As long there are films, there’ll be films about lone men surviving in nature. Whether these men are forced into such a situation, like the sailor who becomes stranded at sea in All Is Lost (JC Chandor, 2013), or they choose it, like a young romantic’s self-imposed stint in the Alaskan wilderness in Into the Wild (Sean Penn, 2007), the dramatic and mythic appeal of this scenario seems to only increase as our natural world becomes more endangered. Regardless of the circumstances, these tales typically present an archetypal masculine scenario, wherein a solitary male hero must overcome nature through a combination of luck, smarts and sheer physical endurance – with the emphasis usually resting on the latter.

These narrative associations might be front of mind as we watch filmmaker Warwick Thornton arriving at a remote beach in Jilirr, on the Dampier Peninsula in north-west Australia, during the opening sequence of his 2020 documentary series The Beach. Despite shedding his cowboy boots, Thornton is still wearing his black suit and akubra when he plunges cathartically into the ocean on arrival, before setting up shop in the corrugated-tin and timber shack that will be his shelter. He’s certainly come prepared, with his macho, rickety jeep packed to the hilt with all manner of rusty cases and equipment. Also along for the ride are an acoustic guitar, three live chickens and – somewhat incongruously, given the setting – an arsenal of spices, herbs and other ingredients, most of which have been carefully labelled in glass jars. Over the ensuing six half-hour episodes of what he describes as a ‘romantic manly series’ or a ‘romantic blokey film’,[1]Warwick Thornton, quoted in Rochelle Siemienowicz, ‘Warwick Thornton’s Big Time-out at The Beach’, screenhub, 26 May 2020, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news-article/news/television/rochelle-siemienowicz/warwick-thorntons-big-time-out-at-the-beach-260427>, accessed 4 August 2020. Thornton will survive off the land and lead a life of solitude, unseen film crew[2]For the most part, Thornton was accompanied on location by cinematographer Dylan River, sound recordist Nicole Lazaroff and assistant camera operator William ‘Billy’ Wright. See Caris Bizzaca, ‘Warwick Thornton Turns the Camera on Himself’, Screen Australia website, 29 May 2020, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2020/05-29-warwick-thornton-turns-the-camera>, accessed 5 August 2020. notwithstanding.

