On 15 September 2017, director Mohammad Rasoulof was returning to Tehran from the Telluride Film Festival, where his film A Man of Integrity (2017) – which premiered at Cannes that May – had screened. At the airport, his passport was confiscated, meaning he was effectively unable to leave the country.[1]Nancy Tartaglione, ‘Iran Pulls Filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof’s Passport as Award Winner Returns Home’, Deadline Hollywood, 18 September 2017, <http://deadline.com/2017/09/iran-mohammad-rasoulof-passport-confiscated-film-director-1202172323/>, accessed 28 February 2018. On 3 October, he was then ‘interviewed extensively’ by Iranian intelligence, with charges looming for crimes against the state.[2]‘Award-winning Iranian Film-maker Faces Six-year Jail Term’, Al Arabiya, 11 October 2017, <http://english.alarabiya.net/en/media/television-and-radio/2017/10/11/Award-winning-Iranian-film-maker-faces-six-year-jail-term-.html>, accessed 28 February 2018.

Rasoulof is no stranger to run-ins with Iranian authorities. In 2010, in an event that drew international attention and screen-industry condemnation, he and fellow filmmaker Jafar Panahi were arrested and charged with ‘assembly and colluding with the intention to commit crimes against the country’s national security and propaganda against the Islamic Republic’, for having dared to make a film in support of the opposition Green Movement. Rasoulof was sentenced to six years imprisonment and a twenty-year ban from leaving Iran, before the ruling on the former was appealed and reduced to a year.[3]Kaleem Aftab, ‘Banned Iranian Director Mohammad Rasoulof to Attend Cannes Film Festival 2013, His First Public Appearance Since Prison’, The Independent, 23 May 2013, <http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/banned-iranian-director-mohammad-rasoulof-to-attend-cannes-film-festival-2013-his-first-public-8629416.html>, accessed 28 February 2018. The director was also officially forbidden from making films – but, defiantly (‘When the judge in charge of my case sentenced me […] I laughed at him and said, “You are jeopardising national security by condemning artists,”’ recounts Rasoulof[4]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Nigel Andrews, ‘Reel Revolution’, Financial Times, 22 June 2013, <https://www.ft.com/content/3530dcb8-d98d-11e2-bab1-00144feab7de>, accessed 28 February 2018. ), he kept working.

Rasoulof’s early films are elaborate parables or indirect critiques of the state: Iron Island (2005) turns the rusted hulk of a beached ship into a symbolic, totalitarian micro-society; Head Wind (2008) is a documentary chronicle of Iran’s black market of illegal satellite-dish installations; and The White Meadows (2009) is a pure allegory in which a boatman collects the tears of people living on islands made of salt. But, having been persecuted – and accused of propaganda! – anyway, the filmmaker suddenly felt emboldened, and pledged to be more direct in his stories: ‘I had spent all these years developing this metaphorical language to stay out of trouble. But when I came out of prison I realized I didn’t have anything to lose.’[5]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Sune Engel Rasmussen, ‘An Iranian Dissident Returns Home’, Al Jazeera, 3 July 2014, <http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/7/3/an-iranian-dissidentreturnshome.html>, accessed 28 February 2018.

So, in Goodbye (2011), we see an attorney whose licence to practise is revoked, leading to a dispiriting battle with bureaucracy. Though the movie, made covertly when Rasoulof was forbidden from filmmaking, was an act of rebellion, its acceptance into Cannes led Iranian authorities to lift the ban on him leaving the country. Rasoulof proceeded to go to France, where he accepted the award for Best Director in the Un Certain Regard strain, support for an outlawed filmmaker forever a cinematic cause célèbre. Rather than seek exile from Iran upon exiting it, Rasoulof chose to return, preferring to make his filmic critiques at home, agitating for change from the inside. His next movie, Manuscripts Don’t Burn (2013), was his most direct rebuke of the country. Shot covertly, with its cast and crew remaining unnamed in the credits, it shows intellectuals and artists under surveillance, harassed by censors and, ultimately, being executed, inspired by real-life killings that occurred in the late 1990s.[6]Stefan Buchen, ‘Iranian Agents as Killers’, Qantara.de, 24 May 2013, <https://en.qantara.de/content/mohammed-rasoulofs-manuscripts-dont-burn-iranian-agents-as-killers>, accessed 28 February 2018. Its title refers to Mikhail Bulgakov’s 1967 novel The Master and Margarita, a satirical parable written at the height of Stalinist repression; and there’s shades of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, too, in Rasoulof’s depiction of men caught in the mechanisms of a totalitarian regime.

