Each and every one of you is considered an equal within the walls of this facility. You must be guaranteed the same opportunities without being disadvantaged or facing any kind of discrimination.

– The Frontman (Tom Choi), in Episode 6 of Squid Game

The battle royal is an increasingly prevalent narrative trope. Originating in combat sports,[1]See John S Nash, ‘Wrestling with the Past: The Bizarre Origins of the Battle Royal – Part One’, Cageside Seats, 9 March 2013, <https://www.cagesideseats.com/2013/3/9/4028970/battle-royal-WWE-Boxing-wrestling-with-past-origins-history-combat-sports-part-one>, accessed 24 November 2021 free-for-all elimination tournaments have since been codified into their own form of mass entertainment. Instances of no-holds-barred ‘death matches’ readily abound in popular culture: the ‘last person standing’ narrative arc has been prominent in novels,[2]See, for example, Stephen King’s The Long Walk and The Running Man and Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. films,[3]See, for example, The Most Dangerous Game (Irving Pichel & Ernest B Schoedsack, 1932), The Running Man (Paul Michael Glaser, 1987), Hard Target (John Woo, 1993), The Hunger Games (Gary Ross, 2012), As the Gods Will (Takashi Miike, 2014) and The Hunt (Craig Zobel, 2020). television shows[4]This is particularly prevalent in Japanese anime series: see, for example, Gantz, Kaiji: Ultimate Survivor, Liar Game, Fate/Zero and Death Parade. Other recent television shows that deal with this theme are 3% and Alice in Borderland. and videogames.[5]See, for example, PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, Fortnite, Call of Duty: Warzone and Apex Legends. Although Battle Royale (Kinji Fukasaku, 2000) is widely regarded as the originator of the concept of literal elimination rounds, the film adaptation of the Kōshun Takami novel of the same name[6]Koushun Takami, Battle Royale, trans. Yuji Oniki, VIZ, San Francisco, 2003 [1999]. merely resurrected an ancient blood sport: Roman gladiator games, which primarily involved captured slaves.[7]Kathleen Coleman, ‘Spectacle’, in Alessandro Barchiesi & Walter Scheidel (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2010, pp. 651–71. It is no coincidence, then, that battles royal figure prominently in historical slavery narratives[8]See Sergio Lussana, ‘To See Who Was Best on the Plantation: Enslaved Fighting Contests and Masculinity in the Antebellum Plantation South’, The Journal of Southern History, vol. 76, no. 4, p. 917. The website of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia also provides extensive examples of advertisements for battles royal and excerpts from slave interviews; see Franklin Hughes, ‘Negro Battle Royal – May 2014’, Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia website, May 2014, <https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2014/may.htm>, accessed 24 November 2021. or recur in stories about descendants of slaves learning to live with their heads in lions’ mouths.[9]‘Battle Royal’ is the title of the first chapter of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, which describes the unnamed Black protagonist’s experience of fighting other blindfolded African-American men for the entertainment of rich white audiences. ‘Live with your head in the lion’s mouth’ is the deathbed advice given to him by his grandfather, a former slave. Ellison, Invisible Man, New York, Vintage Books, 1989, p. 16.

The resurgence of gladiatorial contests – as either a relatively passive viewing experience or through active participation – is obviously not without cultural significance or historical import. The popularity of battles royal distils a contemporary worldview – namely, that the social contract is really a zero-sum game. Instead of viewing social bonds in terms of mutual rights or obligations, participants see humankind as being divided into two classes that remain inextricably bound to each other: you’re either predator or prey. Consequently, ‘survival of the fittest’ is the real name of the game, and everyone is ‘fair game’.

The 2021 Netflix series Squid Game provides an interesting variation on the battle royal trope. The titular contest’s 456 players are initially unaware that they are playing an elimination tournament, or that they will end up needing to turn on (and pile on top of) fellow combatants. Unlike Battle Royale or The Hunger Games (Gary Ross, 2012), the South Korean series is not about a group of young people taken against their will and forced to play death matches against one another; this particular game plays by its own rules, and it is worth noting what they are in advance:

• The participants are unsuspecting adults from various age brackets and backgrounds who have been tricked into playing deadly children’s games on a remote island. The only thing they have in common is that they are all in dire financial straits, and have been promised a way out of the lion’s mouth via a cash prize.

