THE NFSA RESTORES COLLECTION: PART 56

I must narrow down to some degree what I mean by ‘committed documentary.’ […] By ‘commitment’ I mean, first, a specific ideological undertaking, a declaration of solidarity with the goal of radical sociopolitical transformation. Second, I mean a specific political positioning: activism, or intervention in the process of change itself […] Filmmakers on the Left have always realized that film, like all cultural forms, is a bearer of ideology.

– Thomas Waugh[1]Thomas Waugh, ‘Why Documentary Filmmakers Keep Trying to Change the World, or Why People Changing the World Keep Making Documentaries’, in Waugh, The Right to Play Oneself: Looking Back on Documentary Film, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis & London, 2011, p. 6.

The intense involvement and interaction between a film-maker and the subject of their film was a common practice of activist documentary-makers during the 1970s and early 1980s. It was a critical relationship, which guided the narrative and informed the film’s ideology, mode of film-making, and aesthetic.

– Kathy [2]Kathy Sport, ‘Save Our Homes: Activist Documentaries 1970–1985’, Metro, no. 136, 2003, p. 142.

Released thirty-seven years ago, the feature documentary Rocking the Foundations (Pat Fiske, 1985) created an immediate impact and firmly established its writer/director/producer as a major filmmaker in the non-fiction sector.[3]For a comprehensive overview of Fiske’s career, see Tina Kaufman & Gillian Leahy, ‘Interview with Pat Fiske’, Metro, no. 127/128, 2001, pp. 64–75; and ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske: OzDox Nov 2019’, YouTube, 11 February 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1WiwF1DEEs>, accessed 10 March 2022. Nominated for Best Documentary at the 1986 Australian Film Institute Awards, the film ended up winning the non-fiction category’s screenplay and editing prizes. In the year following its Australian release, Fiske travelled abroad to present the film at the USA and Edinburgh film festivals.

According to its distributor, Ronin Films, Rocking the Foundations has been in constant demand for three decades, and has long enjoyed a profit.[4]Author interview with Andrew Pike, 30 December 2021. It is regularly taught in schools and universities and often screened at festivals and conferences. Applauded for its political courage, the documentary was seen among peers as something of a breakthrough: here was a film fermented in activist politics, feminist practice and social-democratic principles and made on its own terms touching the mainstream (though not, as it turns out, without controversy).[5]See Susan Lambert, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/rocking-the-foundations/notes/>; and Sylvia Lawson, ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, Inside Story, 30 October 2014, <https://insidestory.org.au/documentary-just-call-it-cinema/>, both accessed 10 March 2022.

Though it received institutional financial support, Rocking the Foundations was a project that emerged from the margins of independent filmmaking in the 1970s. Its protracted, complex production history was typical of so many pictures of its kind. Filmmakers like Fiske could spend years working without fees and with few resources, pouring their own earnings into a picture in order to bring it to completion and relying on friends, family and a community of like-minded movie makers for material and (often) moral support.[6]Official estimates published in 1985 put the final budget at A$150,000; Fiske today believes that its true cost is difficult to nail down. Encore reported the funding breakdown as A$119,000 from the Australian Film Commission (AFC), A$20,000 from the AFC’s Project Branch, A$5000 from Sydney City Council and A$4000 from the Music Board (Art and Working Life Project). See ‘Documentaries: BLF History Goes Down on Film’, Encore, 21 November – 4 December 1985, p. 37.

Rocking the Foundations has the surface presence of popular documentary technique seen in works like Rob Epstein’s The Times of Harvey Milk (1984) – a film that Fiske says was an influence – including a strong sense of narrative, testimony from talking heads directly involved with the subject, an intimate voiceover, prominent use of music, and a self-consciously assertive confidence in the importance of the story being told.

However, it’s characteristic of discussions on Fiske’s film to focus on its content and not its style. This is to be expected, since it engages with such subject areas as the tensions between community and modernity, environment and urban development, labour and capital, workers and the wider society and culture, and women in the workforce and those who would oppose their presence. Still, in setting out to tell the story of an innovative union, Rocking the Foundations interlaces documentary style in a way that makes it unique. In what follows, I have tried to both capture the materiality of the film and convey how Fiske and her colleagues shaped their convictions into sound and image.[7]For a detailed discussion of the various ‘modes of documentary’ at work in Rocking the Foundations, see Sport, op. cit., pp. 138–46.

An uncompromising stance

When Rocking the Foundations premiered in Sydney at the Chauvel Cinema in November 1985, critical reception was positive without exception. Matt White’s review in Sydney tabloid afternoon newspaper Daily Mirror was typical, referring to Fiske’s film as ‘passionate’ and ‘heroic’;[8]Matt White, ‘Pat’s Labour of Love for BLF Rocks City’s Soul’, Daily Mirror, 19 November 1985. fellow tabloid The Daily Telegraph told readers it was ‘fascinating’ and ‘burned with sincerity’;[9]‘Passionate Tribute’, The Daily Telegraph, 22 November 1985. and John Hanrahan in The Sun said the film was ‘provocative’ and ‘quite an education’.[10]John Hanrahan, ‘Rocking the Foundations!’, The Sun, 21 November 1985. Susie Eisenhuth in The Sun-Herald believed the film ‘timely and well worth a look’,[11]Susie Eisenhuth, ‘Heroes of the BLF – of Yesteryear, That Is’, The Sun-Herald, 17 November 1985. while The Catholic Weekly described it as ‘a sound piece of social realism’.[12]‘Greenies Versus Gallagher’, The Catholic Weekly, 11 December 1985.

On reflection, however, the enthusiasm in these pieces – and in most other critiques published in mainstream outlets – is highly qualified. The reviews are filled with an air of caution as much as a frank admiration for the skill in the filmmaking, which could be read as an unease with the core subject matter and the tone of the film itself. This is because – and most of the reviews are direct about this – Rocking the Foundations is a story of a union and, specifically, union militancy. Most reviewers were aware that this documentary feature had grown out of a subculture of activism: that is, the film was not detached, balanced reportage, but a ‘minority’ view. It was personal filmmaking – as much an essay film, even a memoir, as it was a kind of history. It was told from the point of view of an insider, and its politics are unapologetically partisan; its aim, transparently didactic. Indeed, for most of the filmmakers involved, that was the point.[13]As per author interviews with Martha Ansara, Fabio Cavadini and Pat Fiske in December 2021. All unattributed quotes in this essay are sourced from these interviews. Almost all of the characters interviewed in the film and seen in archival footage found their political allegiance on the far left, and they speak firsthand about their struggles and commitment. Hanrahan put all of this into perspective in his review: ‘Naturally, your place on the political spectrum will no doubt colour your attitude to the film.’