After being allowed to travel to Cannes for the premiere of Manuscripts Don’t Burn, Rasoulof’s passport was confiscated in late 2013 – when he was due to leave Iran to appear at the Nuremberg International Human Rights Film Festival, no less.[7]Melanie Goodfellow, ‘Iran Blocks Rasoulof Travel’, Screen Daily, 2 October 2013, <https://www.screendaily.com/festivals/other-festivals/iran-blocks-rasoulof-travel/5061046.article>, accessed 28 February 2018. By that stage, his entire career had played out outside of the Iranian state: made without permits and never officially screened in Iran, his films found a life solely at foreign festivals. With A Man of Integrity, Rasoulof attempted to avoid trouble by working with authorities: this time, he shot with a permit, his initial script needing to be approved by the local censors. The film was unlikely to ever screen in Iran, but it wasn’t an act of covert dissidence, either. Nevertheless, production itself was still a clandestine endeavour, with filming done in secret for fear of reprisal or retribution. A Man of Integrity premiered at Cannes, where it won the Prix Un Certain Regard; on the Riviera, Rasoulof acknowledged that the festival’s support of Iranian auteurs had ‘really helped all filmmakers and especially me, by stopping the pressure [Iranian authorities] were putting on us’.[8]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Robin Pomeroy, ‘Iranian Film A Man of Integrity Wins “Certain Regard” Competition at Cannes’, Reuters, 28 May 2017, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-filmfestival-cannes-un-certain-regard/iranian-film-a-man-of-integrity-wins-certain-regard-competition-at-cannes-idUSKBN18N0TO>, accessed 28 February 2018. If that statement seems ironic, given what would happen to Rasoulof soon thereafter, another statement he made at Cannes proved more prophetic: ‘I love Iran, but it’s like an alcoholic father, sometimes it hits me.’[9]ibid.

With due symbolism, A Man of Integrity is a drama about a man persecuted by authorities, battling against an unjust society. His refusal to play the same games as others – corruption, collusion, cronyism – is self-defeating, his virtue not rewarded but punished.

With due symbolism, A Man of Integrity is a drama about a man persecuted by authorities, battling against an unjust society. His refusal to play the same games as others – corruption, collusion, cronyism – is self-defeating, his virtue not rewarded but punished. ‘Given the choice between being a tyrant or a victim, he’s decided to choose neither,’ Rasoulof explains. ‘But so long as he insists on preserving his integrity, others treat him as though he were an idiot.’[10]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Mark Danner, ‘Telluride Film Festival, 2017: Mark Danner Interviews Mohammad Rasoulof’, Mark Danner official website, 13 August 2017, <http://www.markdanner.com/orations/telluride-film-festival-2017-mark-danner-interviews-mohammad-rasoulof>, accessed 28 February 2018.

