Buffalo’s warning seems to be there to not only counterbalance the way historical dramas are interpreted but also confront Australia’s disconnect with its own history. It’s akin to the ongoing debate about moving the date of Australia Day, widely seen by the Indigenous population as a day of mourning. A paradox forms when celebration and mourning occur on the same day.

A 2019 study on attitudes towards Australia Day conducted by the Australian National University’s Social Research Centre found that 70 per cent of respondents agreed that 26 January was the best day for national celebration, while only 27 per cent disagreed. The study then asked which ‘aspects of Australia’s culture and heritage are thought to be most strongly associated with the 26 January Australia Day celebrations’: 68 per cent said it ‘celebrates our British culture and heritage’; 63 per cent said it ‘celebrates our democracy and system of government’; and 58 per cent said it ‘celebrates the contribution of all immigrants’. Only 45 per cent of respondents agreed that it ‘is offensive to Indigenous Australians’.[9]Darren Pennay & Frank Bongiorno, ‘Barbeques and Black Armbands: Australians’ Attitudes to Australia Day’, Social Research Centre website, 25 January 2019, <https://www.srcentre.com.au/bbqsandblackarmbands>, accessed 10 November 2020. These results suggest that a majority of Australians still view the country’s national day positively while associating it with our colonial past, despite all of that past’s horrors. It’s the ultimate example of Australia’s disconnect with its own history, which is the moral quandary at the core of Operation Buffalo.

In film and television, the darker truths of Australia’s colonial heritage and relationship with the UK can often be sidelined in favour of stories that prop up a sense of national identity. In Operation Buffalo’s tale of lingering radiation, those depravities cannot be so easily scrubbed away.

Endnotes

| 1 | See John Keane, ‘Maralinga’s Afterlife’, The Age, 11 May 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/national/maralingas-afterlife-20030511-gdvoq4.html>, accessed 18 November 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Mike Ladd, ‘The Lesser Known History of the Maralinga Nuclear Tests – and What It’s Like to Stand at Ground Zero’, ABC News, 24 March 2020, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-24/maralinga-nuclear-tests-ground-zero-lesser-known-history/11882608>, accessed 10 November 2020. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | See Ian Anderson, ‘Britain’s Dirty Deeds at Maralinga: Fresh Evidence Suggests That Britain Knew in the 1960s That Radioactivity at Its Former Nuclear Test Site in Australia Was Far Worse than First Thought. But It Did Not Tell the Australians’, New Scientist, 12 June 1993, <https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13818772-700/>; and Samantha Jonscher & Gary-Jon Lysaght, ‘Maralinga Story to Be Told Through Eyes of Traditional Owners Affected by Britain’s Atomic Bomb Testing’, ABC News, 1 July 2019, <abc.net.au/news/2019-07-01/maralinga-retelling-the-story-of-britains-atomic-bomb-testing/11249874>, both accessed 18 November 2020. |

| 5 | For further discussion of this trend in Australian television, see Dave Crewe, ‘Crooked Histories: Underbelly and Australian Self-mythologisation’, Metro, no. 200, 2019, pp. 80–5. |

| 6 | For a discussion of some of these criticisms, see Garry Westmore, ‘Radioactive Material: Truth and Lies in Chernobyl’, Screen Education, no. 96, 2019, pp. 16–23. |

| 7 | Masha Gessen, ‘What HBO’s Chernobyl Got Right, and What It Got Terribly Wrong’, The New Yorker, 4 June 2019,<https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/what-hbos-chernobyl-got-right-and-what-it-got-terribly-wrong>, accessed 10 November 2020. |

| 8 | Sophie Gilbert, ‘Chernobyl Is a Gruesome, Riveting Fable’, The Atlantic, 6 May 2019, <https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/05/chernobyl-gruesome-riveting-fable-hbo/588688/>, accessed 10 November 2020. |

| 9 | Darren Pennay & Frank Bongiorno, ‘Barbeques and Black Armbands: Australians’ Attitudes to Australia Day’, Social Research Centre website, 25 January 2019, <https://www.srcentre.com.au/bbqsandblackarmbands>, accessed 10 November 2020. |