I have been a diehard fan of US television franchise Survivor since its first season, released nearly eighteen years ago, when Richard Hatch graced the beaches of Borneo completely naked. During the television run of Network Ten’s 2016 reboot of Australian Survivor, however, I became curious as to why this local adaptation wasn’t an enjoyable experience. Was it the casting? Was it just bad luck that most of the contestants who were avid Survivor fans were voted out early? With, at one stage, there being three episodes airing weekly, was it just too much of a good thing? To answer these initial questions, I turn to Doris Baltruschat’s work on media ecologies, particularly her analysis of the localisation of Pop Idol for a Canadian audience.[1]Doris Baltruschat, Global Media Ecologies: Networked Production in Film and Television, Routledge, New York & London, 2010.

Australian Survivor is a localised adaptation of the eponymous long-running American reality-television franchise. Such localisations are a result of international collaborations between production companies and local media ecologies, which consist of media and cultural agents ‘linked through their use of specific production technologies – co-production, format franchising and interactive media’.[2]ibid., p. 5, emphasis in original. The Australian television industry is dominated by format producers, such as the local subsidiaries of Endemol Shine and FremantleMedia, and it is through this type of commercial negotiation that an international format can be adapted for the Australian cultural landscape.

Screening on Channel Ten in the prime-time slots of Sunday, Monday and Tuesday evenings, Australian Survivor faces the challenge of quenching the thirst of fans of the original series, such as myself, without alienating a wider viewership who may be unfamiliar with the strategic complexities of the format. This, I argue, is the key difficulty in adapting an international title for a local media ecology. To explore the challenges inherent in format franchising, this essay will first outline how the US version of Survivor demonstrates narrative complexity. Second, it will look at how the Australian production’s 2016 season was a difficult marriage between textual elements of the original franchise and the demands of Australia’s media ecology. This difficulty in reconciliation resulted in Australian Survivor having to cater for both the fans of the American series and casual viewers newer to the franchise. Ultimately, I argue that narrative complexity is lost when a show has to alter its format for new fans.

