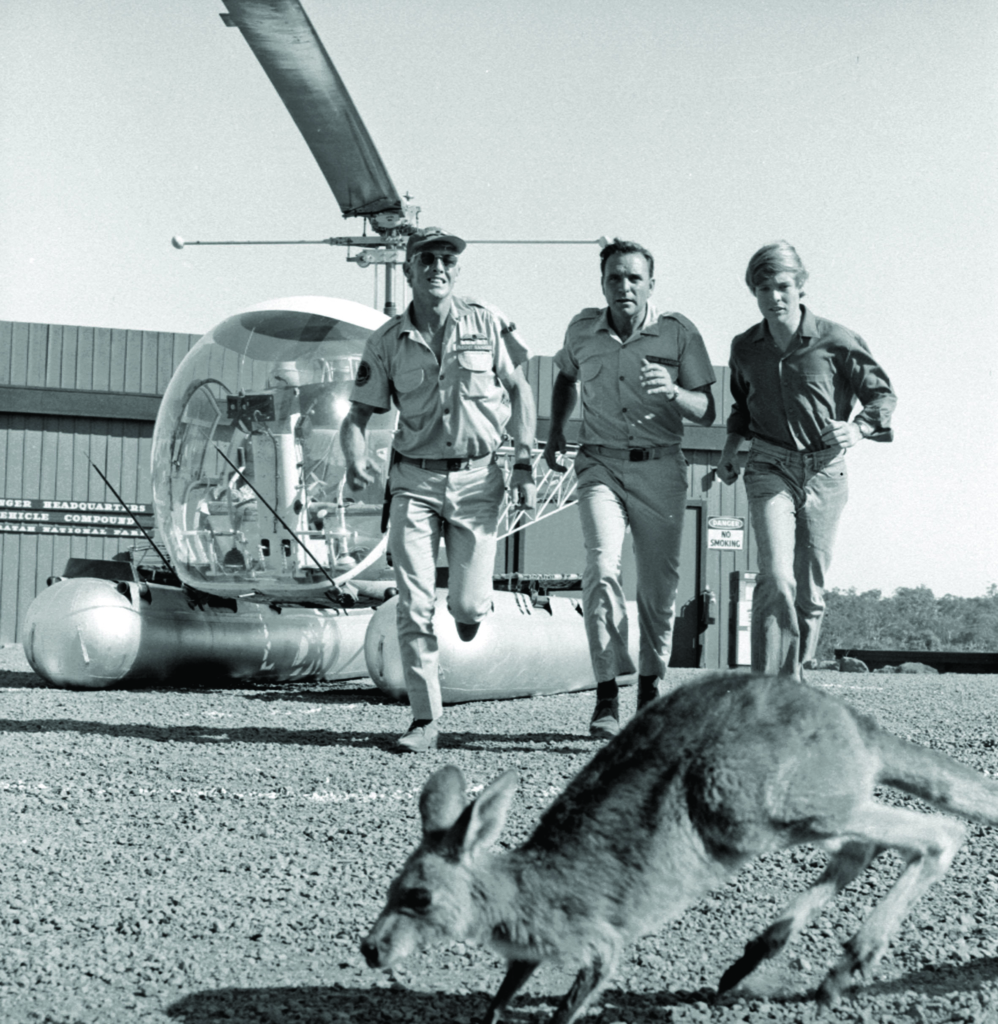

In March 1970, the final episode of Skippy the Bush Kangaroo was aired in prime time on the Nine Network in Sydney and Melbourne. This episode, ‘Fred’, has Sir Adrian (John Warwick), chairman of the National Park Trust and a world-class surgeon, buying protected wildflowers from an old lady vendor in downtown Sydney that have come from the nearby Waratah National Park. The park is run by the principled head ranger Matt Hammond (Ed Deveraux), who is bringing up two sons, young Sonny (Garry Pankhurst) and teenage Mark (Ken James), on the nature reserve. Sir Adrian learns that this theft of native flora has occurred before, with the mythical Fred being fingered as the culprit. Sir Adrian, Mark and Matt manage to foil the flower thieves’ operation, but not without the help of Skippy, a super-intelligent, crime-fighting kangaroo with extraordinary manual dexterity. ‘Fred’ is neatly wrapped up within the three-act structure of a twenty-five-minute episode, with the two thieves getting community work at the park.

