On release, Sirens (John Duigan, 1994) inspired more derision than admiration. Even the more positive reviews dismissed it as a ‘soft-core, high-minded daydream’[1]Janet Maslin, ‘Naughtiness in Pooh Land’, The New York Times, 4 March 1994, Section C, p. 16, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1994/03/04/movies/review-film-naughtiness-in-pooh-land.html>, accessed 15 February 2022. or a ‘marriage between Masterpiece Theatre and Baywatch’.[2]Hal Hinson, ‘Sirens (R)’, The Washington Post, 11 March 1994, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/sirensrhinson_b009e1.htm>, accessed 18 January 2022. A recurring theme was the film’s prurience, seeming to stake its appeal on the willingness of the eponymous sirens (and most of the female cast) to strip off every couple of minutes.

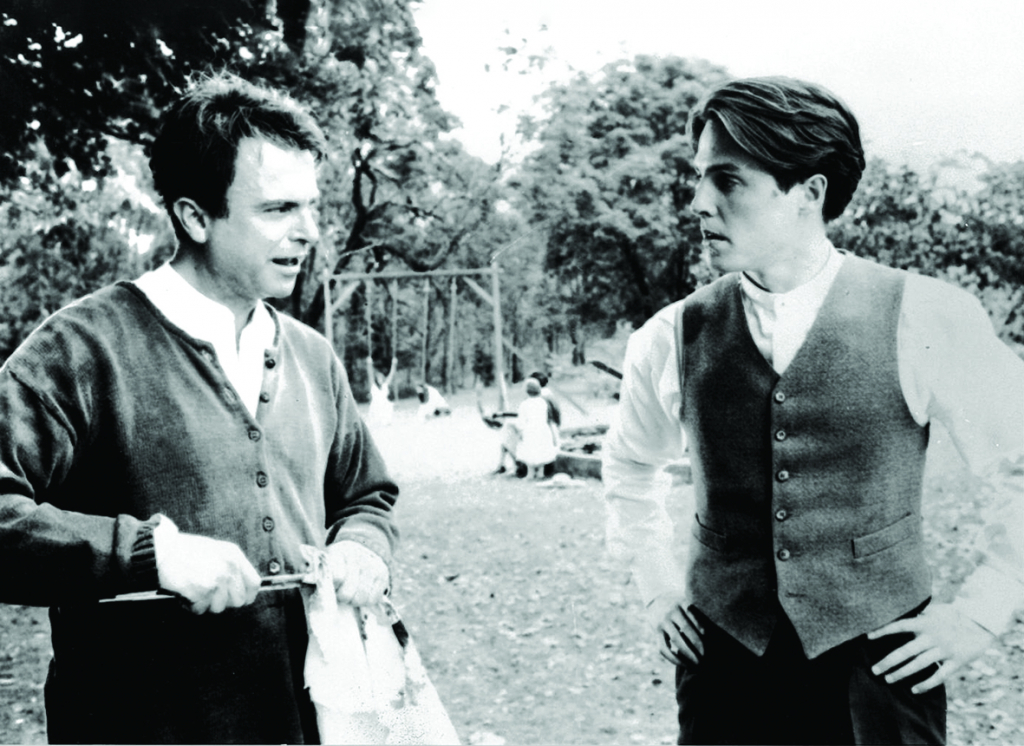

There is no getting away from director John Duigan’s self-conscious championing of the male gaze. In a featurette on the Blu-ray release, star Hugh Grant ribs Duigan on how often his scripts seem to demand female nudity ‘for artistic reasons’.[3]Hugh Grant, in the featurette Informal Home Movie Chat Between Hugh Grant and Director John Duigan, Sirens, Blu-ray, Umbrella Entertainment, 2021. But the use of that gaze in the film is more complex than its portrayal in traditional critiques, in which women are defined and shaped by the way men look at them. In using the female form – and, more importantly, oppressed female sexuality – as a crux to explore tensions between religious conservatism and art, Duigan digs into how looking changes the looker, not just the looked-at.