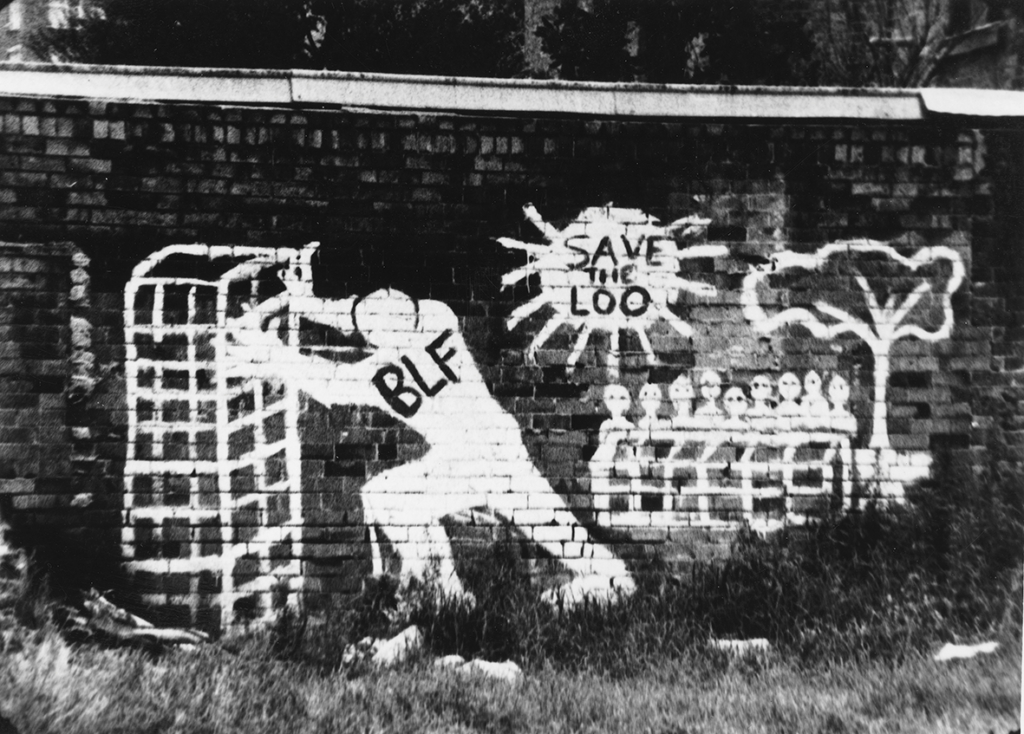

Rocking the Foundations’ head credit includes the explanatory title ‘a history of the New South Wales Builders Laborers[14]Although this might seem to be an error, the divergent spelling and punctuation of the NSWBLF’s name in this subtitle is reflective of the union’s inconsistent rendering of it over the years in its own materials. See Meredith Burgmann & Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: The Saving of a City, revised edn, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2017 [1998], p. xxi. Federation, 1940–1974’. That timeline was significant to how the film would be understood. Fiske (who shared editing duties on the film with Stewart Young and Jim Stevens) had elected to focus half of Rocking the Foundations on the green bans era of the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation (NSWBLF), which lasted from 1971 to 1974. This was a period of community activism and direct action, in which the rank and file of the union joined with residents and their allies to save large areas of Sydney – parks, wildlife, old buildings, entire neighbourhoods – from the threat of destruction. According to labour historians, the actions and policies of the NSWBLF in this era were a ‘world first’.[15]Meredith Burgmann, ‘Valé Jack Mundey: The Builders Labourers’ Leader Who Saved Glebe’, The Glebe Society website, 6 June 2020, <https://glebesociety.org.au/vale-jack-mundey-the-builders-labourers-leader-who-saved-glebe/>, accessed 9 March 2022. For a comprehensive account of the period covered in Rocking the Foundations, see Burgmann & Burgmann, ibid. It’s worth noting that Meredith Burgmann and Fiske exchanged research in order to assist each other’s project. This was one of the drivers for Fiske and her team, and it helps to explain the film’s celebratory tone.

But the old NSWBLF – together with its leadership and sensibility – was long gone by 1985. For many, so was the era of protest, even if new movements had arisen to meet fresh challenges.[16]For instance, there was tremendous anxiety over the build-up of nuclear weapons; some of this protest is detailed in Midnight Oil: 1984 (Ray Argall, 2018); see Cavan Gallagher, ‘Power and the Personality: Ray Argall’s Midnight Oil: 1984’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 86–9. The time of the green bans had ended in scandal, and the national Builders Labourers’ Federation (BLF) of 1985 was on the nose. Less than a week after Rocking the Foundations opened in Sydney, The Age ran a story entitled ‘A Union Becomes an Industrial Outcast’. The BLF was facing deregistration amid rumours of corruption and bribery, with its national secretary, Norm Gallagher, at the centre of the controversy.[17]See Paul Robinson & Brendan Donohoe, ‘A Union Becomes an Industrial Outcast’, The Age, 27 November 1985, p. 1. ‘Big Norm is by no means the hero in this documentary,’ Eisenhuth pointed out. ‘You’re not exactly asked to hiss the villain but it’s a near thing [… The NSWBLF] in this movie are the goodies.’[18]Eisenhuth, op. cit.

This notion of partisanship was picked up in the left-wing print media too, and it was used to mobilise contested turf, old disputes and present anxieties felt in progressive circles. ‘In today’s climate when the “BLF” is more likely to be seen as a blot on unionism,’ wrote David McKnight in Tribune, ‘it is worth seeing this film to realise that unions are not automatically confined to winning support from their members alone but can win wide community support.’[19]David McKnight, ‘Rocking the Foundations – How the NSWBLF Changed Unionism’, Tribune, 20 November 1985. McKnight ended his review on a note of nostalgia, suggesting that the film would bring a surge of emotion to all who had been part of the green bans. Writing in Direct Action, Robyn Marshall called Rocking the Foundations a ‘great movie, except for the ending’. Accusing the filmmakers of being emotionally locked into ‘the Mundey–Owens era’, Marshall complains that the film demonises Gallagher at the expense of history.[20]Robyn Marshall, Rocking the Foundations review, Direct Action, November 1985.

Fiske, like most independent documentary filmmakers before and since, took a hands-on approach in promoting the film, with the support of the Australian Film Institute (AFI).[21]Fiske credits Helen Zilko at the AFI for much of the marketing push on Rocking the Foundations. Completing it in August 1985 after years of post-production, she was interviewed widely by a media eager to press her on questions regarding Gallagher’s legitimacy.

Experienced in ‘street politics’ and no fan of the BLF leadership, Fiske deftly negotiated the risks involved in pitching the film to a sceptical media. Audiences for documentaries in theatres were traditionally small; in the mid 1980s, two-week seasons booked into art houses were customary.[22]David Bradbury’s Chile: Hasta Cuando? (1986) played to an audience of 6500 in its Melbourne season, he claimed; see Craig McGregor, ‘Is the Documentary Dying? Long Live Radicalism’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 May 1986. Here was a film that would at first glance seem to preach to the converted, as many writers claimed – and, not only that, involved the arcane intricacies of industrial relations. Yet, in interviews, Fiske carefully framed the story as universal, emphasising its idealism along with values like collective responsibility, where barriers of prejudice and fear based on status, class, race, sexuality and gender can give way to a shared goal. ‘People don’t have to take what’s given; they can have control over their lives and rise up,’ Fiske told The Sun in December 1985.[23]Pat Fiske, quoted in Debbie Coffey, ‘The City’s Threatened Again …’, The Sun-Herald, 1 December 1985.

Strength in solidarity

As the film details, between 1971 and 1974 the NSWBLF had taken a major role in confronting social issues head-on. The war in Vietnam, apartheid in South Africa, gay rights, women’s liberation and Indigenous land rights became important policy issues to the workers as much as the traditional bread-and-butter union obligations such as wages, hours and conditions. According to Fiske, Rocking the Foundations demonstrated how a union can and could ‘accelerate social change in the world’.[24]ibid.

The radicalisation of the union and the impact of this on the wider world is Rocking the Foundations’ core narrative driver. The film sums up the motivations, social forces, personalities and specific circumstances that altered the character of the NSWBLF. A key influence was class solidarity; by the virtue of their jobs, union members had been asked to tear down the homes of working-class people. Moral objections to this merged with a rising consciousness in support of the green movement: ‘The power of labour to protect the environment,’ write Meredith and Verity Burgmann in their history Green Bans, Red Union: The Saving of a City, ‘is commonly discounted [decades later] in discussing ecological problems.’[25]See Burgmann & Burgmann, op. cit., p. xiii.

Coincidentally, in the spring of 1985, Sydney was facing a string of large-scale projects. These developments, too, had vocal critics – it all seemed an echo of the green ban battles from a decade earlier. Fiske seized upon this situation to make the point that Rocking the Foundations was more ‘living history’ than it was a paean for veterans of protest (and many of those sites they fought for are listed as endangered in the film’s closing titles).

In the spring of 1985, Sydney was facing a string of large-scale projects … Fiske seized upon this situation to make the point that Rocking the Foundations was more ‘living history’ than it was a paean for veterans of protest.

Fiske and the AFI were eager to land airtime on broadcast network TV, which they saw as an ideal way to bolster the film’s chances at the box office (and promote its message). Rocking the Foundations was shown to executives and producers of current affairs programs at the ABC and Channel Nine in Sydney, but nothing came of either opportunity. Correspondence between the involved parties in the production’s archives indicate, in both instances, that political sensitivities – as much as casual assumptions over target demographics – may have played a role in the outcome.

