I am often asked to speak about ‘traditional’ distribution. Or sometimes it’s ‘heritage’ or ‘legacy’ distribution. But, whatever the terminology, the attitude implies that the arena I inhabit is old-fashioned, quaint and a mere adjunct to what is now really important: the exploitation of the ‘new’ (i.e. digital) platforms and social media. I usually argue that I work in distribution – without a preceding adjective – and that we all need to pay heed to the same things, whether we work with cinemas and DVDs or digital platforms. We all need to find the most effective language (verbal and pictorial) for communicating with audiences and building the widest possible public awareness of our work.

These days, I work with digital platforms as well as with the modalities that I have always worked with over more than forty years in the trade. My experiences, accumulated as an independent entrepreneur during those decades of trial and error, are relevant today, and it is not hard to extrapolate lessons from these experiences that can enhance an understanding of the new media landscape.

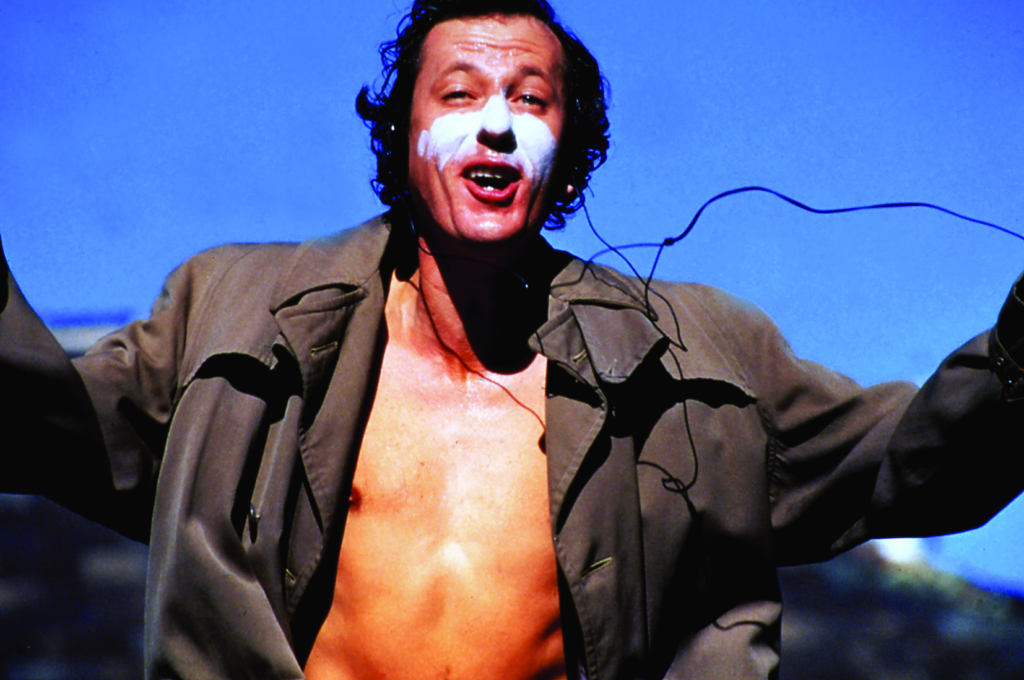

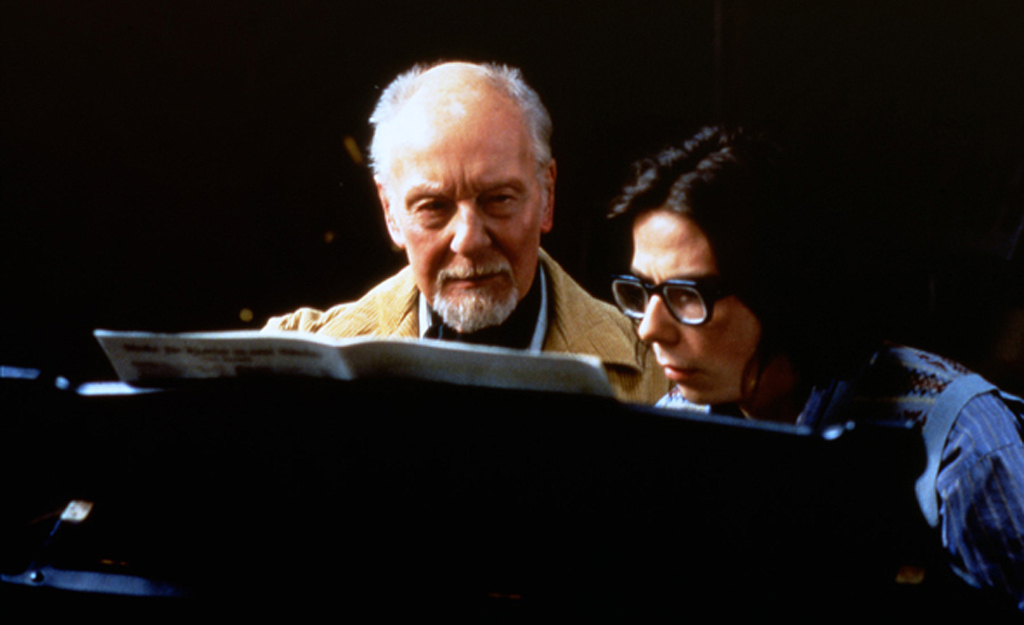

For me, the most exciting release that my company, Ronin Films, managed was Shine (Scott Hicks, 1996), about pianist David Helfgott (played in the film by Geoffrey Rush and Noah Taylor). It wasn’t our biggest success, but it traded very profitably indeed and surpassed many expectations for a drama about mental health and classical music, at a time when the most successful Australian films were flamboyant comedies. It was also the campaign in which a lot of our marketing ideas were applied for the first time in a systematic way. I believe that the ideas and principles behind its release are valid to this very day, although technical delivery may differ. It has always intrigued me that no government agency has ever asked for a debrief about the Shine campaign (or, for that matter, any of our other campaigns), and no academic has expressed interest, even though there are now a number of academics interested in marketing and distribution history. So I have decided to tell the story myself, now that we have just celebrated the twentieth anniversary of the film’s release.

I often feel that the local film community and academic observers are overly preoccupied with the dire Australian share of the national box-office gross. We have endless studies of what is wrong, and endless scriptwriting workshops to try to fix the problems perceived in production. We get very little – or no – analysis of the occasions when something different happened, when certain Australian films took an unusually large share of the box office. The good years tend to be dismissed as ‘blips’ on the scale, and the films, dismissed as ‘freaks’. No-one has thought to ask what we did to gross A$10.5 million with Shine or A$21.5 million with Strictly Ballroom (Baz Luhrmann, 1992).

As the producer of Shine, Jane Scott, once said to me, no-one asks about the film’s campaign because they don’t realise that there actually was a campaign. People seem to think it all just happened: ring a couple of cinemas, stick a few ads in the papers, book a couple of TV spots, do a couple of media interviews, and the public comes or it doesn’t. I can understand why my old mentor, Ken G Hall, became so embittered and went to his grave despairing that no-one ever asked him how he directed sixteen features in a row in the 1930s that, all but one, were commercial