• When the first round of surviving players realise what is at stake – their own lives – they are given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity: they can choose either to not play anymore or to keep playing for the ever-expanding cash prize – eventually totalling ₩45.6 billion[10]Around A$53 million, at the time of writing. – that is literally dangling over their heads like a sword of Damocles.

• Returning players are subsequently forced to compete against one another to survive the five remaining elimination rounds.

• There is no penalty for eliminating other players in between games. Not playing by the rules is one of the rules of the game – and some of the adults try to game the system by levelling the field in other ways.

Squid Game complicates its battle royal by including an unspoken (and paradoxical) rule made famous by the reality TV show Survivor: if players want to survive elimination rounds, they’ll need to form alliances and look out for one another. Since they’re all playing the long game, though, they’ll also need to go on to eliminate the very people responsible for their survival. Indeed, treating other people as a means to an end – as mutually beneficial and/or exploitable – is the overriding goal of the contest. Although it has been claimed that the violent series is itself exploitative,[11]See, for example, Mike Hale, ‘Haven’t Watched Squid Game? Here’s What You’re Not Missing.’, The New York Times, 11 October 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/arts/television/squid-game-violence.html>, accessed 24 November 2021. Squid Game is careful not to endorse cynical worldviews like ‘the end justifies the means’ or assert that violence as entertainment is socially redeemable. The series instead delineates emergent gameplay via the competing players’ interactions and dynamics.

Squid Game is primarily interested in exploring the genuine feelings of affinity and enmity that emerge during tournaments involving duplicitous individuals and/or situational ethics. The series’ own endgame is to show the corrosive effects that the contest’s shifting power dynamics have on tenuous alliances and surviving players. Consequently, Squid Game becomes an allegory about a different kind of ‘game’[12]Games as social allegory have a long and varied history, and have themselves become contested terrain across many social fields, ranging from economics and law to philosophy and sociology. See, for example, John Cirace, Law, Economics, and Game Theory, Lexington Books, London, 2018. – the difficulties of surviving the killing fields of modern capitalism.[13]Patrick Frater, ‘Squid Game Director Hwang Dong-hyuk on Netflix’s Hit Korean Series and Prospects for a Sequel (EXCLUSIVE)’, Variety, 24 September 2021, <https://variety.com/2021/global/asia/squid-game-director-hwang-dong-hyuk-korean-series-global-success-1235073355/>, accessed 24 November 2021. Impersonal market forces and free-for-all trade practices are, in the show’s portrayal, the ultimate battle royal.

Squid Game becomes an allegory about a different kind of ‘game’– the difficulties of surviving the killing fields of modern capitalism.

Squid Game allegorises capitalism by depicting the ways in which it preys – and wreaks havoc on – the poor, weak and defenceless. In the battle royal that is global capitalism, there are already clear winners and losers; and, in the series, all of these enslaved ‘losers’ are simply being further exploited by their bored capitalist overlords for (more) fun and games. As writer/director Hwang Dong-hyuk notes, Squid Game is

an allegory or fable about modern capitalist society, something that depicts an extreme competition, somewhat like the extreme competition of life. But I wanted it to use the kind of characters we’ve all met in real life.[14]Hwang Dong-hyuk, quoted in Frater, ibid.

Perhaps that’s why the heightened reality of Squid Game has become such a global phenomenon and was number one with a bullet (to the head) in ninety countries[15]See Paul Tassi, ‘Squid Game Is Now the #1 Show in 90 Different Countries’, Forbes, 3 October 2021, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2021/10/03/squid-game-is-now-the-1-show-in-90-different-countries/>, accessed 24 November 2021. – for millions of viewers, trapped in their own day-to-day contests, there is a recognition of the rigged game that they too have been forced to play.