By the time Skippy had had its Sydney premiere two years earlier, on 5 February 1968, shows for children (and the family) had already become a mainstay of Australian programming. Many of these series – like the Disney ratings juggernaut The Mickey Mouse Club – had been imported from the United States. From the medium’s humble beginnings in September 1956, however, Australia has had a rich and multifarious tradition of homegrown product for the younger set, including Desmond and the Channel 9-Pins (TCN-9), the long-running variety program The Tarax Show (GTV-9), The Terrific Adventures of the Terrible Ten (GTV-9), Here’s Humphrey (NWS-9) and Mr. Squiggle and Friends (ABC).[1]For detailed accounts of early children’s television in Australia, see Brian Davies, Those Fabulous TV Years, Cassell Australia, North Ryde, NSW, 1981; Brendan Horgan, Radio with Pictures! 50 Years of Australian Television, Lothian, Sydney, 2006; and Andrew McKay, ‘Kids’, in Peter Beilby (ed.), Australian TV: The First 25 Years, Nelson & Cinema Papers, Melbourne, 1981, pp. 122–33. But whereas these were local successes, Skippy’s popularity would extend well beyond its national boundaries to become a truly international phenomenon; Skippy ‘herself’ would become a star.

Produced with an eye to the international market, the series was the brainchild of actor–turned–executive producer John McCallum, pioneering Australian filmmaker Lee Robinson, Sydney lawyer Bob Austin and cameraman Dennis Hill, who all came together on the landmark British–Australian film They’re a Weird Mob (Michael Powell, 1966).[2]John McCallum, Life with Googie, Heinemann, London, 1979, pp. 232–3. Both McCallum and Austin were unhappy with their return as investors after distributors and exhibitors took their cuts on the film, and so turned to making television instead of cinema. For this purpose, they formed Fauna Productions, also known (for taxation purposes) as Norfolk International,[3]See Don Storey, ‘Skippy’, Classic Australian Television, 2013,<https://www.classicaustraliantv.com/Skippy.htm>, accessed 18 May 2020. and set about producing a quality children’s series for the world market. Robinson and Hill were the main creative forces behind the program, and it appears that Robinson came up with the basic idea for a series based on a kangaroo after seeing the 1960s American adventure series about a super-intelligent dolphin, Flipper. ‘It was certainly Lee,’ recalls McCallum in his 1979 memoir, ‘who came up with the name “Skippy”, and Lee deserves most of the credit for the series.’[4]McCallum, op. cit., p. 232. From Flipper, the producers lifted the basic family situation of a widower park-ranger father raising two boys in a fictional animal park. Later, Clancy Merrick (played by the very English Liza Goddard), the daughter of a ranger in another area of the park who comes to stay with the Hammonds, was added by the producers to bring a much-needed feminine quality to the program.

Even when we consider that the television market was much less fragmented at the time, Skippy’s global viewership of 300 million per week truly astounds.[5]Russell Clark, ‘Multi-million Dollar Marsupial’, TV Times, 6 January 1971, p. 8. It was sold to over eighty countries, including New Zealand, the UK, Canada, Japan, various European nations and even the hard-to-crack US. It was also a merchandising goldmine, spawning Skippy-branded products of everything from water bottles, soap and toothpaste to tableware and apparel. There were also Skippy books, records (including versions of Eric Jupp’s memorable theme song, one sung by Deveraux himself), a John Sands board game and a fan club. A spin-off film entitled The Intruders, written and directed by Robinson, was released in 1969 to help sell the series to America; and the same year, the show won a special Logie, Australia’s equivalent to the Emmy, for Best Export Production.

