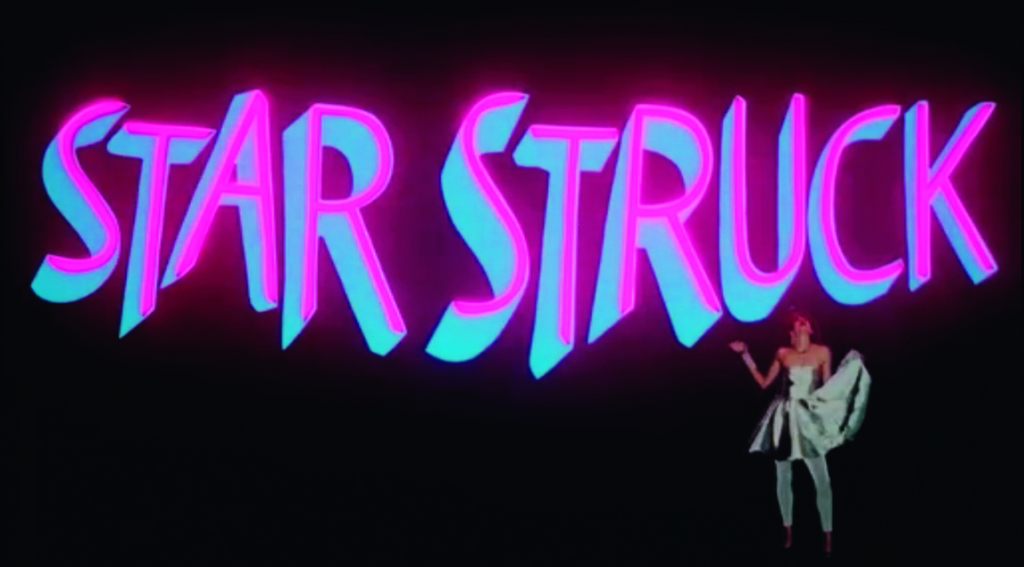

A teenage punk rocker dangles from a tightrope between two Sydney skyscrapers, journalists and bystanders ogling nervously from the ground below. She’s wearing a rainbow cape, a yellow leather harness and two humungous, scene-stealing prop breasts. This madcap scheme – yes, it’s planned – is the brainchild of her fourteen-year-old cousin Angus (Ross O’Donovan), who’s also her manager. The aim: a spot on the evening news, a naive, last-ditch attempt at musical stardom. The singer is Jackie Mullens, played by the indomitable Jo Kennedy in her feature debut. The film is Starstruck (1982), Australia’s first rock’n’roll musical, directed by Gillian Armstrong three years after My Brilliant Career (1979), the stunning success that shot her to industry fame and instantly onto the top rung of Australian film directors.

That a cinematic work as raucous and unabashedly fun as Starstruck has been largely forgotten by the public is as much due to marketing and distribution difficulties as it is to the many strange and sometimes confusing frictions that the film presents us. It trades out the trendy, identity-prodding analyses of its contemporaries – Breaker Morant (Bruce Beresford, 1980) and Gallipoli (Peter Weir, 1981) – for aesthetics and attitude, and yet many at home deemed it simply too Australian for wider appreciation. It is kitschy and at times chaotic, recontextualising the musical form as a cartoonish music-video extravaganza, but its bare-bones narrative is borrowed from a simple Hollywood formula as old as sound cinema itself. On occasion, Starstruck seems in conflict with its own parts: between its brassy, scene-stealing protagonist and her bratty male sidekick, both vying for the film’s spotlight; between its director, whose personal stake in the project was her reputation as a distinctly feminist voice in cinema, and its writer, a musicologist and Hollywood obsessive whose upbringing is largely the stimulus for the screenplay.

Few of these conflicts compromise the film; rather, they enhance it in odd and unexpected ways. Though it was a local success at the time of its release, some of Starstruck’s eccentricities complicated its commercial rollout and have since stifled its longevity, making it overdue for a critical and commercial reconsideration that doesn’t solely and simplistically frame it as an achievement for women’s filmmaking in Australia, an auteurist position that severely underplays the equally significant contributions of screenwriter MacLean, lead actor Kennedy and the production’s immensely talented team. This is to say nothing of Armstrong’s own skills as collaborator and adaptor, which enabled her to swerve dramatically and unexpectedly from the course that many expected her to follow after the success of My Brilliant Career.

Putting on a show

Starstruck follows three simple, familiar narrative strands. The first involves Jackie’s pursuit of stardom: her hit performance at the Lizard Lounge, a red-lit late-night venue, has given her a taste for more. Angus devises the aforementioned tightrope stunt to get the attention of Terry Lambert (John O’May), a television presenter who hosts the Countdown-esque The Wow! Show. She books a slot, but, in a moment of individualistic abandon (or perhaps diva-dom), ditches her band, The Wombats, and its guitarist, love interest Robbie (Ned Lander), opting for a stripped-back performance that flops on live television. The second strand follows Jackie’s romantic escapades. We see her early in the film rolling about in bed with Robbie, but it’s Terry who really catches her eye. After she falls from her tightrope and into the latter’s arms, the two seem relatively smitten, but it’s only later, in a moment of musical kitsch perfection when she realises that Terry is gay, that she comes to see what she had in the first place with Robbie. The final strand gives the film its propelling force: Jackie’s mother, the glamorous pub proprietor Pearl (Margot Lee), is told by the brewery that owns the Harbour View Hotel that she must pay arrears in rent or immediately foreclose. Angus’ deadbeat dad, Lou (Dennis Miller), briefly romances Pearl but soon takes off with the pub’s money, which Pearl is depending on for her business to survive.