successes. But Shine, in fact, had a deliberate and calculated campaign – or, rather, a series of campaigns. In 1992, we released Strictly Ballroom, which performed very well at the box office; it had a huge and exciting campaign, but our strategies evolved organically in a piecemeal fashion as the film’s release ballooned out. But four years later, with Shine, it was different: we had a campaign that was closely managed in every aspect – and it worked. The American distributors, Fine Line, sensed something interesting was going on and sent out two observers who monitored the whole campaign for several weeks, searching for ideas to apply to their own campaign back in the US. To my knowledge, this close observation has rarely happened, before or since, with an American distributor choosing to monitor an Australian campaign at a grassroots level, day by day. What they learnt and took back, I never found out, but it was significant that they thought it was all worth watching.

Shine, of course, was a very good film, and its quality was a crucial factor in its success. But there have been many great films that have failed to find an audience. My aim in this essay is to look at the process by which we gave the film the optimum chance to find its audience and to succeed at the box office.

Phases in the campaign

Our campaign for Shine was planned as a series of overlapping and interlocked phases.

I like to think of the preparatory stage of the campaign – the assembling of our team – as a little like the process of gathering the warriors together in Seven Samurai (Akira Kurosawa, 1954). Since we did not have an in-house publicist at this time, I needed to find a freelance publicist to design and orchestrate the national campaign with me. My first preference was Tracey Mair, a publicist with whom we had had occasional contact and who always exuded authority and confidence in her work. Having her on our team meant that I could discuss the full campaign strategy with her and then leave her to devise and deliver it while I concentrated on other areas. In essence, we agreed that she would manage the media, the actors, the filmmakers and the Helfgott family, while Ronin concentrated on business aspects of the release, especially managing our relationships with cinemas. Ronin would also take charge of all paid advertising. We arranged for Mair to see the film, and she had no hesitation in coming on board, even though she was pregnant and warned that she would have to give priority to her health and to the baby. We managed to get the film released before she gave birth and, although she later claimed that she was working ‘in a fog’ through the latter stages of the release, we did not notice any difference in her manner or her effectiveness.

With our team leader in place, we then needed to build the rest of the crew. Mair needed support staff in the major capital cities: she intended to handle the national publicity and most of the Sydney publicity, but we wanted other contract publicists to work under her supervision in Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth. At that stage, Ronin no longer had a Sydney office – we were based in Canberra, and we managed the local Canberra publicity.

I’d worked for years as an independent exhibitor and had been on the receiving end of distributors, large and small. But I was never asked what my thoughts were about a campaign … I didn’t want that sort of relationship with the exhibitors with whom we would be working on Shine.