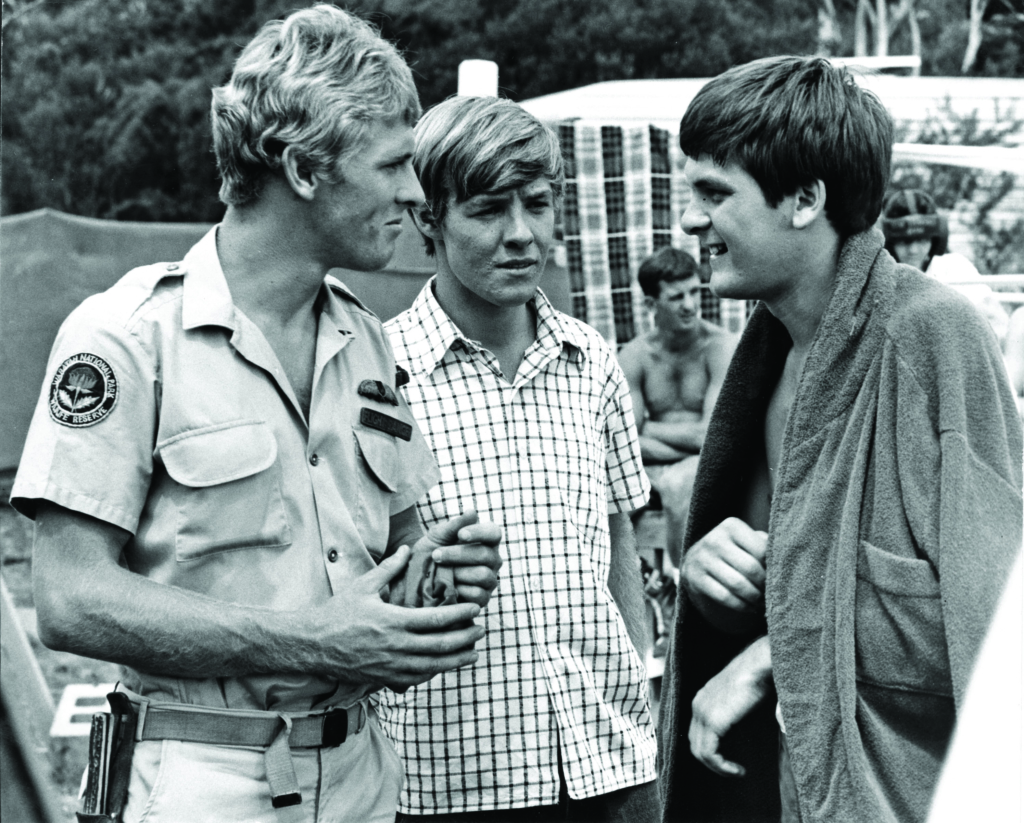

Before being cast in the role of Mark, James had appeared in the children’s drama The Adventurers, produced for ATN-7 Sydney. In 1967, James left a scholarship place at Sydney’s National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) for a recurring role in the series. He had already appeared in the pilot, which was shown to Sir Frank Packer, then head of the Nine Network; despite some mishaps in the projection room, Packer was enthusiastic about the program, and he bought it on a handshake deal.[6]See Dianne Butler, ‘Skippy Hits the Spot with Frank Packer’, The Courier Mail, 17 September 2009, <https://www.couriermail.com.au/news/skippy-hits-the-spot-with-frank-packer/news-story/153b3c22d97051cfce1fff9eebfd41a2>; and David Knox, ‘Is This Our Oldest TV Show to Still Be in Reruns?’, TV Tonight, 5 May 2016, <https://tvtonight.com.au/2016/05/is-this-our-oldest-tv-series-to-still-be-in-reruns.html>, both accessed 18 May 2020. ‘No-one in their wildest dreams could have predicted how successful the show would be,’ James tells me. Five years James’ senior, Bonner had done some television for the ABC in Sydney, as well as music hall and theatre. He made an impression as a lifesaver in They’re a Weird Mob, so much so that Hill called him to offer him the role of flight ranger Jerry King in the new series he was co-producing. The up-and-coming actor enthusiastically accepted, particularly when he learned about its no-expense-spared production values. ‘Everything then was in black-and-white or black-and-white tape,’ Bonner tells me. ‘So for a younger actor back then in 1967 to be working on a daily basis on film and colour film, that was just too good for me to pass up.’