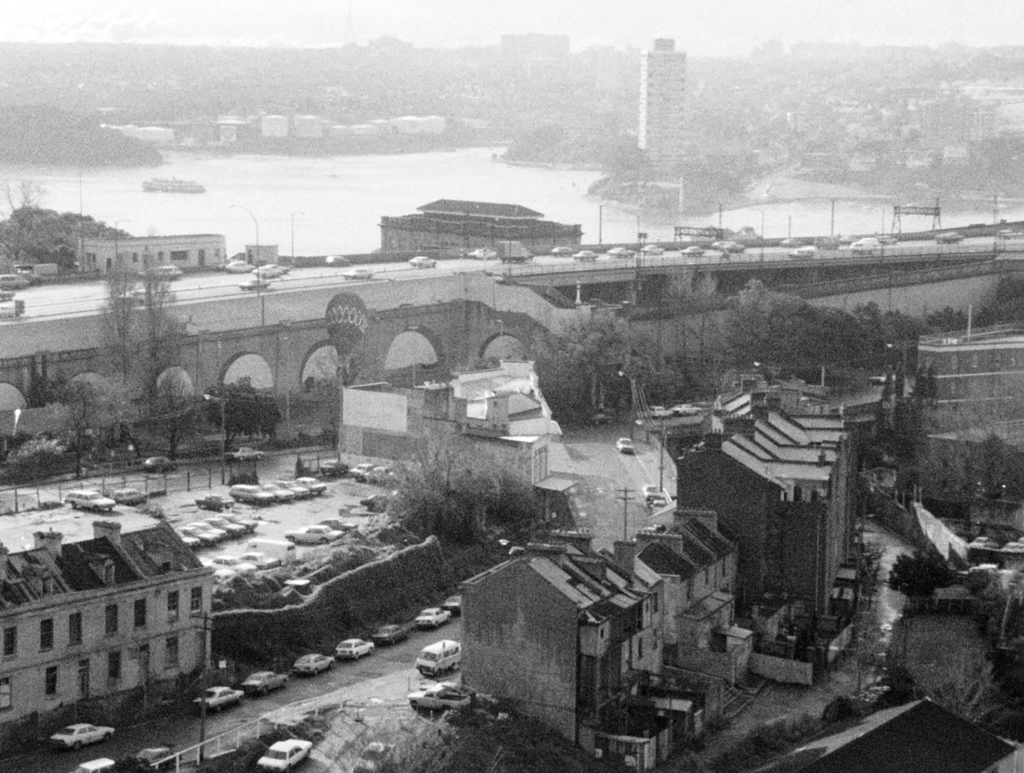

It should be pointed out, in this context, that the green bans and the NSWBLF’s role in them were a national news story.[26]See ‘Newscuttings Regarding Film Rocking the Foundations’, in manuscript collection of Australian Building Construction Employees’ and Builder’s Labourers’ Federation New South Wales Branch, MLMSS 4879 / Box MLK4272 / Item [19], State Library of New South Wales. Fiske is mystified as to how this material ended up in this collection! One episode especially – extensively detailed in Fiske’s film – had become an infamous tabloid ‘event’: the struggle over Victoria Street in the suburb of Kings Cross. Traditionally, it was a low-income area, ‘inhabited by wharfies, sailors, artists, single people and families’, with most of the dwellings dated from the mid nineteenth century. A high-rise development in the street and in neighbouring Woolloomooloo would displace thousands if successful. Resident action groups were formed, and the NSWBLF imposed a green ban; essentially, this was a stop-work order to members. By mid 1973, this kind of action by the NSWBLF had succeeded in preventing close to A$3 billion worth of construction-related activity from moving forward in the city; there were more than thirty green bans in total.

This inspired a violent reaction. One leader of the Victoria Street protest, Arthur King, was kidnapped; he was released after three days and subsequently left the area. Juanita Nielsen, who lived at 202 Victoria Street, started independent newspaper NOW and used it to muster opposition to the real estate prospector behind the project, Frank Theeman. She disappeared in 1975; when some of her personal effects were discovered on a country highway outside the city, many assumed that she had been murdered. (This section, incidentally, is one of the few chronological breaks Fiske allows, as the green ban era ended before the Victoria Street conflict found its tragic climax.)

By 1985, the events around Victoria Street had been fictionalised in two feature films, The Killing of Angel Street (Donald Crombie, 1981) and Heatwave (Phillip Noyce, 1982). Neither film was a success. In the years since, stories have emerged from the filmmakers involved that the two productions experienced intimidation.[27]See Anthony Buckley, Behind a Velvet Light Trap: A Filmmaker’s Journey from Cinesound to Cannes, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 223–34; and Ingo Petzke, Phillip Noyce: Backroads to Hollywood, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2004, p. 108. Nielsen has long been the subject of books, TV documentaries and radio specials – most recently, a two-part TV series directed by Kriv Stenders, Juanita: A Family Mystery (2021), which was released alongside an accompanying ABC podcast. It was David Stratton in Variety who was the first to make the link between these pictures and Fiske’s film, which he called, without irony, ‘the stuff of a Frank Capra movie’.[28]David Stratton, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Variety, 23 October 1985. The AFI and Fiske liked this line so much that they used it on the poster.

In March 1975, 2000 people crowded into the Sydney Town Hall. Most were unionists and their supporters, many card-carrying members of the 11,000 strong NSWBLF. At this point, the union was in turmoil, facing destruction. All wanted to hear the official line on how best to deal with the crisis. A week earlier, its offices had been burgled; its membership files, stolen. It was widely suspected that the culprits were supporters of the union’s federal body and acting on orders from Gallagher, who believed that the current leadership of the NSWBLF had led the rank and file to risk their independence – at one point dismissing the branch’s policies as being the objectives of ‘residents, sheilas and poofters’.[29]Norm Gallagher, quoted in Burgmann & Burgmann, op. cit., p. 54.

Gallagher had set up a rival union and gathered the support of the conservative state government, along with stakeholders in the building industry. The BLF was looking at deregistration. The Town Hall meeting ended in cheers and tears when the leadership of Bob Pringle, Joe Owens and Jack Mundey told the crowd they would stand down and ‘fight from within’. As they left the stage, the meeting gave them a ten-minute standing ovation.[30]Burgmann & Burgmann, ibid., pp. 273–4. None of this trio would ever work in the industry again. This moment emboldened Fiske, who was in attendance at the meeting and already deep into working on a documentary that would lay the groundwork for Rocking the Foundations.

Labour and the women’s movement

The roots of Rocking the Foundations, Fiske says, are inevitably intertwined with the facts of her life, her social and cultural experiences, and her introduction to filmmaking.

Born into a Catholic family in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1946, Fiske describes her childhood as working-class, conservative but imprinted with a ‘strong sense of social justice’. Her induction into political activism came when protesting the Vietnam War in the late 1960s: ‘I was not then a feminist,’ she says, but adds that that changed after she arrived in Australia in 1972.

Trained as a speech therapist, Fiske quickly found that her qualifications were not recognised in Australia. Settling in Sydney, she moved into a communal house in the inner-city suburb of Camperdown, where one of the women living there introduced her to still photography. Another housemate, Janne Reid, worked as a builder’s labourer. All of these women and their circle of friends were in some way engaged with the women’s movement.

Transformation – personal, political and social – is a major theme in Rocking the Foundations. In the film, Fiske remembers this period by merging her lived reality with historical context, including the arrival of Australia’s first (and, to date, only) social democratic government in 1972, in which the ALP, led by Gough Whitlam, displaced conservative rule for the first time in twenty-three years. Fiske’s film is rarely discussed as poetic – it is routinely and dismissively thought of as ‘down-to-earth’[31]See, for example, Tony Mitchell, ‘Rock Solid: Rocking the Foundations’, Cinema Papers, no. 55, January 1986, p. 63. – but this moment is typical of the film’s expressive use of archival material, voiceover and music. With the famous ‘It’s Time’ election song blaring on the soundtrack, we see Whitlam in a spotlight, striding onto a stage, towering over a crowd of gaga supporters.

‘Bold and immediate reforms began both at home and abroad,’ Fiske explains in a narration she performs herself:

Authority, custom, traditional roles: all were in transition. Women’s liberation was challenging male domination, prejudice, the exclusive right of men to work even in the most macho of industries. Women would have found it impossible to get jobs without union support. It became official policy to encourage them into the workforce.