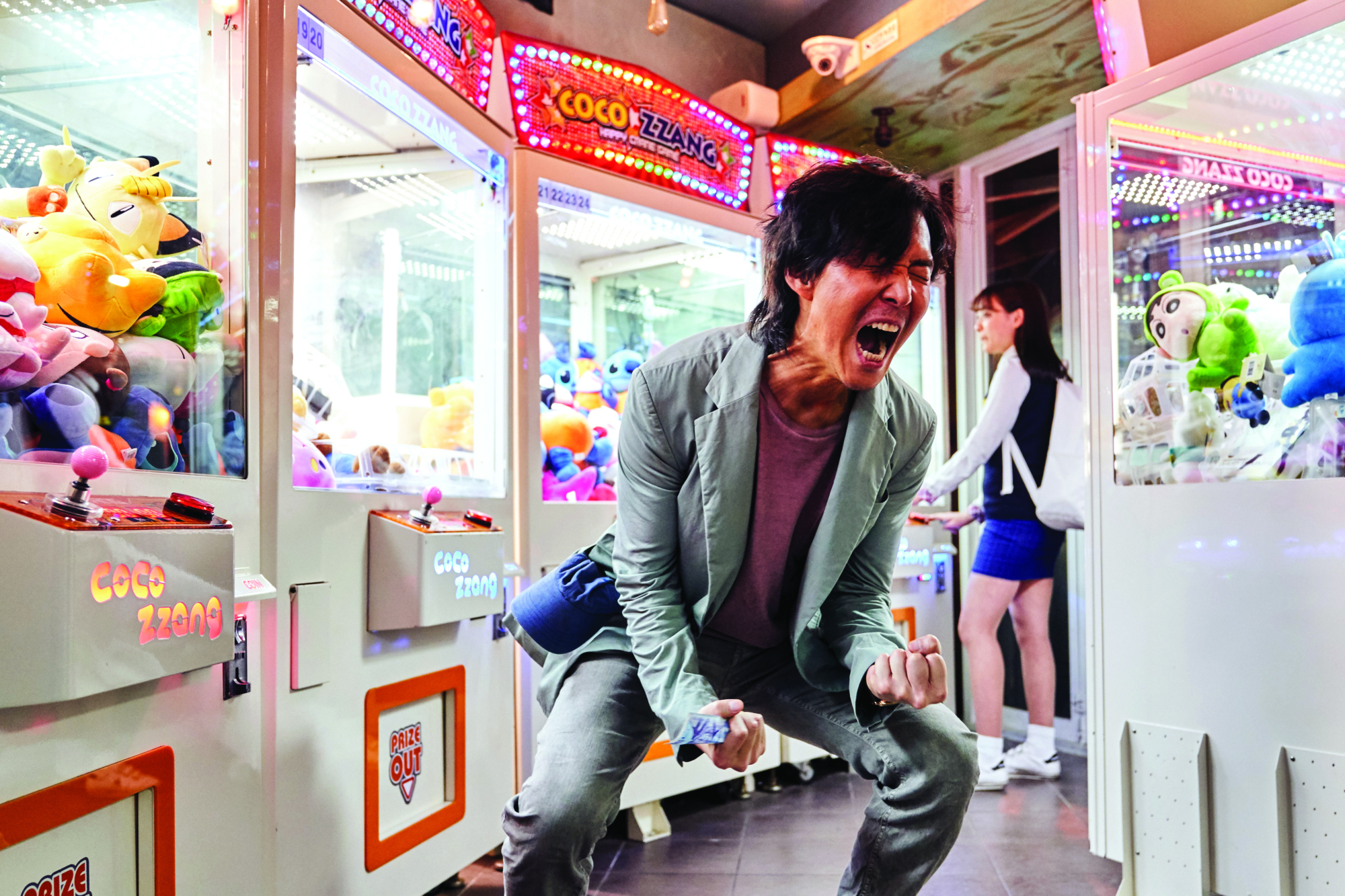

We learn from the outset that the poorest players have already been playing a game designed to work against their best interests. The series’ main protagonist, Seong Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), is a down-on-his-luck chauffeur looking for an easy win on an uneven playing field. The (initially) unsympathetic divorcee is literally gambling with his life: stealing from his sick elderly mother, and so in debt to loan sharks that he can’t afford to buy his neglected daughter a birthday present. This derelict dad/son is a real ‘loser’ who can’t catch an even break, and his freefall coincides with losing his factory job after a failed workers strike. He thereby becomes a prime target for recruitment for the game’s rich organisers, and finds himself being sold another bill of goods: a pot of gold at the end of his doom and gloom.

