A loosely connected, non-chronological series of short episodes linked by a woman who receives a mysterious box of objects from the dark web, Deadhouse Dark is a new horror anthology web series that was released on the subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) platform Shudder in April 2021. I spoke to the show’s producers, Enzo Tedeschi and Rachele Wiggins, about the creation of Deadhouse Dark, its style, the deal with Shudder and the challenges of the web series format.

Mark David Ryan: What was the inspiration for Deadhouse Dark?

Enzo Tedeschi: It is a combination of a few things. After [co-director Julian Harvey and I] made The Tunnel [2011], I spent a lot of time in the web series space – so shortform episodic was not something that I was afraid of. I say that because a lot of people don’t quite get [web series as a production format]. Then, creatively, I’ve always been a fan of anthology storytelling. I grew up watching Creepshow [George A Romero, 1982], [as well as the 1980s series of] The Twilight Zone, and I am a huge fan of Black Mirror. When Rachele and I started thinking about what projects we were going to develop together, we were like, ‘Let’s start looking at something like this.’ It was an opportunity to take the anthology format, which I’ve done a few times, but never really felt like I was able to make my own in terms of a creative style.

The stories are loosely linked. When I say ‘loose’, it was really loosely linked, and I think that a lot of people prefer things to be a lot more obvious. But there are people who are really intrigued by it and connect to as much as they need to be able to have a good time. But it is interesting that the criticism [of the series] seems to be, often, ‘Linked? What link? Nothing was linked.’

How are the stories linked?

ET: Thematically, it was about looking at recent social trends. Then Rachele and I started thinking about how to build out the world around these stories. Again, the reveals are there.

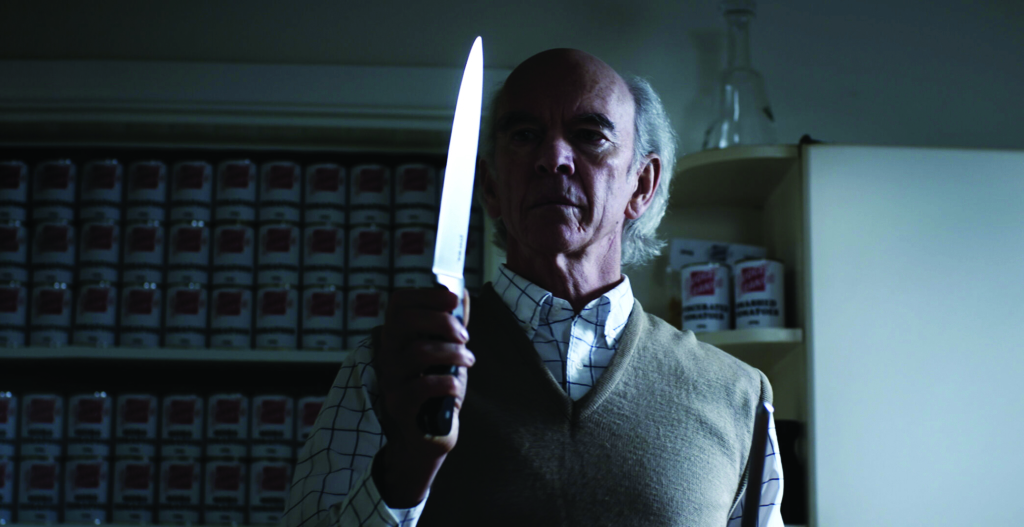

In the episode Rachele directed [‘Mystery Box’], you have to be sharp or you’ll miss [the links], but they revolve around Nicholas Hope’s character from my episode [‘A Tangled Web We Weave’], where he’s the mastermind pulling the strings behind a lot of this stuff. He was responsible for Sophie’s mum’s death in ‘Mystery Box’. It’s his voice on the phone in ‘No Pain, No Gain’, so he’s obviously murdered the coach and taken his place.

That stuff’s all there, but it is not [at the] forefront […] We wanted it to feel like everything exists in the same world – these people inhabit the same space, but they don’t necessarily interfere in each other’s lives, strictly speaking.

Rachele Wiggins: There is also a very simplistic link, which is [that] there is an object from each episode which features in the ‘Mystery Box’ episode as well. There are also music cues and lots of subtleties, but there are very obvious clues that sometimes people actually miss. Objects from each episode are, literally, sometimes centre-frame – like the pills, for instance, from ‘No Pain, No Gain’. They’re in the shot, and a lot of people don’t realise that’s the same pill bottle in ‘Mystery Box’.

