Stepping into the aptly named, but decidedly uncinematic, SpACE @ Collins during the second week of the 2018 Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), I was greeted in the dim light by two bodies with heads rotating, standing in separate circles on the floor. A handful of others were waiting silently. I became immediately aware that this was not the usual communal ritual of festival film-watching, but something more individual, more internal.

Documentary filmmaking – from the observational work made in the 1960s through to the digital formats of today – has often sought what Richard Leacock has called ‘the feeling of being there’.[1]Richard Leacock, ‘A Search for the Feeling of Being There’, in Michael Tobias (ed.), The Search for ‘Reality’: The Art of Documentary Filmmaking, Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City, CA, 1998, p. 43. Our increasing interest in immersive forms, manifesting in the contemporary use of ambisonic and binaural audio as well as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies, has continued this tradition through what researchers Matthew Lombard and Theresa Ditton have termed ‘presence’: a mediated experience that feels ‘natural’, ‘immediate’, ‘direct’ and ‘real’ – in other words, one that feels unmediated by technology.[2]Matthew Lombard & Theresa Ditton, ‘At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence’, Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, vol. 3, no. 2, 1 September 1997, https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/3/2/JCMC321/4080403, accessed 25 October 2018. While technology is a key means through which the space between the self and the represented world has been reduced, this sense of ‘being there’ has also been achieved through other strategies that shift away from the indexical image and documentary ‘realism’, such as experimental and animated techniques.

The term ‘virtual reality’ can refer to a number of different technologies. Mandy Rose, co-director of i-Docs, a UK-based biennial interactive and immersive documentary symposium, identifies three VR categories. The first and most readily encountered is the 360-degree or ‘wraparound’ video, which the viewer engages with from a fixed point. While levels of production and sophistication range greatly, this is the most accessible format and therefore provides lower barriers to entry for interested filmmakers. The second uses computer-generated imagery (CGI) uploaded onto a game engine. This format requires a powerful computer, to which the audience is tethered, and makes use of visual hotspots, which can activate new images and scenes; hand controllers that viewers can use to interact with the space; and limited physical movement. The third form of VR uses volumetric capture that maps the audience’s spatial and kinetic data, thereby allowing for increased interactivity and creating a more individuated experience.[3]Mandy Rose, ‘The Immersive Turn: Hype and Hope in the Emergence of Virtual Reality as a Nonfiction Platform’, Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 135–6.

Although still an emergent and unstable form, VR – in its current iteration – has seen a rapid uptake, bolstered by some of the grand claims about what it can do. Most commonly, proponents of VR have made assertions about the ability of this mutating medium to elicit empathy.

Although still an emergent and unstable form, VR – in its current iteration – has seen a rapid uptake, bolstered by some of the grand claims about what it can do. Most commonly, proponents of VR have made assertions about the ability of this mutating medium to elicit empathy. In his notable 2015 TED Talk on the subject, VR innovator Chris Milk outlines that such empathy claims derive from the fact that VR gives rise to an enhanced sense of being in the world, rather than foregrounding edges and separateness.[4]Chris Milk, ‘How Virtual Reality Can Create the Ultimate Empathy Machine’, TED, March 2015, <https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine>, accessed 25 October 2018. Similarly, in his study comparing three forms of viewing experiences – VR through a headset, a 360-degree desktop version and a newspaper – journalist Dan Archer writes that the level of focus and immersion enabled by VR can create a greater feeling of identification and a desire to know more about the subject. Archer claims, however, that empathy is overused as a metric for appraising VR, and that story is a stronger indicator of a work’s immersive potential.[5]Dan Archer, ‘Dismantling the Metrics of Empathy (in 360 Video)’, Immerse, 19 May 2018, <https://immerse.news/dismantling-the-metrics-of-empathy-in-360-video-b03d013123ae>, accessed 25 October 2018. And researcher Janet Murray suggests that empathy can be fostered by ‘find[ing] the fit between the affordances of the co-evolving platform and specific expressive content – the beauty and truth – you want to share that could not be as well expressed in other forms’.[6]Janet H Murray, ‘Not a Film and Not an Empathy Machine’, Immerse, 7 October 2016, <https://immerse.news/not-a-film-and-not-an-empathy-machine-48b63b0eda93>, accessed 25 October 2018.

Recently, major film festivals have been including diverse side programs centring on VR – including MIFF, whose 2018 slate showcased a number of projects that push technology into new areas. Admittedly, it was the first time I had attended the festival’s VR sessions, intrigued to compare some of these novel ways of making and using technology with some of my previous, underwhelming VR experiences, which felt clunky and were often interrupted by ambient noise, ill-fitting headsets and crashing computers. I was sceptical but open to changing my mind.