These strands come to an exhilarating head in the film’s final scenes, which take place inside and around the Sydney Opera House. The Wow! Show runs a talent contest on New Year’s Eve, the grand prize for which is A$25,000. Jackie, Angus and The Wombats sneak in dressed as a television crew, storming the stage just in the nick of time to perform ‘Monkey in Me’ in front of an electrified crowd. Terry crowns Jackie the winner, and she becomes an instant star, saving the pub. Angus is thrown out but locks eyes with a girl on the Opera House’s deserted steps; the film’s concluding moments see them rolling around kissing as fireworks explode across the harbour.

Hailed, amusingly, as Australia’s ‘first ever proper musical’,[1]Adrian Ryan, ‘Starstruck: A Conversation with Gillian Armstrong’, Roadrunner, vol. 5, no. 4, May 1982, p. 14, emphasis in original. Starstruck is a modern punk tale with unlikely origins, its barmaid-makes-good story inspired by one of American cinema’s most wholesome genres. MacLean unabashedly admits the influence of the Arthur Freed–produced Mickey Rooney – Judy Garland MGM films[2]See Karina Longworth, ‘Judy and Mickey’, Slate, 30 October 2015, <https://slate.com/culture/2015/10/the-mgm-history-of-judy-garland-and-mickey-rooney.html>, accessed 9 August 2019. in which the famously charming musical duo would ‘put on a show’ to resolve the film’s central conflict.[3]Stephen MacLean, in the featurette Screenwriter Reflects, Starstruck, DVD, Blue Underground, 2005. Take Strike Up the Band (Busby Berkeley, 1940), which has all the same elements as Starstruck: a fundraising mission; two chirpy, ambitious young talents who will stop at nothing to be seen and heard; and a sweet, tidy resolution that could only take place in the movies. While other Australian films of the time could be said to fit a vague genre mould – The Man from Snowy River (George Miller, 1982)is a western, Gallipoli is a war film – few other local titles produced in the early 1980s used a classic formula quite as brazenly as Starstruck did, and certainly none disguised it behind a modern sheen of colour and music quite as well.

Unlike its British and American counterparts, the booming Australian film industry had no operative studio or star system at the time of Starstruck’s production, with the industry only beginning to enjoy the first fruits of its new wave. Filmmakers emerged from schools and universities, and films were funded by government bodies and private investors. When MacLean’s script called for two fresh-faced actors to front it – his own ‘Mickey and Judy’ – there were no studio screen tests to cherrypick from. The casting of Starstruck involved a nationwide ‘search for a star’–style audition process that culminated in Melbourne, where finalists were being paired up for on-screen chemistry tests.[4]Greg Flynn, ‘Star Strikes It Lucky’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 15 July 1981. How newcomers Kennedy and O’Donovan scored the roles of Jackie and Angus was called by co-producer Richard Brennan ‘a full-frontal assault on the casting process’.[5]Richard Brennan, commentary, Starstruck, DVD, op. cit. In an attempt to replicate the behaviour of the characters they were auditioning to play, the two stormed the audition room holding a fire hose, screaming, ‘There’s a fire!’ Armstrong loved the approach, seeing kernels of Jackie and Angus in the pair’s eccentric stunt, and they were cast.[6]David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 148.

Kennedy gives a wonderfully zany, naive performance as Jackie, using her untrained charm and reactive, unselfconscious pure energy to channel her character’s bravado. Starstruck is less cut-and-dry feminist than My Brilliant Career in that Jackie seems unhindered by her gender: it’s never directly referenced as a roadblock to her success, and, indeed, she tends to use it to her advantage. Her elaborate presentations – her Wilma Flintstone hairdo in her first performance, the fabulously gaudy tulle costume she wears in the finale and the aforementioned fake breasts being perfect examples – catch eyes, but it’s her moxie that sells the film’s unlikely rags-to-riches story, a courage that Kennedy brings to the role in spades. O’Donovan was seventeen during Starstruck’s filming, and that maturity shines through in his depiction of the fourteen-year-old: Angus may be a chronic troublemaker and school-wagger, but he is whip-smart, is keenly interested in women notwithstanding his total inexperience (‘She’d be good for a shag,’ he says about a female shopfront mannequin) and has business savvy. Despite such promise, it would be O’Donovan’s only major screen role.

The film is also aided by a secondary cast of oddball character-actors who bring the Harbour View Hotel to life with quirk and colour. Pat Evison plays Nana, a plump, cheeky caretaker who whips the misbehaving Angus into shape. Max Cullen is Reg, who sits seemingly permanently at the pub counter, a talking pet cockatoo affixed to his shoulder; his look later inspires The Wombats, who perform in the film’s finale with fake cockatoos atop their blazers. And Norman Erskine plays burly local Hazza, who is seen taking care of the riffraff when things get out of hand during a pub celebration. These small but significant contributions give Starstruck its heart and soul.

A tale of two cities

Starstruck is inconceivable without Sydney, the city’s visual iconography permeating the film. Wide exteriors, often used simply as part of scene transitions, work as constant visual signposts of location, which then stream indoors, where the city’s landmarks are woven into interior sets with a cheeky, kitschy eye. A mosaic mural of the Sydney Harbour Bridge fills a wall of the Harbour View Hotel, the pub itself sitting at the south pylon of the actual bridge, its walls shaking as trains run above it. Early in the film, Jackie cosies up with Robbie on a sun bed, the waves of Bondi Beach crashing behind them. Later, we’re invited into Jackie’s bedroom, her walls plastered with scaled-down images of the same beach; inside, an ironing board becomes a surfboard and Jackie’s bed is a paddling pool, as if a Ken Done mural had suddenly come to life. Indeed, the first footage for the film – shot by Brennan long before the budget had been secured – was of Sydney’s iconic New Year’s Eve fireworks at the advent of 1981.[7]Brennan, op. cit.