Skippy was shot almost entirely on location, and it would be no exaggeration to say that the show’s images of native flora and fauna put Australia on the map.

The series mostly revolves around Sonny’s adventures with his marsupial companion. When line producer Robinson was developing the philosophy for the series, he stressed the freedom of both the kangaroo, who is not a pet and can come and go as she pleases, and Sonny, who is also free to roam around the bush.[7]Skippy: Australia’s First Superstar, DVD, DV1, 2009. Pankhurst had been spotted by a talent agent, leading to work in commercials; at the age of ten, he was cast as Sonny. When production wrapped up after ninety-one episodes in September 1969, Pankhurst opted out of acting and the limelight altogether. Although he was upset when the series eventually came to an end, he has said that he found the adulation as a child actor somewhat overwhelming.[8]ibid. James elaborates: ‘Garry’s career began at the age of ten and finished at thirteen or fourteen. He didn’t want to be an actor; he wanted to be a little boy.’ Today, James has unreserved praise for his former co-star: ‘The camera loved him, and he was very photogenic. He also had a photographic memory; he could look at a page of dialogue and get it down like “bang”. He was extremely natural.’

The year 1968, when Skippy was first shown on Australian television, has been seen as one of the world’s most turbulent: in the United States, it’s often seen as its annus horribilis, with the back-to-back assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert F Kennedy, anti–Vietnam War demonstrations in the streets, the Tet Offensive, and the protests at the Chicago Democratic National Convention. Even for a wholesome television series, Skippy seems curiously decontextualised, as if conceived in a parallel universe. I asked James and Bonner about this aspect of the show. ‘I think Australia was in a cultural bubble,’ says James. ‘We weren’t that sophisticated, quite frankly, when you look at the world stage.’ He adds, ‘What it was was a show about an Australian family with great values, with family values: good, genuine and honest.’ James believes there was a strong aspect of wish fulfilment to the show’s successful formula: ‘Every kid, as far as I was concerned, wanted to have a kangaroo like Skippy. All the kids wanted me, as Mark, to be their big brother.’ Bonner also makes the valid point that Skippy ‘wasn’t the platform, the voice [… for] anti–Vietnam War protesters [… or] about whatever problems Australia may have had at the time; it was a show about a family trying to do its best.’ The closest the show came to evoking Australia’s controversial involvement in the escalating Vietnam War was in the unusual episode ‘Rockslide’, about a national-service deserter.

And yet the show was at the vanguard on conservation and Indigenous issues. Long before the Australian Children’s Television Foundation was founded in 1982 to emphasise distinctively Australian, including Indigenous, perspectives in children’s programming, Skippy inspired a generation or two of youngsters to learn more about this island continent. In 1964, Australia’s first national conservation body, the Australian Conservation Foundation, was formed, and the late 1960s and 1970s witnessed a series of hard-won campaigns to protect areas in Australia from mining and related interests; the episode ‘The Empty Chair’ dramatises the clash between those competing concerns. When workmen from Archer Oil Service start test drilling for oil in Waratah National Park, this provokes grave fears for the future of the park, with Mr Hammond likening it to a death sentence. Sonny realises that the owner of the company is his friend Miles Vincent Archer (Gerry Duggan), who has been posing as the ‘hobo’ Mr Trundle, and he must persuade him to stop drilling in the park.

Skippy was shot almost entirely on location (with camera mounts on vehicles instead of rear projection), and it would be no exaggeration to say that the show’s images of native flora and fauna put Australia on the map. It was the perfect advertisement for tourism, made explicit in the episode ‘Ten Little Visitors’, in which Sonny gives a group of international children a guided tour of the park and displays his considerable knowledge of Australia’s weird and wonderful bush creatures. Bonner also believes the show assisted the government with its immigration plans:

The [number] of people in England, Ireland, Wales and Scotland [who] saw this television series [… and] immigrated to Australia when they saw this beautiful country – with beaches just near the city, bushlands, blue skies – in colour was phenomenal.