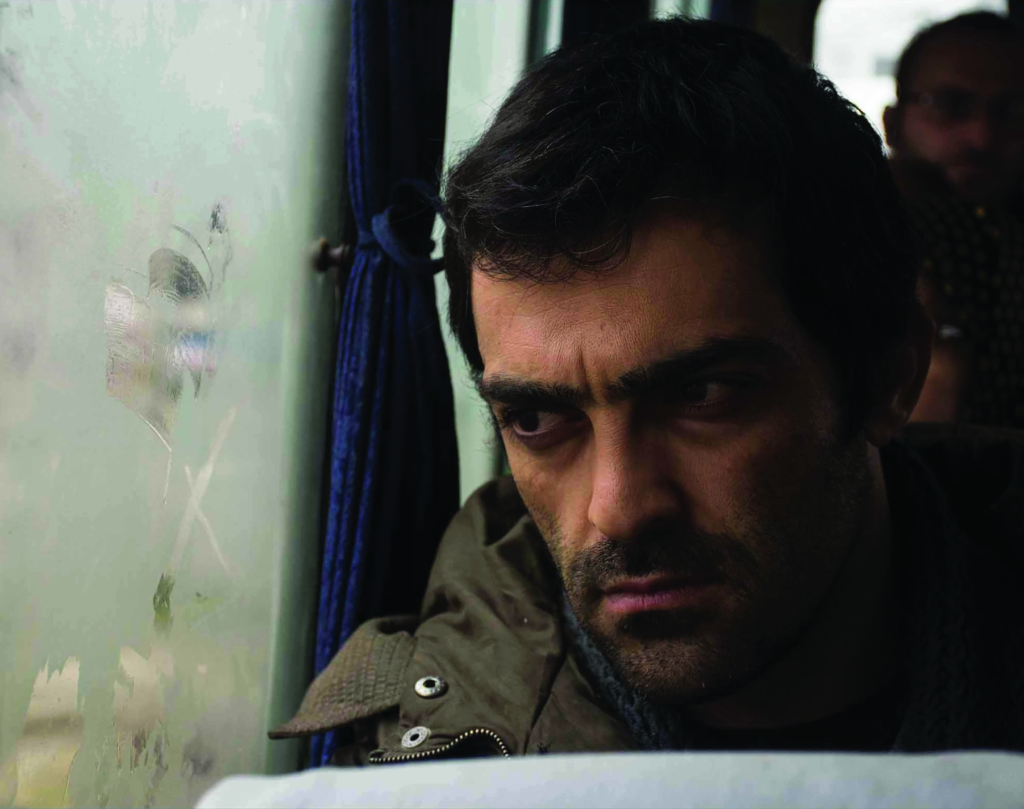

Reza (Reza Akhlaghirad) has moved from Tehran to rural Northern Iran, hoping to start a new life. In the city, both he and his wife, Hadis (Soudabeh Beizaee), were teachers, but Reza is now but a lowly goldfish farmer, tending to a dirty stretch of water in the middle of nowhere. Like the frontiersmen of yore, Reza has left civilisation behind, hoping to carve out a modest life with wife and son in a place where they’ll be left alone. But left alone they’re not. For starters, they don’t yet own this land they want to make their own. Reza is late on his bank-loan payments and, on top of that, he has to pay fines for these late payments. The bank manager offers to make the fines disappear if an under-the-table deal can be reached. Reza refuses, instantly shown as a man whose unwavering values may not be the smartest – or, at least, stand in opposition to the way things are normally done. With his loan looking shaky, a private water company seeks to buy him out. He, of course, refuses, which leads to a campaign of land-grabbing harassment: his water is shut off; his fish die; he’s arrested and held to pay exorbitant recompense for getting in a fight with the company’s area overseer, Abbas (Misagh Zare), a local made man who serves as the villainous embodiment of corruption, injustice, patriarchy, oppression.

The fact that Reza’s goldfish may’ve died in an act of sabotage – when a Hitchcockian murder of crows descends, en masse, to eat the dead fish, it’s an unexpected moment of stylised, CGI-aided spectacle in an otherwise-dour picture – is doubly destructive, because his insurance policy only covers accidental loss, not purposeful death. The water company’s offers to buy his property decrease in value: it can’t officially buy from him, it says, as this would make for bad PR, so it can only offer a side deal. And any attempts to call the company into question fail: it operates above the law, with local police, lawyers, doctors, judges and the mayor all on its payroll. Reza spends a stint in prison that a bribe could’ve helped him avoid, but ‘Reza wouldn’t pay a bribe, even if I was in jail,’ Hadis laments. She’s the one left to get him out from behind bars and find other ways – using her position as school principal to exercise blackmail, soliciting powerful company men with her womanly charms – to work around her husband’s unassailable morals, his stubborn refusal to swallow his macho pride. She’s the one who, in a telling moment, informs Reza that a friend back in Tehran has been arrested for ‘breaching national security’ and given a six-year sentence – clearly, a nod to Rasoulof’s own legal struggles.