Entering a world: Mind at War

Of MIFF 2018’s VR offerings, I was most keen to try the single-session projects that use CGI – the second of the aforementioned types – despite their relatively expensive cost-per-minute compared to that of a traditional film. The first of these was Mind at War (2017).This twenty-two-minute project by Australian interactive artist Sutu (Stuart Campbell) tells the story of US Iraq veteran Scott England and his experience of post-traumatic stress disorder following his period of service. The story is told through voiceover comprising audio compiled by England on a recorder that Sutu had sent him. The narrative traverses England’s memories of a childhood spent among nature and his enlistment in the army after losing his construction job two weeks before his wedding, through to basic training, relationship breakdown, the horrors of war, homelessness, eventual confrontation with depression and subsequent attempts at recovery through returning to nature.

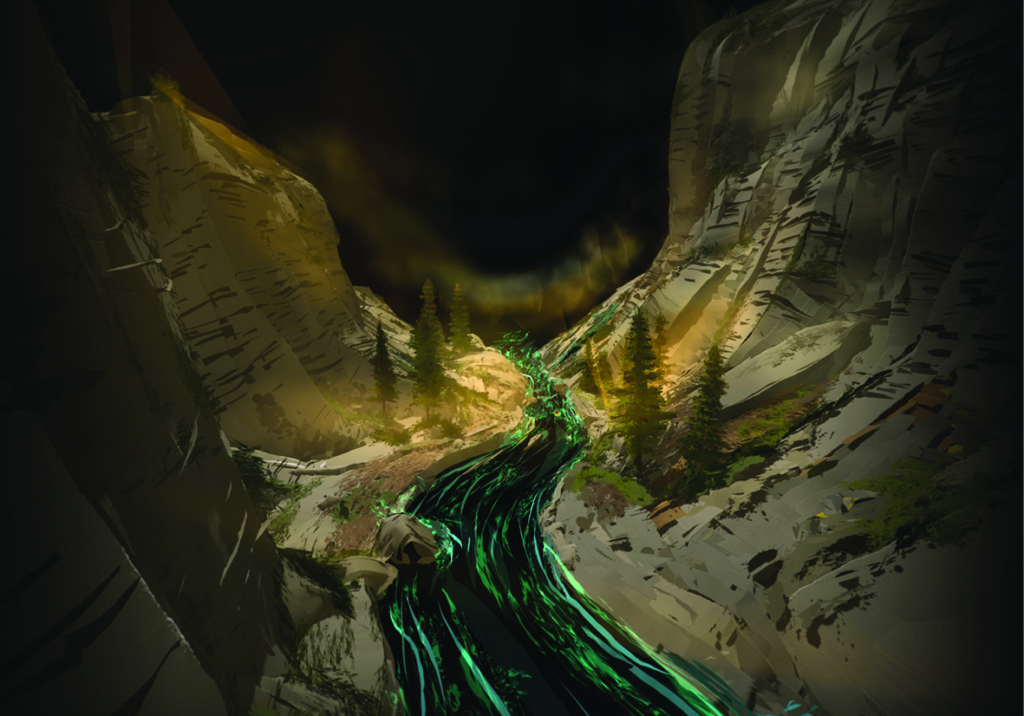

Mind at War does not attempt to show viewers the real world, instead presenting a series of 3D tableaux, created using the application Tilt Brush, that surround us in stillness. The experience positions us in what feels like a graphic diorama, in another place and time – we are granted entry into the mind of England as part of what Kate Nash calls an ‘as if’ moment.[7]Kate Nash, ‘Virtual Reality Witness: Exploring the Ethics of Mediated Presence’, Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 119–31. In this stilled world, the voice becomes the focal point, and the VR mode allows for Lombard and Ditton’s ‘presence’ – as Rose would characterise it, we are immersed in a world rather than merely watching events happen on screen.[8]Rose, op. cit., p. 136. The world Sutu has created brings to mind those of other animated documentaries that deal with trauma, such as Ari Folman’s Waltz with Bashir (2008) or Dennis Tupicoff’s His Mother’s Voice (1997). As film academic Annabelle Honess Roe has suggested, animation foregrounds the importance of sound and the voice by situating them in a non-live-action body; much like Rose, she posits that the emphasis is not only on the ‘world out there’ but also the ‘world in here’.[9]Annabelle Honess Roe, Animated Documentary, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2013, pp. 15, 26, emphasis removed. Additionally, she contends that the animated form ‘shifts and broadens the limits of what and how we can show about reality by offering new or alternative ways of seeing the world’.[10]ibid., p. 2. The drawn world of Mind at War affords us a nearness and more intimate access to the first-person testimony.