These included some of the so-called ten-pound poms who came to Australia on the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, which had been introduced by Ben Chifley’s Labor government in 1945. But it wasn’t only UK nationals who were bewitched by the show: tennis star Mark Philippoussis’ Greek father is said to have come to Australia after seeing an episode of Skippy.[9]See ‘Making His Mark’, The Age, 6 July 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/tennis/making-his-mark-20030706-gdvzxk.html>, accessed 18 May 2020.

The show also featured some powerful representations of Aboriginality for the era, as in the episode ‘They’re Singing Me Back’, about an Aboriginal girl (Candy Devine) torn between two cultures; or the two-parter ‘Tara’, about an Aboriginal elder (Ali Miller) who succumbs to a strange spiritual affliction and must be exorcised by the songmen of his own tribe. While these ‘white-on-black’ representations inevitably fall into stock assumptions and tropes – including that of the noble savage, which Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal filmmakers have long wrestled with[10]See Frances Peters-Little, ‘“Nobles and Savages” on the Television’, Aboriginal History, vol. 27, 2003, pp. 16–38. – they rebut the ‘doomed race’ idea,[11]For more on this historical phenomenon, see Russell McGregor, Imagined Destinies: Aboriginal Australians and the Doomed Race Theory, 1880–1939, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1997. and show Aboriginal dance and ritual to be part of a living, breathing culture. This was a reflection of the ethos of Robinson, who had the utmost respect for Aboriginal people and their culture. Reflects Bonner, ‘In the various episodes that featured Australia’s First People, they were always treated with great regard and sensitivity [… in terms] of subject, story and spirituality.’ And as for Miller’s performance as Tara, James is effusive: ‘When the camera was on him, he had such presence […] He could have been a [professional] actor.’ It would of course be absurd to ask that Skippy, or any television show, somehow transcend history, politics and culture. But, on balance, the show helped usher in a more enlightened view that acknowledged the birthright connection of Australia’s First People to the land.[12]For a serious (and more nuanced) discussion of the program’s treatment of Aboriginality, see my forthcoming chapter ‘Skippy the Bush Kangaroo: Idealism, “Reality” and 1960s Australian Children’s Television’, in Debbie Olson & Adrian Schober (eds.), Children, Youth, and International Television.

After production wrapped up on the show, James went on to play supporting roles in Barrier Reef (Fauna’s follow-up to Skippy) and The Box, before reinventing himself as a celebrity chef. Bonner, who became something of a sex symbol after Skippy (in 1972, he was the first Australian Cosmopolitan centrefold[13]See Tracey Johnstone, ‘International Actor Tony Bonner Connected Closely to Home’, Seniors News, 11 December 2018, <https://www.seniorsnews.com.au/news/international-actor-tony-bonner-connected-closely-/3592169/>, accessed 18 May 2020.), had memorable roles in Money Movers (Bruce Beresford, 1978), Cop Shop and Anzacs, and was later made a Member of the Order of Australia for services to the arts, lifesaving and charities, also receiving several acting awards. Both actors are immensely proud of having been part of Skippy. Bonner best puts the program into historical context:

It’s still the most successful television series made in Australia, and I think it probably always will be. I don’t think any television series in Australia will sell [to] more countries and affect more people in the world than Skippy. It’s iconic, [and] it became part of the dialogue of this country – any blue-eyed, fair-headed boy in Australia was called a ‘skip’.