The Survivor format

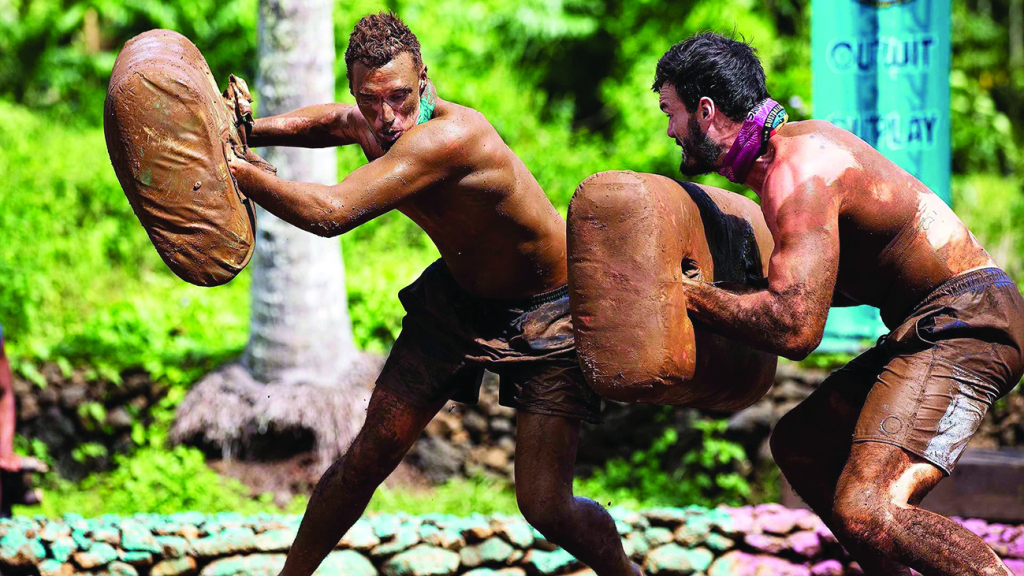

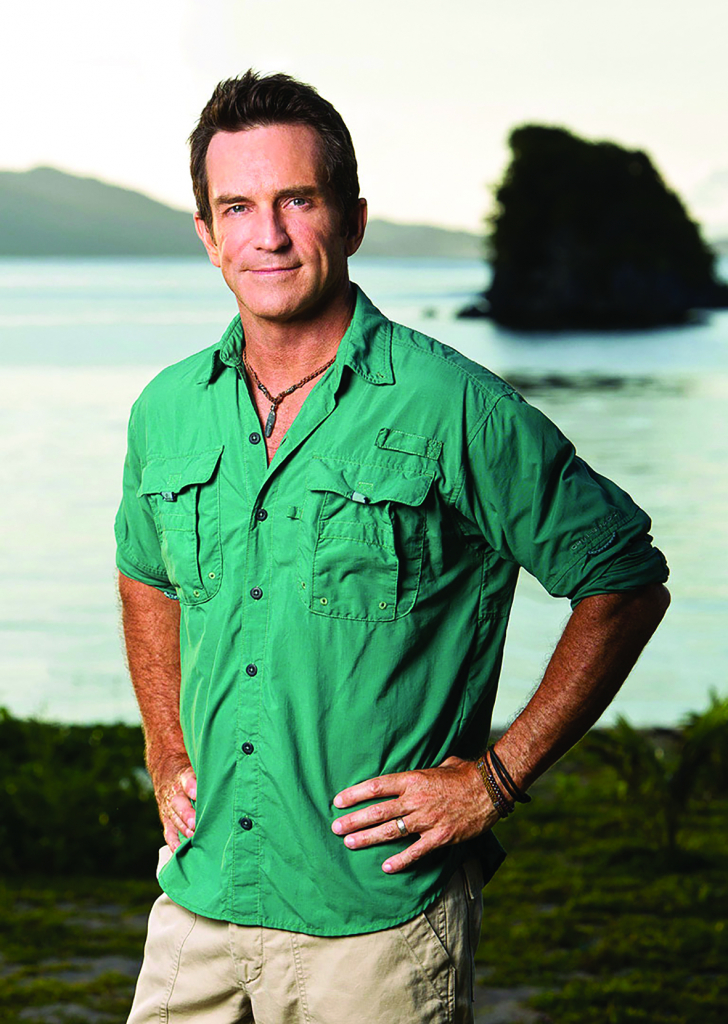

Survivor first premiered in the US in 2000, and has recently wrapped up its thirty-fifth season. An adaptation of the Swedish series Expedition Robinson, it was created by Charlie Parsons, an executive producer on the show alongside Mark Burnett and host Jeff Probst. Each season, a group of sixteen to twenty contestants is stranded in an isolated location; they are divided into two or more teams, referred to as ‘tribes’, which compete for resources and immunity. The tribe that loses immunity must vote off a member at a ‘tribal council’ using a secret ballot. When approximately ten to twelve contestants remain, the tribes are dissolved and contestants compete individually. The final three contestants must face a jury of previously eliminated peers, who determine the ‘Sole Survivor’. The winning contestant receives US$1 million; the runner-up, US$100,000; the third-placer, US$85,000; and so on, with the prize money declining the earlier the contestants are voted out. Each contestant also receives US$10,000 for appearing on the final reunion episode.

Aside from Australia, the show has had forty-eight other international versions, with varying degrees of success. Yet the mass popularity of the Survivor franchise has slowly waned. The first ten seasons of the American series averaged over 20 million viewers, but ratings have been steadily falling: from the twenty-second season onwards, the show has only garnered an audience of between 10 and 13 million. In Australia, however, the American Survivor has been moved to the channel 9Go! following the moderately successful ratings of 2013’s Survivor: Caramoan. The 2016 season of Australian Survivor was itself a moderate success (albeit regularly beaten by the Nine Network’s The Block in viewership); its premiere episode attracted 783,000 viewers in major cities, and its finale, over 1 million.