Audiences often feel like they’re spoonfed. The irony of that is [that] when you don’t make material obvious, people also criticise it. But we went for subtlety because we wanted to give audiences the opportunity to see something where they go, ‘Hang on, was that in that episode?’ and then they go back [and] rewatch and rematch, which is also a bit of a commentary in and of itself on the idea that, sometimes, people are not paying attention [to what they’re watching] because there’s so much in their phones or their laptops or whatever.

How did the collaboration with the directors of each episode happen?

ET: Essentially, Rachele and I started making a list of people that we thought would be fun to work with – really exciting voices. Maybe, in some cases, they hadn’t had a decent opportunity to be able to show what they could really do, but we knew they could [nail] it if they had the opportunity. From there, we just started going down the list in terms of ‘these are the most exciting’. We didn’t have to get very far. I think the people we got were the top of our list.

‘Horror is so diverse, and it really comes down to what you perceive as frightening, what makes you fearful or scared, and everybody’s fears are completely different to each other’s.’

– Rachele Wiggins

RW: We were happy because it was also about getting a team that felt different. So, yes, it was about different visions and supporting new, emerging talents, but also having a group of people that felt different enough that it would be exciting. We also wanted to ensure that there is something for everyone, because horror is so diverse, and it really comes down to what you perceive as frightening, what makes you fearful or scared, and everybody’s fears are completely different to each other’s.

What were the production processes involved? Did each director have a brief?

ET: In terms of the story-development and script-development process, some of the stories we pitched to the directors – ‘Dashcam’, was one of those – [were] based on a story I had written. I sent that off to Rosie [Lourde], and she responded to it in a way that I think even she didn’t expect. We ended up writing the rest of that together. But in other instances, like with Denai Gracie [‘The Staircase’], or Joshua Long’s episode [‘My Empire of Dirt’], it was a bit more ‘pitch us something’. Denai came to us with four or five really good ideas, but the one we ended up doing was a standout.

Then we did a workshop with [producer, writer, and head of content and development at Every Cloud Productions] Mike Jones. We did a day with everybody where they brought their scripts in, and we did the Mike Jones thing where he tore them to shreds and made them infinitely better. So that was the development process.

RW: Basically, one of the things that we were really set on was trying to create a consistency amongst the episodes. Because one episode was shot in Queensland, we knew we couldn’t bring the entire crew up, but we did [choose] a strong director of photography and a really strong production designer that could work across the entire series. While episodes had their own vision, there [was] still some underlining uniformity that would bleed through.

ET: They’re the only two production crew that worked across all six. For the Sydney crew, the entire crew was largely the same throughout all the other five episodes. Caitlin Yeo composed [the scores for] all six episodes. Our post-production team was consistent as well – the same editor, composer and sound designer.

I was surprised by how different each episode was.

ET: It’s interesting that, [for] any single given episode, the reactions are miles apart. [One reviewer] for example will go, ‘Oh my God, it’s so predictable. I saw it coming.’ But then there are people that are like, ‘What an ending. I never saw it coming. That’s so exciting.’ Well, I think the worst thing we could have made was to try and write to the lowest common denominator.

‘With a lot of horror, people fear hands getting chopped off and the gore aspect … I think what made this series quite strong was that each character has a fear of something that is very human, everyday and relatable.’

– Rachele Wiggins

RW: I think, with a lot of horror, people fear hands getting chopped off and the gore aspect. But then there’s the other side of fear, which is the psychological. I think what made this series quite strong was that, when you look at it, each character has a fear of something that is very human, everyday and relatable. One girl’s fear is that she’s not going to be good enough, and that leads us down a path. One girl’s fear is that her sister’s going to leave; that leads down a path. Another example in, for instance, Enzo’s episode is about the [protagonist’s] fear of being found out for what he truly is. These are very relatable fears. I’m finding that people are connecting with certain episodes over others.

Are streaming services the new natural home for Australian horror films and series?

ET: I think they already are. Stan has been doing some interesting work in the last few years in terms of original series. Netflix … maybe not so much in Australia, necessarily, but around the world. It is just what we have become accustomed to now; we are used to it. Having to switch off theatrical [distribution] and production over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic really just accelerated people’s acceptance [of SVOD platforms].