But I wanted to do more than simply put a network of publicists in place; I wanted to pursue a more ‘holistic’ approach. Going back to Strictly Ballroom and other releases we had done, I’d always been very impressed by the ingenuity and aggressiveness of the promotional ideas that emerged from the home-video market. I wanted that sort of inventiveness injected into the theatrical release, not just tagged onto the end when the film went to video. To this end, I recruited Ray Robinson, an expert in the home-video business, to join our team and to help me eventually secure the best possible deal.

I was also insistent that we involve exhibitors in designing promotional materials and activities. Very often, distributors talk about exhibitors as though they are some sort of enemy that needs to be whipped into shape and then gouged for every last dollar. I’d worked for years as an independent exhibitor and had been on the receiving end of distributors, large and small. But I was never asked what my thoughts were about a campaign, or what I thought best suited a particular film in terms of sessions. I didn’t want that sort of relationship with the exhibitors with whom we would be working on Shine. After all, they were our shopfront: they would be selling the tickets, and we needed their goodwill and cooperation and, even more than that, we wanted them to be enthusiastic.

Phase #1: Within the film trade itself

With our team secured, the first layer of the broad campaign could begin: winning the hearts and minds of the exhibitors. Because we would be going out initially on an estimated fifty screens, we would be dealing with myriad independent exhibitors as well as the major cinema chains.

With Strictly Ballroom, we had had an extremely difficult and frustrating time getting exhibitors to agree to show the film: everyone (except us!) was nervous and reluctant to commit to the film until our campaign material and – most importantly – our advertising dollars were on the table. But, with Shine, it was a totally different experience: everyone loved it and saw that it could make money, and they all wanted to book it. Even before we had set a date, we had most of our exhibitors – majors and indies – in place. But I didn’t just want the bookings; I wanted much more from the cinemas – their deep commitment to this film, a commitment to work hard to protect and nurture it in their cinemas, not just in the first fortnight, but in the long term.

Achieving this commitment was the aim of the first stage of the campaign.

We decided to hold a two-day residential workshop in Sydney to discuss every aspect of the release. We stretched our budget to cover the accommodation and travel costs of bringing exhibitors and home-video people together in one room to examine our draft campaign materials and to discuss advertising strategies. We held the workshop at Ravesis on Bondi Beach in Sydney, and accommodated maybe twenty people during the exercise. Mair’s publicists were there, as were producer Jane Scott, Ray Robinson, and representatives of the major exhibitors and key independents. Others came for just short visits, among them director Hicks, some of the film’s investors, and Helfgott himself, accompanied by wife Gillian. Helfgott was at his most charming and helped greatly to make the atmosphere friendly and informal. I especially wanted our team of publicists to feel that they were working on something special, not just a routine ‘gig’, and for them to feel united as a team, to understand our aspirations and strategies.

During those two days, we looked at various poster designs as well as a rough cut of the trailer that we had commissioned from a brilliant trailer editor, Stephen Robinson, and we discussed how best to arrange a tour of cast and crew members to cinemas for personal appearances. The atmosphere was very positive and excited. We were genuinely looking for feedback to help shape the campaign, but we were also conscious of the need to ‘buy’ the commitment of the exhibitors and secure the confidence of the investors, the filmmakers and the Helfgott family. At the very least, I am confident we secured an awareness that this was no routine release – that it was special, and that we were going to make it special. If the exhibitors wanted to book this film, they had to really want to show it.

As far as I’m aware, such workshops are unusual. Brainstorming sessions and group activities may happen within companies, but to hold one across all media involved in a film’s release (theatrical and home video combined), and across all participants, was unusual. I’ve never heard of a similar exercise: certainly, in my twenty-seven years as an exhibitor, I was never invited to one or ever heard of one happening. In a way, it was our own ignorance of ‘normal’ industry procedure that led us to hold the workshop.

The classification

One of the reasons we initially signed up for Shine was because I felt it had excellent potential for secondary school audiences, an important ancillary market for us.

We had long specialised in selling videos to schools in the education market, and knew it to be a strong and steady market that could respond positively to Shine. ‘Personal development’ was one of the major subjects in national curricula at the time, and Shine was essentially a case study in a fairly unusual form of personal development. We knew that, to be effective in the education market, we needed the film to have a PG classification. We routinely submitted the film to the censors for classification and were alarmed when it came back with an M classification for ‘Mature’ audiences. While this rating didn’t preclude anyone from seeing the film, it carried an implied warning that the film was not suitable for audiences under the age of fifteen. I was not at all pleased; not only did I worry that this would definitely inhibit the film’s chances with the school audience, but I was also concerned that it might give the wrong message to older matinee audiences, who don’t like violence or excess of any kind, and who want a quiet, uplifting experience (which we knew the film would give them).

Geoffrey Rush was known mainly in the specialised field of Australian theatre … our solution was to capitalise on the actor’s relative lack of public profile by introducing him to the media – and, by extension, the world – as a ‘new star in the making’.