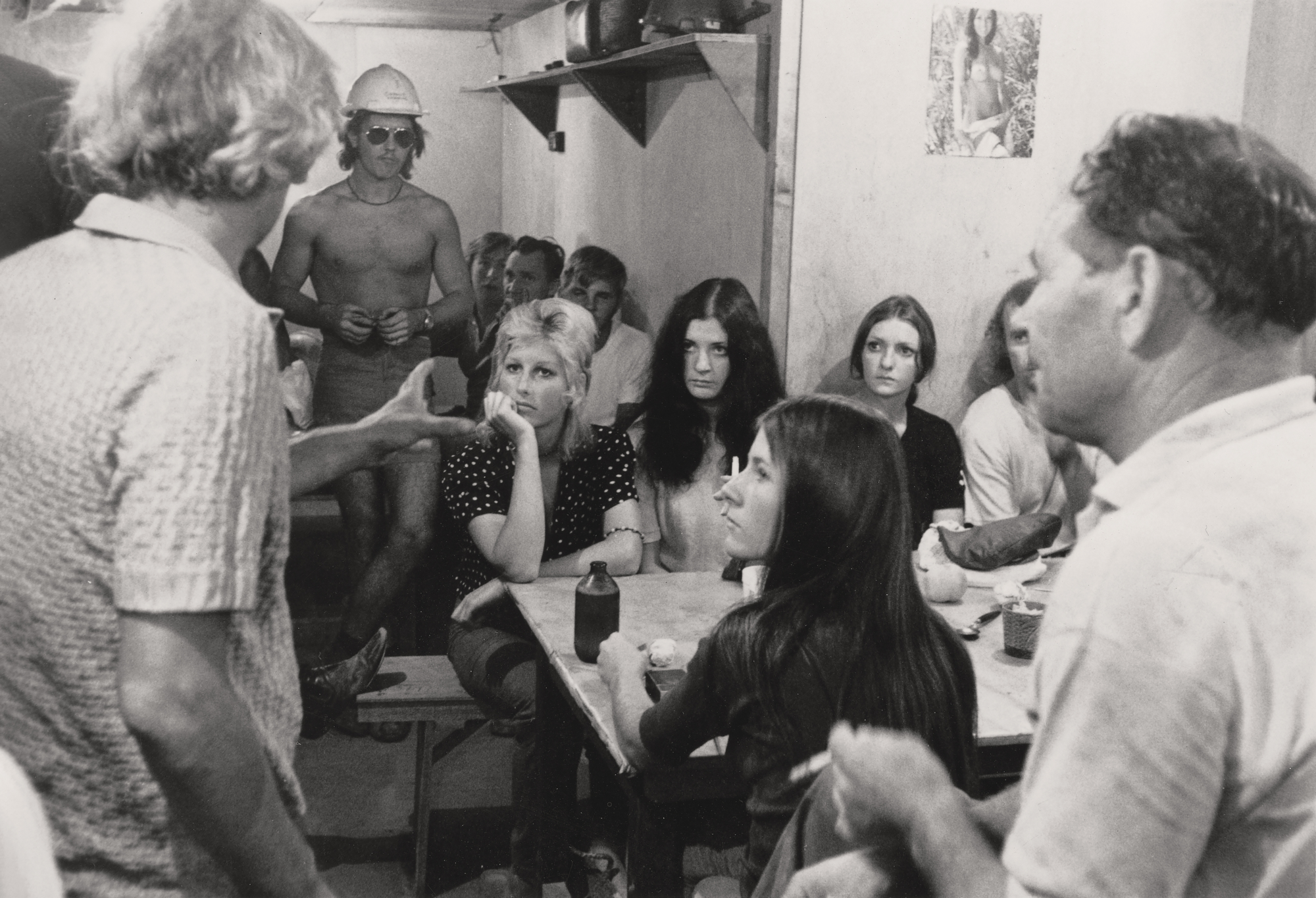

Accompanying these words is a montage of newsreel footage and still photos: women in hard hats; women at protests and participating in meetings (Germaine Greer appears in one shot); women on building sites, sometimes side by side with men. Within this passage, Fiske includes a snapshot of herself, her long hair in plaits, eating a sandwich on a building site, her mouth full: ‘It was during this time that I became a builder’s labourer,’ she deadpans.

By early 1975, there were approximately eighty women working as builder’s labourers in New South Wales. But the practice, as Fiske explains in the film, was contentious for builders, employers and fellow male labourers and tradespeople. It was certainly a culture shock. Today, Fiske recalls that there were clashes of sensibility, especially regarding overt sexism. ‘The men would whistle at women [passers-by],’ she remembers. ‘I would race across the site and kick them up the bum and scream at them, “You can’t do that!”’

Fiske challenged another practice: lunchtimes on building sites were known for film screenings, with pornography the viewing of choice. Fiske thought she could ‘do better’. With a borrowed projector, she screened documentary films that she thought the workers might appreciate; a popular choice was Attica (Cindy Firestone, 1974). Fiske had accessed both projector and prints from an organisation that had led her directly into filmmaking: the Sydney Filmmakers Co-operative (SFC).

A ‘screen education’: Fiske and the Sydney Filmmakers Co-operative

As scholars have long observed, the filmmaker co-ops that emerged in Australia’s capital cities over fifty years ago made a crucial contribution to local (and international) cinema. While space does not allow any detailed discussion of their history here, it is not possible to tell the story of the making of Rocking the Foundations without noting the influence of the SFC on Fiske and, ultimately, the character and aesthetic of the film itself.

Filmmaker John Hughes describes how co-ops were part of a global phenomenon: one that, he writes, was ‘born out of necessity – both economic and political’.[32]John Hughes, ‘A Work in Progress: The Rise and Fall of Australian Filmmakers Co-operatives, 1966–86’, Senses of Cinema, no. 77, December 2015, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/australian-film-history/australian-filmmakers-co-operatives/>, accessed 10 March 2022. Before Australia’s feature film revival, the majority of film workers were engaged in industrials (that is, corporate-sponsored non-fiction), advertising and news gathering. Some were employed by the ABC and the Commonwealth Film Unit, while a small cohort were engaged in locally produced TV drama (a sector still very much in its infancy at the end of the 1960s).

It is not possible to tell the story of the making of Rocking the Foundations without noting the influence of the Sydney Filmmakers Co-operative on Fiske and, ultimately, the character and aesthetic of the film itself.

‘A lot of the people who worked those jobs wanted to make a very different kind of film,’ recalls filmmaker and then–SFC member Martha Ansara. These individuals, she says, included Kit Guyatt (director of 1967 documentary President Johnson’s Visit), Tom Cowan (director of 1972 feature The Office Picnic) and Albie Thoms, the co-founder of SFC forerunner Ubu Films. These and others engaged in what might be called personal, committed, innovative production activity in the years that followed. They created a corpus of work that was often controversial, even with fellow members of their loose cohort; disputes arose over aesthetics, objectives and modes of production. ‘The SFC was our film school,’ recalls filmmaker Tom Zubrycki. ‘There were conflicting agendas: men vs women; social-action film vs experimental […]’[33]Tom Zubrycki, in ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske’, op. cit. Still, as Hughes puts it, what the SFC filmmakers had in common was that the work they made was ‘unwelcome’ in public broadcasting and commercial distribution. The co-ops provided a distribution network and outlet that would help grow an audience for what might broadly be called the avant-garde. In the co-op culture, values like authenticity, creativity and cooperation were set up to offer an alternative to those that Hughes characterises as dominant in the ‘straight’ culture of the 1970s and early 1980s: ‘authoritarianism, alienation and avarice’.[34]Hughes, op. cit.

Traditionally – notoriously, even – distribution and exhibition has been split in Australia from the means of production to the inevitable disadvantage of the filmmakers involved. The co-op, by contrast, provided a democratic collectivist model, an opportunity for emerging filmmakers to develop a distribution and exhibition ‘front’ that they had control over.[35]Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines, Bernt Porridge, Shenton Park, WA, 2001, p. 91. For an excellent account of the SFC, see pp. 89–100 of this book.

By the time Fiske became involved in the SFC, the organisation was headquartered in St. Peters Lane, Darlinghurst (not far from Victoria Street). It featured a small basement cinema with about 100 seats where films were screened in 16mm, often grouped into seasons around a theme or aesthetic practice – Aboriginal activism, feminist issues or gay rights, for instance. It was anti-hierarchical, an aspiration reflected in the minutiae of its social history, which is filled with anecdotes about now-prominent film industry figures jumping in to make curtains or paint walls to create a serviceable venue. In 1973, the year Fiske first encountered the SFC, the organisation boasted 133 members and had more than seventy films in distribution. By the time it finally closed its doors in 1986, the SFC had a catalogue of 325 films, including work by Jon Jost, Maya Deren, Jonas Mekas and Yoko Ono. For more than a decade, the SFC demonstrated to the trade, the film agencies and the public that there was, after all, a market for shorts and documentary cinema.[36]Filmmakers received 50 per cent of rentals and 75 per cent of print sales; see Sylvia Lawson, ‘Does the Film Co-op Deserve to be Saved?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 January 1986. The wording I use here is paraphrased from filmmaker Margot Nash, quoted in Hughes, op. cit.

It was here that Fiske – who, by her own account, had never previously been a cinephile – received a ‘screen education’; she became one of the regular projectionists at the SFC, and it was there that she first saw two documentary films involving labour relations and women in the workforce that became important influences on Rocking the Foundations: The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter (Connie Field, 1980) and With Babies and Banners: Story of the Women’s Emergency Brigade (Lorraine Gray, 1979).

