The idea of history can be traced back to a specific point in time. Herodotus’ 430 BC text The Histories is the place in which ‘history’ – as an object of inquiry or genre of discourse – is believed to have emerged, and ‘his story’ was written to serve two purposes: to ‘prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time’, and ‘to preserve the fame of the important and remarkable achievements produced by [civilisations]’.[1]Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Robin Waterfield, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 1998, p. 175. Unfortunately, this narrative view of history failed to reconcile the tension between those organising principles, for the act of commemoration – that is, official remembrance or celebration of past accomplishments – might also result in the attempted erasure (or forgetting, or silencing) of the past within historical time. Perhaps that’s why the ‘father of history’ has also been called the ‘father of lies’.[2]See JAS Evans, ‘Father of History or Father of Lies; the Reputation of Herodotus’, The Classical Journal, vol. 64, no. 1, October 1968, pp. 11–7. History’s narrative logic tends to elide the fact that true and false aren’t so much opposites as they are two sides of the same coin: there can always be competing versions of the same events, or different ways of looking at the same situation.

As a case in point, the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) recently issued recommendations that ‘history’ – as it is conveyed in the classroom – be made more inclusive. Decrying the lack of ‘truth telling’ in the education system, the review raised concerns about the ‘accuracy and adequacy’ of the current approach to teaching history.[3]Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, Cross–curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures, 2021, p. 4, available at <https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/consultation/cross-curriculum-priorities/>, accessed 24 August 2021. The oft-told tales of European ‘discovery’ and white ‘settlement’ should also, it suggested, be seen as an ‘invasion and dispossession’ of the lives and lands of First Nations peoples.[4]ibid. While this attempt at course correction is long overdue, some historians may question the lack of reference to genocide; see Tony Barta, ‘Decent Disposal: Australian Historians and the Recovery of Genocide’, in Dan Stone (ed.), The Historiography of Genocide, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, UK & New York, 2008, pp. 296–322. This acknowledgement of ‘competing world views’[5]Mark Rose, quoted in Jordan Baker, ‘Students to Be Taught About “Invasion” Experience of First Nations Australians in Proposed Curriculum Changes’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/education/students-to-be-taught-about-invasion-experience-of-first-nations-australians-in-proposed-curriculum-changes-20210429-p57nbq.html>, accessed 24 August 2021. is part of an increasingly widespread impetus to unearth previously buried voices,[6]See, for example, James W Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, New Press, New York, 1995; and Jenny Kidd et al. (eds), Challenging History in the Museum: International Perspectives, Routledge, Abingdon, UK & New York, 2016 [2014]. and also encompasses recent attempts to reframe the past on screen.[7]See, for example, Sweet Country (Warwick Thornton, 2017), The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent, 2018) and High Ground (Stephen Maxwell Johnson, 2020), all from Australia; Steve McQueen’s 2020 film collection Small Axe, from the UK; and Barry Jenkins’ 2021 series The Underground Railroad, from the US.

Two 2021 documentary series (or episodic essay films), Raoul Peck’s Exterminate All the Brutes and Adam Curtis’ Can’t Get You out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World – the latter’s subtitle an apt description of each work – provide exemplary case studies. Although these ‘emotional histories’ offer two very different worldviews, the one complements the other. Peck’s four-part HBO work provides a history of white imperialism, colonialism and genocide, while Curtis’ six-part BBC production deals with the destabilising effects of colonisation and how ‘history’ has subsequently occupied and displaced our consciousness. Whatever the differences between their respective reframings of the past, the two series ironically share a common interpretative framework. Like Herodotus, the filmmakers make ‘history’ out of a dizzying array of seemingly unrelated events in order to present a bigger picture.

‘The horror! The horror!’