Accordingly, we lodged an appeal against the classification. Under the film-classification arrangements at that time, censorship was a state matter but was delegated to a federal body to make classification uniform across the country. The result of our appeal on Shine was extraordinary and, as far as I am aware, unprecedented. After our appeal was heard, we were granted a PG classification in all states except one, Western Australia; there, Shine was still rated M. The reason for this split was that there was a Western Australian representative on the appeals board who was concerned about the film’s depiction of child abuse – she was wary that the portrayal of the father’s emotional violence and abusive behaviour towards the young David would be distressing for young audiences.

Formally, we had no further rights of appeal and were officially burdened with an unworkable situation. We would have to carry two classifications in all our advertising – something that would be unwieldy for us and confusing for audiences, to say the least. We sought legal advice and lobbied with politicians, and eventually presented our case in a lengthy direct appeal to the Western Australian premier himself. After quite some time, the premier decided to intervene in the interests of logic and practicality, and overruled his appeals board representative; the film then achieved a PG classification nationally.

I still cannot understand how the Classification Board, dealing with professional film organisations every day of the week, could – in all seriousness – come up with a split decision that they must have known was completely impracticable, yet expected us to work with the result.

Phase #2: An unknown star

One of the challenges facing us was the fact that we did not have a known star. We had some moderately familiar names among the supporting players (Googie Withers, Lynn Redgrave, Noah Taylor, John Gielgud, Armin Mueller-Stahl), but Geoffrey Rush was known mainly in the specialised field of Australian theatre. There, he was an important figure, but he had done very little film work and was not known by the general cinema-going public. We faced a similar problem when we launched Strictly Ballroom: we had a star, Paul Mercurio, who was known in the world of dance, but who was virtually unknown beyond that field.

In both cases, our solution was to capitalise on the actor’s relative lack of public profile by introducing him to the media – and, by extension, the world – as a ‘new star in the making’. Quite separately from publicising Shine or Strictly Ballroom directly, we prepared special press kits about the two actors, which covered their whole, very distinguished, careers up to that point, and ran a media campaign focused on them. With Mercurio, we cut a special video clip that introduced him, and we printed portrait posters of him, persuading our cinemas to display the posters and run the video on their monitors. The aim was to create anticipation surrounding this exciting ‘new’ star.

Whether we succeeded or not in creating a public profile for Rush or Mercurio, at no time did we ever feel that it was a disadvantage having an ‘unknown’ star, and we never complained. On the contrary, I think we felt that it was an advantage that gave us an excuse for a dedicated publicity push within our overall campaign. I remembered how Hall dealt with the lack of known stars in Australia in the 1930s and set about creating new ones: his ‘creation’ of Shirley Ann Richards, in particular, was a model for our thinking with Mercurio and Rush.

The launch

After initiating our plan to win the hearts and minds of the film trade, we began to shape our campaign to convince the media to support the film.

Premieres and attendant social functions can become a nightmare for publicists, and can be a time-consuming distraction from the work of building public awareness about a film. A red-carpet premiere is often more important for the production team than for anyone else, and can soak up an enormous amount of energy, time and money that might be better spent on promotional activities that have more widespread national outcomes.

Even though we were well aware of the risks of big premiere functions, Mair and I both decided on having a red-carpet event to give the film the appearance of the significance that we thought it ought to have. At the same time, we wanted to devise a premiere that would be effective on a national level, not just for the immediate participants. Essentially, we saw a premiere as a starting point for media coverage, not an end in itself – not distracting us from our principal work or draining our resources, but rather setting the tone for the whole national campaign.

We decided to hold the launch in Adelaide, away from the usual venues for such events in Sydney or Melbourne. The film had been selected for the Sydney and Melbourne film festivals, and we had guest appearances there with cast and crew, but we deliberately played down these events, reserving the main event for the South Australian capital. Adelaide was not without logic – a lot of finance for the film had come from the South Australian Film Corporation, Hicks hails from Adelaide, and some of the film had been shot there (even though the story was set in Perth). We also had a suitable venue there: the local Academy Cinema was very keen to exhibit the film, and the programmer, a courteous, gracious gentleman named Bob Parr, and his extremely efficient cinema manager, Paul Besanko, were keen to collaborate with us.

To turn the premiere into an event that would make a real media splash, we decided to stage it on a Friday night and turn the next day into a total immersion experience for media from all over Australia. We invited key media players from every state to attend (about forty in all), provided them with airfares and accommodation, and planned an intensive day of post-premiere activities for them. After the red-carpet premiere, complete with searchlights and brass band, we held a large party at the Adelaide Town Hall. The next morning, we shepherded everyone onto a specially chartered train to go to the Barossa Valley, where we had booked a gourmet lunch for everyone at a winery-restaurant; Helfgott was promised as a special guest at the lunch. Almost everyone went by the private train, including Rush and other cast and crew members, but Hicks and David and Gillian Helfgott drove from Adelaide in a limousine, to make a grand entrance after everyone else had arrived at the winery. The train itself was special, as the line had been closed and trains no longer ran out to the Barossa – we had to make a special booking, which the state rail authority was happy to do for a modest price. After the lunch and the concert, we offered our guests the chance to attend a ball with a movie theme; this event was an annual charity hosted by the lord mayor of Adelaide, and we were fortunate to be able to include it in our special media weekend. On Sunday, we flew all of the media back home.