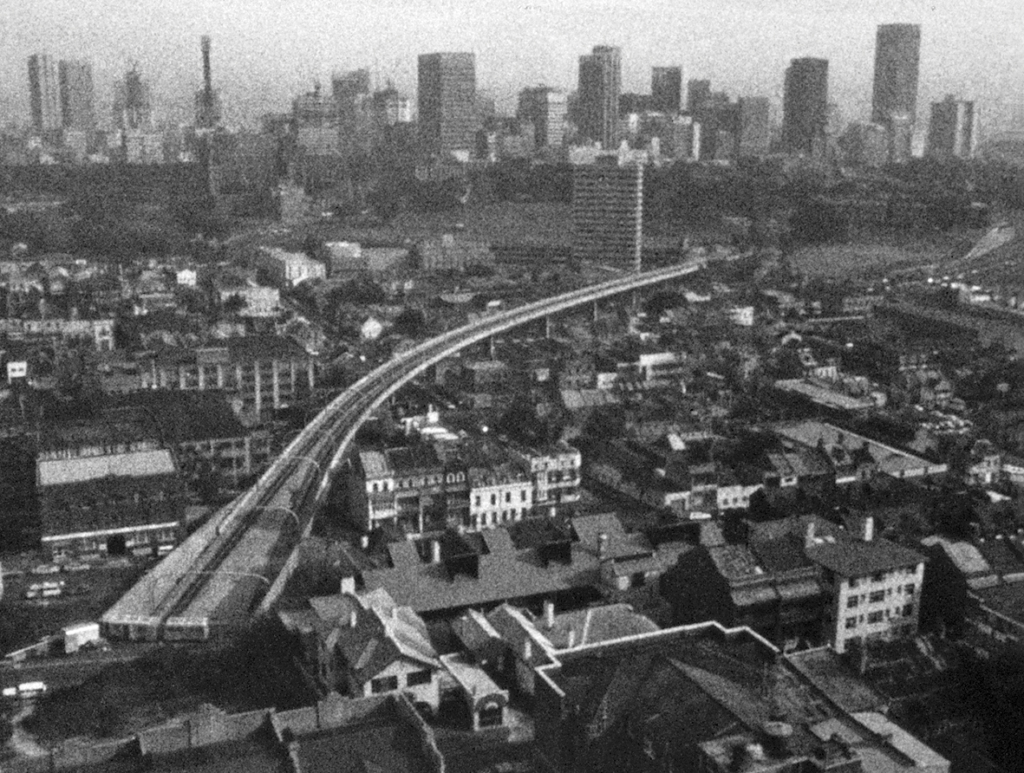

Fiske first got involved with filmmaking in 1973, when she paid A$50 and signed up for a nine-week 16mm workshop, dubbed ‘Blinky Bill’,[37]According to Fiske, Matt Butler, who delivered the workshop, called it ‘Blinky Bill’ because he found the character non-threatening, unmistakably Australian (‘dinky-di’, he says) and, happily, out of copyright. run by the SFC out of Ansara’s home. Out of this came a four-minute short, Burstforth (1973), an experimental documentary Fiske wrote, edited, produced and directed about the city being overwhelmed by nature. Among the women in the workshop was Denise White, who had friends squatting in Victoria Street. ‘At the time […] there was a lot of uncontrolled redevelopment going on in Sydney,’ White recalled in an interview with Cinema Papers in 1979. ‘There were so many cavities, the city was like a mouth with all its teeth knocked out.’[38]Denise White, quoted in Barbara Alysen, ‘Filming the Green Bans: 1. Woolloomooloo 2. Green City’, Cinema Papers, March/April 1979, p. 276.

Fiske joined White in the campaign to save Victoria Street, an experience that both women were deeply moved by. ‘The green bans were unique,’ Fiske told Cinema Papers. ‘Something I had never heard of before. Unions in the U.S. are very weak and don’t have much impact.’[39]Pat Fiske, quoted in Alysen, ibid., p. 276. As the conflict between the federal BLF led by Gallagher and the NSW branch was reaching its climax, she took a camera to the protest and filmed some of it.

Woolloomooloo: A precursor

By late 1974, White and Fiske had agreed to make a documentary about the NSWBLF. They began with a small grant of A$3000 from the Australian Film Commission, and envisaged a production timeline of a year; ultimately costing A$16,000, the final 75-minute film, Woolloomooloo (Fiske, White & Peter Gailey, 1978), was made with ‘volunteer labour’.[40]Fiske says that estimates are unreliable. For instance, the figure of A$13,000 has been quoted elsewhere. See Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 67.

According to published accounts, editing on this film did not begin until early 1977[41]See, for example, Alysen, op. cit. (today, Fiske revises this and believes post-production started earlier). The footage and structural design of the narrative at that nascent stage became split between telling the NSWBLF story and that of the green bans action of 1973–1974. As they did not have much experience editing at that stage, Fiske and White brought in Gailey – who had shot some Victoria Street protest footage – to work on the cut. The NSWBLF storyline and the footage relating to it was shelved, with the trio electing to focus instead on the events surrounding the plan to demolish large sections of the Woolloomooloo basin, including Victoria Street, in order to make way first for a freeway, then a high-rise project. As White explained soon after Woolloomooloo was released, the idea was to deliver ‘a chronological film where people could follow the story, but where those involved told it. That meant using as little narration as possible.’[42]White, quoted in Alysen, ibid., p. 279. Emphasis added.

In Fiske’s colourful phrasing, Woolloomooloo is ‘as rough as guts’.[43]Fiske, quoted in Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 67. Here, ‘rough’ might mean that the film does not follow certain conventions of craft and style. The framing is loose, and often the camera wobbles in an attempt to follow an unanticipated action. The black-and-white footage looks grubby. Boom mics and crew members are often seen in the same frame as participants. Those being filmed engage with crew on camera in spontaneous dialogue, sometimes without a cut.

‘Content is given priority over style’ in an ‘information-heavy’ film like Woolloomooloo, Sport observes, ‘and style is found on location.’[44]Sport, op. cit., p. 144. This is a fair assumption, but style was a function as much of ideology – strong within the SFC – as production contingencies. The aim was authenticity: the self-conscious presence of the filmmaker (felt in its ‘rough’ technique) is a reminder to viewers that what they are consuming is a construct, and that the filmmakers are witnesses as much as chroniclers.[45]ibid. Untying the complexities of this is beyond the scope of this essay, but it’s clear from the filmmaker’s public utterances that the aesthetics of Woolloomooloo were about offering a riposte to the dominant narrative style of news and newscasting. ‘[Commercial news] dramatized everything and did not discuss the issues well,’ White argued in the Cinema Papers interview. ‘The resident activists were treated as being a bit silly, as though they were acting impulsively.’[46]White, quoted in Alysen, op. cit., p. 279.

White and Fiske joined others in the SFC in adopting and developing a filmmaking practice that aimed to be transparent, participatory and democratic while using rhetoric, argument and (often emotive) conceptual narrative with clearly defined conflicts and values. It was about making as convincing an argument as possible for a specific aim and against what the filmmakers understood as toxic streams in the orthodoxies of assembling and disseminating information. Woolloomooloo, for instance, contests claims based on deeply ingrained social and cultural biases (about ‘the poor’, women, protest and activists).

Rocking the Foundations is, in Fiske’s words, a ‘hybrid’. A mix of techniques form the narrative; animation and cartoons commingle with a dynamic editing style and sound design that implies and suggests as much as it explains.

Rocking the Foundations is a slicker, tighter, more supple film than Woolloomooloo, but it shares the ideology of the earlier film. Some techniques are consistent: the 1985 film was made in black-and-white, has a female narrator (in this case, Fiske herself), and employs a prodigious use of archival footage and interviews, stills and historical ephemera. Still, stylistically, Rocking the Foundations is, in Fiske’s words, a ‘hybrid’. A mix of techniques form the narrative; animation and cartoons commingle with a dynamic editing style and sound design that implies and suggests as much as it explains. Quick to remind interviewers that she is not at all ‘theoretical’, Fiske says that her personal approach to filmmaking practice is totally intuitive.

Development and technique

Who built Thebes of the seven gates?

In the books you will find the name of kings.

Did the kings haul up the lumps of rock?

– Bertolt Brecht[47]This excerpt from Brecht’s 1935 poem ‘Questions from a Worker Who Reads’ is seen at the beginning of Rocking the Foundations.

Beginning her so-called ‘formal entry’ into the film industry as a sound recordist in the late 1970s, Fiske finally returned to her NSWBLF film around 1979.[48]Fiske made several films between 1974 and 1979; these include co-directing (among other roles) the shorts Hearts & Spades (with Gillian Leahy & Virginia Coutts, 1975), Push On (with Lee Chittick, 1976) and Ladies Rooms (with Sarah Gibson & Susan Lambert, 1977). Her sound credits include Waterloo (Tom Zubrycki, 1981), while she worked as a boom operator on Wrong Side of the Road (Ned Lander, 1981) and Starstruck (Gillian Armstrong, 1982). ‘After we’d finished Woolloomooloo Denise and I parted company,’ Fiske told Metro in 2001. ‘I was a lot closer to the [NSW]BLF guys, and Woolloomooloo was what she had wanted to make anyway, so we decided I would make the film on the [NSW]BLF on my own.’[49]Pat Fiske, quoted in Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 68.