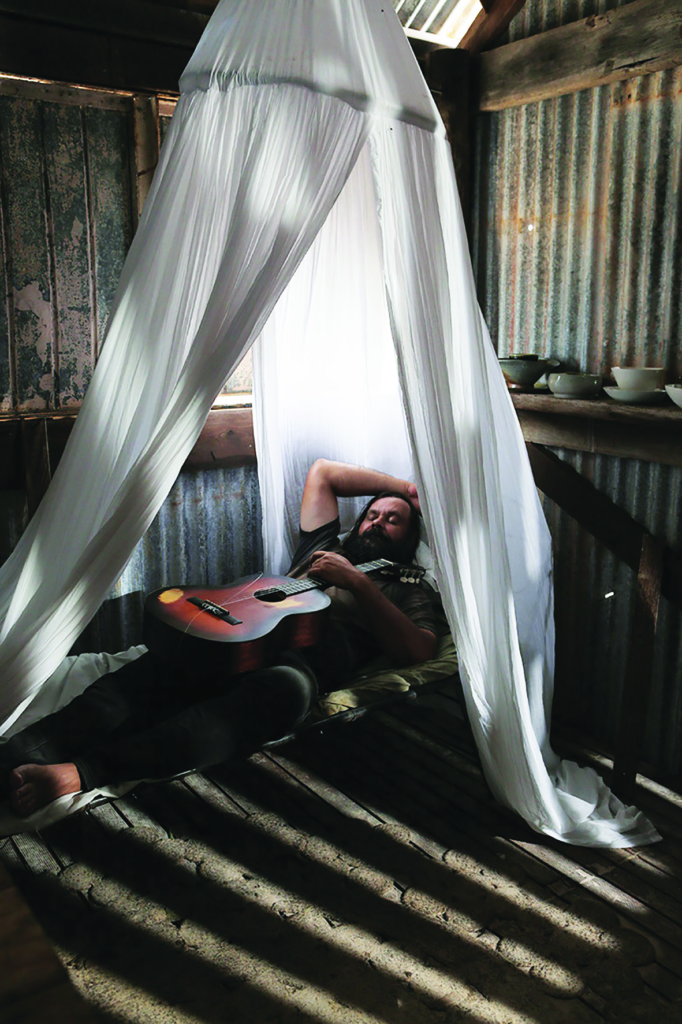

In each episode, Thornton spends some time idling around in the shack, occasionally plucking at his guitar or gazing at the landscape outside. At some stage, he might leave for a leisurely swim, or to take a walk or drive along the coast, showcasing the spectacular Kimberley scenery in the process. He takes full advantage of this land’s culinary offerings – ‘better than a Woolworths’, the director suggests[3]Warwick Thornton, in ‘Warwick Thornton and The Beach’, The Point, 29 May 2020, available at <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/1738543683611/the-point-warwick-thornton-and-the-beach-the-point-warwick-thornton-and-the-beach>, accessed 4 August 2020. – by hunting and foraging for food, a process he’s adept at, even though it sometimes frustrates him. Back at the shack, his catch will be transformed into a mouth-watering gourmet dish, prepared from scratch using some rustic cooking utensils and the aforementioned condiments. These simple, majestic meals are captured by cinematographer Dylan River (Thornton’s son and frequent collaborator) with a level of care equal to that of any cooking show.

It’s through our awareness of its contrivances and their inherent contradictions that The Beach derives much of its charm, humour and meaning. Thornton is alone in the company of others; his private solitude is also a public performance.

Somewhere in between these activities, Thornton will make time to sit on the front porch and share an intimate tale from his past – with his chickens. It’s a lighthearted device, but one with a serious purpose. Through these semi-prepared soliloquies, Thornton reveals glimpses of his struggles with depression, family and communal tragedies, and cycles of self-abusive behaviour, all of which may underlie why he’s out here in the first place. That these glimpses remain just that – glimpses, disguised in metaphors and oblique anecdotes – may in fact be one of the show’s less obviously ‘blokey’ aspects. What we see here isn’t quite a man being open about his emotions, but seemingly a man trying to learn how to be open about them.

Blokey though it may be, describing Thornton’s situation in The Beach as ‘survival’ would surely be overselling it. Those camera batteries had to be charged somewhere, and that bok choy cooked in Episode 5 had to stay fresh somehow. If this is survival, it is so only in the most prosaic sense of the word, encompassing the quotidian routine of working, cooking, eating and sleeping, to be repeated in more or less the same fashion each day.[4]In this respect, The Beach is far closer in spirit to the observation of a woodcutter’s daily routines in Lisandro Alonso’s La libertad (2001) or to Robert J Flaherty’s seminal ethnofictions than to the life-or-death survival narratives that frequent our screens. Thornton’s isolation is ultimately a choice and not a necessity: a scenario as essentially contrived as any fiction film, because he’s free to leave whenever he likes. Consequently, The Beach is a rather ‘clean’ affair; any genuine discomfort Thornton experienced during his stay has been minimised or omitted in favour of a more cohesive, and more romanticised, account. There’s no mention of the fact that he trod on a stonefish during the shoot and had to be taken to hospital,[5]See ‘Warwick Thornton and The Beach’, op. cit. nor is there any sign of the notorious sandflies of this region, and nor is there a single drop of rain shown, despite the series having been filmed at the tail end of wet season on the most cyclone-prone coast in Australia. Even a pre-meal slaughter of a chicken was staged, while another chicken – apparently taken by an eagle when Thornton is away from the shack – has also since been revealed to be safe and sound.[6]Siemienowicz, op. cit.

But it’s through our awareness of its contrivances and their inherent contradictions that The Beach derives much of its charm, humour and meaning. Thornton is alone in the company of others; his private solitude is also a public performance. His confessions to his chickens are also confessions delivered to the film crew gathered around him, designed to be relayed back to strangers watching at home on TV. He hunts and forages but is never going to starve, and the food he collects isn’t mere sustenance but forms the basis of meals of which any gourmet chef would be proud. And although Thornton is proficient at making do without the usual comforts, this doesn’t mean he always enjoys it. His fish nets sometimes yield nothing, his car gets bogged on the beach in one episode, and he complains habitually about the tools he has to deal with for the sake of maintaining the show’s thinly veiled illusion (he grumbles, ‘I hate these fucking things,’ as he tries to light an oil lantern; and ‘What the fuck is wrong with these scissors?’ as he makes a meal of a haircut). That this is all an act is precisely the point: Thornton is far less concerned about showing what his isolation might’ve actually been like than sharing what it meant for him, and him alone. This country isn’t something to be endured or survived, but to be cherished, experienced and represented in a way that only he can decide on. He isn’t being forced to do any of it, yet he’s forcing himself to do it all the same.