It was probably a contributing factor to us signing with Shudder. That was not the original plan; it was an upgrade for us. We were going to release it ourselves, via Deadhouse.tv.[1]See Deadhouse.tv website, <https://www.deadhouse.tv/>, accessed 28 July 2021. We were going to attend [the Cannes International Series Festival] in March 2020 to start our buzz-building and rollout, and we were going to release around the end of the year. When Cannes got pushed back, we decided to just hold back to see what [would happen] and wait until the dust settled. Because of COVID-19, the streaming services became twice as hungry as before for content – so there was an opening in the market.

I had been trying to get a meaningful conversation happening with our contact from Shudder since I first connected with her at the Berlin Film Festival in 2018. Two years later, I sent [Deadhouse Dark] through, almost as much as a ‘thought you might like to see what we have been up to’ conversation as a pitch. Before we knew it, we were talking about an acquisition for the platform, and they decided to take [the series] as an original. It was a massive upgrade for how we were going to reach an audience.

RW: It’s the kind of thing you can’t do if it got made into a second season. To have it launch as a first season was unexpected.

Why weren’t you thinking of releasing the first season via video on demand?

ET: Essentially, the show was designed as a proof of concept knowing that, if the audience was there, we could, if nothing else, do another season of essentially short episodes, which is a lot easier to try and pull off than [a longer television series].

Another reason is format. I think we are one of maybe two shortform episodic projects on Shudder. Everything is a commercial half-hour, or commercial hour. Even their marquee series – such as [2019 small-screen reboot] Creepshow – are forty to forty-five minutes per episode, but they are two stories each. They are still not that much longer than what we did, but they just had more stories and packaged them together into longer episodes.

Thanks to spectacular failings such as Quibi[2]A mobile app released to distribute and monetise shortform content that spectacularly collapsed in 2020. See Steinar Ellingsen et al., ‘Quibi Disaster: How to Lose $1.75b on Something You Don’t Understand’, Screenhub, 10 November 2020, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2020/11/10/quibi-disaster-how-to-lose-175b-on-something-you-dont-understand-261407/>, accessed 28 July 2021. – and the efforts of people like Blackpills,[3]A French production company specialising in the production and distribution of shortform content that shut down its own SVOD app in 2019. See Marina Alcaraz, ‘L’application de vidéos pour mobile Blackpills arrêtée’, Les Echos, 11 April 2019, <https://www.lesechos.fr/tech-medias/medias/lapplication-de-videos-pour-mobile-blackpills-arretee-1008431>, accessed 28 July 2021. who made that entire market really exciting for a while, and then that all largely dried up as well – it is really hard to sell a web series now; […] which is why when I sent the show to Shudder, it was more like, ‘Hey, we made a series. You might want to check it out.’ I almost thought they might not take it, because it just doesn’t really fit with what most platforms are doing.

Shudder is a unique animal in that their job is curation, and they’ve got an audience who want content, and it almost doesn’t matter what the form of the content is, as long as it will keep people coming back or drive subscribers. They saw that this was something viewers could binge that roughly feels like the duration of a movie [and were] like, ‘Well, we can work with that.’

Funding details: this article was supported by the Australian Research Council under its Linkage Projects grant program for a project titled Valuing Web Series: Economic, Industrial, Cultural and Social Value (LP180100626).

Endnotes

| 1 | See Deadhouse.tv website, <https://www.deadhouse.tv/>, accessed 28 July 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | A mobile app released to distribute and monetise shortform content that spectacularly collapsed in 2020. See Steinar Ellingsen et al., ‘Quibi Disaster: How to Lose $1.75b on Something You Don’t Understand’, Screenhub, 10 November 2020, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/2020/11/10/quibi-disaster-how-to-lose-175b-on-something-you-dont-understand-261407/>, accessed 28 July 2021. |

| 3 | A French production company specialising in the production and distribution of shortform content that shut down its own SVOD app in 2019. See Marina Alcaraz, ‘L’application de vidéos pour mobile Blackpills arrêtée’, Les Echos, 11 April 2019, <https://www.lesechos.fr/tech-medias/medias/lapplication-de-videos-pour-mobile-blackpills-arretee-1008431>, accessed 28 July 2021. |