For the film’s cinematography, Fiske turned to Ansara. Born in the USA in 1942, Ansara was a cinephile involved with the peace movement (and other progressive causes). When she came to Australia in 1969, Ansara met filmmaker Jeni Thornley at the inaugural meeting of the Sydney Women’s Liberation group. Not long after, they began working on Film for Discussion (Ansara, 1973), ‘the first feminist film to commence production in Australia’.[50]Barbara Alysen, ‘Women in Australian Film, Part 4, Jeni Thornley and Martha Ansara’, Cinema Papers, no. 23, September/October 1979, p. 497. In 1974, Ansara was a convenor of the Women’s Film Workshop. Critical of a production culture that ‘exhausted’ filmmakers and bred ‘cynicism’ and ‘alienation’, Ansara – like Fiske – felt a major priority going into any production was to aim to ‘speak from inside a situation’.[51]Martha Ansara, quoted in Alysen, ibid. (At times when Ansara was unavailable, cinematographer Fabio Cavadini captured some important material.[52]Like so many activist filmmakers in the Sydney cohort, Cavadini had no formal technical training. Migrating to Australia from Milan in 1969, he became involved in the Indigenous rights movement in the early 1970s. By the time of Rocking the Foundations, he had co-directed Buried Alive: The Story of East Timor (Cavadini, Gil Scrine & Rob Hibberd, 1982).)

Working from an outline but no formal screenplay, Fiske wanted to build the narrative of Rocking the Foundations around interviews and avoid voiceover altogether. She knew most of the participants personally and, since they were articulate, shooting went smoothly. The ‘cast’ was drawn from not only NSWBLF rank and file, but also residents, executives and supporters. Theeman was not re-interviewed for Foundations (he does appear in footage taken from Woolloomooloo), but Ray Rocher of the Master Builders Association was asked to participate; he is seen in the film calmly asserting his opposition to the green bans. In a revealing letter to Rocher, Fiske deconstructed the kind of editorial technique that would have made him ‘look stupid’. She relates having told him, ‘I didn’t intercut you with anyone […] I’ve used you at the end of sections, so that you have the final say.’[53]Pat Fiske, quoted in Gillian Leahy, ‘Rocking the Foundations Interview’, Filmnews, 1 November 1985, p. 12.

Filming on building sites was not a problem, Fiske says: ‘As far as [Gallagher’s new leadership] were concerned, we were totally under the radar.’ Ansara says that shooting in high-rise situations could be hazardous: ‘We shot at Centrepoint Tower (while under construction). I knew if I stepped back to reframe, I would be over the edge.’ She adds that many camerapeople have died in similar situations.

The interviews would be ‘stylised’ where possible, carefully presented in terms of framing and location. Originally, the plan was to shoot the participants on building tops, but this proved too difficult. In the completed film, locations include the interior of a pub, high-rise sites shot from ground level, various Sydney Harbour views and homes with window views. The ultimate effect is to emphasise the shifting nature of the urban environment with a skyline made up of peaks and sudden troughs, like the graph of a flowchart. In the cut, the interviews are short grabs; most only get a few lines before the next edit. The text derived from these sources is a mix of hard info, opinion, emotional responses and, in some moments, the odd anecdote; at one point, the film breaks away altogether from filmed content to introduce an animated set piece that illustrates one of the stories being recounted.

Much of the first part of the film outlines the NSWBLF’s struggle to attain better conditions. In the cartoon sequence, a builder’s labourer tells a yarn about the time a group of workers tipped a shed into a foundation during a rainstorm. This was a form of protest: sheds were supposed to provide shelter from the elements, but in this era they were inadequate in size and poorly constructed. For the rank and file, this was a symbol of employer disdain. Two hundred builder’s labourers from fourteen city sites stopped work and descended on the trouble spot to settle the matter.

In order to create the cartoon, Fiske provided animator Paul Rolfe with photos and court drawings. Out of these references, he came up with a style that’s vivid, dignified but, in essence, realist. The sequence offers light relief, and repositions a concept of ‘protest’. In contrast, much of the vérité imagery used in the film in this context is violent; crowds battling police in the streets is a leitmotif.

At times, Rocking the Foundations seems to directly mock the aesthetics of 1950s / early 1960s Cold War films. The intricacies of Australia’s internationalist building boom of the 1960s are explained using an animated graphic: a globe sits in the frame, with Australia’s outline prominent; as the sequence progresses, great arrow-tipped lines carve parabolas from their starting points in London, Singapore and New York to ‘land’ on their destination, Sydney, doing so with a great ‘boom’ on the soundtrack. A third major animation sequence is used to demonstrate how plans (never quite carried out) would alter The Rocks and Circular Quay; here, skyscrapers surge skyward.[54]A state government–commissioned film, City of Millions (William M Carty, 1964), called these plans ‘a rebirth for one of Sydney’s oldest areas’. ‘The Rocks has long been a backwater,’ intones the narrator, over shots of sandstone buildings dating from early white settlement. ‘Picturesque here and there, but outmoded. All this is to be swept away and replaced by a well-conceived group of office buildings, modern apartments and skyscraper hotels.’ See ‘City of Millions’, YouTube, 4 June 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vj-lUejDqOY>, accessed 10 March 2022. When audiences first saw these images, there were audible gasps and incredulous laughter.[55]See Margaret Jones, ‘Vigilance the Price of Harmony’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 November 1985.

After much consultation, Fiske and Ansara elected to shoot the film on 16mm black-and-white reversal stock – a choice based both on cost and the fact that, from the start, black-and-white archival footage would make up a huge percentage of screen time. The material shot on worksites is seamlessly integrated with more contemporary footage (often drawn from the audiovisual libraries of big corporations like Civil & Civic). Rocking the Foundations is not often thought of as ‘spectacle’, but some of this building ‘action’ produces a visceral response that conveys in seconds both the danger workers faced daily and the skills they needed to complete the job. At one point, we are high above the city, where a crane holds an enormous slab of concrete; standing at each end are two workers who guide it into place, their only platform a slim piece of scaffold.

Accessing archival material – stills and moving image alike – proved laborious, and extended the length of production; Fiske says that it was a matter of ‘beg, borrow and steal’. Production was a stop-start affair: technical issues such as faulty equipment caused disruption, and interviews had to be redone. Fiske earned money as a swimming teacher and as a sound recordist between bouts of shooting, researching and editing. (Complicating things further was family illness; Fiske needed to make three unplanned trips to the USA over the course of production to see her folks.)

Financial relief came to Fiske from unexpected quarters. The green bans intersected with many subcultures sympathetic to both the humanity at the movement’s heart and the wider issues involved. One such collective was the Sydney Push, two of whose number, Margaret Fink and Darcy Waters, were acquaintances of Fiske. Known for their philosophical anarchist sympathies, members of the group saw development as threatening a way of life as well as a community many of them were deeply involved in (some even lived in the neighbourhood marked for the wrecking ball). They were also notorious punters; after a big win at the races, Fiske’s Push associates would call and offer aid. ‘A lot of lab bills were paid that way,’ she says.

Accessing archival material – stills and moving image alike – proved laborious, and extended the length of production; Fiske says that it was a matter of ‘beg, borrow and steal’.

A specific aim for Fiske was to try and make plain how and why a once-corrupt union had transitioned into a democratic, socially conscious one. The technique of relying only on interviews, it was found, was not enough to convey the confluence of factors the filmmakers felt were crucial to understanding the complexities. Writer Graham Pitts, a founder of the Sidetrack Theatre, helped Fiske draft a voiceover which she reluctantly performed.[56]Fiske tried actors, but it didn’t work; she was concerned that her American accent would be an unnecessary distraction in a story that seemed culturally specific to the Australian experience. Documentary filmmakers Bob Connolly and Robin Anderson were among many filmmakers who viewed cuts and offered advice to Fiske, especially as to how best to set up the film’s narrative.

The film opens with a truly spectacular wide-angle time-lapse – shot by Kent Whitmore – of Sydney Harbour from dusk to dawn that takes in the famous arched bridge and much of the CBD dominated by skyscrapers. After the excerpt from Brecht’s poem appears on screen, Fiske narrates:

Some people seem to have this irresistible urge to tear down and rebuild. There’s a lot of money to be made […] The developers make a fortune; the labourers make a living […] Like thousands of others, I got involved with this union; in one way or another, we got swept up in what became a powerful social movement, when the builder’s labourers put the environment – and people – ahead of their own jobs.