A wide array of paratextual forms of commentary have developed cult followings among Survivor fans. Once the first jury member has been eliminated, the web series Life at Ponderosa begins; this series follows eliminated contestants after they leave tribal council and reflect on their gameplay at a resort dubbed ‘Ponderosa’. There are several dedicated fan sites as well as forums such as Survivor Sucks that regularly post conspiracy theories and spoilers. Former Survivor: The Amazon contestant Rob Cesternino’s Rob Has a Podcast discusses not just the American Survivor but also other reality shows, including the US version of Big Brother and Australian Survivor. Another popular commentary source is the website Inside Survivor, which tracks contestant gameplay, editing and spoilers for future seasons.

The show has avoided repetition and stagnation through the implementation of themes for seasons, resulting in a quasi-sociological study of American society. Recent themes have touched on class (as seen in the ‘white collar, blue collar, no collar’ season) and on individuals’ supposed biggest gameplay asset (as in the two ‘brains, brawn and beauty’ seasons). Other seasons have divided contestants by age, gender, or whether they are fans of the show or returning favourites, while one season saw returning players compete against their loved ones. Survivor: Cook Islands was perhaps the most controversial season, as it divided contestants by race (white, African-American, Asian and Hispanic). The latest season featured the theme ‘heroes, healers and hustlers’.

Quality and complexity in reality programming

In his seminal work on the topic, Robert J Thompson proposes a list of factors associated with ‘quality television’ (the entirety of which is beyond the scope of this essay); a key aspect of his thesis is that of audience memory. Shows that draw on or cater to audience memory become increasingly self-conscious, especially when referring to their own history:

Though [memory] may or may not be serialized in continuing story lines, these shows tend to refer back to previous episodes. Characters develop and change as the series goes on. Events and details from previous episodes are often used or referred to in subsequent episodes.[3]Robert J Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age: From Hill Street Blues to ER, Syracuse University Press, New York, 1996, p. 14.

As such, while television shows develop a working memory and schema, so, too, does the audience – as seen, for instance, in the mutual use of loaded words and phrases without accompanying explanations. For Trisha Dunleavy, shows of this sort tend towards innovation through noncompliance with standards and expectations.[4]Trisha Dunleavy, Television Drama: Form, Agency, Innovation, Palgrave Macmillan, London & New York, 2009. Once the audience has developed a set of expectations about the form of the show, these can be challenged through repetition and slight variation. Dunleavy’s notion of ‘quality’ is, of course, premised on an adherence to an arthouse cinematic form and narrative structure, whereas, for reality television, a judgement of quality would need to concern format and gameplay structure. I am also inclined to take Jason Mittell’s characterisation of this type of programming as being about differentiations in taste; to him, the term ‘quality television’

is most usefully understood as a discursive category used to distinguish certain programs from others, with such programs less united by formal or thematic elements than used as a mark of prestige to elevate the sophistication of viewers who embrace such ‘quality’ programming.[5]Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling, New York University Press, New York & London, 2015, p. 210.

While the American Survivor, along with many other reality programs, is often denigrated as a product of what Ien Ang calls ‘bad mass culture’,[6]Ien Ang, cited in Tamar Salibian, ‘The Ideology of Mass Culture and Reality Television: Watching Survivor’, The International Journal of the Humanities, vol. 9, no. 10, 2011, pp. 63–70. I argue that it is an example of what I regard as ‘quality reality television’, wherein there is significant narrative complexity and expectations on audiences’ memories. As with most competitive reality television, the audience takes pleasure in hearing Probst’s familiar catchphrases, such as, ‘The tribe has spoken.’ A similar case is evident in Project Runway, in which televisual branding is invoked when mentor Tim Gunn says, ‘Make it work,’ and in America’s Next Top Model, in which presenter Tyra Banks obsesses over the concept of ‘smizing’. Most significantly, RuPaul’s Drag Race has cultivated a slew of dedicated fans who reproduce the show’s lexicon on dedicated social-media channels, most of which build on pre-existing drag culture (as seen in Jennie Livingston’s 1990 film Paris Is Burning).