Squid Game arguably makes a curious misstep by revealing the show’s main protagonist in the first episode: it lets us know in advance who is going to be the ‘last man standing’. A more astute approach might have attempted to divide viewers’ attention and loyalties – if only to test our own characters or emotional investment in the series’ (financial) stakes. Nonetheless, Squid Game course-corrects its seemingly skewed approach by formally introducing us to some of the other major players in its second episode. When the shell-shocked survivors subsequently vote themselves off the island by a majority of one, the series also gives viewers time to take stock of their situation. Some of the people we meet include: Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo), a childhood friend of Gi-hun and former head of an investment firm guilty of embezzlement and poor investments; Ali Abdul (Anupam Tripathi), a migrant worker being ripped off by his employer; Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Hoyeon), a North Korean defector and pickpocket trying to reunite her family through the human smugglers extorting her; Oh Il-nam (Oh Yeong-su), a dying elderly man wanting to feel alive again; and Jang Deok-su (Heo Sung-tae), a gangster who has forgotten the golden rule of honour among thieves. While we meet all these people again, it should also come as no surprise whom the final two players turn out to be: to maximise dramatic effect (or irony), lifelong friends Gi-hun and Sang-woo are forced to play their beloved childhood ‘squid game’ as a real fight to the death.[16]The series begins with a black-and-white sequence of the two young friends (among others) playing a game that culminates in mock death.

The return to the mainland serves three dramatic purposes: to show us that the lives the characters have returned to is a fate worse than death; that they’ve all been similarly compromised by the predatory choices they’ve made or the exploitative paths they’ve found themselves on; and that the players choose to return to the deadly game in the vain hope that they might be able to salvage something from the wreckage of their lives.[17]The players’ return to normal society serves a fourth dramatic purpose: an alerted police officer follows Gi-hun in search of his missing brother. The officer’s ‘undercover operation’ essentially serves to show viewers what is going on behind the scenes at the elimination tournaments. Unfortunately, this story is also the series’ weak link – it goes nowhere fast, and seems intended to provide one of two predictable ‘twists’.

Although the rules appear to be equally arbitrary, the contest’s host falsely claims that their game-world is a level playing field – that everyone is fair game.