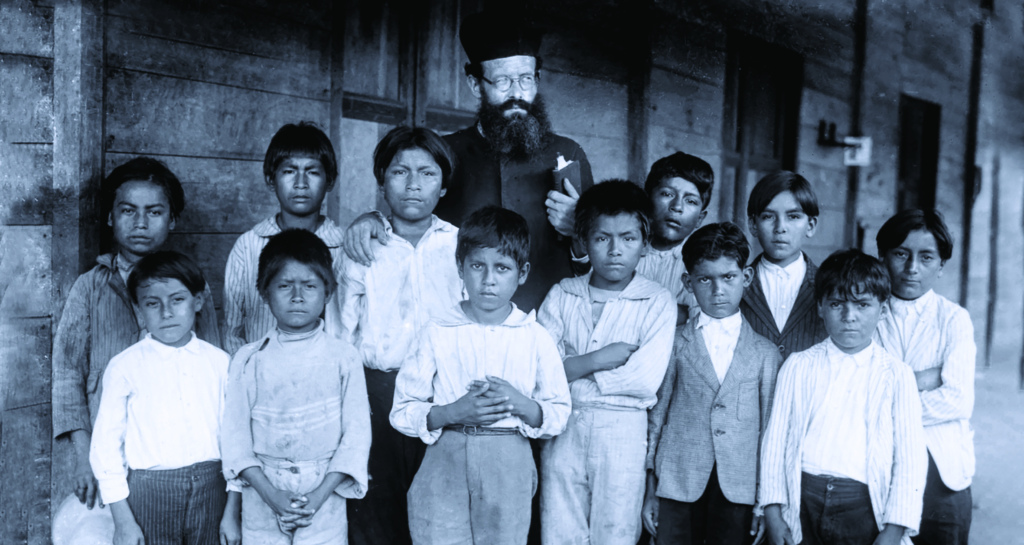

Exterminate All the Brutes attempts to rewrite ‘history’ as it manifests through the founding mythologies of Western cultures: of ‘discovery’, ‘race’, ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’, the whitewashed versions of events taught in schools, perpetuated in popular culture and written into the cultural DNA of national identities. As indicated by the show’s title – an exhortation expressed by ivory merchant Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness[8]Despite its origins in Conrad’s novella, the title of Peck’s series seems to be primarily inspired by the Sven Lindqvist book of the same name, which is drawn on extensively in the series. See Lindqvist, ‘Exterminate All the Brutes’: One Man’s Odyssey into the Heart of Darkness and the Origins of European Genocide, Granta Books, London, 2018 [1996]. The two other primary sources navigating Peck’s journey into the heart of darkness are Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 1995; and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 2014. – this has been a self-serving, self-refuting history, one made up of unspeakable horrors. Is there anything more brutal or savage, after all, than a perceived moral imperative to exterminate classes of people deemed ‘savages’ and ‘brutes’ in the name of human civilisation and progress?

Although the Black Haitian filmmaker’s counter-narrative primarily focuses on European and American history, the same old horror story was also perpetrated here in Australia.[9]See ‘Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788–1930’, The Centre for 21st Century Humanities, The University of Newcastle, Australia, <https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/>, accessed 24 August 2021. Note, for instance, what British writer Anthony Trollope had to say about Indigenous populations when he visited Australia in 1871:

Their doom is to be exterminated; and the sooner that their doom be accomplished – so that there be no cruelty – the better will it be for civilisation.[10]Anthony Trollope, Australia and New Zealand: Vol. II, Bernhard Tauchnitz, Leipzig, 1873, p. 245.

Like many other ‘civilised’ people, Trollope believed that the extermination of ‘inferior races’ was prescribed by the course of history, and that the exterminators were – as HG Wells sardonically put it – ‘apostles of mercy’.[11]A phrase employed by Wells in his novel The War of the Worlds in reference to the atrocities visited upon colonised peoples: ‘The Tasmanians […] were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?’ HG Wells, The War of the Worlds, William Heinemann, London, 1898, p. 5. In his series, Peck attempts to make sense of such horrifying sentiments; in the process, he provides an origin story for Western civilisation’s impetus towards racial supremacy and world domination.

According to Peck’s narration, ‘there are three words that summarise the history of humanity: civilisation, colonisation and extermination’, and he wants viewers to see ‘the different strands of events’ making up this ‘larger story’. From the outset, Peck explicitly reframes the past in narrative terms: his overarching ‘story’ sets out to challenge the postmodern[12]The idea that history can be objective or value-free has been challenged by post-structuralist philosophers (along with those in other disciplines such as philosophical hermeneutics). In this view, the narrative logic of ‘history’ is seen as an intellectually imperialistic enterprise: that is, stemming from a desire to seize control over inherently meaningless or chaotic events and occupy them with rational organisation and understanding. For elaborations and challenges, see Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th–century Europe, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2014 [1973]; Willie Thompson, Postmodernism and History, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2004; and Ewa Domańska, Encounters: Philosophy of History After Postmodernism, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, 1998. view that ‘the historical narrative is just one fiction amongst others’, and his own narrative counters that ‘there are no such things as alternative facts’. Peck wants to dispute the Nietzschean claim that ‘facts do not exist, only interpretations’[13]Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. R Kevin Hill & Michael A Scarpitti, Penguin Random House, London, 2017, p. 287. – but there is irony here in that his interpretation of ‘history’ is itself Nietzschean, as it is primarily seen through a ‘will to power’ narrative that invariably calls into question its own interpretation of existing ‘facts’. Indeed, Peck tells his story by alternating between facts and plotlines to determine ‘who we are today, what we have become as people, and what side of history […] and truth’ societies truly want to be on.

Consequently, Peck’s wielding of a metanarrative remains a double-edged sword.[14]Although Peck disavows the post-structuralist and/or postmodern view of history, he nonetheless uses the term ‘deconstruct’ to describe his grand narrative. Neither Jacques Derrida nor Jean-François Lyotard would approve! The filmmaker views all historical narratives as truth-evaluable – that is, as true or false independent of the interpretative framework – and yet he evaluates the truth or falsity of given narratives relative to historical context (or narrative structure supporting it). He does this to tacitly ask: if the West’s ‘history’ remains grounded in the world of make-believe, what are we to make of the verifiably false beliefs about its claims to racial supremacy and moral superiority? So while Peck argues that officially sanctioned ‘history’ does belong to the genre of fiction, his story invariably raises the question: to what extent is his narrative true or created from his own imagination?

Peck’s rewriting of history, however, isn’t so much about setting the record straight. Many of the events covered should already be familiar to anyone with a passing interest in verifiable ‘history’. The series’ undeniable power is to be found in the way its director imaginatively assembles seemingly disparate events to trace throughlines across intersecting narratives. It is at those historical intersections – divides that pass through or lie across one another – where his own story lies and speaks truth to white power. Peck thereby maps out connecting themes and plots between, say, the transatlantic slave trade, the slaughter of indigenous populations on multiple continents and the genocide of European Jews.