In its warping of mainstay TV genres and its playful blurring of documentary and fiction centring on a semi-famous figure from the film world, The Beach finds an unlikely companion in Fishing with John, the cult 1991 cable series wherein musician and actor John Lurie takes his celebrity mates on fishing trips around the world. Also comprising six episodes of around half an hour each, Fishing with John uses the fishing-show format to deliver a series of deadpan meanderings and absurd modernist flourishes, often presenting nonsensical accounts of fishing trips that bear little resemblance to what actually took place. But whereas Lurie’s seriesis a scrappy, lo-fi affair that only cobbled together its episodes in the editing room (and is hilariously upfront about the fact), The Beach is a meticulously crafted work on almost every level. It’s as precisely conceived, filmed, edited and sound designed as any of the fiction films for which Thornton is best known.

The show’s artistry hinges on its beach-shack setting, which is as memorable as any of the natural sights on show. Perched at the end of a sandbar among a nest of mangroves, it’s a lone, vulnerable marker of civilisation – particularly at high tide, when the ocean encroaches from all sides and strands the shack on its own island. Being an unmoving object, it also functions as a barometer against which the fluctuations of the surrounding nature can be gauged: nothing much seems to change out here, yet nothing ever remains the same. Within the world of The Beach, the shack’s origins are unexplained, and it thus retains an air of mystery from start to end. It appears to have been lived in before, but we aren’t told when or by whom; it has a history, but Thornton’s relationship to that history remains ambiguous. In reality, it’s an inspired work of set design: Thornton and production designer Herbert Pinter built it specifically for the show, with help from the local Lombadina Aboriginal community.[7]See Dilan Gunawardana, ‘The Healing Powers of Cooking and Country: Warwick Thornton on The Beach’, ACMI website, 27 May 2020, <https://www.acmi.net.au/ideas/read/healing-powers-cooking-country-warwick-thornton-the-beach/>; and Jo Litson, ‘Warwick Thornton: Beach Healing’, Limelight, 25 May 2020, <https://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/features/warwick-thornton-beach-healing/>, both accessed 4 August 2020.

The interior of the shack reveals a carefully designed film set that doubled as Thornton’s actual living quarters before and during the production.[8]The shack took two weeks to build, with Thornton spending around six or seven weeks living there in total. See Gunawardana, ibid.; and Siemienowicz, op. cit. Accordingly, its contents are both decorative and functional: there’s a mattress in the corner draped in a flowing white mosquito net, which becomes a meditative sight when Thornton lies down and contemplates; some benches for preparing meals, which are otherwise cluttered with an assortment of mysterious props; a small museum’s worth of old cooking tools (including a mortar and pestle, a brazier and a hand-cranked Mouli grater) that are summoned to utility at some point; and a large central table that hogs most of the floor space and houses Thornton’s condiments. Both fortuitously and by its very design, the shack filters the outside environment and allows us to experience it anew. Stretching across almost an entire wall is a large wooden panel that swings open to a panoramic view of the ocean; on another lies a series of smaller panels that can be adjusted to block or allow in natural light in increments – an ingenious feature that, in the absence of artificial lighting, allows Thornton and River to sculpt images with a great deal of precision. In one scene, Thornton sits and admires the stabs of sunlight piercing through gaps in the walls, crisscrossing the room like golden trip-wire. In another, a passing breeze causes his guitar resting by the doorway to reverberate with unearthly sounds; excited by this discovery and wanting in on the action, Thornton crouches on the floor and sways the door to and fro, modulating the sounds and nudging them towards music.

It’s difficult now not to draw parallels between Thornton’s isolation in The Beachand that of other ordinary people who have been forced to remain at home or otherwise distance themselves from their loved ones.

