In 1788, eleven ships carrying over 1400 men, women and children arrived in Australia, bringing with them an agenda of colonisation and an abundance of mysterious diseases.[1]See ‘First Fleet’, Google Arts & Culture, <https://artsandculture.google.com/story/first-fleet-state-library-of-new-south-wales/zAURIml9CVl_Kw?hl=en>, accessed 29 April 2022. But what if something else – something sinisterly supernatural – arrived with the First Fleet?

An eight-episode series created (and also co-written and co-directed) by Warwick Thornton and Brendan Fletcher, Firebite explores an alternative history of Australia strewn with monsters and metaphors. ‘“What if the vampires came on the First Fleet, and as the colonisation spread across Australia, so [did] the vampires?”’ Fletcher recalls Thornton initially proposing. ‘My brain just exploded [with] all the metaphorical stuff … but Warwick said, “Let’s have some fun bro.”’[2]Brendan Fletcher, quoted in ‘Firebite: Warwick Thornton and Brendan Fletcher on Fire’, FilmInk, 17 December 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/firebitewarwick-thornton-and-brendan-fletcher-on-fire/>, accessed 29 April 2022. Some minor adjustments in punctuation for clarity. Exploring the intergenerational trauma of colonisation may not exactly scream ‘fun’ on paper; but, with Thornton and Fletcher at the wheel, supported by an array of local talent both in front of and behind the camera, Firebite tasks itself with celebrating Indigenous culture as much as reflecting on the history of attempts to destroy it.

The creators of Firebite are no strangers to authentic storytelling: Thornton is best known for his multiple-award-winning features Samson & Delilah (2009) and Sweet Country (2017); while fellow Australian screen veteran Fletcher has directed Mad Bastards (2010) and numerous small-screen documentary projects over the past two decades. Exclusively soundtracked by Australian music, the series is a fast-moving, action-packed whirlwind of blood and guts that also tells a touching journey of self-discovery and coming of age. Although the ambition of its creators may have at times outstripped the series’ budget to its visual detriment – some of the vampire special-effects make-up resembles the work of a high school theatre production, for instance – the results are highly original.

Although the ambition of its creators may have at times outstripped the series’ budget to its visual detriment, the results are highly original.