Peck’s historical method is primarily aesthetic, and his access to ‘history’ occurs via a use of collage. Specifically, he creates a bigger picture out of an assemblage and juxtaposition of different media. Primary and secondary sources are given equal evidentiary value, and provide the series with its body (or bodies) of proof. History here is made from the many found, created or altered objects stuck onto the film’s surface and sequenced to condense geographical and temporal distances. Archival footage, film clips, home movies, photographs, news videos, dramatic re-enactments or reimagined scenes, animated sequences, diary entries, book excerpts, time-lapse graphics and extended tracking shots all merge into one another in the series to recontextualise established historical narratives. Although the evidence speaks for itself, Exterminate All the Brutes’ repurposing of sources creates a dialogue between the past and present as different historical narratives speak to (or through) one another. Peck has no need for talking heads to help him authorise this story; his disembodied voice presides over the piling up of corpses and primarily provides his history with its skeletal framework. There is one white figure who does, however, have a recurring presence in the film as the spectre of history: actor Josh Hartnett, who reappears at different times and in different roles to serve as a kind of grim reaper.

Peck’s journey into the heart of darkness resists easy categorisation or encapsulation: the series acquires its power via the accumulation of additional layers of meaning and emotion. Haunting highlights include animated representations of the Native American Trail of Tears and a slave ship transporting a member of its (escaped) cargo to an ocean graveyard. Time-lapse images of humankind’s migration out of Africa are recontextualised via images of European settlers eventually returning to enslave and plunder the ancestral population and grounds of all humankind. The sudden destruction of ancient civilisations is captured in the blink of an eye: we watch history literally being erased as millions of people are wiped off the face of the Earth. A nineteenth-century lecture on the different stages or strata of humanity is delivered to a culturally diverse modern audience, and it is the Ethnological Society of London that is dumbfounded by the outraged responses to its attempt to ‘educate’ audience members. Peck visits a fishing village relatively untouched by time in Senegal, and asks: do any of these people have the right to exist?

Peck’s approach follows the intertwined paths of religion, science, politics and philosophy in order to explore what Jamaican philosopher Charles W Mills calls the ‘racial contract’.[15]Mills argues that the social contract that binds us all together is a racial contract, and that it remains built on the consensual foundations of white supremacy. See Charles W Mills, The Racial Contract, Cornell University Press, New York, 1997. The biological myth of race may have originated in the ‘blood purity laws’ of religious practice,[16]This concept originated within fifteenth-century Spanish Catholicism. See Max S Hering Torres, María Elena Martínez & David Nirenberg (eds), Race and Blood in the Iberian World, Lit, Zürich & Berlin, 2012. but this racial hierarchy invariably found its way into scientific orthodoxy, secular arguments and competing ideologies.[17]Originally attributed to cultural/ethnic variations (with environmental factors enabling genetic continuity and differences between cultures/regions), the modern idea of ‘race’ invariably divided humans into biologically distinct subcategories. For accounts of how the idea of race can be traced back to antiquity, see Denise McCoskey, Race: Antiquity and Its Legacy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 2012; Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ & Woodstock, UK, 2004; and Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA & London, 2014. The Nazis’ Final Solution was therefore no anomaly – it had precedents in the past, and its perpetrators were following the lead of historical counterparts.[18]See Alex Ross, ‘How American Racism Influenced Hitler’, The New Yorker, 23 April 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/04/30/how-american-racism-influenced-hitler>, accessed 24 August 2021. The history of Western civilisation, then, can be seen to follow a Janus-like trajectory that culminated in the industrialised mass murder of those citizens considered to be racially inferior: in service of the past, a war of extermination was waged against millions of indigenous people standing in the way of colonisation and progress; while in service of the future, millions of other indigenous people were kidnapped and transported across the ocean so they could be enslaved to build brave new worlds on newly acquired bloodlands.

Peck’s larger story attempts to inaugurate a reckoning with ‘history’, one deemed urgent due to systemic racism, intergenerational trauma and the unsettling legacies of colonialism. In his voiceover, the director expresses particular alarm over the resurgence of white-supremacist ideology, along with the prevalence of people nostalgic for ethnic cleansings and genocide. Although Peck’s metanarrative makes for compelling storytelling, it nonetheless highlights the limitations of narrative logic and structures – after all, the idea of ‘history’ (like the idea of ‘race’) is socially constructed, and may be called (back) into question at any given time.[19]Interestingly, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists and The American Society of Human Genetics have recently (if only tacitly) disavowed science’s historical role in perpetuating the biological myth of race. See ‘AAPA Statement on Race & Racism’, media release, American Association of Biological Anthropologists, 27 March 2019, available at <https://physanth.org/about/position-statements/aapa-statement-race-and-racism-2019/>; and ‘ASHG Denounces Attempts to Link Genetics and Racial Supremacy’, The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 103, no. 5, 1 November 2018, p. 636, available at <https://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(18)30363-X>, both accessed 24 August 2021. Witness Peck’s selective history of ‘civilisation, colonisation and extermination’; unfortunately, this story sidesteps two telling facts. Firstly, his view of history is as old as ‘history’ itself: themes of race, slavery and genocide[20]See, for example, Thomas Figueira & Carmen Soares (eds), Ethnicity and Identity in Herodotus, Routledge, London, 2020; John Docker, The Origins of Violence: Religion, History and Genocide, Pluto Press, Norwich, UK, 2008; and Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2007. are central to Herodotus’ own story about the rise (and fall) of clashing civilisations; secondly, African nations were among history’s worst slave traders, playing an active role in the capture and trafficking of millions of Black people to foreign lands.[21]See, for example, Gad Heuman & Trevor Burnard (eds), The Routledge History of Slavery, Routledge, London & New York, 2011; and David Eltis & Stanley L Engerman (eds), The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420 – AD 1804, Cambridge University Press, New York,2011, pp. 47–163. While these ‘alternative facts’ obviously don’t invalidate Peck’s version of events, they do complicate it, and as such need to be reckoned with.