It comes with some surprise, then, to learn that Starstruck was birthed by MacLean in the vibrant pub scene of Australia’s more ‘serious’ cultural capital, Melbourne. Once a precocious young music journalist, MacLean met co-producer David Elfick through the now-shuttered music magazine Go-Set in the late 1960s, when Elfick ran the magazine’s Sydney edition. Reuniting with the producer years later in London for the launch of Newsfront (Phillip Noyce, 1978) – Elfick’s earlier producing success – MacLean charmed Elfick with stories of his childhood experiences at the Newport Hotel, a colourful pub in suburban Melbourne, where his mother worked. ‘I thought it would be great to do an Australian musical, and I coined the title, Starstruck,’ recalls Elfick. ‘I gave him all my spare travellers’ cheques [£300 worth[8]Paul Byrnes, ‘David Elfick’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/people/David_Elfick/portrait/>, accessed 21 August 2019.] and said: “Write a script!”.’[9]David Elfick, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 147.

Why Starstruck’s story was transplanted to Sydney is a question of sensibility. MacLean had moved from Melbourne to the New South Wales capital in 1971 and lived near Bondi Beach, perhaps finding levity in Sydney’s more festive atmosphere and beachy climate. MacLean’s cultural leanings give us some indication: a long-time student of Hollywood and an ‘amateur musicologist’,[10]Julie Clarke, ‘Starstruck Boy from Oz Made It’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 May 2006, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/starstruck-boy-from-oz-made-it-20060502-gdngpg.html>, accessed 21 August 2019. the writer seemed to favour style and humour over seriousness and cool. In one interview about Starstruck, he reprimands the affected intellectual superiority of Melbourne’s middle class, placing it in a spectrum: ‘Toorak “quality” culture at one end, Carlton “alternative” at the other’.[11]Stephen MacLean, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘Scott Murray Talks to Screenwriter Stephen MacLean’, Cinema Papers, issue 37, April 1982, p. 112. Best known as the author of The Boy from Oz, the Peter Allen biography that served as the foundation for Australia’s best-known musical, and a friend to such icons as Peggy Lee and Allen himself,[12]Clarke, op. cit. MacLean was blessed with a cultural life that was channelled in his Starstruck script and lent itself naturally to Sydney’s sense of scale, playfulness and symbolism, a clean break from the self-importance that Melbourne is sometimes seen to represent.

Further traces of MacLean’s life, beyond the city in which Starstruck is set, can be found in the character of Angus, based on a boy named Andrew Kennedy whose mother ran the Newport Hotel.[13]MacLean, in the featurette Screenwriter Reflects, op. cit. Although Jackie is very much the protagonist of Armstrong’s film, it’s through Angus’ perspective – sometimes hagiographic, sometimes jealous, sometimes intensely critical – that she’s viewed. It’s his grand scheme that lands Jackie front and centre on the nightly news, and, when Jackie flounders on The Wow! Show, it’s because she has gone against Angus’ better judgement. Jackie’s lesson is to learn to trust her cousin despite his age and apparent immaturity. ‘It’s the boy’s story,’ MacLean remarks in a featurette included in the film’s 2005 DVD re-release, somewhat bitterly. ‘I think that was lost.’[14]ibid. In one sense, it actually was: when recutting the film for international audiences, the opening scene depicting Angus having a dream that prophesies his future as a producer was excised.[15]Camille Scaysbrook, ‘Starstruck’s Lost Sequence’, <https://starstruck1982.weebly.com/production.html>, accessed 21 August 2019. In it, Angus finds himself at a lit-up school desk in a dark room, quizzically scanning the various occupations scrawled in white paint on its black walls and floor. One by one, celebrity impersonators jump through the walls as The Swingers play the title song. At the end of the scene, Angus’ destiny reveals itself: he drives a tractor through the back wall to reveal ‘Angus Mullens Presents’ in neon lights, with Jackie subsequently appearing in an old-fashioned gown and wearing pearls.

‘That little something extra’

The Australian film industry was prospering significantly during Starstruck’s pre-production. The 10BA tax concession had come into full effect by the early 1980s, coaxing private investors to pour money into local productions – thirty-three films were made in Australia in 1982, up from twenty-two in 1981 and fifteen in 1980[16]Stratton, op. cit., p. 3. – and Starstruck was one of the first projects to reap the financial benefits.[17]ibid., p. 147. Elfick and Brennan had previously had a hit with Newsfront and hoped to duplicate its success. Thanks to contributions from the Australian Film Commission and a slew of private funders, A$1.75 million was secured for the production, a budget that later ballooned to A$2.5 million.[18]Brennan, op. cit. Once MacLean’s script had been developed, they set out to find a director who would suit its tone.

In the film, Jackie and Angus define stardom as ‘that little something extra’, a line written by MacLean as a throwback to George Cukor’s 1954 iteration of A Star Is Born, in which James Mason’s Norman uses the same phrase to describe Garland’s Esther, who is on the verge of achieving fame. It might also be used to describe what eventual director Armstrong contributed to the film, and that’s not all that Garland and Armstrong have in common: a glamorous pair of shoes took Garland out of Oz, and fabulous footwear similarly brought Armstrong to Starstruck. Armstrong had heard about Starstruck in its development stage through The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) director Jim Sharman, a friend of MacLean’s, and was interested in pursuing something radically different from My Brilliant Career: ‘I didn’t want to make another period picture about a woman fighting for her identity,’ she later said. ‘I wanted to do something completely different.’[19]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 147. Having been offered a slew of Hollywood productions, she opted instead to take on another local production, as she recounted to Roadrunner in 1982:

I’d be crazy to do that at this stage [of my career]. Films are teamwork, and I’m only [as] good as the people around me. I couldn’t hope to walk into a strange situation and do as well. I’m still learning […] I’ve talked to a lot of American film makers and we have much more creative freedom over here.[20]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Ryan, op. cit. p. 14.