Likewise, Survivor has developed a considerable schema associated with gameplay strategy, and the show has become increasingly self-referential.[7]Christopher J Wright, ‘Welcome to the Jungle of the Real: Simulation, Commoditization, and Survivor’, The Journal of American Culture, vol. 29, no. 2, June 2006, pp. 170–82. Perhaps the first manifestation of such a schema was the ‘car curse’, which developed over the earliest seasons and was subsequently openly acknowledged in the show. The curse implied that the contestant who would win the car at the final reward challenge would never win the overall title. In Survivor: Guatemala, Probst even informed contestant Cindy Hall of the curse before asking whether she would accept the reward instead of offering the other remaining contestants a car each; she took the reward and was swiftly voted out that episode. Another complex gameplay component is that of the ‘hidden immunity idol’ (HII), which, once found, makes the contestant invulnerable to being voted out if it is played at a tribal council. The HII has enabled a plethora of strategic options that are implicitly acknowledged between text and audience, such as splitting the vote within a dominant voting bloc to ‘flush out’ the idol from an opposing contestant. Yet another term that is used liberally between commentators, fans and contestants is ‘goat’, the origins of which in Survivor lore aren’t entirely known. Commentators have noted that the term is often assigned to female contestants over the age of forty,[8]Josh Forward, ‘Survivor Women: Treatment of the Over 40s’, Inside Survivor, 11 June 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-women-treatment-of-the-over-40s-1481>, accessed 3 November 2017. and denotes a player who would be easily beaten at the final tribal council.[9]Martin Holmes, ‘Survivor History: Origin of the Goat’, Inside Survivor, 24 May 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-history-origin-of-the-goat-685>, accessed 3 November 2017.

The genre of competitive reality television has evolved considerably since Survivor’s first season. The ‘[g]rowth of the international format trade’, argues Baltruschat,

is closely linked to the emergence of new genres, which fall under the broad umbrella of reality TV. Reality TV programs entail hybridized elements from different program categories such as the documentary, soap opera, game show and talk show.[10]I would also add sport to this mix of established genres; see Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 98.

This proliferation embodies a revision of what Richard Kilborn describes as the more ‘serious’ representation of sociohistorical events in content that is produced chiefly for entertainment.[11]Richard Kilborn, Staging the Real: Factual TV Programming in the Age of Big Brother, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2003. I contend that such entertainment-focused reality programming still has the potential to contribute to discourses regarding serious subject matter. RuPaul’s Drag Race regularly engages with contemporary LGBTQIA+ politics, and recent seasons of the American Survivor have had contestants openly talk about domestic abuse, eating disorders, coming out and mental health.

Contestants’ character development plays a significant role in Survivor’s narrative complexity. According to Su Holmes, reality television aims for the ‘articulation of the authentic self’ in order to depict ‘moments of truth’,[12]Su Holmes, ‘“Reality Goes Pop!”: Reality TV, Popular Music, and Narratives of Stardom in Pop Idol’, Television & New Media, vol. 5, no. 2, May 2004, p. 159. while Baltruschat argues, ‘Tele-confessionals in designated video rooms, revelations about conflicts between contestants and individual strategies for winning the game produce intimate accounts of unfolding events.’[13]Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 99. Aside from the voiceover provided by Probst, the contestants themselves act as the narrators of the show, reminding viewers of key narrative information while also allowing the audience to become familiar with the contestants most important to the season’s narrative arcs. In the American Survivor, voiceovers have become increasingly complex, as they regularly recount the detailed strategic implications of losing challenges.