The other complication is Peck’s assumption that it is possible to reckon with history in a relatively straightforward manner. Specifically, Peck – like anyone seeking to challenge mainstream historical narratives in real time, be they white supremacist or Black Lives Matter activist – asks viewers to reframe the past via an untangling of narrative threads and navigate a way through it; yet it is this very desire for a reckoning that gives rise to competing versions of ‘history’ in the first place.

Days of reckoning

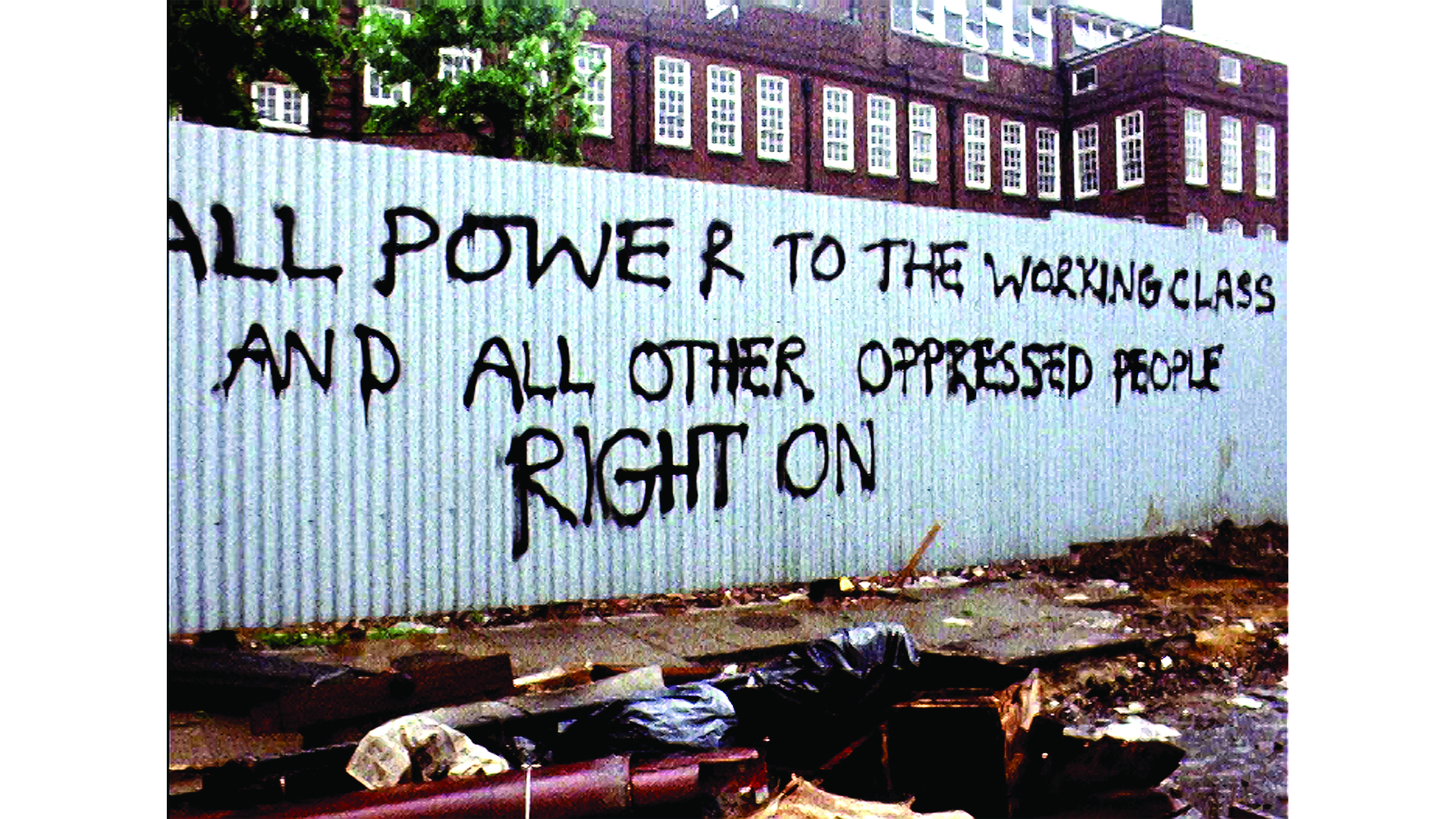

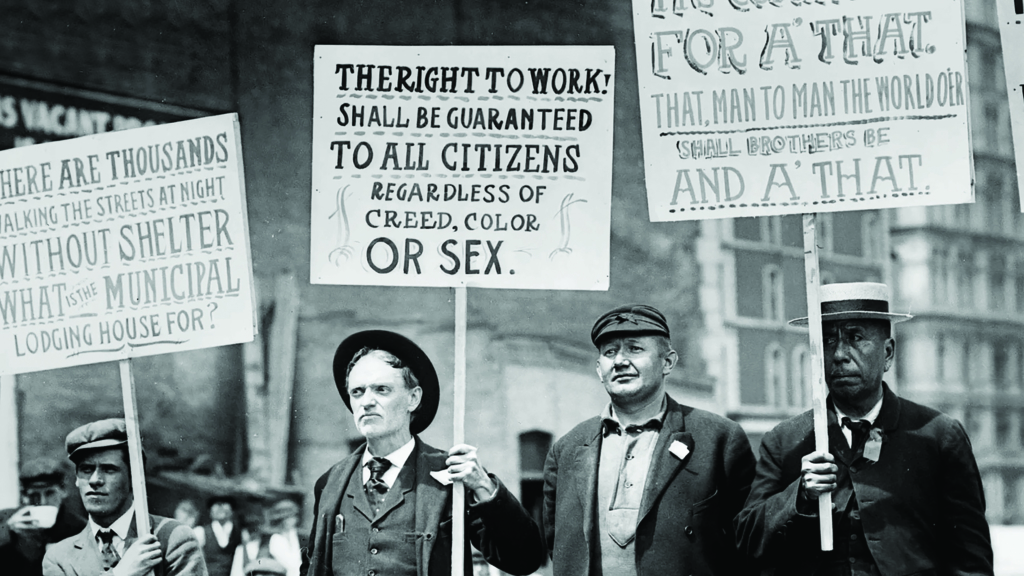

In exploring the nature of such entanglements, Can’t Get You out of My Head serves as an attempt to reckon with the very idea of history itself. ‘History’ is reframed as a potentially inescapable spectre: ‘ghosts of the past’ now haunt us all, the series argues, and cannot be exorcised from our collective memories. In this telling, instead of saving humanity from the ‘horror’ of history, the power structures of competing salvation narratives (Nazism, communism, capitalism, liberal democracy) and failed liberation movements (revolutions, terrorist activities, the Enlightenment project, public protests) have shackled us to the past and merely cast their own shadows. The ruins of memory are everywhere: concentration camps, political purges, systemic racism, structural inequalities, intergenerational traumas, mass surveillance and conspiracy theories have, Curtis asserts, since become an integral part of our personal narratives.

