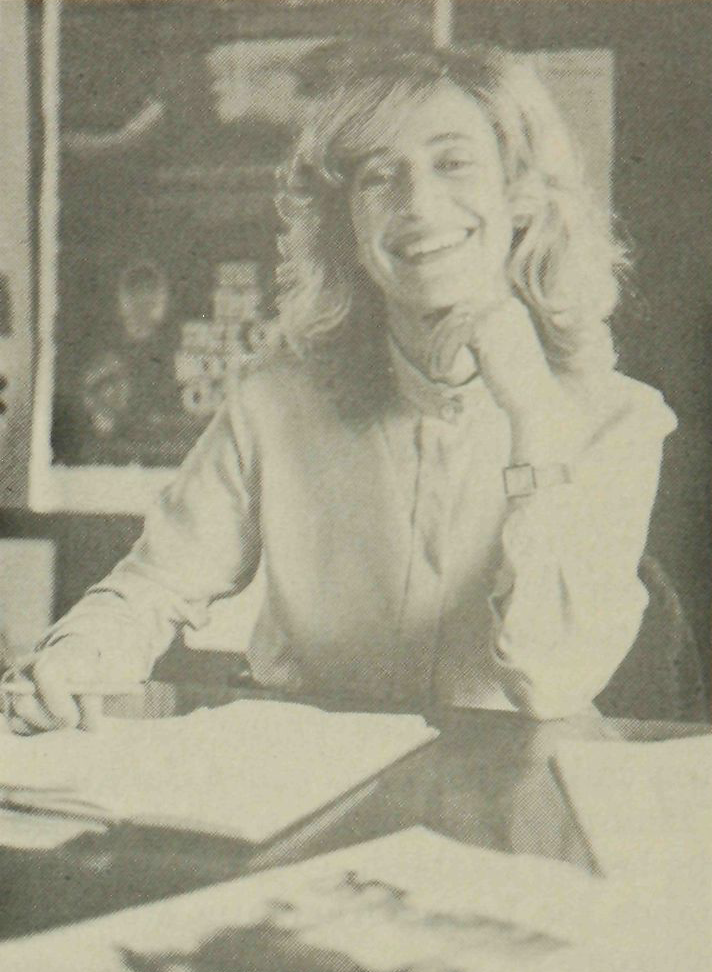

Natalie Miller

Natalie Miller is perhaps best known through her film distribution company, Sharmill Films, bringing to Australian cinema such films as Bunuel’s classic, The Exterminating Angel, the commercially successful Tree Of Wooden Clogs, and films either of Australian content such as I Can Jump Puddles or the early work of Australian directors/producers such as Gillian Armstrong’s The Singer And The Dancer and Esben Storm’s 27A.

Natalie Miller has been an important figure in the Australian film industry as public relations co-ordinator over several years for the Melbourne Film Festival, and as a foundation and board member of the Victorian Film Corporation and more recently with the Women’s Film Fund. She has also been actively involved in film production as Associate Producer of In Search of Anna and now as Producer of her first feature film The Perfect Family Man.

Natalie Miller’s career might be traced back to the Saturday matinees and the kid’s film club, but it was the business practise she learned on a small trade paper which led her into public relations work and then to journalism.

As a graded journalist she moved to publicity with ABC television. After the birth of her first child she began freelance work for television, the Film Festival, theatre and the arts, until,

“I suddenly decided, why should I be promoting other people I might as well promote a film for myself. At the time I was thinking a lot of the good films at the Melbourne Film Festival that had never been bought from past festivals, The Exterminating Angel for instance. Bunuel’s film was one that had never been brought to this country before so I took the plunge and – I probably had my second child then or was it my third, I can’t remember, probably the second – I bought the rights to it and that was really the beginning of being in distribution.”

It was incidental, though fortuitous that a change in the direction of her career fitted with the demands of a growing family. “I consciously made a decision to run my business from my home and that fitted. I could’ve kept doing P.R. work but I felt like taking a new challenge, taking a risk, doing it myself. I found that I liked it so much that I cut down on the P.R. work and furthered my distribution interests. Concurrently I kept doing publicity for the Australian Film Awards and maintained interest in the Australian film industry. So, very early on I had an interest in everything that was going on in the Australian film scene which of course then led me to have certain production interests as well”.