It was fate and a pair of shoes that delivered Armstrong to Starstruck. Elfick had initially rejected her as a directorial choice, dismissing her as a filmmaker who only did ‘boring period pictures’.[21]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in ‘A Shoe In’, The Age, 6 April 1982, p. 2. Having given up hope, she ran into MacLean at a party, at which she was wearing a pair of blue suede high-heels. ‘He told me “anyone who wears shoes like that should be able to make the movie”. I got the job.’[22]ibid., p. 2.

Despite the success of the end result, the matter of whether Armstrong fulfilled MacLean’s expectations for his script is doubtful. Upon the film’s restoration, O’Donovan told the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) that

the Starstruck you saw on screen was not the Starstruck that Stephen MacLean wrote. The plot that Stephen wrote centred around my character, Angus, while the film that Gillian Armstrong made was centred around Jo’s character, Jackie. Gillian got him to twist aspects of the plot which was great because she created a new story.[23]Ross O’Donovan, quoted in Miguel Gonzalez & Adam Blackshaw, ‘Ross O’Donovan Beyond Starstruck’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/ross-odonovan>, accessed 21 August 2019.

If Armstrong did make sizeable changes to MacLean’s script, they were decisive: Starstruck makes no apologies about its focus on Jackie’s selfish and simple-minded desire to be famous, and the resulting work is all the better for it. With Jackie placed front and centre, Armstrong’s film could lean more decisively into Jackie’s world, one in which she hovers somewhere between reality and the stars.

If Starstruck can be seen now as the progenitor of a kitsch-pop style of filmmaking that would define Australian cinema in the 1990s – evident in Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992), Muriel’s Wedding (PJ Hogan, 1994) and The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott, 1994) – that is, in many ways, thanks to the team that Armstrong and her producers assembled for it. Cinematographer Russell Boyd had worked previously on Picnic at Hanging Rock (Weir, 1975), The Last Wave (Weir, 1977) and Gallipoli, and brought a palpable liveliness to Starstruck’s wacky world, his experience with action aiding the film’s fast-paced style and success-driven plot. Starstruck’s production designer was Brian Thomson, who was then most famous for having designed the original Rocky Horror Show and its film adaptation, and his sense of otherworldly kitsch can be seen in Starstruck’s often-breathtaking indoor locales, which are attended to down to their minutest details (Angus’ Elvis Presley wallpaper, the pub’s linoleum benches and tacky white tiles). Luciana Arrighi designed the majority of the film’s costumes, but was unable to complete the costumes for the Lizard Lounge sequence due to other commitments, passing that responsibility on to collaborator Terry Ryan. Arrighi and Boyd both went on to win Academy Awards: Arrighi for her production design on Howards End (James Ivory, 1992), and Boyd for the cinematography of Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (Weir, 2003).

From ‘a costumer’s dream’ to ‘a star is stillborn’

The general perception of Starstruck, as with most other so-called forgotten classics, is that it did poor business locally and was dismissed – or, worse, panned – by critics. In reality,the film performed reasonably well at the local box office, making A$1.54 million,[24]See Film Victoria, Australian Films at the Australian Box Office, 2009, p. 21. and sold a comparable number of tickets to other Australian arthouse hits like Jocelyn Moorhouse’s Proof (1991) and Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978).[25]Brennan, op. cit. The reviews of the film were not bad; in fact, many were supportive (if a little ambivalent). The most effusive praise came from The Age’s Neil Jillett, who called Starstruck ‘a brilliant bombshell of a film, perhaps the first satire thrown up by the Australian cinema’s New Wave’. Jillett was also one of the few critics to give Armstrong credit for imbuing the film with some serious meaning, calling Starstruck a ‘rather alarming record of the values which this country holds most dear’.[26]Neil Jillett, ‘Starstruck Is Armstrong’s Brilliant Satire’, The Age, 12 April 1982. Conversely, the Adelaide Advertiser’s Terry Jennings ‘came away feeling awfully old and distanced from the general hubbub’.[27]Terry Jennings, The Advertiser, 10 April 1982. In his 1990 overview of Australia’s cinema boom, The Avocado Plantation, David Stratton called the film ‘ultimately endearing’, but noted, in his typically fusty way, that ‘[t]he abundance of musical numbers tends to overwhelm the slight plot; a nude love scene is totally unnecessary; and a ghastly scene of gay men in a swimming pool with plastic sharks represents a low point in Australian cinema’.[28]Stratton, op. cit., p. 150. And, in the 1995 critical compendium Australian Film 1978–1992, Anna Gul calls it a ‘disappointing and gaudy musical comedy’ with a ‘gappy storyline’.[29]Anna Gul, ‘Star Struck’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Film 1978–1992, Oxford University Press. Oxford, 1993, p. 112.

Matching the praise for My Brilliant Career while also subverting the critical perception of her past work by taking on an unexpected project was a daunting dual task for Armstrong, who resented that many critics could only analyse Starstruck by drawing parallels between it and her earlier work.[30]Gillian Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, Starstruck, DVD, op. cit. Take, for example, Debi Enker, who, writing for Cinema Papers, said that Starstruck was

concerned with the themes and relationships that its director, Gillian Armstrong, has proved to be familiar with, and adept in portraying: a woman’s dreams and aspirations; her efforts to realize them in a personal sense and through her relationships; and the contrasting environments that her quest for recognition creates.[31]Debi Enker, ‘Starstruck’, Cinema Papers, issue 37, April 1982, p. 166.

