The Australian Film Development Corporation was established by statute in 1970 “to encourage the making of Australian films and television and to encourage their distribution inside and outside Australia.” It is directed to have regard to the achievement of high technical and artistic standards. The Act provides guidelines for what constitutes “significant Australian content”. The AFDC is essentially a bank, lending or investing with the hope of return. The original budget was $1,000,000, granted in the 1970–71 Budget. Another $1,000,000 was made available for 1972–73. There was no suggestion that the Government would continue to grant Budget funds indefinitely. It was expected that the AFDC would live on the income derived from successful investments.

Election of a Labor Government means that larger sums will almost certainly be granted and that the AFDC will be encouraged to take some risks. The financial uncertainty of 1971–73 led the AFDC to pursue an extremely cautious investment policy. Most of the early investments provided advance moneys for television series. As the series were shown the AFDC was repaid by the television network.

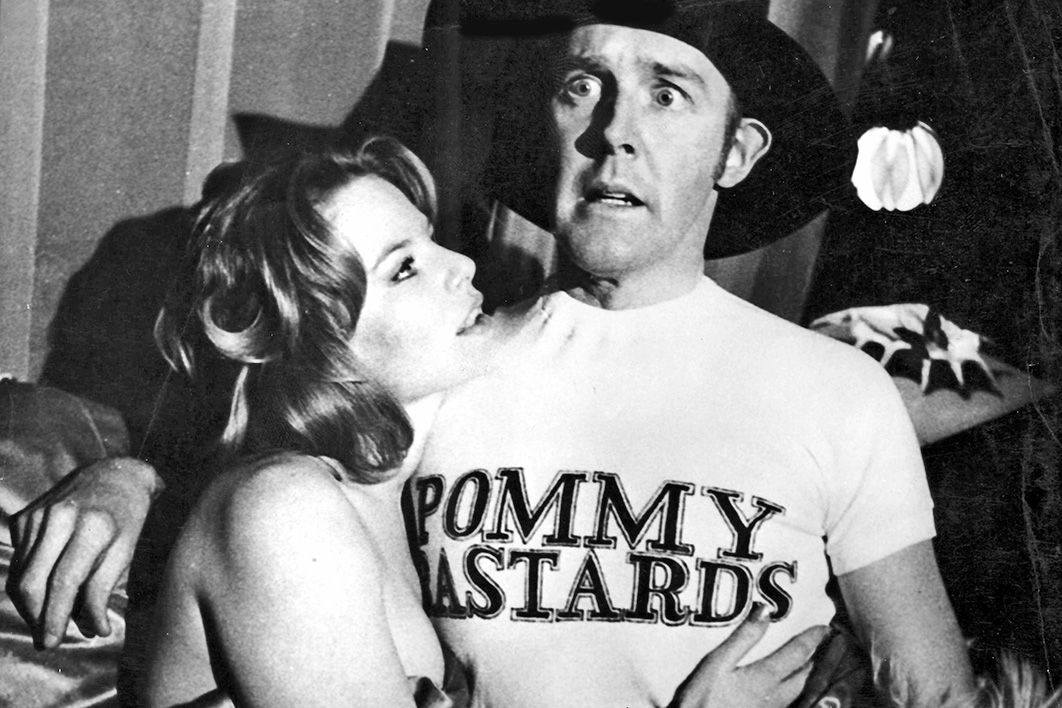

The first major investment was $250,000 in The Adventures of Barry McKenzie. The AFDC invests $100,000 into Sunstruck and $80,000 into The Australian Ark. Another $60,000 was lent to Porter Animation Ltd. for Marco Polo Jr.

The AFDC prefers to invest but will lend on adequate security where it lacks confidence in the project, or where the producer rejects investment (as happens sometimes when the producer is confident of a huge success).

This ultra-caution has been much criticised – rightly. The AFDC now intends to venture further into the high risk area by encouraging young film makers and looking for other investors. It will also invest in script development – providing funds for the re-writing of promising ideas.

The Film and Television Board of the Australian Council for the Arts will continue the Experimental Film Fund and the Film and Television Development Fund. These funds began under the original Australian Council in 1970. In 1971 they were transferred to the Interim Council for the National Film and Television School. The new Board is now functional and the Fund is back in action after some months in limbo.

In 1970–72, $115,000 was provided for conventional production; $21,000 for script development and $404,000 for the Experimental Film Fund. These moneys were provided as grants, not investments.

In general, the AFDC and the Film and TV Development Fund have been disappointed in the quality of the projects submitted. Poor scripts were an element in this. The major failing seemed to be in the whole concept behind projects. Too many seemed to be “committee” films in which the starting point is a desire to exploit the market with an ostensibly “sure-fire” formula. Having worked out an idea, the next step is to find a writer to bash out a treatment. Often to disguise the thinness of ideas or of characterisation such committees propose an exotic background – the outback, Barrier Reef, speedboat chases on Sydney Harbour.

I would like to encourage more films that start with a writer’s confidence that what he is writing has something to offer. I would prefer to see films based on a writer’s vision, obsessional or not, than films based on the acquisitive urge of used car salesmen and property developers. Australia is still an unexplored continent. I would like to encourage some expeditions into our own interiors. Most scripts reflect the gentle banalities of Australian life. But as Flaubert demonstrated in Madame Bovary a study of banality does not have to be banal itself. Many scripts try to disguise the banality by stressing picturesque setting, or putting characters in fancy dress.

Our one major success story so far, Barry McKenzie, is a curious mixture of an obsessional vision of an isolated writer (perhaps a genius) and a commercialised treatment. But the foundation was there in a very funny script, thought out with extreme care. The last thing the AFDC wants is to spawn a long series of Bazza films. That one is probably sui generis.

Spectacular or picturesque films cost a lot to make anyhow. Deep Throat which is entirely composed of ingredients you can find at home, cost – it is claimed – $17,000 and has grossed $4,000,000 (U. S.)

In the new look methods of the AFDC we want to encourage writers to pour their guts out in scripts which they really believe in. If they can convince us the Corporation will then look for backers and, in conjunction with the writer, seek a director, cameraman – in other words, put a package together.

There are many processes in Australian life which have never been seriously examined, for example, the learning process, the economic process, the political process, the occasional crisis of conscience, the impact of religion, say as a socially divisive force, the breakup of marriage, poverty, the aged, boredom, crime (other than what the French call policiers). Our comedy so often deteriorates into farce. I cannot recall the last example of wit or irony in a script.

The great bulk of applications to the AFDC have been rejected. The main reasons are:

1. Not satisfying the test of Australian content in the Act.

2. Dissatisfied with budgeting arrangements – many are quite implausible.

3. Not satisfied about the applicants’ capacity.

4. Scripts not good enough.

My own reaction in examining many scripts is to echo Truman Capote in another context: “This is not writing. This is typing”.

In recent months there has been a sharp decline in the number of projects submitted.

There has never been a time when the general level of first release films throughout the world has been higher. If Australia is going to make its mark – and there can be no certainty – in world film we cannot afford to compromise on quality.