Set during the interwar period, Sirens concerns progressive English priest Anthony (Grant) and his wife Estella (Tara Fitzgerald) being sent to the Blue Mountains refuge of artist Norman Lindsay (Sam Neill), in the hope they can convince him to retract one of his more provocative works – a voluptuous nude on the cross – from a public exhibition. The Church cites moral outrage and blasphemy, but it’s clear the real fear is the female form and what might happen if Joe (or Josephine) Public is exposed to it.

In Duigan’s film, the real power lies with the object, not the objectifier. Female sexuality is represented as a primal force, trapped within a pressure cooker of gendered expectations, but likely to erupt at the slightest provocation. To the voyeur (male or female; there are plenty here), it brings the promise of corruption – or, perhaps, liberation.

Voyeurism and civilisation

In her seminal 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, theorist Laura Mulvey situates voyeurism within existing gendered power dynamics, describing how erotic objectification can distort how the observer thinks about men and women more generally. She argues that most American films are beholden to a heterosexual, masculine scopophilia (that is, the sexual pleasure involved in looking): woman becomes ‘spectacle’, while man becomes ‘the bearer of the look’.[4]Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, Autumn 1975, p. 12.

On the face of it, Sirens does nothing to defend itself from this analysis. The casting of supermodels Elle Macpherson and Kate Fischer as two of the ‘sirens’ – actually, life models employed by Norman – contributes to this sense of spectacle, offering the promise of boobs for a heterosexual male audience who might otherwise eschew an arthouse film. The actors are there to be stared at – or leered over – rather than appreciated for the nuance and depth they bring to their characters.

And yet Sirens argues that voyeurism is not an exclusively male predilection, but rather a human instinct: we are drawn to looking at bodies and sex, and this looking changes us; we are more sensual than many of us would like to admit; freed from social conventions or the strictures of religion, we fall victim to reckless lust. In this, the religious conservatives and bohemian artists are in agreement – where they differ is whether this is a good or bad thing.

Duigan’s position is not exactly ambiguous. Although Rose Lindsay (Pamela Rabe) describes her husband as a ‘very depraved man’, Neill’s portrayal is that of a sympathetic eccentric – a reclusive artist and intellectual who likes to surround himself with beauty, whether that be the stunning landscape of the Blue Mountains or statuesque nude women. Like Duigan’s film, Norman appears resigned to the contradictions of human nature: our simultaneous capacity for great intellectual and artistic achievement and baser primal obsessions.

Sirens argues that voyeurism is not an exclusively male predilection, but rather a human instinct: we are drawn to looking at bodies and sex, and this looking changes us; we are more sensual than many of us would like to admit.