When boiled down, this almost humorously broad portrayal of Armstrong’s directorial raison d’être could be applied to any number of films and stories about women, and the same assessments were certainly not being levelled at male directors who had made multiple films about male protagonists.

Starstruck makes no apologies about its focus on Jackie’s selfish and simple-minded desire to be famous … With Jackie placed front and centre, Armstrong’s film could lean more decisively into Jackie’s world, one in which she hovers somewhere between reality and the stars.

Overseas, the film’s critical reception was similarly spotty. The New York Times’ Janet Maslin pinpointed the superficial similarity between Starstruck’s Jackie Mullens and My Brilliant Career’s Sybylla Melvyn (Judy Davis) – each is ‘a red-haired heroine with decidedly headstrong ways’ – but went on to call the 1982 film ‘a costumer’s dream’, ‘dizzy, impudent, highspirited’ and ‘an original’[32]Janet Maslin, ‘Starstruck Down Under’, The New York Times, 10 November 1982, p. 26. in a review that could justifiably be described as a publicist’s dream. The piece by The Boston Phoenix’s Alan Stern, however, wore its opinion on its headline: ‘A star is stillborn’.[33]Alan Stern, ‘A Star Is Stillborn’, The Boston Phoenix, 8 March 1983, p. 66. What turned some critics off the film seems to have been a general suspicion of its cartoonish, broad appeal in light of the fact that it was directed by someone whom most considered to be a serious, sedate and more overtly feminist filmmaker. Certainly, that suspicion had gendered undertones. Of My Brilliant Career’s strong performance,Armstrong has reflected:

The success of a film is so much to do with timing, and we fluked that. At the time it came out in America there was a great interest in women in film, and that was part of it. And there was already a critical interest in Australian films. And all those critics felt so guilty about being sexist for all those years that they overpraised it, I feel.[34]Armstrong, quoted in Ryan, op. cit., p. 14.

If timing is everything, Starstruck may have missed a beat or two: released around a year into MTV’s first broadcasts, the film attempted to tap into a teen consciousness that was becoming engrossed in music-video culture, but it narrowly failed to ride a wave of overseas interest in Australian music that, according to Armstrong, gained traction only six months after the film’s release.[35]Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. The film’s soundtrack, in turn, had caused problems during pre-production and put huge constraints on the budget. After disagreements over the musical tone of the film, Starstruck’s original music producer resigned, meaning the songs were one of the final elements to be locked down. Due to this, choreography was rushed and crews were left waiting on set.[36]Stratton, op. cit., p. 148. Adding insult to injury, the film’s marketing strategy was stifled when its music videos were rejected from Australia’s TV airwaves.[37]See ibid., p. 150; and Barbara Hooks, ‘Battle over Censorship’, The Age, 25 February 1982, p. 35. Ironically, Starstruck’s greatest strength – its musical numbers, and the wit and style with which they were put together – became its greatest strife.

Finding the beat

Starstruck was originally conceived by MacLean as a comedy with one musical number, but, after encouragement from Elfick, it became an all-out, full-soundtrack screen musical.[38]Brennan, op. cit. Eventually, Armstrong and her cast and crew would film twelve musical numbers. On the 2005 DVD re-release, there are only eleven, with the aforementioned opening dream sequence cut for the film’s 1982 international release.

Despite its substantial budget and seemingly ideal cast and crew, Starstruck faced a production journey that was not smooth sailing. Most of the conflict on set – usually between Armstrong, Elfick and MacLean – centred on the music, which was cobbled together at the last minute. Finding the songs for the film was the most difficult pre-production roadblock. Submitted tapes were scoured by Armstrong and Elfick to no end. Eventually, music-industry heavyweight Michael Gudinski of Mushroom Records put the crew in touch with Phil Judd, of popular New Zealand rock group The Swingers and formerly of Split Enz, who composed ‘Starstruck’ especially for the film. Thrilled with its quality, Elfick and Armstrong quickly put him to work to create more original songs, two of which – ‘Temper Temper’ and ‘Tough’ – were used in the film.[39]Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. Additionally, an existing Swingers song, ‘Gimme Love’ (previously titled ‘One Good Reason’ and released in 1979), was performed by the group in the Lizard Lounge scene. Judd himself can be seen giving a rendition of the title song in the film’s final scene. The rest of the soundtrack came from other local songwriters, some of whom would go on to achieve massive fame: Tim Finn, of Split Enz and later Crowded House, wrote ‘Body and Soul’; Billy Miller, the energetic ‘I Want to Live in a House’, Angus’ only musical number; and Dennis James Nattrass, ‘It’s Not Enough’ and the finale number ‘Monkey in Me’.

Despite nearing its fortieth birthday, the film captures today’s revived appreciation for camp and obsession with stardom just as it did upon its release – maybe more so.

The musical direction was mostly driven by Armstrong, who had final say on the songs that were to be included. Her decisions were sometimes questioned by MacLean and Elfick, who wanted to turn the film into an insider’s take on the Australian rock world. But Armstrong had different ideas; as Elfick told Stratton:

We had a battle, and Gillian won […] It’s fair enough that she won. At the time, I felt my music background should have scored me a few more points in the decision making: but only one person can direct a film. The deal was that she had control, and that was it. She made a highly original film.[40]Elfick, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 148.