This reliance on audience memory and the heavily serialised nature of the American Survivor speaks to Mittell’s view that narrative complexity avoids reductive and simplistic storytelling:

So what exactly is narrative complexity? At its most basic level, [it] redefines episodic forms under the influence of serial narration – not necessarily a complete merger of episodic and serial forms but a shifting balance.[14]Mittell, op. cit., p. 18, emphasis in original.

Indeed, each season of Survivor consists of several ongoing contestant-centric stories that build over time to a cumulative narrative. While game show–like events are always involved, it is this narrative complexity that sustains audience attention and remembrance. The demands of an audience having a memory are also what separates a show like Survivor from franchises like the Top Model series, which regularly replay key events to aid viewer recollection. When former Survivor contestants return on the show, viewers need to have watched their previous seasons in order to grasp the changing dynamics between contestants. For instance, when Cirie Fields, Amanda Kimmel and Parvati Shallow appeared on Survivor: Heroes vs. Villains after making it to the final three in the earlier Fans vs. Favorites season, only minimal narrative exposition was given to the audience as to their relationship dynamics.

The narrative complexity of Survivor has redefined the episodic format of competitive reality television. Dedicated fans of the American series, I posit, are similar to fans of other complex, quality drama productions, who have a heightened awareness of storytelling mechanics.

Mittell also draws on Seymour Chatman’s work on ‘kernels’ and ‘satellites’: whereas kernels are essential to the cause-and-effect chain of a plot, satellites are peripheral and, thus, can be excluded without rendering the narrative incomprehensible.[15]Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film, Cornell University Press, New York, 1980 [1978], pp. 53–6. Yet the tensions between reality-show contestants provide texture, tone and character depth for dedicated viewers. Pleasure, writes Mittell, can be derived from deciding ‘whether a given event might be a kernel or a satellite in the larger arc of a plotline or series as a whole’.[16]Mittell, op. cit., p. 24.

The narrative complexity of Survivor has redefined the episodic format of competitive reality television. Dedicated fans of the American series, I posit, are similar to fans of other complex, quality drama productions, who have a heightened awareness of storytelling mechanics. This awareness is evident in the nature of the weekly ‘Edgic’ (editing logic) posts on Inside Survivor, in which commentator Martin Holmes compares the visibility of each contestant on the show and whether they are receiving a ‘winner’s edit’.[17]See Martin Holmes, ‘Survivor Edgic – an Introduction’, Inside Survivor, 13 September 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-edgic-an-introduction-3094>, accessed 8 November 2017.

Australian Survivor

An analysis of the adaptation of Survivor for an Australian context allows us to identify whether negative audience reactions are the result of cultural cringe, or whether there were major flaws in the form of the text itself. The challenge for Australian Survivor has been to maintain the diegetic pleasure and formal awareness that define its American counterpart while meeting the demands of the Australian televisual landscape. While the American series would generally produce fourteen weekly episodes of approximately forty-three minutes each, excluding the traditionally longer finale episode, the Australian series consists of twenty-six episodes that range from fifty to ninety minutes, occasionally airing three times weekly. The American version would feature a cast of sixteen to twenty, with attention paid to racial diversity, while the Australian iteration begins with twenty-four contestants; in 2016, the significant majority were white and of a similar appearance. The prize pool is smaller, too, with the winner of Australian Survivor receiving just A$500,000.

To be openly knowledgeable of the American game in Australian Survivor made one a threat, resulting in players who presented as overly strategic being eliminated early.

Even though there have been two seasons ofNetwork Ten’s Australian Survivor reboot to date, awareness of the show’s schema is underdeveloped among the local target audience compared to those watching the American series. Moreover, a significant proportion of Australian contestants have themselves been unfamiliar with the American series, with many expressing discomfort about the ‘backstabbing’ aspect of the game. The inclusion of the HII in 2016, for instance, was accompanied by a lengthy explanation of the rules and strategies associated with the object, and led to an unintended outcome when it made Nick Iadanza a target – not because he had the item, but because possession of it exposed him as a strategic player. In subsequent interviews, Iadanza spoke of how openly being a fan of the show was a significant handicap to his chances of winning the game.[18]Nick Iadanza, in Rob Cesternino, ‘Australian Survivor Finale | Nick Iadanza’, Rob Has a Podcast, 30 October 2016, <http://robhasawebsite.com/australian-survivor-finale-nick-iadanza/>, accessed 3 November 2017. To be openly knowledgeable of the American game in Australian Survivor made one a threat, resulting in players who presented as overly strategic being eliminated early.