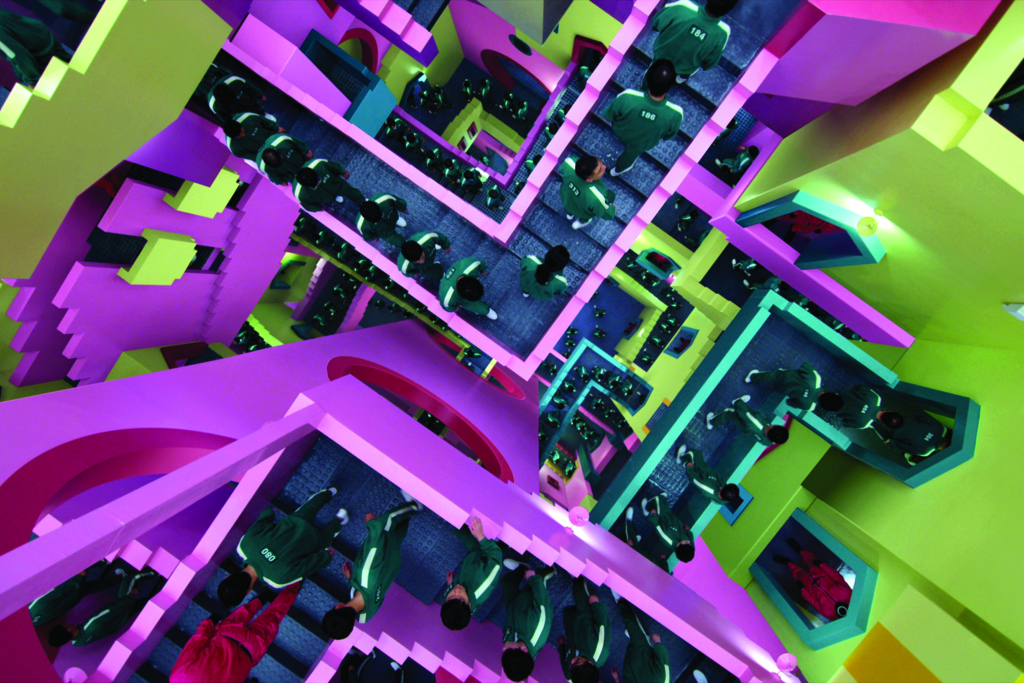

Squid Game’s elaborately designed game-world maps out its treacherous moral terrain in aesthetic terms. As series production designer Chae Kyun-sun notes, the interplay between physical spaces and stylised imagery was arranged to accommodate the show’s overarching themes.[18]Zoe Hewitt, ‘Squid Game: How the Show’s Larger-than-life Set Design Came Together’, Variety, 15 October 2021, <https://variety.com/2021/artisans/news/squid-game-sets-production-design-1235090060/>, accessed 24 November 2021. While the candy-coloured visual scheme suggests that the players have entered a children’s storybook, Squid Game’s interior designs more anticipate the twisted fairytales of the Brothers Grimm. An MC Escher–style spiral staircase figures centrally and relativises the state of play: ascending and descending players are all similarly caught in an inescapable death loop. Squid Game’s painstaking mise en scène – compositions, sets, props, colours, costumes, etc. – work together to disorient the viewer, heighten the tension and amplify the terror. The game-world is a series of elaborate death traps, comprised of spaces designed to capture and torture its unsuspecting victims and situations lying in wait to further surprise and destroy them. The game’s dwindling player-base is under constant surveillance, and subjected to coercive controls and summary executions. Although the rules appear to be equally arbitrary, the contest’s host falsely claims that their game-world is a level playing field – that everyone is fair game because everyone has an equal chance to win:

Every player gets to play a fair game under the same conditions. These people suffered from inequality and discrimination out in the world, and we’re giving them one last chance to fight fair and win.

The truth, of course, is that they’re not playing a game ‘fair and square’. A genetic and social lottery is already in play, and has determined their starting positions and likely outcomes. Although these unlucky men and women need to be team players to survive odds that are deadset against them, the game adds insult to injury by turning teammates against each other. Up until the series’ pivotal – and best – sixth episode, the players are able to present a united front: they need allies to survive elimination rounds (and/or one another). Previously, the players have invariably been asked to partner up with one of their teammates, and led to believe that the partnerships will continue in the spirit of collaboration and camaraderie; but, in this episode, a game of marbles reveals that everyone has been competing in a battle royal all along.

In depicting this melancholic death match, the sixth episode simultaneously does two very interesting things: it exposes the players’ pretence of ‘united we stand, divided we fall’; and it reminds viewers that the rules of the game were designed to win participants over and make them equally complicit in its (unfair) system. Indeed, this is one reason why capitalism has proven to be such an international success against competing economic systems: its ‘invisible hand’ confers advantages to society’s supposedly more deserving members, all while ostensibly directing mutual self-interest in service of the greater good.[19]For further discussion of the role of the concept of self-interest in capitalism, see Susumu Egashira, et al. (eds), A Genealogy of Self–interest in Economics, Springer, Singapore, 2021. Consequently, a competitive marketplace doesn’t so much mark the place between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ people or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ decisions – it merely ensures supposed fair play by legitimising the dividing line between society’s ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. We’ve already seen that many of these characters have been morally compromised by systemic inequalities and/or were victims of circumstance; in Episode 6, we see them defaulting to their worst impulses or struggling with the myths of meritocracy and self-determination. As such, it is unfortunate to see the series itself take a turn for the worse in the remaining three episodes.

Squid Game conveniently displaces its observations and concerns about the role individuals play in determining distributive justice (that is, allocation of rewards and punishments through socially sanctioned actions). Although the series never loses sight of the fact that these desperate individuals have chosen to compete against one another in death matches, its introduction of crass American VIPs into the game minimises the existing players’ collective accountability in the corrupt (and corruptible) economic system they’re also trying to benefit from.[20]For further discussion of personal responsibility within power structures, see Carl Knight & Zofia Stemplowska (eds), Responsibility and Distributive Justice, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 2011. The series’ social allegory transfers the thematic emphasis to competitiveness as spectator sport – Our capitalist overlords are emperors in new clothes, and we are their mere playthings! – and the narrative’s ‘last person standing’ motif raises the risible possibility of retributive justice. A significant irony is that Squid Game itself tests the limits of mass entertainment and consumption in that it is produced, distributed and consumed on a streaming platform that remains committed to a corporatist global culture.[21]See Ralph Jones, ‘How Netflix Took Over the World’, VICE, 10 September 2020, <https://www.vice.com/en/article/bv8kev/how-netflix-took-over-the-world>, accessed 24 November 2021.