The images accompanying this are cut into a fast-paced rhythmic montage: sparks fly under the bite of a saw; concrete oozes like lava; long strands of ridged steel are shouldered by sweaty workers; a man rides a load of lumber into the sky as a crane lifts into place.

What gives this opening a charge is Davood Tabrizi’s score. Originally from Iran, the classically trained Tabrizi earned a reputation locally for producing innovative scores. For Rocking the Foundations, he created something simple and melodic in 6/8 (an unusual time signature in Western music) using a Roland Jupiter-8 synthesiser; its elegant figure – and epic sound, a kind of merging of church organ with a flute-like key motif – suggests triumph without bombast, loss but not defeat.

The ABC affair

On Sunday 27 March 1988, Rocking the Foundations made its national TV debut on the ABC. For Fiske, it was an anticlimax. Buried in a mid-afternoon time slot, the screening was given no publicity; adding insult to injury, it was a late program announcement, so there was no mention in weekly and weekend TV guides. It did appear, mistitled, in The Sun-Herald’s TV list on the day, which happened to be Palm Sunday – a date that, in the Cold War 1980s, was claimed for an annual national peace rally: ‘Most of our audience wouldn’t have been home,’ Fiske recalls.

Zubrycki heard rumours that ABC management felt the film was ‘too Sydney’, and that a prime-time slot was therefore not warranted.[57]Tom Zubrycki, in ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske’, op. cit. Two weeks after the screening, former ALP senator Jim McClelland saw something a little more sinister in the affair. In an op-ed for The Sydney Morning Herald that broadly addressed issues of management, costings and programming sourcing at the ABC, he wrote, ‘It is distressing to contemplate the possibility that, being an important film in terms of the Left in this country, [Rocking the Foundations] was adjudged by the moguls of the ABC to be “controversial”’.[58]James McClelland, ‘A Few Changes Could Help Aunty’s Pursuit of Excellence’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 1988.

Fiske had sent a tape of the film to McClelland. This was part of a ‘campaign’ to pressure the ABC to repurchase the film for another screening in a more sympathetic slot; ABC managers were inundated with letters and calls. In a matter of months, the ABC repurchased the film (Fiske remembers a figure of A$10,000 for both sales). The second screening went to air at 9:30pm on 29 January 1989, and was heavily promoted with a trailer (produced in house, as was the custom).

‘Just call it cinema’

In 2014, Fiske had the chance to revisit Rocking the Foundations. The film appeared at the Antenna Documentary Film Festival, and the event was presented as a tribute to both film and filmmaker. In an article published in Inside Story soon after, entitled ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, critic Sylvia Lawson reflected on the legacy of the film. ‘Seen again on the big screen in the week of Gough Whitlam’s death,’ she writes, ‘its impact connects with his due in the headlines: their story, his story, have to do with the largest issues of justice.’[59]Lawson, ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, op. cit.

By the time Rocking the Foundations finally emerged from its long gestation, it joined several other locally made documentaries about the intersection between labour relations and the sociopolitical. These include Waterloo (Zubrycki, 1981), Kemira: Diary of a Strike (Zubrycki, 1984) and For Love or Money (Megan McMurchy, Margot Nash, Margot Oliver & Thornley, 1983). But Lawson is reluctant to ghettoise Rocking the Foundations as a documentary; instead, she contextualises Fiske’s film as ‘cinema’, as part of the Australian film revival – indeed, seeing it as a rejoinder to, and of greater value than, that ‘whole stack of those genteel, conformist costume dramas that made up the prestigious art-film list’.[60]ibid. Yet Rocking the Foundations is not a film that has generated large volumes of discussion as cinema at all. Instead, on the rare occasions that it has been written about in the last thirty-five years, the nuances of protest and environmentalism, politics and feminism, dominate.

Rocking the Foundations is not a film that has generated large volumes of discussion as cinema at all. Instead, on the rare occasions that it has been written about in the last thirty-five years, the nuances of protest and environmentalism, politics and feminism, dominate.

So I would like to give Fiske and her company of collaborators the last word and the last image. Rocking the Foundations finishes with a moment that is typical of the ironic play that Fiske deploys throughout the picture, and that is of a dynamic cinematic energy worthy of Mad Max (George Miller, 1979). It is a wide-angle moving shot of a near-empty freeway. There is no visible camera platform; we seem to be hovering at very high speed above the roadway. This was achieved by strapping Cavadini, camera at shoulder, to the front of a kombi van; for balance, he stood on the vehicle’s bull bar.

The freeway in question had been diverted by the green bans.

Author acknowledgement: with thanks to Pat Fiske, Martha Ansara, Fabio Cavadini, Mandy King, David Heslin, Tait Brady, Davood Tabrizi, Debbie Sander and The State Library of New South Wales.

Select bibliography

‘A Salute to Pat Fiske: OzDox Nov 2019’, YouTube, 11 February 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1WiwF1DEEs>.

‘Documentaries: BLF History Goes Down on Film’, Encore, 21 November – 4 December 1985, p. 37.

Barbara Alysen, ‘Filming the Green Bans: 1. Woolloomooloo 2. Green City’, Cinema Papers, March/April 1979, pp. 276–9.

Annette Blonski, Barbara Creed & Freda Freiberg (eds), Don’t Shoot Darling! Women’s Independent Filmmaking in Australia, Greenhouse Publications, Richmond, Vic., 1987, pp. 193–4.

Meredith Burgmann & Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: The Saving of a City, revised edn, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2017 [1998].

Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines, Bernt Porridge, Shenton Park, WA, 2001, pp. 89–100 .

John Hughes, ‘A Work in Progress: The Rise and Fall of Australian Filmmakers Co-operatives, 1966–86’, Senses of Cinema, no. 77, December 2015, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/australian-film-history/australian-filmmakers-co-operatives/>.

Tina Kaufman & Gillian Leahy, ‘Interview with Pat Fiske’, Metro, no. 127/128, 2001, pp. 64–75.

Susan Lambert, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/rocking-the-foundations/notes/>.

Sylvia Lawson, ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, Inside Story, 30 October 2014, <https://insidestory.org.au/documentary-just-call-it-cinema/>.

Gillian Leahy, ‘Rocking the Foundations Interview’, Filmnews, 1 November 1985, pp. 12–3.

Kathy Sport, ‘Save Our Homes: Activist Documentaries 1970–1985’, Metro, no. 136, 2003, pp. 138–46,

David Stratton, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Variety, 23 October 1985.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of Release 1985 Length 87 minutes Production Company Bower Bird Films Producer Pat Fiske Director Pat Fiske Cinematographer Martha Ansara, Fabio Cavadini Editing Stewart Young, Jim Stevens, Pat Fiske Narration Pat Fiske (written by Graham Pitts & Pat Fiske) Music Davood Tabrizi Sound Lawrie Fitzgerald Sound Editor Paul Healy Associate Director Jim Stevens

Endnotes

| 1 | Thomas Waugh, ‘Why Documentary Filmmakers Keep Trying to Change the World, or Why People Changing the World Keep Making Documentaries’, in Waugh, The Right to Play Oneself: Looking Back on Documentary Film, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis & London, 2011, p. 6. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Kathy Sport, ‘Save Our Homes: Activist Documentaries 1970–1985’, Metro, no. 136, 2003, p. 142. |

| 3 | For a comprehensive overview of Fiske’s career, see Tina Kaufman & Gillian Leahy, ‘Interview with Pat Fiske’, Metro, no. 127/128, 2001, pp. 64–75; and ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske: OzDox Nov 2019’, YouTube, 11 February 2020, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n1WiwF1DEEs>, accessed 10 March 2022. |

| 4 | Author interview with Andrew Pike, 30 December 2021. |

| 5 | See Susan Lambert, ‘Curator’s Notes’, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/titles/documentaries/rocking-the-foundations/notes/>; and Sylvia Lawson, ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, Inside Story, 30 October 2014, <https://insidestory.org.au/documentary-just-call-it-cinema/>, both accessed 10 March 2022. |

| 6 | Official estimates published in 1985 put the final budget at A$150,000; Fiske today believes that its true cost is difficult to nail down. Encore reported the funding breakdown as A$119,000 from the Australian Film Commission (AFC), A$20,000 from the AFC’s Project Branch, A$5000 from Sydney City Council and A$4000 from the Music Board (Art and Working Life Project). See ‘Documentaries: BLF History Goes Down on Film’, Encore, 21 November – 4 December 1985, p. 37. |

| 7 | For a detailed discussion of the various ‘modes of documentary’ at work in Rocking the Foundations, see Sport, op. cit., pp. 138–46. |

| 8 | Matt White, ‘Pat’s Labour of Love for BLF Rocks City’s Soul’, Daily Mirror, 19 November 1985. |