This shack is a place of reflection, creativity and refuge – and becomes an emblem of the intersection of documentary and fiction at which The Beach sits. It’s a fictional space, but one that’s used to stage a documentary; its design allows a level of aesthetic control and precision akin to a fiction film, but this was made possible also by a patient, unhurried documentary process. The Beach demonstrates Thornton’s intimate relationship with this space – its light, sounds, rhythms and quirks – and embeds it into the fabric of the work itself. Writing about Thornton’s culinary prowess, TV critic Jane Goodall suggests that ‘as he speaks of fighting off the black dog of depression, this display of virtuosity comes as an expression of the vital energy and intelligence also necessary for survival’.[9]Jane Goodall, ‘On the Beach’, Inside Story, 27 June 2020, <https://insidestory.org.au/on-the-beach/>, accessed 4 August 2020. It’s a statement that can be easily extrapolated to how The Beach was filmed. The degree of precision on display, the careful artistry and quiet virtuosity – also involving a lengthy process of labour, like Thornton’s cooking – are entirely fitting for a work about a man going to great lengths to regain control in his life.

One of the fascinating qualities of The Beach is how its themes and imagery seem at once culturally specific and universal, and appear to speak to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal experiences in equal measure. Any narrative about an Aboriginal man living in the city going bush will invariably carry connotations specific to Aboriginal people – the cultural and spiritual importance of (re)connecting with country, for one – and The Beach is no exception in this regard.[10]See, for example, Brooke Collins-Gearing, ‘Review: Warwick Thornton’s The Beach Is a Delicate Conversation with Country’, The Conversation, 27 May 2020, <https://theconversation.com/review-warwick-thorntons-the-beach-is-a-delicate-conversation-with-country-139464>, accessed 4 August 2020. But although Thornton has shot numerous films in this country over the years and knows it well, it’s also important to note that it isn’t his: he’s a Kaytej man, born and raised in Alice Springs and based in Sydney. This country, of the Bardi people, was chosen for its aesthetic beauty and its abundance of natural resources, but also for convenience – being relatively close to Broome, where Thornton was heading next to direct several episodes of the second season of Mystery Road.[11]Gunawardana, op. cit.

Knowledge of the fact that Thornton is a visitor in this country lends The Beach a more flexible, generalised appeal, transcending his Aboriginality without ever diminishing its significance. In interviews, Thornton has cited his immediate motivation for making The Beach – much more forthrightly than in the show, in fact, which merely alludes to it – as wanting to break the cycle of excessive drinking and partying that accompanied his life as a successful filmmaker.[12]The hints within the show include the unpleasant green concoction Thornton forces himself to drink on his first day, and his languid movements in the early episodes that suggest a man recovering from a prolonged hangover. When he later mumbles, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing,’ as he uses a knife to assemble some cocaine-like lines of palm sugar, it registers equally as a funny throwaway line and a confession about his life. While his connection to country remains no less important either way, this context nevertheless frames his isolation as much as a rehab or detox retreat as an act with deeper cultural and spiritual significance. Similarly, Thornton’s straightforward reverence for nature in The Beach espouses its nourishing effects for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people alike, while his skill in living off the land and off the grid celebrates traditional, Indigenous ways of life at the same time that it effortlessly latches on to broader global themes concerning environment and sustainability. Above all, there’s the food. Thornton’s meals rely on locally caught protein but aren’t anchored to any particular cuisine; they’re as diverse, and as multicultural, as the rest of the nation.

These multifaceted connotations have become even more so, owing to the timing of the show’s release. Although filmed almost a year earlier, The Beach premiered on NITV and SBS on 29 May 2020, in the midst of the (at the time of writing, ongoing) coronavirus pandemic that has divided the world both figuratively and literally. It’s difficult now not to draw parallels between Thornton’s isolation in The Beach and that of other ordinary people, in Australia and elsewhere, who have been forced to remain at home or otherwise distance themselves from their loved ones. Viewed in this light, The Beach can become an accidental metaphor for a shared, societal isolation, and perhaps also the feelings of boredom and loneliness – or, conversely, of reflection and even creative inspiration – that might come with it.[13]Reviewer Craig Mathieson writes that ‘Thornton has captured the emblematic tasks of the coronavirus’ stay-at-home era and made them into a statement of renewal’. Mathieson, ‘Warwick Thornton Delivers a Striking Confessional in The Beach’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/tv-and-radio/warwick-thornton-delivers-a-striking-confessional-in-the-beach-20200525-p54w3i.html>, accessed 4 August 2020. Depending on their personal circumstances within the pandemic, however, The Beach might remind viewers of the exact opposite of being in isolation. After all, Thornton’s isolation is a getaway and not a lockdown. The images of freedom and natural beauty depicted in the series may denote something unattainable, somewhere unreachable – an idyllic contrast to being in isolation, rather than a reflection of it.