Cornered and past the point of no return, Reza becomes a man on a mission, powered by the familiar cinematic currency of righteous vengeance. While his life continues to fall apart – after hired goons show up to threaten the family, his wife and son move out in fear of retribution; later, their house is burnt down, which Reza doesn’t bother to mention to Hadis – he commits to an elaborate act of revenge. In his sights is Abbas, whose position and connections have made him, legally, beyond Reza’s reach. So, hiding out in a shed where he ferments homemade (and very illegal) hooch from old watermelons, Reza concocts a scheme to enact his own form of justice. His best-laid plans involve inveigling himself with a prison inmate, taking possession of an opium stash and devising a set-up whose sting is a lethal sleight of hand. We learn of his plan’s success – and Abbas’ timely death – indirectly, when, at the film’s denouement, Reza shows up at his funeral. Rather than being run out of the gathering as someone who’d clashed with the deceased, our protagonist has now, having begun to play their game by its rules, earned the respect of the locals. In the end, Reza gets more than what his act of revenge was ever designed to achieve: he’s offered Abbas’ old job as the water company’s local man in charge, and backroom powers-that-be are conspiring to have him made mayor. He is, after all, a man of integrity.

A Man of Integrity is a morality play, told as if a thriller. But it also evokes the classic western: an honest, Eastwoodian man with ‘a blank and emotionless look’, wanting only to be left alone, is pushed too far by bad people and takes a ruthless stand.

Though its international English title is both noble and somewhat ironic, the original Iranian title, Lerd, suggests something else. It refers to a type of sediment, which alludes not just to the muddy tracts of water in the goldfish farm, but also to the people who tend it; a better English translation would be ‘dregs’, evoking, as it does, the lowest members of society. The title, Rasoulof says, hints at trickle-down effects, the way ‘problems started first from levels that were higher up, from the level of politics, those that are in power and gradually they came and settled within the general culture […] in the place that belongs to everyone’.[11]ibid.

The international title helps frame the film as being about a hero’s journey (‘You think you’re a hero,’ a teacher says to Reza, mockingly, as if ‘hero’ equates to egotist, fool). With the lauded quality in its name, A Man of Integrity is, in turn, a morality play, told as if a thriller. But it also evokes the classic western: an honest, Eastwoodian man with ‘a blank and emotionless look’,[12]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Tarik Khaldi, ‘Lerd, Interview with Mohammad Rasoulof’, Cannes Film Festival website, 19 May 2017, <http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/festival/actualites/articles/lerd-interview-with-mohammad-rasoulof>, accessed 28 February 2018. wanting only to be left alone, is pushed too far by bad people and takes a ruthless stand. It’s a tribute to defiance and, eventually, a film that justifies the lawless recourse of an act of deadly revenge: villains beaten in their own game by a man driven to desperation. Yet the narrative’s central moral – that even an incorruptible man can be corrupted by society – throws a pall over this heroic tale, which, as much as anything, is about the limits of one person’s agency. This is in keeping with the film’s grander themes: oppressive social structures, individuals suffering under forces beyond their control, the dehumanisation felt by many citizens of modern Iran.

‘The forces [Reza] faces, his antagonist,’ offers Rasoulof, ‘is this structure that is comprised of the forces of power, of capital, and of those who, in order to attain that power and that capital […] attach themselves to the governing body.’[13]Rasoulof, quoted in Danner, op. cit. The director isn’t just telling a human story; in A Man Of Integrity, he ‘also analyses and criticises society [… and its] centralised power structure’, says co-producer Kaveh Farnam.[14]Kaveh Farnam, quoted in ‘Kaveh Farnam on His Co-production with Mohammad Rasoulof’, BroadcastPro Middle East, 10 August 2017, <http://broadcastprome.com/interviews/kaveh-farnam-on-his-co-production-with-mohammad-rasoulof/>, accessed 28 February 2018. This means A Man of Integrity can be considered part of that particular Iranian cinematic tradition that uses a straightforward story and a social-realist milieu to level a critique of greater society. ‘In this country, you’re either the oppressed or the oppressor,’ says Hadis, this simple binary a cutting summation of the cruel climes both characters and filmmaker find themselves in. ‘The social situation [depicted in A Man of Integrity] is close to the nightmarish reality we live,’ Rasoulof says. ‘We must show how the structure in place influences the intimate life of individuals.’[15]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Yal Sadat, ‘Mohammed [sic] Rasoulof: “Le Cinéma Iranien Est une Route et Chaque Cinéaste a Sa Propre Voiture”’, Premiere, 27 May 2017, <http://www.premiere.fr/Cinema/News-Cinema/Mohammed-Rasoulof-Le-cinema-iranien-est-une-route-et-chaque-cineaste-a-sa-propre>, accessed 28 February 2018, as translated by Google Translate. Examining such power structures has long been on the filmmaker’s mind: ‘[K]ings have ruled people by subjecting them to oppression and injustice,’ offers Rasoulof. ‘I used to ask myself, how is this possible? I think that I am still asking the same questions.’[16]Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in ‘Kaveh Farnam on His Co-production’, op. cit.