For her part, Armstrong wasn’t prepared for the difficulty of shooting musical numbers, an undertaking completely new to her. With Boyd’s input, the numbers were extensively storyboarded in an attempt to save time on set – yet, even with the appropriate prior planning, a single-camera set-up became too time-consuming and expensive, and, eventually, second and third cameras were introduced, allowing for quicker and more total coverage of each number.[41]Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit.

Structurally, Starstruck can be viewed as a narrative strung together by a series of elaborate music videos, a form that, during the nascent months of MTV, was both groundbreaking and experimental. In a way, Armstrong’s film takes the music video beyond the simple purpose of sales-driven promotion and into the realm of narrative storytelling. Given their inability, in this instance, to promote the film as individual works, the musical numbers instead propel the plot in tandem and provide Starstruck with both levity and gravitas as the narrative calls for.

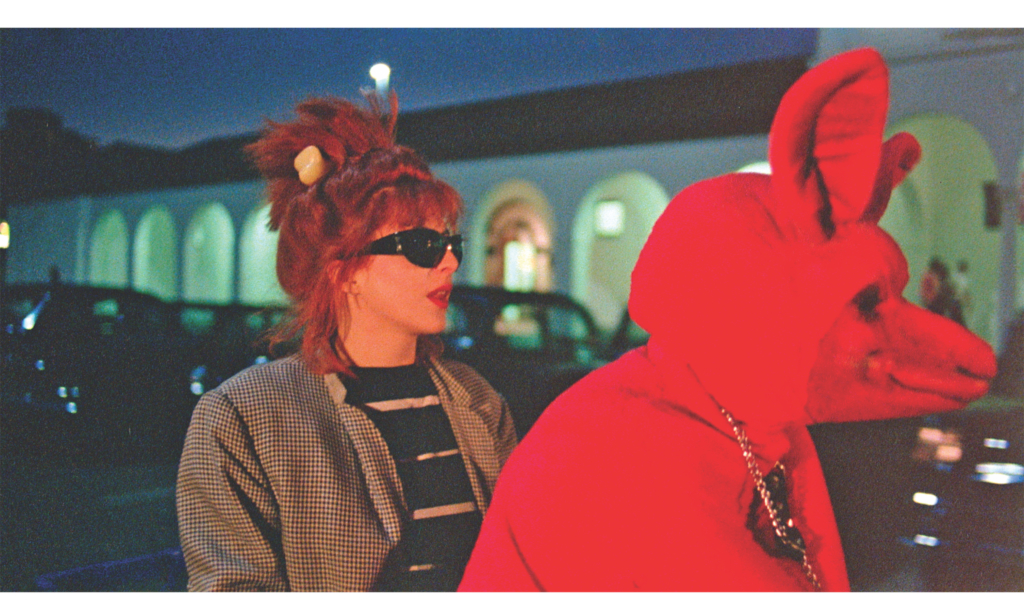

Musical highlights include ‘Temper Temper’, which is the first time we see Jackie perform. She and Angus have just snuck into the Lizard Lounge late at night using an oversized kangaroo costume, which Jackie later appears in on stage and strips from in an Australia-infused nod to Marlene Dietrich’s gorilla striptease in Blonde Venus (Josef von Sternberg, 1932).[42]Jonathan Rayner, Contemporary Australian Cinema: An Introduction, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2000, p. 153. Boyd’s work in the scene is exquisite, the camera rotating rapidly around Kennedy as she performs with an intimidating stare directly into the camera. That same electricity is brought to the finale number, which sees Jackie perform on stage at the Sydney Opera House under a mock Harbour Bridge, wrapped in tulle, the enraptured crowd moving in unison to the beat.

‘Body and Soul’ is sheer musical joy, performed by Jackie and Robbie in the bustling pub after the former’s tightrope stunt. Choreographed by David Atkins, the sequence involves the pub dwellers performing amateur moves as Jackie thrashes atop the bar. ‘Tough’ puts a camp twist on Australian masculinity, revealing Terry’s homosexuality with a sequence that could aptly be described as Esther Williams meets Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (Howard Hawks, 1953) meets the Sydney 2000 Olympics opening ceremony. Real lifesavers wearing old-fashioned swimming costumes perform shoddy synchronised swimming as comical inflatable sharks chase them through a rooftop pool, all while Jackie sings the barely related lyrics in complete turmoil. ‘I Want to Live in a House’ is Starstruck’s most obvious attempt at an outright music video, with its punchy, fast-paced editing and eccentric, high-energy choreography reminiscent of that in Richard Lester’s A Hard Day’s Night (1964) with a touch of Devo and David Byrne thrown in.

The ploy to use these scenes as marketing fodder for the film would eventually backfire. Due to the film’s brief nudity, mild cursing and frank discussion of sexual behaviour, it was rated ‘NRC’ (not recommended for children) by the Film Censorship Board. Following this decision, scenes from the film were then rejected from airing on Australian television before 7.30pm, which is when popular music shows like Countdown – the ABC program that dominated the Australian music scene in the 1970s and 1980s –would air. An appeal was launched by Starstruck’s distributor,Hoyts, but it was rejected by the board in February 1982. Armstrong told The Age that same month:

What upsets us is that clips from NRC or M rated musicals like Grease [Randal Kleiser, 1978], The Rocky Horror [Picture] Show, Fame [Alan Parker, 1980] and Can’t Stop the Music[Nancy Walker, 1980] were shown on those programmes while ours have been banned. We feel we are being victimised […] With any musical it is important for the people to know the tunes before they see it and most hits from musicals are broken on TV. It has been suggested that we make new clips but that would be very expensive and we have no money left. Really, we’ve got to fight this and get the law changed.[43]Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Hooks, op. cit., p. 35.