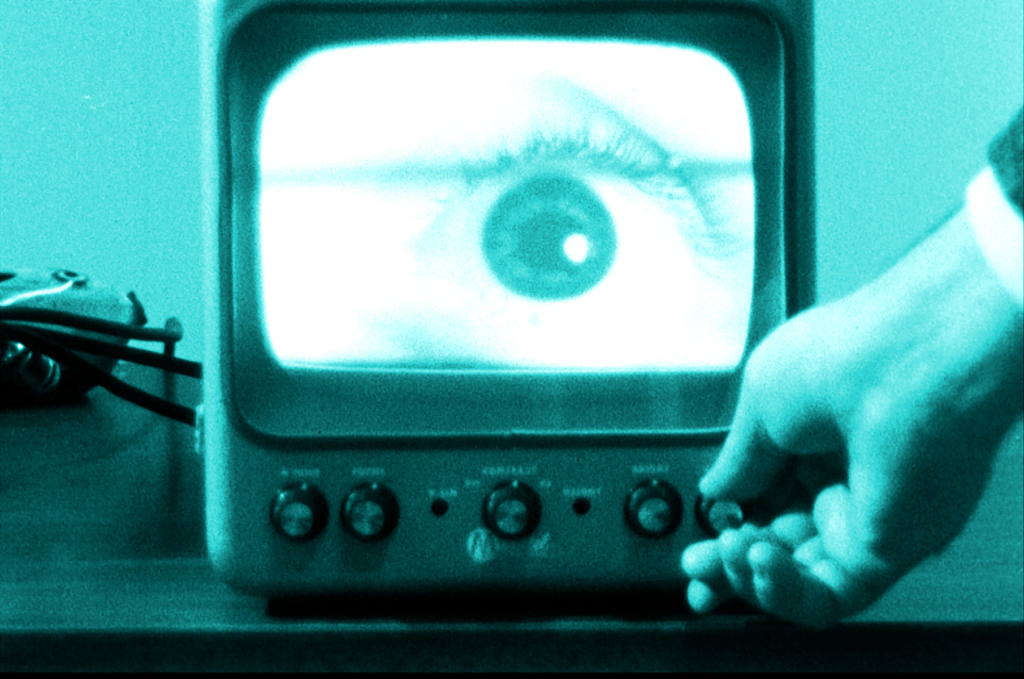

Can’t Get You out of My Head’s title therefore refers to our shared cultural inheritances, and describes a crisis of consciousness: ‘history’ itself has become a colonising force governing fragmentary inner worlds. Competing worldviews and failed ideologies all share a common narrative thread here: they have culminated in the ‘end of history’,[22]A phrase most famously employed in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War to suggest that Western liberal democracy’s triumph was absolute and permanent; see Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, 1992. For alternate perspectives predating Fukuyama’s, see Howard Williams, ‘The End of History in Hegel and Marx’, in Tony Burns & Ian Frazer (eds), The Hegel–Marx Connection, Macmillan Press, Basingstoke, UK, 2000, pp. 198–216. or delivered us into situations where real progress appears to be neither available nor possible. According to Curtis’ metanarrative, human agency, sovereignty and privacy have been taken over by technocratic management systems, media technologies, pharmaceutical corporations and market forces – all directed towards the goal of repeating (and stabilising, legitimising and exploiting) the mood states, social divisions and immediate past that have repressed us in the first place. Given this historical impasse, one possible future proposed is a return of the repressed: an unleashing of dark forces that may need to be reckoned with again.