The goodwill created by the launch weekend served Ronin well for many years to come, and gave me lasting friendships with many members of the media and film critics whom I hadn’t met before. But, quite apart from goodwill, we achieved a huge amount of press coverage nationally: the fundamental aim of the exercise.

Clearly, the Adelaide launch and the media weekend cost a fortune, and we had not anticipated this cost when we prepared our marketing budget. Mair and I visited Adelaide a few months in advance to seek sponsorship and managed to find two generous supporters, in addition to the Academy Cinema itself: the Adelaide branch of the Deutsche Bank came on board with a cash sponsorship, and a local winery joined us by providing champagne for the launch – not only for the national premiere in Adelaide, but also for smaller premiere functions in other capital cities. These sponsorships didn’t come anywhere near covering all of our expenses, which required us to restructure our budget as we plunged into the most intensive work of the release.

Phase #3: The media campaign

As Mair’s team organised and managed media interviews, public appearances, press conferences and press releases in the weeks leading up to Shine’s release, we made it a conscious part of the campaign to involve as many of our exhibitors as possible. Everyone screening the film was kept informed of the publicity plans, ensuring that they felt part of something important and encouraging them to contribute their own ideas in their own locations.

We wanted the exhibitors to feel involved – to get the sense that we cared about what they were doing, and that we didn’t see the booking as the end of the communication … Our job as distributor was to maximise every possibility that the cinemas offered us.

Because Shine is based on the lives of real people, we felt that media exposure of these real people needed to be managed carefully to avoid any chance of the film being seen as a dramatised documentary, and especially to make sure that Rush’s performance was never regarded as ‘mimicking’ Helfgott’s distinctive personality.

Mair and I decided that we would limit media access to David and Gillian Helfgott to four interviews – two radio and two print. Apart from these, media access was not permitted, and the Helfgotts agreed to direct anyone who approached them to Mair. The strategy worked: we secured massive media coverage but never lost sight of Shine as a distinguished movie. Members of the media were never given a chance to compare and contrast the real characters with their screen counterparts.

Phase #4: Relationships with the cinemas

As we had done for Strictly Ballroom, we did our best to get exhibitors and their staff to see the film and meet the filmmakers. With the Hoyts chain, for example, we held a special preview at its head office for its various location managers, and brought the filmmakers in to meet them. Our publicists also went, wherever possible, to the cinemas in the field to meet with local cinema staff and to talk about the film, helping them generate ideas for displays, leafleting and personal appearances of cast members wherever that could be arranged. My own staff in Canberra, responsible for booking the film into cinemas, backed up the publicists by frequently ringing or faxing cinemas whenever there was an excuse for an update. Several exhibitors in suburban and regional locations told us how much they appreciated the personal attention and said that ‘no-one ever did that’ in the film trade. Quite a few exhibitors responded to the attention by taking initiatives to develop local promotional tie-ins, pursuing local group bookings and making special displays in their own cinemas as well as in other commercial or community facilities.

We wanted the exhibitors to feel involved – to get the sense that we cared about what they were doing, and that we didn’t see the booking as the end of the communication. Once Shine had opened, we were also as flexible as we could be with sessions, and made a point of talking to exhibitors to show that we had an ongoing interest in what they were doing with the film and how each session was going. As reviews appeared, we circulated enlargements for displays and sent them out for cinema display boards. We also kept refreshing advertising designs and disseminating them. Our job as distributor was to maximise every possibility that the cinemas offered us.

Free previews

One of the scariest things we learned during the Strictly Ballroom campaign was that, if your film is good, there is no harm in previewing it relentlessly for free, in return for promotional opportunities. With Shine, we ran countless free previews in association with promotions on radio programs, in magazines or newspapers, and with special-interest groups in the community. Special previews for hairdressers were organised, for example, on the assumption that a hairdresser who loves a film will talk about it with customers. Likewise, taxi drivers were invited to previews.

We ran so many free previews, in fact, that cinemas and even the producers began to worry that we were using up the audience and that there’d be no-one left to buy tickets. In the end, we were convinced that the number of free previews didn’t matter, provided that the outcomes of free promotion were achieved in return. I have no doubt that the positive word-of-mouth from these previews helped to kickstart Shine’s positive performance at the box office.

The date

One of the most crucial decisions facing any release is the choice of opening date.

We were very fortunate that, for Shine, we were able to identify a date that gave our film a distinct advantage. It had always been our intention to launch in mid August – not too long after the Sydney and Melbourne film festivals, so that we could maximise the word-of-mouth from the screenings there, but also not too close to the September school holidays so that we had a chance of a few decent weeks before the plethora of holiday films might force us off local screens.