Heavy incorporation of sponsors

Reality television has always been an appealing vehicle for new ways to market products to audiences. The Project Runway and Top Model franchises, in particular, employ branded products to enhance contestants’ appearance. Baltruschat draws on Vladimir Propp’s analysis of Russian folktales to articulate how commodities are examples of a ‘magical object’ used to assist characters/contestants on their journeys to a transformed ‘“after” state’;[19]Vladimir Propp, cited in Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 120. that is to say, they achieve their goals through the use of the aforementioned magical objects. In these shows, the dramatic narrative is intertwined with product placement, giving prominence to the exchange value of these items rather than their use value.

This type of integration is a key part of contemporary reality television, and a heavy reliance on sponsorship was evident in the 2016 season of Australian Survivor, which had three A-tier sponsors: Holden, ahm health insurance and Hungry Jack’s. These sponsors played a significant part in reward challenges – particularly the fast-food chain, with extensive segments of contestants exclaiming how much they loved the food. This marketing strategy blurs the episodic boundaries of television. Clips of the show were used in ad breaks, and stills were used on social media, to further promote products – mirroring the approach used by many other Australian reality shows, such as My Kitchen Rules and MasterChef, both of which display extensive Coles branding. While this sponsorship strategy works for shows such as Top Model and Project Runway – the sponsors tend to be fashion-related, meaning audiences can achieve their own transformations using the desired brands – the thematic connection to the brands is lost in Australian Survivor, as the experience can’t be replicated through the consumption of its advertised products.

Challenges of format localisation

There are several issues at play when adapting franchises for local audiences. According to Baltruschat:

Format localization is based on a media ecology, which involves lengthy collaborative processes between the owners of the program, licensee and contracted production crew, who adapt the program for local audiences under the supervision of the original producers.[20]Baltruschat, ibid., p. 120.

The production of a localised text thus requires an acute judgement of what can be considered ‘entertainment value’.[21]Sergio Splendore, ‘Media Logic Production: How Media Practitioners in Italian Reality Television Localize TV Formats and Select “Entertainment Values”’, Journal of Popular Television, vol. 2, no. 2, October 2014, pp. 189–204.

Australian Survivor is a collaboration between Network Ten and the American production company Castaway Television, which offered initial guidance and provided key structures (such as campsites) and challenges. Ten commissioned Endemol Shine to produce a series that would adhere to the structural expectations of its entertainment and factual programming arm, as seen in its other reality titles The Bachelor, The Bachelorette, MasterChef and I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!. As stated above, while its American counterpart screens one hour-long episode weekly (inclusive of advertising breaks), Australian Survivor screens multiple, longer episodes per week. This excessive schedule aligns with the Australian media ecology’s demand for a heavy emphasis on advertising – something that can’t be achieved with only one weekly episode.

A significant component of localising an international format is infusing the series with content familiar to local audiences. Through the inclusion of relevant stories, a local adaptation of a reality show is able to inject itself into ‘the symbolic matrix of national and cultural familiarities’.[22]Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 111. The ostensible Australianness of Network Ten’s 2016 Survivor reboot was particularly evident in the theme of ‘mateship’, which was explored through the lens of masculinity. Sam Webb and Lee Carseldine would often invoke mateship to fight against overly strategic players like Iadanza. Their clichéd expression of Australian identity was also contrasted with the core alliance between Brooke Jowett, Felicity Egginton and Elena Rowland, dubbed the ‘mean girls’ by many fans on social media.[23]Tiffany Dunk, ‘Survivor “Mean Girls” El, Brooke and Flick Defend Themselves Against Angry Viewers’, Herald Sun, 8 October 2016, <http://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/television/survivor-mean-girls-el-brooke-and-flick-defend-themselves-against-at-angry-viewers/news-story/99ff72a76a8272c91f5ce31074e82f40>, accessed 3 November 2017. And it was only at the final tribal council – once she was free from the risk of being voted out – that eventual winner Kristie Bennett revealed her familiarity with the American series.