The complication was never resolved, and this damaged Starstruck’s publicity rollout considerably. But other promotional avenues resulted in significant positive results. Under Mushroom and Gudinski’s guidance, the film’s songs were compiled onto a soundtrack LP that sold well upon release, eventually achieving gold status. Two of the film’s songs charted in Australia: ‘Body and Soul’ broke the top ten on the pop charts, peaking at number five, and ‘Monkey in Me’ also did reasonably well, reaching the number seventy-six spot.[44]Camille Scaysbrook, ‘The Music of Starstruck’, <https://starstruck1982.weebly.com/music.html>, accessed 21 August 2019.

Striking similarities between the character of Terry and Australian music impresario Ian ‘Molly’ Meldrum are no mistake, deriving from MacLean’s and Elfick’s previous relationship with Meldrum at Go-Set before he became a television star on Countdown.[45]David Elfick, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. Like Terry, Meldrum is not only gay but was hugely popular with his teen audience. These similarities perhaps strengthened his interest in becoming involved in the project: Meldrum was an uncredited producer on ‘I Want to Live in a House’ and a vocal advocate for the film. Additionally, redressing the ban on clips from the film being aired, Meldrum invited Kennedy and O’Donovan to guest-host an episode of Countdown, and also had Kennedy and Lander perform ‘Body and Soul’, the film’s hit song, on the program.[46]ibid.

Beyond Starstruck

For years, Starstruck has languished in cultural obscurity. That the 2005 DVD re-release was courtesy of cult film labels Umbrella (Australia) and Blue Underground (US) gives us an impression of the film’s current audience: small, genre-oriented, almost certainly cinephiles. In 2015, a digital restoration of the ninety-four-minute version was completed by the NFSA, and it premiered at that year’s Adelaide Film Festival. In 2017, Starstruck was the oldest title screened as part of a retrospective at the Melbourne International Film Festival titled ‘Pioneering Women’, which celebrated achievements by Australian female directors from the 1980s and 1990s; two days prior to the festival, The Guardian called Starstruck ‘a neon lightning bolt wrapped up in a gaudy tourist tea-towel and decoupaged with love letters to a skewiff memory of Hollywood’.[47]Kate Jinx, ‘Rediscovering Starstruck: Gillian Armstrong’s 80s Rock Musical Extravaganza’, The Guardian, 1 August 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/aug/01/rediscovering-starstruck-gillian-armstrongs-80s-rock-musical-extravaganza>, accessed 21 August 2019. Despite nearing its fortieth birthday, the film captures today’s revived appreciation for camp and obsession with stardom just as it did upon its release – maybe more so. Seemingly begging for new audiences, it remains conspicuously absent on streaming services or as a commonly available, mainstream DVD or Blu-ray, notwithstanding its recent restoration.

Recent events, however, indicate that, like it did for Jackie, the tide seems to finally be turning for the film. New life has arrived for Starstruck, albeit in a different incarnation: following an announcement in September 2018 that the National Institute of Dramatic Art, in partnership with theatre heavyweight RGM Productions, would be developing the story for stage,[48]See ‘Producer of Priscilla – Australia’s Most Successful Theatrical Export – to Launch Revolutionary Approach to Creating a New Australian Musical.’, press release, RGM Productions, 3 September 2018, <https://rgmproductions.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Final-Starstruck-Media-Release-.pdf>; and ‘Starstruck – The Stage Musical Comes to NIDA’, Broadway World, 8 August 2019, <https://www.broadwayworld.com/sydney/article/STARSTRUCK-The-Stage-Musical-Comes-to-NIDA-20190808>, both accessed 21 August 2019. Starstruck – The Stage Musical premiered in late October this year. The production reunites many of Starstruck’s original talents: Elfick is involved, Thomson returned to design the sets and Gudinski made Mushroom Records’ back catalogue available to the creative team, allowing for a freshen-up of the soundtrack.[49]Christie Eliezer, ‘Mushroom Acts Involved in New Starstruck Musical Revival’, The Music Network, 5 September 2018, <https://themusicnetwork.com/mushroom-acts-involved-in-new-starstruck-musical-revival/>, accessed 21 August 2019. Purists might wince at the prospect of drastic alterations amid the story’s transition from screen to stage, but it’s difficult not to be excited by the idea that the same minds that revived Priscilla and Muriel for the stage have given Starstruck the same second life. Starstruck may yet strike again; one only hopes that, when the renewed interest arrives, the film is readily available to take its rightful place in the spotlight.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

Felicity Collins, The Films of Gillian Armstrong, The Moving Image series, no. 6, ATOM, St Kilda, 1999.

Brian McFarlane, Australian Cinema 1970–1985, William Heinemann, Melbourne, 1987.

Scott Murray, ‘Scott Murray Talks to Screenwriter Stephen MacLean’, Cinema Papers, issue 37, April 1982, pp. 111–6.

Jonathan Rayner, Contemporary Australian Cinema: An Introduction, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2000.

Adrian Ryan, ‘Starstruck: A Conversation with Gillian Armstrong’, Roadrunner, vol. 5, no. 4, May 1982, p. 14.

Starstruck, DVD, Blue Underground, 2005.

David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990.