| 9 | ‘Passionate Tribute’, The Daily Telegraph, 22 November 1985. |

| 10 | John Hanrahan, ‘Rocking the Foundations!’, The Sun, 21 November 1985. |

| 11 | Susie Eisenhuth, ‘Heroes of the BLF – of Yesteryear, That Is’, The Sun-Herald, 17 November 1985. |

| 12 | ‘Greenies Versus Gallagher’, The Catholic Weekly, 11 December 1985. |

| 13 | As per author interviews with Martha Ansara, Fabio Cavadini and Pat Fiske in December 2021. All unattributed quotes in this essay are sourced from these interviews. |

| 14 | Although this might seem to be an error, the divergent spelling and punctuation of the NSWBLF’s name in this subtitle is reflective of the union’s inconsistent rendering of it over the years in its own materials. See Meredith Burgmann & Verity Burgmann, Green Bans, Red Union: The Saving of a City, revised edn, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2017 [1998], p. xxi. |

| 15 | Meredith Burgmann, ‘Valé Jack Mundey: The Builders Labourers’ Leader Who Saved Glebe’, The Glebe Society website, 6 June 2020, <https://glebesociety.org.au/vale-jack-mundey-the-builders-labourers-leader-who-saved-glebe/>, accessed 9 March 2022. For a comprehensive account of the period covered in Rocking the Foundations, see Burgmann & Burgmann, ibid. It’s worth noting that Meredith Burgmann and Fiske exchanged research in order to assist each other’s project. |

| 16 | For instance, there was tremendous anxiety over the build-up of nuclear weapons; some of this protest is detailed in Midnight Oil: 1984 (Ray Argall, 2018); see Cavan Gallagher, ‘Power and the Personality: Ray Argall’s Midnight Oil: 1984’, Metro, no. 198, 2018, pp. 86–9. |

| 17 | See Paul Robinson & Brendan Donohoe, ‘A Union Becomes an Industrial Outcast’, The Age, 27 November 1985, p. 1. |

| 18 | Eisenhuth, op. cit. |

| 19 | David McKnight, ‘Rocking the Foundations – How the NSWBLF Changed Unionism’, Tribune, 20 November 1985. |

| 20 | Robyn Marshall, Rocking the Foundations review, Direct Action, November 1985. |

| 21 | Fiske credits Helen Zilko at the AFI for much of the marketing push on Rocking the Foundations. |

| 22 | David Bradbury’s Chile: Hasta Cuando? (1986) played to an audience of 6500 in its Melbourne season, he claimed; see Craig McGregor, ‘Is the Documentary Dying? Long Live Radicalism’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 May 1986. |

| 23 | Pat Fiske, quoted in Debbie Coffey, ‘The City’s Threatened Again …’, The Sun-Herald, 1 December 1985. |

| 24 | ibid. |

| 25 | See Burgmann & Burgmann, op. cit., p. xiii. |

| 26 | See ‘Newscuttings Regarding Film Rocking the Foundations’, in manuscript collection of Australian Building Construction Employees’ and Builder’s Labourers’ Federation New South Wales Branch, MLMSS 4879 / Box MLK4272 / Item [19], State Library of New South Wales. Fiske is mystified as to how this material ended up in this collection! |

| 27 | See Anthony Buckley, Behind a Velvet Light Trap: A Filmmaker’s Journey from Cinesound to Cannes, Hardie Grant Books, Melbourne, 2009, pp. 223–34; and Ingo Petzke, Phillip Noyce: Backroads to Hollywood, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 2004, p. 108. Nielsen has long been the subject of books, TV documentaries and radio specials – most recently, a two-part TV series directed by Kriv Stenders, Juanita: A Family Mystery (2021), which was released alongside an accompanying ABC podcast. |

| 28 | David Stratton, ‘Rocking the Foundations’, Variety, 23 October 1985. |

| 29 | Norm Gallagher, quoted in Burgmann & Burgmann, op. cit., p. 54. |

| 30 | Burgmann & Burgmann, ibid., pp. 273–4. |

| 31 | See, for example, Tony Mitchell, ‘Rock Solid: Rocking the Foundations’, Cinema Papers, no. 55, January 1986, p. 63. |

| 32 | John Hughes, ‘A Work in Progress: The Rise and Fall of Australian Filmmakers Co-operatives, 1966–86’, Senses of Cinema, no. 77, December 2015, <https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2015/australian-film-history/australian-filmmakers-co-operatives/>, accessed 10 March 2022. |

| 33 | Tom Zubrycki, in ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske’, op. cit. |

| 34 | Hughes, op. cit. |

| 35 | Barrett Hodsdon, Straight Roads and Crossed Lines, Bernt Porridge, Shenton Park, WA, 2001, p. 91. For an excellent account of the SFC, see pp. 89–100 of this book. |

| 36 | Filmmakers received 50 per cent of rentals and 75 per cent of print sales; see Sylvia Lawson, ‘Does the Film Co-op Deserve to be Saved?’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 21 January 1986. The wording I use here is paraphrased from filmmaker Margot Nash, quoted in Hughes, op. cit. |

| 37 | According to Fiske, Matt Butler, who delivered the workshop, called it ‘Blinky Bill’ because he found the character non-threatening, unmistakably Australian (‘dinky-di’, he says) and, happily, out of copyright. |

| 38 | Denise White, quoted in Barbara Alysen, ‘Filming the Green Bans: 1. Woolloomooloo 2. Green City’, Cinema Papers, March/April 1979, p. 276. |

| 39 | Pat Fiske, quoted in Alysen, ibid., p. 276. |

| 40 | Fiske says that estimates are unreliable. For instance, the figure of A$13,000 has been quoted elsewhere. See Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 67. |

| 41 | See, for example, Alysen, op. cit. |

| 42 | White, quoted in Alysen, ibid., p. 279. Emphasis added. |

| 43 | Fiske, quoted in Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 67. |

| 44 | Sport, op. cit., p. 144. |

| 45 | ibid. |

| 46 | White, quoted in Alysen, op. cit., p. 279. |

| 47 | This excerpt from Brecht’s 1935 poem ‘Questions from a Worker Who Reads’ is seen at the beginning of Rocking the Foundations. |

| 48 | Fiske made several films between 1974 and 1979; these include co-directing (among other roles) the shorts Hearts & Spades (with Gillian Leahy & Virginia Coutts, 1975), Push On (with Lee Chittick, 1976) and Ladies Rooms (with Sarah Gibson & Susan Lambert, 1977). Her sound credits include Waterloo (Tom Zubrycki, 1981), while she worked as a boom operator on Wrong Side of the Road (Ned Lander, 1981) and Starstruck (Gillian Armstrong, 1982). |

| 49 | Pat Fiske, quoted in Kaufman & Leahy, op. cit., p. 68. |

| 50 | Barbara Alysen, ‘Women in Australian Film, Part 4, Jeni Thornley and Martha Ansara’, Cinema Papers, no. 23, September/October 1979, p. 497. |

| 51 | Martha Ansara, quoted in Alysen, ibid. |

| 52 | Like so many activist filmmakers in the Sydney cohort, Cavadini had no formal technical training. Migrating to Australia from Milan in 1969, he became involved in the Indigenous rights movement in the early 1970s. By the time of Rocking the Foundations, he had co-directed Buried Alive: The Story of East Timor (Cavadini, Gil Scrine & Rob Hibberd, 1982). |

| 53 | Pat Fiske, quoted in Gillian Leahy, ‘Rocking the Foundations Interview’, Filmnews, 1 November 1985, p. 12. |

| 54 | A state government–commissioned film, City of Millions (William M Carty, 1964), called these plans ‘a rebirth for one of Sydney’s oldest areas’. ‘The Rocks has long been a backwater,’ intones the narrator, over shots of sandstone buildings dating from early white settlement. ‘Picturesque here and there, but outmoded. All this is to be swept away and replaced by a well-conceived group of office buildings, modern apartments and skyscraper hotels.’ See ‘City of Millions’, YouTube, 4 June 2018, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vj-lUejDqOY>, accessed 10 March 2022. |

| 55 | See Margaret Jones, ‘Vigilance the Price of Harmony’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 November 1985. |

| 56 | Fiske tried actors, but it didn’t work; she was concerned that her American accent would be an unnecessary distraction in a story that seemed culturally specific to the Australian experience. |

| 57 | Tom Zubrycki, in ‘A Salute to Pat Fiske’, op. cit. |

| 58 | James McClelland, ‘A Few Changes Could Help Aunty’s Pursuit of Excellence’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 April 1988. |

| 59 | Lawson, ‘Documentary? Just Call It Cinema’, op. cit. |

| 60 | ibid. |