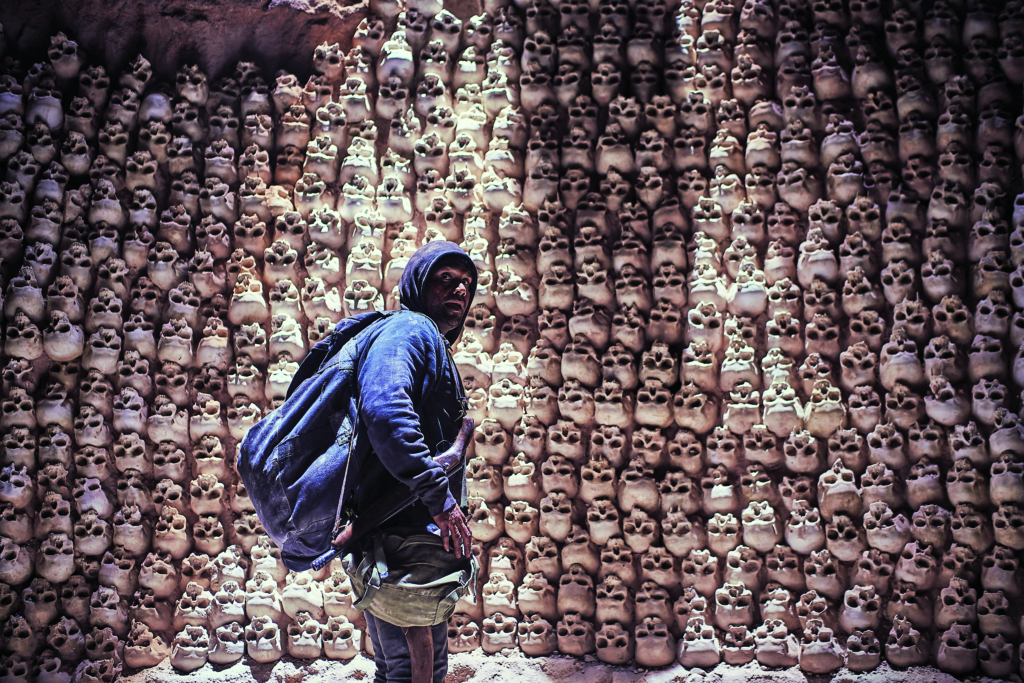

Firebite’s vampire-hunting protagonists, recklessly free-spirited Tyson (Rob Collins) and quick-witted, stubborn teenager Shanika (Shantae Barnes-Cowan), are a duo of desert bandits living in Opal City – a fictionalised stand-in for South Australian desert town Coober Pedy, where Firebite was shot – who take on the antagonistic forces of social services, alcoholism and high school as they hunt down what remains of the last white colony of bloodsuckers in Australia. In a voiceover that opens the first episode of the series, as the camera glides over white sand dunes peppered with holes and tunnels, Shanika tells us, ‘This has been our home for 80,000 years.’ By ‘our’, she means Indigenous Australians, the leading forces of the show’s production and narrative alike; as much as Firebite is a work of speculative fiction, it’s also a reimagining of colonial history. The effect of this juxtaposition is a sense of cognitive dissonance between what we know of the First Fleet and what we see on screen; the buffer of fantasy enables the show to explore factual themes of cultural erasure and generational trauma. This, for the show’s creators, was essential in establishing the right tone for the series: Fletcher notes that the ‘anger’ and the ‘heaviness of the themes’ had to be balanced by a ‘sense of momentum and fun’. It’s a show about vampires, after all. ‘While people can think what they want about the themes of the show, we want them to enjoy the ride,’ Fletcher insists. ‘It’s a genre show.’[3]ibid. Emphasis in original.

As comical as some of the violence is in Firebite – action sequences are soundtracked by frenetic punk rock, interspersed with freeze-frames of vampires getting their rotten teeth knocked out – there’s a tense undercurrent as the vampires creep ever closer to Opal City’s Aboriginal community. Indigenous Australians start to go missing in the dead of the night, but Shanika’s warnings about the vampire colony are dismissed with harmful racial stereotypes. ‘She’s drunk, just like the rest of them,’ one classmate mocks. Her story is dismissed as make-believe, her accounts disregarded in favour of the white colonial history that fills the textbooks. And while vampires may not exist beyond the confines of Firebite’s storyworld, this easy dismissal of Indigenous lived experience is sadly far from fictional.

Firebite is a product of genuine – and successful – representation in storytelling, and serves as a breath of fresh air in a culture that is still learning whose stories are whose to tell. Just last year, Hobart arts festival Dark Mofo, hosted by the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), ran a call-out to descendants of peoples colonised by the British Empire – and particularly those of First Nations backgrounds – to participate in an artwork by Spanish conceptual artist Santiago Sierra; titled Union Flag, the piece was to entail a British flag soaked in their blood.[4]James Dunlevie, ‘British Flag to Be Soaked in Indigenous Blood as Part of Dark Mofo Art Performance’, ABC News, 20 March 2021,<https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-23/aboriginal-outrage-dark-mofo-union-flag-prompts-cancellation/100022680>, accessed 29 April 2022. Met with an overwhelming wave of backlash, the festival cancelled the performance and apologies were dealt out, but the question of how the project could have made it that far in the first place remained. For many, Sierra’s project was just another attempt by a white interloper to portray a history that wasn’t theirs. ‘We want your blood,’ the original call-out read; but as Yorta Yorta hip-hop artist and activist Adam Briggs pointed out, ‘We already gave enough blood.’[5]Adam Briggs, quoted in Kelly Burke, ‘“We Made a Mistake”: Dark Mofo Pulls the Plug on “Deeply Harmful” Indigenous Blood Work’, The Guardian, 23 March 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2021/mar/23/we-made-a-mistake-dark-mofo-pulls-the-plug-on-deeply-harmful-indigenous-blood-work>, accessed 24 August 2022.

In the hands of Thornton and Fletcher, in contrast, Firebite places the storytelling onus on those who’ve lived it. Vampires might not be real, but the struggle for sovereignty is; accordingly, the fantasy genre provides a lens through which to explore such issues. As the white vampires prey on the blood of the Indigenous residents of Opal City, it’s up to Shanika, Tyson and, eventually, others in the Aboriginal community to fight back. While the authorities are almost nowhere to be seen – apart from when they mistake Shanika’s vampire-hunting bruises for domestic violence and propel her through the mess of social services – it’s up to this ragtag bunch of desert bandits to take on the bloodthirsty parasites alone. Armed with chopstick-shooting machine guns and vampire-murdering boomerangs, the hunters and their fellow community members are, quite literally, deadly. ‘The right way or wrong way, we’ve fought for too many years to save this country,’ community elder Aunty Maria (Tessa Rose) says in response to suggestions of taking on the vampire army. ‘I’ll be buggered if I’m giving up now.’

While Firebite tasks itself with exploring a plethora of heavy themes, the series balances out these more serious elements by using violence as comic relief. ‘We knew the violence had to be comical in a strange way,’ Thornton says.[6]Thornton, quoted in ‘Firebite: Warwick Thornton and Brendan Fletcher on Fire’, op. cit. And comedy is never far from the surface thanks to Collins’ expert comic timing, which is often at the forefront of the action. In contrast with the younger Shanika, who is generally presented as the more mature member of the duo, Tyson is often shown cracking inappropriate jokes and toying with the vampires. After being hit by a vampire in one scene, he doubles over, his face breaking into a distressed sob; we are led to believe his act only for a beat until he cracks a cheeky smile, raises his fist and takes on multiple vampires at once, cackling all the while. Even though some of these fight scenes are stitched together with clumsy editing and littered with obviously fake punches, the sheer fun of the action makes this clunkiness excusable.