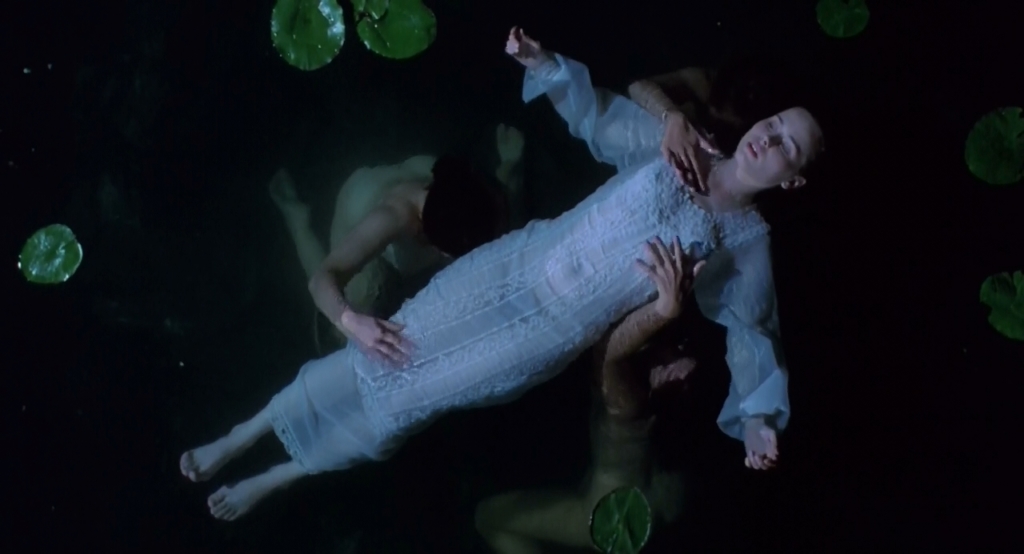

When we first meet Estella, it is in black-and-white: we see a romantic vision of sea travel, the wild oceans conquered by human ingenuity in the form of a steamship. That image of the ship returns through the film – sometimes mockingly, sometimes as a portent, with the fate of the Titanic never being far from our minds. We are reminded, often comically, that the sea is a dangerous force, full of dangerous creatures waiting to drag us down.

For Estella, the colour, chaos and rudeness of rural Australia comes as a rude shock. Although some reviews of the time described her as ‘naive’,[5]See, for example, David Stratton, ‘Sirens’, Variety, 7 March 1994, <https://variety.com/1994/film/reviews/sirens-1200436397/>, accessed 15 February 2022. she might better be called ‘unflappable’. Hers is a particular kind of Englishness, one that relies on class and education to glide above the messier parts of life – specifically, the initial attempts of the sirens and Norman to destabilise her. At first, she is horrified by the freedom the sirens feel to be naked and to (literally) wade into deeper waters. And yet, increasingly drawn to the urge to gaze, she soon becomes the film’s chief voyeur, finding herself led away from that illusion of civilisation that amounts to gliding along the surface of our instincts.

Estella’s voyeurism culminates in the moment when she sees herself stripped naked in the middle of Evensong. This turning of her gaze on herself can be interpreted in at least two ways. Firstly, the act of looking has transformed her, liberating her in unexpected and frightening ways. Secondly, this might be the ironic punishment that awaits all voyeurs: as they learn to objectify others, they ultimately objectify themselves.

Neither interpretation necessarily cancels out the other. Again, what matters is the meaning the viewer gives to this liberation or corruption. In the context of a church service, Estella’s imagined nudity is comical, but also gives the lie to her husband’s claim that the Church doesn’t find bodies sinful in themselves (even if certain images, such as Lindsay’s paintings, can be considered profane). Estella’s horror at being rendered nude reveals the body-shaming that Christianity has taught its followers – particularly women – from its inception, a lesson that is present in the religion’s own Creation narrative.

Corruption and nature

When our English visitors step off the train into rural Australia, any illusions they are in God’s country are quickly dispelled. The locals are crude and unhelpful – one of the first things anyone says to them is ‘Get fucked’ – and the place is crawling with all kinds of strange and potentially dangerous creatures. There is no taxi service, so Estella is forced into the cab of a pick-up truck between two sweaty men chomping on apples (the religious symbolism needs no unpacking) while her husband is thrown about on the back until he vomits. Away from civilised society, nature gets ugly pretty fast.

And yet, in the middle of this ugliness, Norman’s Faulconbridge retreat is cast as an almost mythical pocket of beauty. Duigan has our interlopers fall asleep on the grass like children in a fairytale, only to be woken by Norman and his entourage, who have just returned from a long walk in the wilderness. We quickly discover that the usual rules of civilisation do not apply here. The women of the household think nothing of shedding their clothes (or stealing Estella’s). Sheela (Macpherson) slouches at the dinner table, eating stilton – a very pungent English cheese – with her finger. The young children are feral, capering under tables and using very unladylike language. After dinner, they rush out into the garden to see the ‘fairies’ (actually the sirens, swinging on a jerry-rigged playground).

It’s all very seductive and whimsical, but, as with every fairytale, darkness lies beneath the magic – which is not to say that the film engages with any #MeToo-style reassessment of the power dynamic between artist and muse. Nor does it tangle with Lindsay’s views on Indigenous Australians, Jews or homosexuals, some of which are as unforgivable as they are unrepeatable, even allowing for their historical context.[6]See Joe Dolce, ‘Norman Lindsay: Eros and Obscenity’, Quadrant, 27 November 2013, <https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2013/11/eros-obscenity-norman-lindsay/>, accessed 17 January 2022. Instead, the darkness is that of our own nature when the usual rules of civilisation are suspended.