Can’t Get You out of My Head does not proclaim that this historical dispossession of human rights and obligations is inescapable. Its reframing of the past is intended, rather, as a cautionary tale. It paves a way forward by looking back and purporting to reveal what anthropologist David Graeber describes as the ‘ultimate hidden truth of the world’: that ‘history’ can be re-created in our image.[23]This (here, partially paraphrased) quote opens the series; for the original context, see David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy, Melville House, Brooklyn, NY & London, 2015, p. 89.

Curtis reconstructs history through ‘traces’ left behind in BBC archival footage. This archaeological excavation is accompanied by portentous voiceover and sardonic musical commentary – his strategic use of the BBC’s blanket music licence arrangement[24]See ‘Archive, Rights and Clearances’, BBC Website, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/delivery/archive-rights-clearances>, accessed 24 August 2021. digs deeper than his own blanket statements. Like Peck’s approach in Exterminate All the Brutes, Curtis’ historical method relies on a seductive aesthetic of appropriation and recontextualisation. In contrast to Peck’s work, however, Curtis’ renowned use of collage can itself be traced back to his previous documentaries, and is – on the surface anyway – entirely reliant on the assemblage and juxtaposition of recovered primary sources (digitally preserved images and available musical recordings). The director has compared his cinematic technique to music ‘sampling’,[25]Adam Curtis, quoted in Michael J Brooks, ‘What Does the Future Hold? An Interview with Adam Curtis’, The Quietus, 12 February 2021, <https://thequietus.com/articles/29558-film-adam-curtis-cant-get-you-out-of-my-head-interview>, accessed 24 August 2021. and it might be useful to distinguish sampling processes to clarify the way he incorporates and reintegrates the material of Can’t Get You out of My Head. Specifically, although Curtis does not rely on statistical analysis, his historical ‘samples’ nonetheless serve the same purpose: he selects a subset of individuals to be representative of groups as a whole, and estimates their general characteristics accordingly. Curtis’ sampling technique also repurposes and/or recontextualises selected parts of past representations (images and music). The resulting remixes alter or contort the original creations to create something new in the present.

It is the idiosyncratic way that Curtis puts this emotional history together – seemingly without rhythm or reason, and typically to ironic, incongruous or bizarre effect – that provides Can’t Get You out of My Head with its narrative logic and interpretative framework. Although it might be difficult to follow the threads of his argument, we can nonetheless see him weaving together a patchwork of individuals, stories, events and moods across different spaces and times, stitching various designs and textures into a larger design or social fabric.

Although Curtis does not rely on statistical analysis, his historical ‘samples’ nonetheless serve the same purpose: he selects a subset of individuals to be representative of groups as a whole, and estimates their general characteristics accordingly.

We thereby encounter repeating patterns or surprising parallels in Can’t Get You out of My Head between Jiang Qing in Shanghai, Michael X in London, Abu Zubaydah in Guantánamo Bay, Eduard Limonov in exile, Vladimir Komarov in space, Jim Garrison in New Orleans and Tupac Shakur in Los Angeles, among others. The Tiananmen Square Massacre is woven into the same tapestry as events as diverse as the 1985 Live Aid benefit concert, Illuminati secret societies, non-majoritarian institutions, the CIA’s Project MKUltra experiments, the US opioid crisis, Boolean logic, and the convergence of data and identities.

Although the documentary series’ wideranging approach might appear arbitrary and fragmentary, its director nonetheless uses these fragments to arbitrate between opposing forces and trajectories. Curtis navigates a perceived divide between ‘the individual’ and ‘the collective’ in pursuit of finding safe passage between these two poles to reconcile opposing movements or tendencies (that is, where collective responsibility and action can still redeem or salvage individual freedoms and autonomy). World history is thus seen through the prism of individualism versus collectivism, and a dehumanising global free-market system is framed as modern slavery.

Can’t Get You out of My Head primarily explores two interlacing developments: individuals (whether they be radicals, activists or hippies) being corrupted or defeated by the power structures they set out to overturn; and elite groups (such as psychologists, scientists and economists) aligning themselves with vectors of power to ensure every individual remains an integral part of the whole corruptible system. Although we live in an age of individualism, the series concludes, our sense of individuality has been subsumed by a collectivist sensibility: specifically, wherever the ‘greater good’ – social stability and integration, cultural imperialism – has taken precedence over the welfare of individuals and communities. Curtis perceives a collective false consciousness at work here: individuals, he asserts, now live in a ‘dream world’ in which their perceptions of reality have been destabilised and normalised by technocratic mindsets and corporate interests; consequently, certain normative assumptions – freedom, autonomy, individuality – are being coopted and directed towards the nefarious end of precluding any genuine alternatives or possibilities.