The release of Independence Day (Roland Emmerich, 1996) was a gift for us: it had enjoyed a huge amount of advance publicity, and was predicted to swamp all competition to become one of the top box-office hits of the decade. With a little advance research, we discovered that no major distributor was planning to release any new film against Independence Day – it was as though the tide was receding prior to a tsunami. But we realised that this sci-fi blockbuster was going to appeal to exactly the opposite audience that we wanted to attract for Shine: they wanted teenagers above all, whereas we wanted adults.

Accordingly, we positioned ourselves to open two weeks in advance of Independence Day, against almost no competition from major distributors, and we argued our case on the basis of ‘counter-programming’: by running Shine, exhibitors could bring a different audience into their cinema complexes and keep faith with their older clientele.

Most exhibitors happily agreed with us and booked us in for four or five weeks with few qualms (or, at least, not any that they expressed to us). Even if Shine opened slowly, we knew we were relatively safe because there was nothing else that was available during that period to displace us, other than Independence Day. So Shine and Independence Day sat side by side for several weeks as stablemates, and our performance was respectable enough to keep us on minor sessions during the school holidays that followed.

In-season success

Once it had established itself in cinemas (thanks to Independence Day), Shine had a continuous run of luck that kept it alive in the media and on our screens. First were the AFI Awards and the media coverage that we were able to attach to Shine’s success as a multi-award-winner. Then, Shine started to make headlines overseas: it won a Golden Globe and the New York Film Critics Circle Award, both for Rush’s performance, and began being talked about as a favourite for the Oscars. Again, all of this provided excuses for more media releases and more nurturing of our relationship with cinemas. In fact, it was no trouble to keep the fires burning, building on our goodwill in the trade.

But one of our luckiest breaks came from Barbra Streisand. Despite the success of Shine with awards both locally and in the US, our prospects over the Christmas holidays looked grim. We’d been lucky to hang on in cinemas since August, but local cinemas generally start booking new titles for the Christmas holidays from mid December onwards and we were being squeezed out. One of the new Christmas releases through mainstream cinemas was Streisand’s The Mirror Has Two Faces (1996). It had a big campaign and got major exposure in cinema schedules. However, once it opened, it was quickly apparent that it wasn’t drawing the expected crowd. Exhibitors looked around for a replacement film and many of them chose to reinstate Shine, an opportunity that we quickly maximised by introducing new press-ad designs and new TV commercials, to make the film look as fresh to the holiday crowd as possible.

The strategy based on the failure of the Streisand movie saw us through the summer school holidays. After that, February was easy: the Oscar nominations came out and everyone jostled for the film. By this stage, we weren’t precious about sessions or commitments; we just wanted screens – and got them. Again, was it goodwill? I think what we had already nurtured had a lot to do with it: we never let up on communication with exhibitors, including those that had dropped the film. From a starting point of some fifty prints of the film on fifty screens, we rose to a peak of 120 prints; my staff were constantly juggling them to keep up with the demand in regional areas as well as the cities. Many of the seventy extra prints were struck well into the release because cinemas were hanging onto their prints and we couldn’t meet other commitments.

We also conscientiously backed up any and every cinema booking with advertising in the press, both local and national, on radio and on TV; where appropriate, we also organised personal appearances, press releases and interviews. We kept all of our publicists on call, and Mair remained in charge throughout. Our advertising bill blew out to huge proportions: combined with the cost of prints and trailers, the prints and advertising (P&A) budget came close to A$1.8 million. But our gross box-office figures also escalated steadily and reached A$10.5 million before it all slowed to a halt a couple of months after the Oscars, where Rush won Best Actor. Overall, we survived in cinemas nationwide for eight months.

On financial terms, one of the significant pay-offs was that, by having passed the A$10 million mark, we received more money from television, as we had secured a sale that was tiered according to gross box-office results. So the extra money from TV more than made up for the excess in P&A costs.

Phase #5: Press advertising

The media campaign and the personal appearances created public awareness nationally and a widespread interest in seeing the film. But there was another campaign phase – one, in my view, that is often ignored or undervalued.

Our task was to convert that general awareness into action – the action of buying of a ticket. The key to this conversion was, in my belief, the press advertisement. Nowadays, digital platforms and social media may provide a similar function, especially for younger audiences; for many, however, it’s still the press ad. It is in the press ad that the public can see when and where the film is showing, and the ad encourages them to act, to make decisions.

Today, even when one is using non-print media to carry advertising messages, I believe that, whenever press ads are used, they still require careful consideration and management.

Our aim was to make every press ad a winner. The whole notion of ‘key art’ that is prevalent in distribution and exhibition these days is a problem we set out to avoid. The ‘official’ key art provided by distributors can limit a campaign to one style of ad with one style of text. We didn’t want just one piece of key art for Shine – we wanted several. We selected our key art for press ads in the opening two weeks, but before we even opened the film, we had very different key art in place for ads in Weeks 3 and 4. The differences were designed to attract curious members of the public who may have heard of the film but needed to be convinced to go and buy a ticket. As long as the film continued to run, we continued to devise new designs for the press ads.