In an interview from 1965 featured on the Blu-ray release, the real Lindsay is frank about the extent to which he shunned society, preferring to live by his own rules.[7]See featurette ABC Lively Arts Interview with Norman Lindsay, Sirens, Blu-ray, Umbrella Entertainment, 2021. What is confusing for Anthony in the film is the way in which these rules alternately parallel and form distortions of those of his society. While Norman is contemptuous of Christianity (describing its proponents as ‘wowsers’ and ‘Wesleyans’), he is a firm believer in reincarnation and the historical existence of Atlantis. He too worries about moral decay, but sees art – as profane as it might be – as the solution rather than the problem. His concern is that of intellectual and artistic stagnation, as the West drifts away from a perceived Atlantean ideal.

Anthony, of course, sees life and Norman’s work through the prism of sin and corruption. He thinks he is very modern and relaxed, but is utterly repressed; through his focus on the spiritual, he has become divorced from his own physicality. His marriage to Estella is essentially platonic. They call each other ‘Pooh’ and ‘Piglet’, as if determined to nullify any potential sexual attraction and sanitise their union into a state of childhood innocence. He is likewise mystified that the sirens call the outdoor toilet the ‘thunder box’, because it would require him to face up to the reality of essential bodily functions. With the typical condescension of the high-minded, he worries that ordinary people – people with stunted imaginations and intellects, who in his view are barely civilised – will be corrupted by the profane images Norman is producing.

Anthony’s debates with Norman force him to confront his belief that sin can be transmitted via the eye. As the priest worries what will happen to ‘most people’ who view Norman’s paintings, the artist declares the female body to be the ‘most beautiful thing in the world’ and sardonically asks Anthony whether he’s worried about it turning him into a ‘ravenous maniac’. It’s very possible that Anthony is concerned because he so prizes his own ‘civilised’ nature but subconsciously senses how thin it might be. To borrow from heterodox feminist writer Camille Paglia, his character is an example of how ‘civilized man conceals from himself the extent of his subordination to nature’, whereas eroticism functions as ‘the intricate intersection of nature and culture’.[8]Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, Yale University Press, London & New Haven, CT, 1990, p. 1.

Even if he has a greater resistance to sin than most, Anthony still becomes aware – through an act of voyeurism – that Estella is becoming increasingly attracted to corruption. After she chides him for having ‘too high an opinion’ of her (alluding to his need for innocence, even in sex), he tries to convince her that he isn’t as pristine as she might think. ‘I’ve done plenty of things I’m ashamed of,’ he assures her, although the confession that follows is lame and unconvincing.

The highly civilised Estella, as it turns out, is not so much innocent as contained – her voyeurism, and the imagery she is exposed to, breaks that container. Her sensuality is awoken and she begins to lust after the apparently blind handyman, after witnessing him masturbate while sunbathing. Interestingly, the only way she can consummate this lust is by pretending to be somebody else. She takes on the guise of the virginal Giddy (Portia de Rossi), whose desire for the handyman Estella has been encouraging. Norman witnesses her visit the handyman’s room, which presumably inspires him to paint her naked in the company of the estate’s sexually liberated women, whose company she has now joined.

Anthony is, of course, horrified to see his wife painted in such a manner, and threatens to sue. Estella merely comments that her portrait is a good likeness, suggesting she has learned to reconcile with the libidinous version of herself who previously needed a disguise to act on her passions. Yet, while Anthony might struggle to adjust to his wife’s corruption at the hands of Norman and the sirens, the final scene – in which she teases him to public arousal with a stockinged foot – suggests he might yet benefit from Estella’s liberation. Their relationship is more playful for her awakening, and there is a suggestion that Anthony has come to realise that he actually loves his wife in a less chaste and idealised way than he had previously imagined.