The progression of reality shows is heavily contrived through carefully placed game twists, however; in spite of their assertion of realism, such programs are accentuated by behind-the-scenes production and economic considerations, which are not always apparent to the viewer. In the case of Australian Survivor, key decisions regarding format have exhibited a lack of foresight by the production team. The American Survivor regularly utilises tribal swaps, merges and double eliminations to keep players on their toes. In contrast, during one reward challenge in the Australian series, the resulting tribal shuffle involved the winning team selecting who they would want to join them from the losing two tribes, with unselected contestants having to merge and form their own new tribe. This reorganisation created a significantly stronger tribe, leading to a complete decimation of the tribe consisting of unselected contestants.

Further consequences of this production decision were the elimination of several stronger strategic players and the birth of a dominant alliance of players who were inexperienced in gameplay. Several members of the latter would then openly admit in confessionals that they did not want to play an overly tactical game, meaning the second half of the season lacked any strategic thrust. This was a significant matter of concern in many reviews of the reboot, in which ‘the stuff that makes […] Survivor great – secrets and lies – [had] played second fiddle to grand speeches about mateship, casual sexism and long shots of men catching fish’.[24]Maeve Marsden, ‘Mean Girls and Mateship: Why Is Survivor So Uncomfortable with Female Alliances?’, Junkee, 10 October 2016, <http://junkee.com/mean-girls-mateship-survivor-uncomfortable-female-alliances/86983>, accessed 3 November 2017. In fact, after the merge, the only tribal council where gameplay came into effect involved the elimination of Jowett, by then a member of the core alliance; this strategy was orchestrated by Egginton, and was promoted heavily in advance. All other eliminations were predictable, as the eliminated contestants were outside the core alliance – an approach that fans of the show call ‘Pagonging’. Coined from the name of a tribe from the American series’ first season, it denotes a dominant alliance purposefully voting out members of another contingent in succession. What this predictability results in is a fairly monotonous season.

To combat the eventual lack of gameplay in that season of Australian Survivor, advertisements had to emphasise potential upsets (or ‘blindsides’, yet another term popularised by the American version and adopted locally) even though they did not eventuate in the actual episodes. One such example was the foreshadowing of ‘Sue’s Big Move’, referring to a potential blindside orchestrated by Sue Clarke. The episodes that followed revealed no such ‘move’ by Clarke, however, and she was voted out in a straightforward manner. Consequently, ‘Sue’s Big Move’ was mocked online. As the Network Ten format requires advertising for events spanning multiple episodes, this case exemplifies a failed attempt to build narrative complexity.

Conclusion

International co-ventures are indicative of trends in the global televisual landscape, with Australian Survivor embodying a considerable challenge for Australia’s media ecology. Network Ten’s other reality shows rarely generate the type of narrative complexity that requires the audience to engage in any memory recall. The dedicated American Survivor viewer, however, relishes the evolution of gameplay strategy and contestant character development, as demonstrated by the successes of paratextual media such as Life at Ponderosa, Inside Survivor and Rob Has a Podcast.

Baltruschat’s study of franchise localisation proposes that a successful adaptation must be not only infused with local content and adherent to the network’s industrial model, but also consistent with the product’s extant format. The biggest challenge faced when localising a complex reality show such as Survivor, then, is how best to cater for both new and old fans. While the latter would want continued variation in and development of the show’s gameplay, more recent audiences would generally be unfamiliar with its strategic elements. The absence of a significant proportion of the American version’s gameplay framework in Australian Survivor therefore resulted in a monotonous experience for many established fans. In order to appeal to a local demographic yet to become acquainted with the franchise, the original’s narrative complexity was sacrificed.