Such is the baggage that must now be carried by a show about self-isolation, made before the word had any relevance to most of our lives. Far from being a distraction, however, its plenitude of meanings and textures only highlights its strengths. The Beach feels very much of its time, but it also feels as though it’ll somehow always remain that way. Its simplicity and restraint house a surprising depth of emotion, while its beautiful natural setting is one on which a vast variety of imaginaries can be projected, ranging from the personal to the social, the local to the global. Whether The Beach is appreciated as a character portrait, a poetic nature documentary or simply an offbeat cooking show, the fact that Thornton came away from the experience ‘clear-headed, healthier, absolutely fucking happier’[14]Siemienowicz, op. cit. is surely a bonus.

Endnotes

| 1 | Warwick Thornton, quoted in Rochelle Siemienowicz, ‘Warwick Thornton’s Big Time-out at The Beach’, screenhub, 26 May 2020, <https://www.screenhub.com.au/news-article/news/television/rochelle-siemienowicz/warwick-thorntons-big-time-out-at-the-beach-260427>, accessed 4 August 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | For the most part, Thornton was accompanied on location by cinematographer Dylan River, sound recordist Nicole Lazaroff and assistant camera operator William ‘Billy’ Wright. See Caris Bizzaca, ‘Warwick Thornton Turns the Camera on Himself’, Screen Australia website, 29 May 2020, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2020/05-29-warwick-thornton-turns-the-camera>, accessed 5 August 2020. |

| 3 | Warwick Thornton, in ‘Warwick Thornton and The Beach’, The Point, 29 May 2020, available at <https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/1738543683611/the-point-warwick-thornton-and-the-beach-the-point-warwick-thornton-and-the-beach>, accessed 4 August 2020. |

| 4 | In this respect, The Beach is far closer in spirit to the observation of a woodcutter’s daily routines in Lisandro Alonso’s La libertad (2001) or to Robert J Flaherty’s seminal ethnofictions than to the life-or-death survival narratives that frequent our screens. |

| 5 | See ‘Warwick Thornton and The Beach’, op. cit. |

| 6 | Siemienowicz, op. cit. |

| 7 | See Dilan Gunawardana, ‘The Healing Powers of Cooking and Country: Warwick Thornton on The Beach’, ACMI website, 27 May 2020, <https://www.acmi.net.au/ideas/read/healing-powers-cooking-country-warwick-thornton-the-beach/>; and Jo Litson, ‘Warwick Thornton: Beach Healing’, Limelight, 25 May 2020, <https://www.limelightmagazine.com.au/features/warwick-thornton-beach-healing/>, both accessed 4 August 2020. |

| 8 | The shack took two weeks to build, with Thornton spending around six or seven weeks living there in total. See Gunawardana, ibid.; and Siemienowicz, op. cit. |

| 9 | Jane Goodall, ‘On the Beach’, Inside Story, 27 June 2020, <https://insidestory.org.au/on-the-beach/>, accessed 4 August 2020. |

| 10 | See, for example, Brooke Collins-Gearing, ‘Review: Warwick Thornton’s The Beach Is a Delicate Conversation with Country’, The Conversation, 27 May 2020, <https://theconversation.com/review-warwick-thorntons-the-beach-is-a-delicate-conversation-with-country-139464>, accessed 4 August 2020. |

| 11 | Gunawardana, op. cit. |

| 12 | The hints within the show include the unpleasant green concoction Thornton forces himself to drink on his first day, and his languid movements in the early episodes that suggest a man recovering from a prolonged hangover. When he later mumbles, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing,’ as he uses a knife to assemble some cocaine-like lines of palm sugar, it registers equally as a funny throwaway line and a confession about his life. |

| 13 | Reviewer Craig Mathieson writes that ‘Thornton has captured the emblematic tasks of the coronavirus’ stay-at-home era and made them into a statement of renewal’. Mathieson, ‘Warwick Thornton Delivers a Striking Confessional in The Beach’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 2020, <https://www.smh.com.au/culture/tv-and-radio/warwick-thornton-delivers-a-striking-confessional-in-the-beach-20200525-p54w3i.html>, accessed 4 August 2020. |

| 14 | Siemienowicz, op. cit. |