Feminism and the sirens

While this focus on female liberation suggests Sirens aspires to be a feminist film, it is now difficult to watch outside the lens of #MeToo. Were it made today, would the film paint Lindsay in such sympathetic terms? His obsession with the female form is easy to pathologise, playing into dominant modern narratives about art and male power, in which men use the veil of genius to sexually exploit or oppress women.[9]See Amanda Hess, ‘How the Myth of the Artistic Genius Excuses the Abuse of Women’, The New York Times, 10 November 2017, <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/10/arts/sexual-harassment-art-hollywood.html>, accessed 15 February 2022. Duigan himself has been the subject of such allegations from actor Thandiwe Newton; see Katie Glass, ‘The Interview: Thandie Newton, Actor’, The Sunday Times, 19 March 2017, <https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-interview-thandie-newton-actor-2pr3v0lgf>, accessed 15 February 2022. Duigan uses the presence of Norman’s wife, Rose, to defuse concerns about exploitation or oppression: she is portrayed as an intelligent, forceful woman clearly comfortable with her own sensuality and unthreatened by the presence of three other beautiful and frequently naked women. So where does the power in these dynamics lie?

From a twenty-first century perspective, it can be difficult to advance an argument for female sexual liberation from a film made by a man about a male genius, featuring lots of naked women as a key selling point.

The title’s invocation of the mythical sirens of Greek lore makes it clear that Duigan sees female sexuality as being a powerful force that can render men weak. And yet he plays with this by having Estella as our protagonist (although Grant wins top billing, the film belongs to Fitzgerald); it is she who is lured into dangerous waters. But the mythical allusions also make clear the manner in which the Church – and men more broadly – have feared the female body as much as they have desired it, and how the institution has, throughout Western history, attempted to deny or curtail female sexuality. Norman is explicit about this, telling Anthony that, ever since Eve was first blamed for the fall of man, women have been taught by the Church to feel guilty about their sexual nature and men have been taught to fear it.

In The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality, Catherine Blackledge examines this fear of the female form, illustrated by the concept of ‘anasyrma’, in which a woman lifts her skirt to expose her vulva – a gesture so powerful that it can scare off the Devil himself.[10]Catherine Blackledge, The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2003, p. 12. (This echoes Mulvey’s argument that the male gaze functions to objectify women in part out of a fear of bodies without penises, driven by castration anxiety.[11]Mulvey, op. cit., p. 6.) In parts of Africa, the gesture is believed to cause great (if largely symbolic) harm to men; while, throughout Europe, grotesques called Sheela-na-gigs adorn buildings to ward off evil or death itself. Blackledge points out that the fear of the female body in the West is a peculiarly modern phenomenon, mirroring Duigan’s allusions to pre-Christian mythology:

In classical Greek, people such as Hippocrates, Aristotle and Homer wrote about female genitalia using the term aidoion, which […] derives from a word meaning to stand in awe or to fear or regard with reverence.[12]Blackledge, op. cit., p. 59.

From a twenty-first century perspective, it can be difficult to advance an argument for female sexual liberation from a film made by a man about a male genius, featuring lots of naked women as a key selling point (although, in Duigan’s defence, there are also scenes of full-frontal male nudity). While Sirens’ protagonist is female, it could be argued that Estella’s voyeurism perpetuates the oppression and Othering of the male gaze, since her looking is ultimately about the effect it has on her, rather than on the object of her gaze. In a piece for The Conversation, academic Janice Loreck argues there is no direct female equivalent to the male gaze, given its role in fostering ‘a patriarchal status quo, perpetuating women’s real-life sexual objectification’. Loreck points out that films that focus on women’s sexual pleasure – as Sirens arguably does – still tend to be more severely censored, underlining Blackledge’s (and Duigan’s) argument that female sexuality remains widely feared.[13]Janice Loreck, ‘Explainer: What Does the “Male Gaze” Mean, and What About a Female Gaze?’, The Conversation, 6 January 2016, <https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-does-the-male-gaze-mean-and-what-about-a-female-gaze-52486>, accessed 18 January 2022.