Can’t Get You out of My Head’s representation of history is undermined by its idealism, and it is important to distinguish the idealisms in tension here. On the one hand, Curtis’ reconstruction commits to the metaphysical view that there is no reality independent of our perception (or construction) of it: the existence of reality is mind-dependent and literally made of shared ideas (that is, mental images) in our heads, and history would ideally be remade via the reassembling of these images into more coherent or stable sequences. Curtis’ idealism is evident in the way he reconstructs ‘history’ through existing imagery: reality is identified with selective representations of it.[26]When Curtis retrieves, say, footage of modern psychologists talking about the illusion of the self, the imputation is that psychology has constructed a real world of illusory selves. The concept of ‘self as a fiction’, however, predates modern psychology and the pathologies of capitalism. It can also be found in Buddhism and the radical empiricism of David Hume, but that doesn’t make us all Buddhists or radical empiricists! On the other hand, Curtis argues that we can only get back to reality by reclaiming those ideals, standards or principles that make the world a better, truer place. If his metanarrative is true, however, we are required to ask: By what standard or principle can we evaluate our standards or principles if they’re just in our heads and aspects of the very reality in question?

Curtis’ reconstruction of primary sources is also filtered through the lens of unacknowledged secondary sources.[27]I am not claiming plagiarism, merely that Curtis’ ‘history’ is informed by a history of ideas that he takes as given (without acknowledgment or engagement) – ideas that in many cases have become an integral part of the very culture that he sees as completely integrated. See, for example, Hazard Adams (ed.), Critical Theory Since Plato, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, CA, 1971; and Imre Szeman, Sarah Blacker & Justin Sully (eds), A Companion to Critical and Cultural Theory, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ & Chichester, UK, 2017. Can’t Get You out of My Head’s metanarrative is a patchwork of conflicting or competing ideas constituting our cultural inheritance, and thus itself symptomatic of the very cultural imperialism being diagnosed: it seizes control of distinct conceptual terrains – critical theory, post-structuralism, Weberian sociology, etc. – and colonises them with his own sensibility. Consequently, Curtis fails to acknowledge that many of his observations and concerns, while valid, are not self-evidently true or settled: they are part of a longstanding discourse that remains open to interrogation and contestation.[28]See, for example, Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Routledge, London, 1992 [1905]; Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 1994 [1930]; Jürgen Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK, 2007 [1985]; and Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Zero Books, Ropley, UK, 2009. Equally unsettling is that Curtis’ narrative logic resembles the reasoning of the conspiracy theories he openly derides in the series: his ‘sampling’ technique requires illusory pattern perception to be meaningful, because it searches for invisible threads connecting disparate people and events to reveal the ‘ultimate hidden truth of the world’. Curtis’ ‘emotional history’ thereby becomes similarly resistant to falsification and triggers ascending emotion-activating systems (confusion, paranoia, anxiety, hope and empowerment) to create an illusion of increasing control and understanding in real time. Viewers would ideally follow Curtis’ lead and regard his metanarrative’s overarching plot with equal incredulity or suspicion.

Endnotes

| 1 | Herodotus, The Histories, trans. Robin Waterfield, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 1998, p. 175. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See JAS Evans, ‘Father of History or Father of Lies; the Reputation of Herodotus’, The Classical Journal, vol. 64, no. 1, October 1968, pp. 11–7. |

| 3 | Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, Cross–curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures, 2021, p. 4, available at <https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/consultation/cross-curriculum-priorities/>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 4 | ibid. While this attempt at course correction is long overdue, some historians may question the lack of reference to genocide; see Tony Barta, ‘Decent Disposal: Australian Historians and the Recovery of Genocide’, in Dan Stone (ed.), The Historiography of Genocide, Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, UK & New York, 2008, pp. 296–322. |

| 5 | Mark Rose, quoted in Jordan Baker, ‘Students to Be Taught About “Invasion” Experience of First Nations Australians in Proposed Curriculum Changes’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 April 2021, <https://www.smh.com.au/education/students-to-be-taught-about-invasion-experience-of-first-nations-australians-in-proposed-curriculum-changes-20210429-p57nbq.html>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 6 | See, for example, James W Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, New Press, New York, 1995; and Jenny Kidd et al. (eds), Challenging History in the Museum: International Perspectives, Routledge, Abingdon, UK & New York, 2016 [2014]. |

| 7 | See, for example, Sweet Country (Warwick Thornton, 2017), The Nightingale (Jennifer Kent, 2018) and High Ground (Stephen Maxwell Johnson, 2020), all from Australia; Steve McQueen’s 2020 film collection Small Axe, from the UK; and Barry Jenkins’ 2021 series The Underground Railroad, from the US. |

| 8 | Despite its origins in Conrad’s novella, the title of Peck’s series seems to be primarily inspired by the Sven Lindqvist book of the same name, which is drawn on extensively in the series. See Lindqvist, ‘Exterminate All the Brutes’: One Man’s Odyssey into the Heart of Darkness and the Origins of European Genocide, Granta Books, London, 2018 [1996]. The two other primary sources navigating Peck’s journey into the heart of darkness are Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 1995; and Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Beacon Press, Boston, MA, 2014. |

| 9 | See ‘Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788–1930’, The Centre for 21st Century Humanities, The University of Newcastle, Australia, <https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 10 | Anthony Trollope, Australia and New Zealand: Vol. II, Bernhard Tauchnitz, Leipzig, 1873, p. 245. |

| 11 | A phrase employed by Wells in his novel The War of the Worlds in reference to the atrocities visited upon colonised peoples: ‘The Tasmanians […] were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?’ HG Wells, The War of the Worlds, William Heinemann, London, 1898, p. 5. |