MAIN CAST

Jackie Mullens Jo Kennedy Angus Mullens Ross O’Donovan Pearl Margo Lee Reg Max Cullen Terry Lambert John O’May Robbie Ned Lander Nana Pat Evison Lou Dennis Miller Hazza Norman Erskine

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1982 Length 105 mins (Australia), 94 mins (international) Director Gillian Armstrong Writer / Associate Producer Stephen MacLean Producers David Elfick & Richard Brennan Production Company Palm Beach Pictures Production Manager Barbara Gibbs Cinematographer Russell Boyd Editor Nicholas Beauman Production Design Brian Thomson Art Direction Kim Hilder Set Decoration Lissa Coote & Sally Campbell Costume Design Luciana Arrighi & Terry Ryan

Endnotes

| 1 | Adrian Ryan, ‘Starstruck: A Conversation with Gillian Armstrong’, Roadrunner, vol. 5, no. 4, May 1982, p. 14, emphasis in original. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Karina Longworth, ‘Judy and Mickey’, Slate, 30 October 2015, <https://slate.com/culture/2015/10/the-mgm-history-of-judy-garland-and-mickey-rooney.html>, accessed 9 August 2019. |

| 3 | Stephen MacLean, in the featurette Screenwriter Reflects, Starstruck, DVD, Blue Underground, 2005. |

| 4 | Greg Flynn, ‘Star Strikes It Lucky’, Australian Women’s Weekly, 15 July 1981. |

| 5 | Richard Brennan, commentary, Starstruck, DVD, op. cit. |

| 6 | David Stratton, The Avocado Plantation: Boom and Bust in the Australian Film Industry, Pan Macmillan, Sydney, 1990, p. 148. |

| 7 | Brennan, op. cit. |

| 8 | Paul Byrnes, ‘David Elfick’, Australian Screen, <https://aso.gov.au/people/David_Elfick/portrait/>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 9 | David Elfick, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 147. |

| 10 | Julie Clarke, ‘Starstruck Boy from Oz Made It’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 May 2006, <https://www.smh.com.au/national/starstruck-boy-from-oz-made-it-20060502-gdngpg.html>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 11 | Stephen MacLean, quoted in Scott Murray, ‘Scott Murray Talks to Screenwriter Stephen MacLean’, Cinema Papers, issue 37, April 1982, p. 112. |

| 12 | Clarke, op. cit. |

| 13 | MacLean, in the featurette Screenwriter Reflects, op. cit. |

| 14 | ibid. |

| 15 | Camille Scaysbrook, ‘Starstruck’s Lost Sequence’, <https://starstruck1982.weebly.com/production.html>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 16 | Stratton, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 17 | ibid., p. 147. |

| 18 | Brennan, op. cit. |

| 19 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 147. |

| 20 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Ryan, op. cit. p. 14. |

| 21 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in ‘A Shoe In’, The Age, 6 April 1982, p. 2. |

| 22 | ibid., p. 2. |

| 23 | Ross O’Donovan, quoted in Miguel Gonzalez & Adam Blackshaw, ‘Ross O’Donovan Beyond Starstruck’, National Film and Sound Archive of Australia website, <https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/ross-odonovan>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 24 | See Film Victoria, Australian Films at the Australian Box Office, 2009, p. 21. |

| 25 | Brennan, op. cit. |

| 26 | Neil Jillett, ‘Starstruck Is Armstrong’s Brilliant Satire’, The Age, 12 April 1982. |

| 27 | Terry Jennings, The Advertiser, 10 April 1982. |

| 28 | Stratton, op. cit., p. 150. |

| 29 | Anna Gul, ‘Star Struck’, in Scott Murray (ed.), Australian Film 1978–1992, Oxford University Press. Oxford, 1993, p. 112. |

| 30 | Gillian Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, Starstruck, DVD, op. cit. |

| 31 | Debi Enker, ‘Starstruck’, Cinema Papers, issue 37, April 1982, p. 166. |

| 32 | Janet Maslin, ‘Starstruck Down Under’, The New York Times, 10 November 1982, p. 26. |

| 33 | Alan Stern, ‘A Star Is Stillborn’, The Boston Phoenix, 8 March 1983, p. 66. |

| 34 | Armstrong, quoted in Ryan, op. cit., p. 14. |

| 35 | Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. |

| 36 | Stratton, op. cit., p. 148. |

| 37 | See ibid., p. 150; and Barbara Hooks, ‘Battle over Censorship’, The Age, 25 February 1982, p. 35. |

| 38 | Brennan, op. cit. |

| 39 | Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. |

| 40 | Elfick, quoted in Stratton, op. cit., p. 148. |

| 41 | Armstrong, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. |

| 42 | Jonathan Rayner, Contemporary Australian Cinema: An Introduction, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2000, p. 153. |

| 43 | Gillian Armstrong, quoted in Hooks, op. cit., p. 35. |

| 44 | Camille Scaysbrook, ‘The Music of Starstruck’, <https://starstruck1982.weebly.com/music.html>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 45 | David Elfick, in the featurette Puttin’ on the Show, op. cit. |

| 46 | ibid. |

| 47 | Kate Jinx, ‘Rediscovering Starstruck: Gillian Armstrong’s 80s Rock Musical Extravaganza’, The Guardian, 1 August 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2017/aug/01/rediscovering-starstruck-gillian-armstrongs-80s-rock-musical-extravaganza>, accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 48 | See ‘Producer of Priscilla – Australia’s Most Successful Theatrical Export – to Launch Revolutionary Approach to Creating a New Australian Musical.’, press release, RGM Productions, 3 September 2018, <https://rgmproductions.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Final-Starstruck-Media-Release-.pdf>; and ‘Starstruck – The Stage Musical Comes to NIDA’, Broadway World, 8 August 2019, <https://www.broadwayworld.com/sydney/article/STARSTRUCK-The-Stage-Musical-Comes-to-NIDA-20190808>, both accessed 21 August 2019. |

| 49 | Christie Eliezer, ‘Mushroom Acts Involved in New Starstruck Musical Revival’, The Music Network, 5 September 2018, <https://themusicnetwork.com/mushroom-acts-involved-in-new-starstruck-musical-revival/>, accessed 21 August 2019. |