Working with me on the press ads was Sue Faulkner; essentially, she ran the ad campaign on her own, from our office in Canberra, designing each new wave of the ads herself and sending them out to cinemas for months on end. Part of the ‘freshness’ lay in our responsiveness to local conditions. I’d learnt from experience running our cinemas in Canberra that local quotes by local Canberra critics always prompted more ticket sales than ads that quoted critics from ‘outside’. We constantly gave exhibitors the opportunity to freshen their own ads by sending them ‘quote banks’ and by incorporating quotes from reviewers in their own locality in their ads. All of this took a huge amount of highly detailed work on Faulkner’s part, but my belief is that it paid off.

We also aimed, wherever possible, to name cinemas and even session times in every ad we ran. The idea of using a generic advertising tagline like ‘In Cinemas Now’ was unthinkable to us; it seemed like the height of non-communication. We believed that our press ads had an important job in triggering the action of buying tickets: not only did we want to maximise the impact of our campaign by constantly refreshing the artwork, but we wanted to maximise its effectiveness by giving all of the information anyone could possibly need in order to buy a ticket.

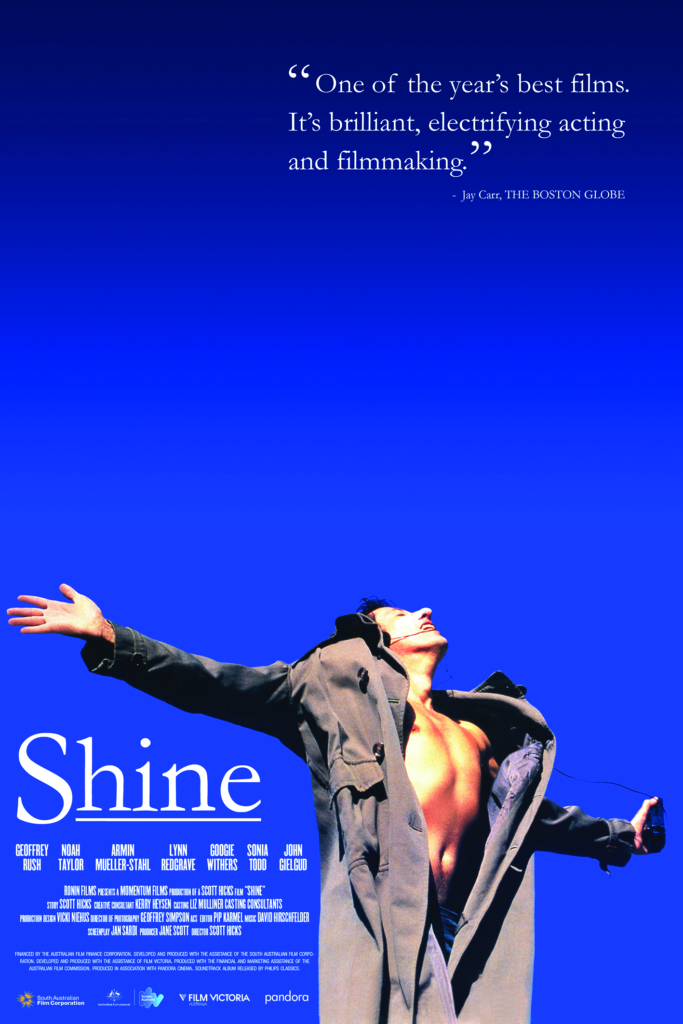

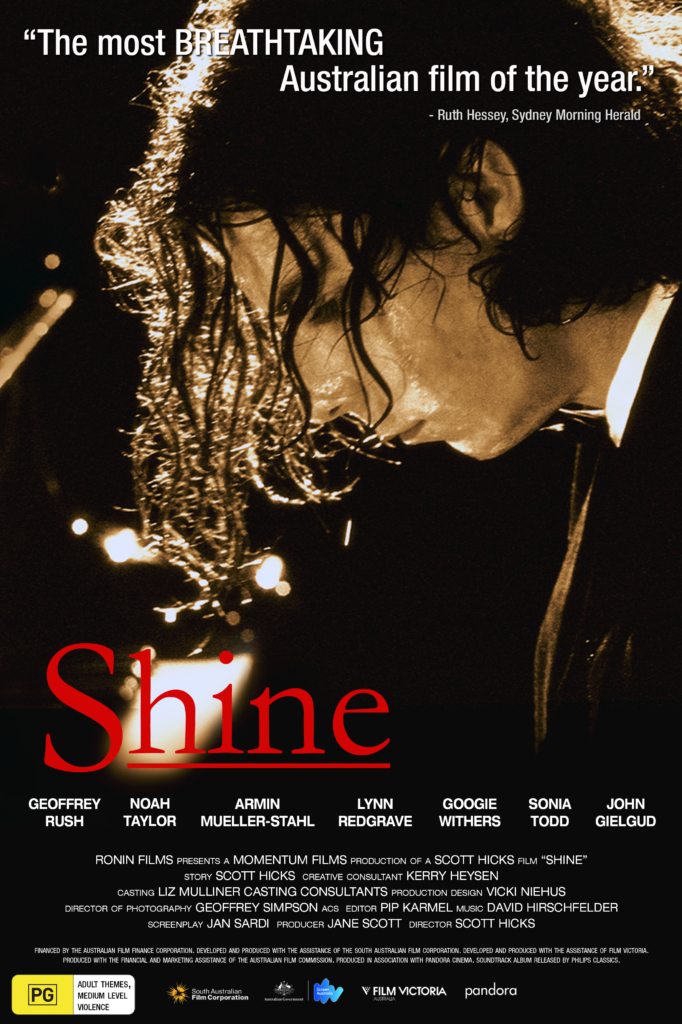

The poster

Producers often agonise over posters but ignore press ads. With Strictly Ballroom, we spent enough money on poster designs to fund another film! On that film, the design that we wanted was rejected by the producers, and they spent ages – and a lot of their own money – searching for something that satisfied them. Once the poster was locked off, we then braced ourselves for their involvement in the design of the ads, but they showed no interest; it was clearly up to us. So we gallantly proceeded to use our own original (and rejected) poster design as the key image for our press ads, and ignored their poster design in our ads.

Personally, I rank the design of the press ad as being far more important than the design of the poster. Too often, producers design posters that will look good on their walls at home or in their offices; they assume that the same poster will work in the cinemas. My belief is that there is a significant difference between a poster as fine art on a wall at home, and the poster that is effective in a cinema foyer. The poster in the cinema will be glanced at quickly as a patron passes by, and it needs to convey a single clear message that stands out from all of the other posters surrounding it. It’s not the place for subtlety or sophistication. Posters in the cinema lobby are also often seen after the decision has been made to buy a ticket, or when the patron is there to see something else, and have little immediate impact on the decision to buy a ticket.

For this reason, I’ve rarely fought with producers over what they wanted for a poster design. If they don’t want to follow our advice, then it doesn’t really matter too much. On the other hand, I will fight tooth and nail to get the press ads I want, because I believe that their design is critical to a film’s chances – both the images used and the text that accompanies them.

With Shine, the producers did heed our advice and we had no disagreements about the artwork at any stage – for poster or for ads. We all agreed on a single strong image for the poster, and it had a striking impact wherever else we used that image, whether in leaflets, press ads or invitation cards.