Witness the contradictions at the heart of the show’s (capitalist) enterprise: instead of facilitating widespread discourse about class resentments or systemic inequalities, Netflix’s ‘impact value’[22]See Lucas Shaw, ‘Netflix Estimates Squid Game Will Be Worth Almost $900 Million’, Bloomberg, 17 October, 2021, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-17/squid-game-season-2-series-worth-900-million-to-netflix-so-far>, accessed 24 November 2021. has primarily functioned as a safety valve. Squid Game has thereby acted as a highly profitable pressure release: it has released rising anger and despair back into global capitalism’s oppressive, fail-safe system in the form of mass consumerism and entertainment. And although Squid Game’s sympathies purportedly lie with the oppressed, it cannot avoid turning the millions of viewers at home into members of a digital colosseum deriving pleasure from watching other people’s suffering. Moral degradation is thus transformed into a spectator sport, as many of the show’s visibly shamed[23]The concept of shame is integral in East Asian cultures, and the characters’ shame here appears to be twofold: shame at being one of society’s failures and shame at resorting to illicit activity to succeed. See Ying Wong & Jeanne Tsai, ‘Cultural Models of Shame and Guilt’, in Jessica L Tracy, Richard W Robins & June Price Tagney (eds), The Self–conscious Emotions: Theory and Research, Guilford Press, New York & London, 2007, pp. 209–23. losers appear to be getting their just deserts. Equally contradictory is the role that consumers have freely played in their own systemic oppression via other entertaining diversions and sensations. If the billions of TikTok views of shared videos, memes and fan edits of the show are any indication,[24]When I began writing this piece, there were ‘only’ 27 billion TikTok views for videos with the hashtag #squidgame; when I finished writing, there were 61 billion (and there are likely to be 100 billion by the time you’re reading this). See #squidgame tag search, TikTok, <https://www.tiktok.com/tag/squidgame>, accessed 25 November 2021. we’re more than happy to amuse ourselves to death[25]Media theorist Neil Postman contrasts the dystopias posed in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty–Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, observing that future citizens are far more likely to encounter the latter’s scenario than the more obviously oppressive regime envisioned in the former. As he goes on to argue, it’s our desire to be diverted and distracted by new sensations and technology – and thus, our capacity to love our oppression – that poses the real threat to our freedoms. See Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, Penguin Books, New York, 1985. at our own expense.

Endnotes

| 1 | See John S Nash, ‘Wrestling with the Past: The Bizarre Origins of the Battle Royal – Part One’, Cageside Seats, 9 March 2013, <https://www.cagesideseats.com/2013/3/9/4028970/battle-royal-WWE-Boxing-wrestling-with-past-origins-history-combat-sports-part-one>, accessed 24 November 2021 |

|---|---|

| 2 | See, for example, Stephen King’s The Long Walk and The Running Man and Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games. |

| 3 | See, for example, The Most Dangerous Game (Irving Pichel & Ernest B Schoedsack, 1932), The Running Man (Paul Michael Glaser, 1987), Hard Target (John Woo, 1993), The Hunger Games (Gary Ross, 2012), As the Gods Will (Takashi Miike, 2014) and The Hunt (Craig Zobel, 2020). |

| 4 | This is particularly prevalent in Japanese anime series: see, for example, Gantz, Kaiji: Ultimate Survivor, Liar Game, Fate/Zero and Death Parade. Other recent television shows that deal with this theme are 3% and Alice in Borderland. |

| 5 | See, for example, PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds, Fortnite, Call of Duty: Warzone and Apex Legends. |

| 6 | Koushun Takami, Battle Royale, trans. Yuji Oniki, VIZ, San Francisco, 2003 [1999]. |

| 7 | Kathleen Coleman, ‘Spectacle’, in Alessandro Barchiesi & Walter Scheidel (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2010, pp. 651–71. |

| 8 | See Sergio Lussana, ‘To See Who Was Best on the Plantation: Enslaved Fighting Contests and Masculinity in the Antebellum Plantation South’, The Journal of Southern History, vol. 76, no. 4, p. 917. The website of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia also provides extensive examples of advertisements for battles royal and excerpts from slave interviews; see Franklin Hughes, ‘Negro Battle Royal – May 2014’, Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia website, May 2014, <https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2014/may.htm>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 9 | ‘Battle Royal’ is the title of the first chapter of Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, which describes the unnamed Black protagonist’s experience of fighting other blindfolded African-American men for the entertainment of rich white audiences. ‘Live with your head in the lion’s mouth’ is the deathbed advice given to him by his grandfather, a former slave. Ellison, Invisible Man, New York, Vintage Books, 1989, p. 16. |