These production interests have led Natalie to be producer of her first feature film, The Perfect Family Man.

“The film is scripted by Alan Hopgood and directed by Malcolm Robertson who has been a stage director for twenty-five years and did the Australian Film and Television School’s course which trained a number of stage directors. Malcolm asked me to produce his short film for the A.F.T.S. course, The Quick Brown Fox which was also scripted by Alan Hopgood who had earlier given me the script of The Perfect Family Man to read. I thought, oh, yes, a commercial comedy but maybe a bit superficial on first reading. It was when I saw what Malcolm Robinson could do with the rather superficial script of Quick Brown Fox that I thought if any director is going to do something with the Perfect Family Man script it would be Malcolm. It would be terrific.

“The film itself is about a man in his late thirties, a mature man who has an affair. So, you may ask, what’s new. But the film is designed as an up-market comedy. We see it being done in the style of Woody Allen or the Dudley Moore film 10, an Australian comedy as opposed to an ocker comedy”.

Natalie’s position as a distributor of quality films has given her a unique insight into the industry. “If you had a sex film I suppose all you have to do is lay up the cash, stick it in a theatre and hope you’re going to reap the rewards. With the sort of art product that I’m involved in that doesn’t interest me. There has to be a build-up of the reputation for quality films and therefore there is more in the distribution.

“Firstly you decide what you want to buy. Someone’s either drawn my attention to it, or I’ve seen it at the Melbourne Film Festival or, in recent years, I’ve been going to the Cannes Film Festival. You see the films and then make a conscious decision about what you want to do. For instance, I saw Best Boy at Cannes last year. It was on at the Melbourne Film Festival and the director, Ira Wohl was here. I really chased to get that, and though it was a difficult film commercially it was a challenge.

“Once you’ve bought – you buy the right for a period of years, five or seven or whatever the contract says – then it’s up to you to find which theatre is most suitable, and in most cases with these films you pay a certain up-front amount and then you’re on residuals with the overseas person. It’s up to you to try to make the film work.

“Say in the case of Best Boy, that was a challenge; to know that it wasn’t a case of just putting it on, you had to do a tremendous amount of work to get through to the disabled groups, to schools, to organisations and that’s the part I enjoy because the promotion scene’s my baby. And, in my terms, Best Boy has been successful, though not necessarily in Village theatre terms.”

One of the harsher realities for Natalie Miller is that as an independent distributor, her competitors are the big commercial distributors all of whom have their own outlets.

“I have an amicable relationship with them all. The big people consider you as running a fairly small business and so they don’t really regard you as competition. But I am as entitled as anyone else to go to Village for example and ask if the film could go to say the Rivoli. I would say the most damaging thing as a commercial independent trying to compete is not owning the cinema. People have been known to put films on – and this has happened to all us independents – then it might come the school holidays or Christmas or something, and unless it’s really hot property they’re not going to give you the Christmas stakes, are they? So you’re really dying with the fact that you don’t own a cinema.

“Although I can’t do everything, and when I do something I like to do it myself, I’ll have to decide whether I’m going to stay with film production. And I guess, in the long term, I’d love to own a little independent art cinema in Melbourne”.

Despite working in what has been a male-dominated industry, Natalie believes that women producers are considered at least as efficient as men.

“I am not a camera woman or a grip where they’ll say women can’t carry cameras or climb ladders, so I’ve never really found that doing my job as a woman has been a disadvantage. But I’m now on the Women’s Film Fund and so I’m seeing more closely the problems women are having. I can see the areas of discrimination and the difficulties for women particularly in filmmaking. We interviewed a woman who wanted to be a technical director and that was really an eye opener to the attitude men had to her. I’m quite aware that there is discrimination against women in the industry but it hasn’t been a problem to me.”

As both producer and distributor, Natalie has strong feelings about the recent legislation in relation to tax concessions for the industry, making a twelve month production financially necessary.

“We are going to have that pressure ourselves all things being equal and The Perfect Family Man gets moving – we might decide in our wisdom as producers that it should stay in the editing room another three months. That’s what happened to Mad Max. Imagine if someone had put the pressure on Mad Max and made it come out of there. I mean they took months to edit it. So of course it puts the pressure on and you are going to have films pulled out of editing rooms because they have to be finished, when those films should have stayed in longer”.