| 12 | The idea that history can be objective or value-free has been challenged by post-structuralist philosophers (along with those in other disciplines such as philosophical hermeneutics). In this view, the narrative logic of ‘history’ is seen as an intellectually imperialistic enterprise: that is, stemming from a desire to seize control over inherently meaningless or chaotic events and occupy them with rational organisation and understanding. For elaborations and challenges, see Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th–century Europe, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, 2014 [1973]; Willie Thompson, Postmodernism and History, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2004; and Ewa Domańska, Encounters: Philosophy of History After Postmodernism, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, 1998. |

| 13 | Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. R Kevin Hill & Michael A Scarpitti, Penguin Random House, London, 2017, p. 287. |

| 14 | Although Peck disavows the post-structuralist and/or postmodern view of history, he nonetheless uses the term ‘deconstruct’ to describe his grand narrative. Neither Jacques Derrida nor Jean-François Lyotard would approve! |

| 15 | Mills argues that the social contract that binds us all together is a racial contract, and that it remains built on the consensual foundations of white supremacy. See Charles W Mills, The Racial Contract, Cornell University Press, New York, 1997. |

| 16 | This concept originated within fifteenth-century Spanish Catholicism. See Max S Hering Torres, María Elena Martínez & David Nirenberg (eds), Race and Blood in the Iberian World, Lit, Zürich & Berlin, 2012. |

| 17 | Originally attributed to cultural/ethnic variations (with environmental factors enabling genetic continuity and differences between cultures/regions), the modern idea of ‘race’ invariably divided humans into biologically distinct subcategories. For accounts of how the idea of race can be traced back to antiquity, see Denise McCoskey, Race: Antiquity and Its Legacy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 2012; Benjamin Isaac, The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ & Woodstock, UK, 2004; and Robert Wald Sussman, The Myth of Race: The Troubling Persistence of an Unscientific Idea, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA & London, 2014. |

| 18 | See Alex Ross, ‘How American Racism Influenced Hitler’, The New Yorker, 23 April 2018, <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/04/30/how-american-racism-influenced-hitler>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 19 | Interestingly, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists and The American Society of Human Genetics have recently (if only tacitly) disavowed science’s historical role in perpetuating the biological myth of race. See ‘AAPA Statement on Race & Racism’, media release, American Association of Biological Anthropologists, 27 March 2019, available at <https://physanth.org/about/position-statements/aapa-statement-race-and-racism-2019/>; and ‘ASHG Denounces Attempts to Link Genetics and Racial Supremacy’, The American Journal of Human Genetics, vol. 103, no. 5, 1 November 2018, p. 636, available at <https://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(18)30363-X>, both accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 20 | See, for example, Thomas Figueira & Carmen Soares (eds), Ethnicity and Identity in Herodotus, Routledge, London, 2020; John Docker, The Origins of Violence: Religion, History and Genocide, Pluto Press, Norwich, UK, 2008; and Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2007. |

| 21 | See, for example, Gad Heuman & Trevor Burnard (eds), The Routledge History of Slavery, Routledge, London & New York, 2011; and David Eltis & Stanley L Engerman (eds), The Cambridge World History of Slavery: Volume 3, AD 1420 – AD 1804, Cambridge University Press, New York,2011, pp. 47–163. |

| 22 | A phrase most famously employed in the immediate aftermath of the Cold War to suggest that Western liberal democracy’s triumph was absolute and permanent; see Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, 1992. For alternate perspectives predating Fukuyama’s, see Howard Williams, ‘The End of History in Hegel and Marx’, in Tony Burns & Ian Frazer (eds), The Hegel–Marx Connection, Macmillan Press, Basingstoke, UK, 2000, pp. 198–216. |

| 23 | This (here, partially paraphrased) quote opens the series; for the original context, see David Graeber, The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy, Melville House, Brooklyn, NY & London, 2015, p. 89. |

| 24 | See ‘Archive, Rights and Clearances’, BBC Website, <https://www.bbc.co.uk/delivery/archive-rights-clearances>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 25 | Adam Curtis, quoted in Michael J Brooks, ‘What Does the Future Hold? An Interview with Adam Curtis’, The Quietus, 12 February 2021, <https://thequietus.com/articles/29558-film-adam-curtis-cant-get-you-out-of-my-head-interview>, accessed 24 August 2021. |

| 26 | When Curtis retrieves, say, footage of modern psychologists talking about the illusion of the self, the imputation is that psychology has constructed a real world of illusory selves. The concept of ‘self as a fiction’, however, predates modern psychology and the pathologies of capitalism. It can also be found in Buddhism and the radical empiricism of David Hume, but that doesn’t make us all Buddhists or radical empiricists! |

| 27 | I am not claiming plagiarism, merely that Curtis’ ‘history’ is informed by a history of ideas that he takes as given (without acknowledgment or engagement) – ideas that in many cases have become an integral part of the very culture that he sees as completely integrated. See, for example, Hazard Adams (ed.), Critical Theory Since Plato, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, San Diego, CA, 1971; and Imre Szeman, Sarah Blacker & Justin Sully (eds), A Companion to Critical and Cultural Theory, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ & Chichester, UK, 2017. |

| 28 | See, for example, Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Routledge, London, 1992 [1905]; Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents, Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 1994 [1930]; Jürgen Habermas, The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity: Twelve Lectures, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK, 2007 [1985]; and Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?, Zero Books, Ropley, UK, 2009. |