They are dismayed, however, at how the Ranger Headquarters set and surrounds in Duffys Forest, on the fringe of Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park, has gone to rack and ruin. ‘It’s very sad,’ laments James. ‘I’ve been back to the set twice: once for a newspaper shoot, and once when I took my son up there as a little boy, showing him where Daddy used to go to work.’ In 1970, the area was open to the public as a minor zoo, as Waratah Park, ‘Home of Skippy’. It shut its gates in 2006. Sydney’s Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council now owns the former Crown land, and has been working towards restoring the site.[14]See Helen Pitt, ‘Paradise Lost: Sydney’s Forgotten Theme Parks’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 2019, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/paradise-lost-sydney-s-forgotten-theme-parks-20190712-p526pc.html>, accessed 18 May 2020. As an early purpose-built television set in Australia (with sliding walls to facilitate camerawork), the Ranger Headquarters is an important cultural artefact, and Bonner muses that ‘it’s a shame [it] can’t be dismantled, taken to some piece of council or government land and just rebuilt, and be used as a living exhibition’. If the site is not saved soon, it will be a tragic loss to Australian television history.

Special thanks to Mr Philip Austin, co-chairman of Fauna Productions, for his permission to reproduce the images for this article.

Endnotes

| 1 | For detailed accounts of early children’s television in Australia, see Brian Davies, Those Fabulous TV Years, Cassell Australia, North Ryde, NSW, 1981; Brendan Horgan, Radio with Pictures! 50 Years of Australian Television, Lothian, Sydney, 2006; and Andrew McKay, ‘Kids’, in Peter Beilby (ed.), Australian TV: The First 25 Years, Nelson & Cinema Papers, Melbourne, 1981, pp. 122–33. |

|---|---|

| 2 | John McCallum, Life with Googie, Heinemann, London, 1979, pp. 232–3. |

| 3 | See Don Storey, ‘Skippy’, Classic Australian Television, 2013,<https://www.classicaustraliantv.com/Skippy.htm>, accessed 18 May 2020. |

| 4 | McCallum, op. cit., p. 232. |

| 5 | Russell Clark, ‘Multi-million Dollar Marsupial’, TV Times, 6 January 1971, p. 8. |

| 6 | See Dianne Butler, ‘Skippy Hits the Spot with Frank Packer’, The Courier Mail, 17 September 2009, <https://www.couriermail.com.au/news/skippy-hits-the-spot-with-frank-packer/news-story/153b3c22d97051cfce1fff9eebfd41a2>; and David Knox, ‘Is This Our Oldest TV Show to Still Be in Reruns?’, TV Tonight, 5 May 2016, <https://tvtonight.com.au/2016/05/is-this-our-oldest-tv-series-to-still-be-in-reruns.html>, both accessed 18 May 2020. |

| 7 | Skippy: Australia’s First Superstar, DVD, DV1, 2009. |

| 8 | ibid. |

| 9 | See ‘Making His Mark’, The Age, 6 July 2003, <https://www.theage.com.au/sport/tennis/making-his-mark-20030706-gdvzxk.html>, accessed 18 May 2020. |

| 10 | See Frances Peters-Little, ‘“Nobles and Savages” on the Television’, Aboriginal History, vol. 27, 2003, pp. 16–38. |

| 11 | For more on this historical phenomenon, see Russell McGregor, Imagined Destinies: Aboriginal Australians and the Doomed Race Theory, 1880–1939, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1997. |

| 12 | For a serious (and more nuanced) discussion of the program’s treatment of Aboriginality, see my forthcoming chapter ‘Skippy the Bush Kangaroo: Idealism, “Reality” and 1960s Australian Children’s Television’, in Debbie Olson & Adrian Schober (eds.), Children, Youth, and International Television. |

| 13 | See Tracey Johnstone, ‘International Actor Tony Bonner Connected Closely to Home’, Seniors News, 11 December 2018, <https://www.seniorsnews.com.au/news/international-actor-tony-bonner-connected-closely-/3592169/>, accessed 18 May 2020. |

| 14 | See Helen Pitt, ‘Paradise Lost: Sydney’s Forgotten Theme Parks’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 14 July 2019, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/paradise-lost-sydney-s-forgotten-theme-parks-20190712-p526pc.html>, accessed 18 May 2020. |