Everywhere they turn, the series’ protagonists are confronted with questions of identity. Outcasts of a too-small desert town, Tyson and Shanika don’t really fit in anywhere in Opal City, except with each other. Respectively too loud for the local watering hole, where the mostly white miners knock off and overcrowd the pool tables with warning glances in Tyson’s direction, and for the classroom, where Shanika’s mostly white classmates and teacher meet her warning of vampires with sniggers and racist assumptions, this misfit pair seem most able to be themselves when they’ve got one thing on their minds: vampires.

In fight sequences complete with ecstatic squeals and videogame-like combat, Shanika and Tyson are for a few moments able to forget their differences and remember why they’re a team. When they attack vampires, they are able to forget the fragility of their partnership and instead embrace competitiveness and childlike fun. In these sequences, the editing, the at times amateur effects and in particular the frenetic soundtrack combine to paint the show’s protagonists with the bravado of action-film heroes.

At Firebite’s heart is a celebration not only of Indigenous identity but also of Australian culture more broadly, most evident in its music selections. Ranging from Melbourne punk-rock royalty like Amyl and the Sniffers to mosh-friendly bands like Private Function, the show’s soundtrack is cluttered with a who’s who of up-and-coming Aussie rock outfits. This decision not only emphasises Thornton and Fletcher’s mission in spotlighting Australian talent both in front of and behind the screen but also accentuates the connection to pride in culture the show explores. Despite being buried on US-based subscription service AMC+, Firebite has the feeling of being an Aussie production through and through. From the characters’ accents to the songs that accompany fight scenes – Private Function’s chaotic ‘I Wish Australia Had Its Guns Again’ provides the backing for one of the more epic action sequences – the series’ local authenticity is unquestionable.

It’s inspiring not only for the creatives that are involved in the making of the show but also for Australian audiences – whether or not they work in creative industries themselves – to see local culture celebrated on screen.

Using local talent on the show’s soundtrack was a significant choice for Thornton. In an interview with The Music, he describes one of the rules he had when making the show was that ‘every single song [had] to be by an Australian band’.[7]Warwick Thornton, quoted in ‘New TV Series to Showcase Aussie Artists to Millions Worldwide’, The Music, 16 December 2021, <https://themusic.com.au/news/firebite-australian-vampire-tv-series-soundtrack/3HvEzvHw8_I/16-12-21>, accessed 29 April 2022. After nearly two years of scarce income for many creatives around the country due to the pandemic and its resulting border closures and lockdowns, Thornton understood that the best way to support those in the local industry was through showcasing their work. ‘None of these bands could tour. None of them could do anything. And they’re great bands and they’ve got amazing music and they’ve got a lot to say in their lyrics,’ he says. ‘And it’s like, well, that’s the kind of music we want.’[8]ibid. It’s inspiring not only for the creatives that are involved in the making of the show but also for Australian audiences – whether or not they work in creative industries themselves – to see local culture celebrated on screen.

Among the plethora of television clogging our streaming services, only a fraction is authentically Australian. Getting to see a representation of this country on screen – one that feels authentic, raw and original – is a pleasure Australian viewers aren’t often afforded. Even if genre TV or punk rock aren’t your thing, the rare treat of unique Aussie TV that you can be proud of surely is.

Endnotes

| 1 | See ‘First Fleet’, Google Arts & Culture, <https://artsandculture.google.com/story/first-fleet-state-library-of-new-south-wales/zAURIml9CVl_Kw?hl=en>, accessed 29 April 2022. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Brendan Fletcher, quoted in ‘Firebite: Warwick Thornton and Brendan Fletcher on Fire’, FilmInk, 17 December 2021, <https://www.filmink.com.au/firebitewarwick-thornton-and-brendan-fletcher-on-fire/>, accessed 29 April 2022. Some minor adjustments in punctuation for clarity. |

| 3 | ibid. Emphasis in original. |

| 4 | James Dunlevie, ‘British Flag to Be Soaked in Indigenous Blood as Part of Dark Mofo Art Performance’, ABC News, 20 March 2021,<https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-03-23/aboriginal-outrage-dark-mofo-union-flag-prompts-cancellation/100022680>, accessed 29 April 2022. |

| 5 | Adam Briggs, quoted in Kelly Burke, ‘“We Made a Mistake”: Dark Mofo Pulls the Plug on “Deeply Harmful” Indigenous Blood Work’, The Guardian, 23 March 2021, <https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2021/mar/23/we-made-a-mistake-dark-mofo-pulls-the-plug-on-deeply-harmful-indigenous-blood-work>, accessed 24 August 2022. |

| 6 | Thornton, quoted in ‘Firebite: Warwick Thornton and Brendan Fletcher on Fire’, op. cit. |

| 7 | Warwick Thornton, quoted in ‘New TV Series to Showcase Aussie Artists to Millions Worldwide’, The Music, 16 December 2021, <https://themusic.com.au/news/firebite-australian-vampire-tv-series-soundtrack/3HvEzvHw8_I/16-12-21>, accessed 29 April 2022. |

| 8 | ibid. |