Endnotes

| 1 | Nancy Tartaglione, ‘Iran Pulls Filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof’s Passport as Award Winner Returns Home’, Deadline Hollywood, 18 September 2017, <http://deadline.com/2017/09/iran-mohammad-rasoulof-passport-confiscated-film-director-1202172323/>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Award-winning Iranian Film-maker Faces Six-year Jail Term’, Al Arabiya, 11 October 2017, <http://english.alarabiya.net/en/media/television-and-radio/2017/10/11/Award-winning-Iranian-film-maker-faces-six-year-jail-term-.html>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 3 | Kaleem Aftab, ‘Banned Iranian Director Mohammad Rasoulof to Attend Cannes Film Festival 2013, His First Public Appearance Since Prison’, The Independent, 23 May 2013, <http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/banned-iranian-director-mohammad-rasoulof-to-attend-cannes-film-festival-2013-his-first-public-8629416.html>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 4 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Nigel Andrews, ‘Reel Revolution’, Financial Times, 22 June 2013, <https://www.ft.com/content/3530dcb8-d98d-11e2-bab1-00144feab7de>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 5 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Sune Engel Rasmussen, ‘An Iranian Dissident Returns Home’, Al Jazeera, 3 July 2014, <http://america.aljazeera.com/articles/2014/7/3/an-iranian-dissidentreturnshome.html>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 6 | Stefan Buchen, ‘Iranian Agents as Killers’, Qantara.de, 24 May 2013, <https://en.qantara.de/content/mohammed-rasoulofs-manuscripts-dont-burn-iranian-agents-as-killers>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 7 | Melanie Goodfellow, ‘Iran Blocks Rasoulof Travel’, Screen Daily, 2 October 2013, <https://www.screendaily.com/festivals/other-festivals/iran-blocks-rasoulof-travel/5061046.article>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 8 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Robin Pomeroy, ‘Iranian Film A Man of Integrity Wins “Certain Regard” Competition at Cannes’, Reuters, 28 May 2017, <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-filmfestival-cannes-un-certain-regard/iranian-film-a-man-of-integrity-wins-certain-regard-competition-at-cannes-idUSKBN18N0TO>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 9 | ibid. |

| 10 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Mark Danner, ‘Telluride Film Festival, 2017: Mark Danner Interviews Mohammad Rasoulof’, Mark Danner official website, 13 August 2017, <http://www.markdanner.com/orations/telluride-film-festival-2017-mark-danner-interviews-mohammad-rasoulof>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 11 | ibid. |

| 12 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Tarik Khaldi, ‘Lerd, Interview with Mohammad Rasoulof’, Cannes Film Festival website, 19 May 2017, <http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/festival/actualites/articles/lerd-interview-with-mohammad-rasoulof>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 13 | Rasoulof, quoted in Danner, op. cit. |

| 14 | Kaveh Farnam, quoted in ‘Kaveh Farnam on His Co-production with Mohammad Rasoulof’, BroadcastPro Middle East, 10 August 2017, <http://broadcastprome.com/interviews/kaveh-farnam-on-his-co-production-with-mohammad-rasoulof/>, accessed 28 February 2018. |

| 15 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in Yal Sadat, ‘Mohammed [sic] Rasoulof: “Le Cinéma Iranien Est une Route et Chaque Cinéaste a Sa Propre Voiture”’, Premiere, 27 May 2017, <http://www.premiere.fr/Cinema/News-Cinema/Mohammed-Rasoulof-Le-cinema-iranien-est-une-route-et-chaque-cineaste-a-sa-propre>, accessed 28 February 2018, as translated by Google Translate. |

| 16 | Mohammad Rasoulof, quoted in ‘Kaveh Farnam on His Co-production’, op. cit. |