This article has been refereed.

Endnotes

| 1 | Doris Baltruschat, Global Media Ecologies: Networked Production in Film and Television, Routledge, New York & London, 2010. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ibid., p. 5, emphasis in original. |

| 3 | Robert J Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age: From Hill Street Blues to ER, Syracuse University Press, New York, 1996, p. 14. |

| 4 | Trisha Dunleavy, Television Drama: Form, Agency, Innovation, Palgrave Macmillan, London & New York, 2009. |

| 5 | Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling, New York University Press, New York & London, 2015, p. 210. |

| 6 | Ien Ang, cited in Tamar Salibian, ‘The Ideology of Mass Culture and Reality Television: Watching Survivor’, The International Journal of the Humanities, vol. 9, no. 10, 2011, pp. 63–70. |

| 7 | Christopher J Wright, ‘Welcome to the Jungle of the Real: Simulation, Commoditization, and Survivor’, The Journal of American Culture, vol. 29, no. 2, June 2006, pp. 170–82. |

| 8 | Josh Forward, ‘Survivor Women: Treatment of the Over 40s’, Inside Survivor, 11 June 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-women-treatment-of-the-over-40s-1481>, accessed 3 November 2017. |

| 9 | Martin Holmes, ‘Survivor History: Origin of the Goat’, Inside Survivor, 24 May 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-history-origin-of-the-goat-685>, accessed 3 November 2017. |

| 10 | I would also add sport to this mix of established genres; see Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 98. |

| 11 | Richard Kilborn, Staging the Real: Factual TV Programming in the Age of Big Brother, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, 2003. |

| 12 | Su Holmes, ‘“Reality Goes Pop!”: Reality TV, Popular Music, and Narratives of Stardom in Pop Idol’, Television & New Media, vol. 5, no. 2, May 2004, p. 159. |

| 13 | Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 99. |

| 14 | Mittell, op. cit., p. 18, emphasis in original. |

| 15 | Seymour Chatman, Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film, Cornell University Press, New York, 1980 [1978], pp. 53–6. |

| 16 | Mittell, op. cit., p. 24. |

| 17 | See Martin Holmes, ‘Survivor Edgic – an Introduction’, Inside Survivor, 13 September 2015, <http://insidesurvivor.com/survivor-edgic-an-introduction-3094>, accessed 8 November 2017. |

| 18 | Nick Iadanza, in Rob Cesternino, ‘Australian Survivor Finale | Nick Iadanza’, Rob Has a Podcast, 30 October 2016, <http://robhasawebsite.com/australian-survivor-finale-nick-iadanza/>, accessed 3 November 2017. |

| 19 | Vladimir Propp, cited in Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 120. |

| 20 | Baltruschat, ibid., p. 120. |

| 21 | Sergio Splendore, ‘Media Logic Production: How Media Practitioners in Italian Reality Television Localize TV Formats and Select “Entertainment Values”’, Journal of Popular Television, vol. 2, no. 2, October 2014, pp. 189–204. |

| 22 | Baltruschat, op. cit., p. 111. |

| 23 | Tiffany Dunk, ‘Survivor “Mean Girls” El, Brooke and Flick Defend Themselves Against Angry Viewers’, Herald Sun, 8 October 2016, <http://www.heraldsun.com.au/entertainment/television/survivor-mean-girls-el-brooke-and-flick-defend-themselves-against-at-angry-viewers/news-story/99ff72a76a8272c91f5ce31074e82f40>, accessed 3 November 2017. |

| 24 | Maeve Marsden, ‘Mean Girls and Mateship: Why Is Survivor So Uncomfortable with Female Alliances?’, Junkee, 10 October 2016, <http://junkee.com/mean-girls-mateship-survivor-uncomfortable-female-alliances/86983>, accessed 3 November 2017. |