To defend Sirens is to ask a question that, in 2022, can seem as transgressive to progressives as Lindsay’s work once appeared to conservatives: is objectification necessarily a bad thing? As we’ve seen, Duigan’s film portrays voyeurism as common to both sexes. In this telling, to look and desire is a natural instinct, one that can liberate us from social constraints which make us less human and stultify our most meaningful relationships. This philosophy may not align with that argued for by Mulvey in 1975, but has much in common with Paglia’s position. The latter’s essays in Free Women, Free Men paint looking as something to embrace, rather than reject. When promoting the book in 2017, she stated in interview:

I believe in objectification. The human eye makes objects. That’s kind of my philosophy of art. There’s all this demonization of the so–called ‘male gaze.’ It’s such a bunch of malarkey. Human visual faculties are very tied up with eroticism as well as idealization of every kind.[14]Camille Paglia, quoted in Sarah Boesveld, ‘Camille Paglia Cuts the “Malarkey”: Women Just Need to Toughen Up’, Chatelaine, 4 May 2017, <https://www.chatelaine.com/living/books/camille-paglia-free-women-free-men>, accessed 19 January 2022.

In other words, to look is to lust. Sirens argues that objectification is inevitable, but that the power dynamic involved is unpredictable. Instead of denying a human attraction to beauty and bodies, the film suggests that we should instead debunk the notion that to look and to desire are the sole preserve of male sexuality. The ‘male’ gaze may not be exclusively male; female sexuality and desire is an equally powerful force demanding increased recognition. On the face it, this seems a refreshing and even empowering notion: that, regardless of our sex, we all experience lust – we all like to look – and that we should at least be honest about it. Art and images may well corrupt, but they can also liberate – a liberation that should be extended more widely, rather than be increasingly constrained, lest we too become ‘wowsers’ and ‘Wesleyans’.

Endnotes

| 1 | Janet Maslin, ‘Naughtiness in Pooh Land’, The New York Times, 4 March 1994, Section C, p. 16, available at <https://www.nytimes.com/1994/03/04/movies/review-film-naughtiness-in-pooh-land.html>, accessed 15 February 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Hal Hinson, ‘Sirens (R)’, The Washington Post, 11 March 1994, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/style/longterm/movies/videos/sirensrhinson_b009e1.htm>, accessed 18 January 2022. |

| 3 | Hugh Grant, in the featurette Informal Home Movie Chat Between Hugh Grant and Director John Duigan, Sirens, Blu-ray, Umbrella Entertainment, 2021. |

| 4 | Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, Autumn 1975, p. 12. |

| 5 | See, for example, David Stratton, ‘Sirens’, Variety, 7 March 1994, <https://variety.com/1994/film/reviews/sirens-1200436397/>, accessed 15 February 2022. |

| 6 | See Joe Dolce, ‘Norman Lindsay: Eros and Obscenity’, Quadrant, 27 November 2013, <https://quadrant.org.au/magazine/2013/11/eros-obscenity-norman-lindsay/>, accessed 17 January 2022. |

| 7 | See featurette ABC Lively Arts Interview with Norman Lindsay, Sirens, Blu-ray, Umbrella Entertainment, 2021. |

| 8 | Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson, Yale University Press, London & New Haven, CT, 1990, p. 1. |

| 9 | See Amanda Hess, ‘How the Myth of the Artistic Genius Excuses the Abuse of Women’, The New York Times, 10 November 2017, <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/10/arts/sexual-harassment-art-hollywood.html>, accessed 15 February 2022. Duigan himself has been the subject of such allegations from actor Thandiwe Newton; see Katie Glass, ‘The Interview: Thandie Newton, Actor’, The Sunday Times, 19 March 2017, <https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-interview-thandie-newton-actor-2pr3v0lgf>, accessed 15 February 2022. |

| 10 | Catherine Blackledge, The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ, 2003, p. 12. |

| 11 | Mulvey, op. cit., p. 6. |

| 12 | Blackledge, op. cit., p. 59. |

| 13 | Janice Loreck, ‘Explainer: What Does the “Male Gaze” Mean, and What About a Female Gaze?’, The Conversation, 6 January 2016, <https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-does-the-male-gaze-mean-and-what-about-a-female-gaze-52486>, accessed 18 January 2022. |

| 14 | Camille Paglia, quoted in Sarah Boesveld, ‘Camille Paglia Cuts the “Malarkey”: Women Just Need to Toughen Up’, Chatelaine, 4 May 2017, <https://www.chatelaine.com/living/books/camille-paglia-free-women-free-men>, accessed 19 January 2022. |