| 10 | Around A$53 million, at the time of writing. |

| 11 | See, for example, Mike Hale, ‘Haven’t Watched Squid Game? Here’s What You’re Not Missing.’, The New York Times, 11 October 2021, <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/11/arts/television/squid-game-violence.html>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 12 | Games as social allegory have a long and varied history, and have themselves become contested terrain across many social fields, ranging from economics and law to philosophy and sociology. See, for example, John Cirace, Law, Economics, and Game Theory, Lexington Books, London, 2018. |

| 13 | Patrick Frater, ‘Squid Game Director Hwang Dong-hyuk on Netflix’s Hit Korean Series and Prospects for a Sequel (EXCLUSIVE)’, Variety, 24 September 2021, <https://variety.com/2021/global/asia/squid-game-director-hwang-dong-hyuk-korean-series-global-success-1235073355/>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 14 | Hwang Dong-hyuk, quoted in Frater, ibid. |

| 15 | See Paul Tassi, ‘Squid Game Is Now the #1 Show in 90 Different Countries’, Forbes, 3 October 2021, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/paultassi/2021/10/03/squid-game-is-now-the-1-show-in-90-different-countries/>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 16 | The series begins with a black-and-white sequence of the two young friends (among others) playing a game that culminates in mock death. |

| 17 | The players’ return to normal society serves a fourth dramatic purpose: an alerted police officer follows Gi-hun in search of his missing brother. The officer’s ‘undercover operation’ essentially serves to show viewers what is going on behind the scenes at the elimination tournaments. Unfortunately, this story is also the series’ weak link – it goes nowhere fast, and seems intended to provide one of two predictable ‘twists’. |

| 18 | Zoe Hewitt, ‘Squid Game: How the Show’s Larger-than-life Set Design Came Together’, Variety, 15 October 2021, <https://variety.com/2021/artisans/news/squid-game-sets-production-design-1235090060/>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 19 | For further discussion of the role of the concept of self-interest in capitalism, see Susumu Egashira, et al. (eds), A Genealogy of Self–interest in Economics, Springer, Singapore, 2021. |

| 20 | For further discussion of personal responsibility within power structures, see Carl Knight & Zofia Stemplowska (eds), Responsibility and Distributive Justice, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK & New York, 2011. |

| 21 | See Ralph Jones, ‘How Netflix Took Over the World’, VICE, 10 September 2020, <https://www.vice.com/en/article/bv8kev/how-netflix-took-over-the-world>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 22 | See Lucas Shaw, ‘Netflix Estimates Squid Game Will Be Worth Almost $900 Million’, Bloomberg, 17 October, 2021, <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-10-17/squid-game-season-2-series-worth-900-million-to-netflix-so-far>, accessed 24 November 2021. |

| 23 | The concept of shame is integral in East Asian cultures, and the characters’ shame here appears to be twofold: shame at being one of society’s failures and shame at resorting to illicit activity to succeed. See Ying Wong & Jeanne Tsai, ‘Cultural Models of Shame and Guilt’, in Jessica L Tracy, Richard W Robins & June Price Tagney (eds), The Self–conscious Emotions: Theory and Research, Guilford Press, New York & London, 2007, pp. 209–23. |

| 24 | When I began writing this piece, there were ‘only’ 27 billion TikTok views for videos with the hashtag #squidgame; when I finished writing, there were 61 billion (and there are likely to be 100 billion by the time you’re reading this). See #squidgame tag search, TikTok, <https://www.tiktok.com/tag/squidgame>, accessed 25 November 2021. |

| 25 | Media theorist Neil Postman contrasts the dystopias posed in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty–Four and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, observing that future citizens are far more likely to encounter the latter’s scenario than the more obviously oppressive regime envisioned in the former. As he goes on to argue, it’s our desire to be diverted and distracted by new sensations and technology – and thus, our capacity to love our oppression – that poses the real threat to our freedoms. See Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, Penguin Books, New York, 1985. |