The gamble

Hall repeatedly told me that everything in the film business was a gamble, and that our job as distributors and exhibitors was to recognise that fact and do everything we could to minimise that gamble. I took his simple message to heart and would often quote his philosophy of minimising risk. It’s hard to remove risk altogether because there are so many variables. You can do a great campaign with great ads, and then get shot down by a bad review in the local paper. Or everything might be going for you, then a savage electrical storm can sabotage your opening night (which happened to me on more than one occasion).

But, if you are aware of the gamble and plan around it, you can improve your chances. This notion was very much at the forefront of the Shine release, from the planning workshop through to the last little country cinema that booked the film.

Ronin’s inexperience

With all of our work, whether it was busily communicating with exhibitors or constantly refreshing our ads, I still have no idea if other distributors did these things, or even do them now. I suspect they don’t, beyond the immediate first-release venues. I am not sure whether we were making a difference or whether we were just making work for ourselves. I like to think that we did make a difference – that our efforts did translate into something meaningful within the trade and for the general public. But precisely what that difference was, I am not sure. But I’d do it again that way if I ever went into another major release.

Certainly, in my experience as a small exhibitor in Canberra, I rarely received goodwill calls or encouragement from distributors. Troy Lum from Hopscotch was one of the few who regularly rang to check how I felt about his latest release and to ask for feedback on his company’s ad campaign. I usually had Lum’s permission to change his ads to suit the Canberra market. Often, with other distributors, I’d just change the key art anyway to suit my locality; no-one ever complained or seemed to take any interest in what a regional cinema did, if indeed they were ever aware.

Ultimately, the way we went about distribution ourselves was based very much on what I wished for myself as an exhibitor. Too often, as a regional exhibitor in Canberra, I was given the dregs of a campaign to work with – a few scraps of leftover publicity material, rarely a filmmaker as a guest, and hardly ever a call from a publicist. We were an afterthought that got in the way of their work on their next big release.

I feel proud of the Shine campaign for many reasons: it worked, and it worked well, and no-one was damaged by it. It built morale for my team, and set Mair on a significant career. And still today, twenty years later, I feel echoes of the goodwill we created when I talk with exhibitors from that period. And significantly, because of ongoing goodwill between us and the production team, I feel proud that, through the campaign, we were able to contribute in some small way to an enhancement of the careers of the cast and filmmakers. Of course, the quality of their work on the film itself proved their abilities for all the world to see, and would have done so without us – but I like to think that we helped.

http://www.roninfilms.com.au/feature/13543/shine.html

https://clickv.ie/w/metro/shine