A recurring motif in the film is that of a campfire, which doubles as a hotspot that then launches into new chapters or scenes. The campfire is significant, as it signifies a ‘home’ point as well as togetherness and storytelling. It also reflects how England first met Sutu: it was while sitting by a campfire one night that England told Sutu about his life. This was the beginning of what later became this project. Much like it did for the pair, the campfire draws us in, as does this immersive experience of a story that we might not otherwise have engaged with.

Perspective shift: Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now

Over the past year, I’ve been fortunate to have heard some of the leading practitioners, theorists and facilitators of VR storytelling engage in discussions and debates around more expanded ways of thinking about the medium. During her visit to Melbourne in March last year, Ingrid Kopp, co-director of South African VR and AR storytelling organisation Electric South, spoke about VR being an empowering tool for reimagining the future, particularly in terms of moving beyond stereotypical depictions of non-dominant voices.[11]Ingrid Kopp, public talk, Docuverse, 8 March 2018. Also in March, at i-Docs, talk of VR expanded from claims about empathy and into more interesting territory, such as representation and imagination. In particular, Carmen Aguilar y Wedge of Hyphen-Labs spoke about the interdisciplinary collective’s mixed-reality project NeuroSpeculative AfroFeminism (2016), asserting that, by positioning the audience as a black woman – an identity that is doubly marginalised in Western society – we are forced to imagine what it’s like to have a black body. Aguilar y Wedge contends that this decreases prejudice or bias, arguing that we ‘fear what we don’t know’, but that, through simulated experiences, we can interact with or adopt the perspective of communities we might not have been exposed to, thereby ‘challeng[ing] perceptions of self and Other’.[12]Carmen Aguilar y Wedge, in the ‘At the Intersection of Technology, Art, Science & the Future’ panel, i-Docs, Bristol, 2018, available at <https://vimeo.com/271878248>, accessed 25 October 2018.

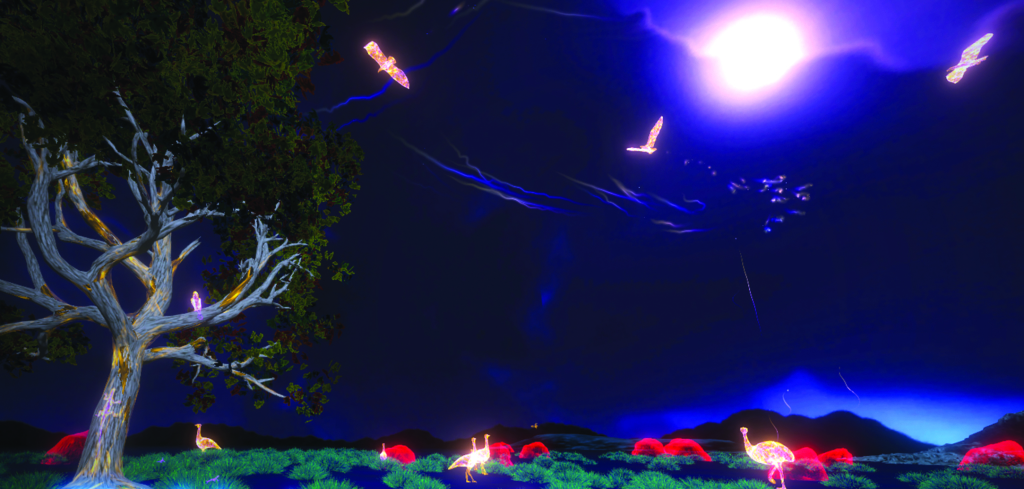

On my fourth day of MIFF VR activities – this time equipped with headset, headphones and hand controllers – I entered the neon-animated world of Tyson Mowarin’s Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now (2018). In this work, the audience is framed as a visitor to another world: not as a coloniser, but as a guest taken on a voyage of discovery. This film taps into Kopp’s and Aguilar y Wedge’s ideas about embodiment and perspective shift; I gave over control, and listened and acted in accordance with the directions of the guide on screen. ‘Thalu’ means ‘totem’ in the Ngarluma language of the western Pilbara region; however, the translation doesn’t exactly encompass the full meaning of the word, which also refers to ancient Aboriginal ceremonial sites.[13]‘World Premiere of Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now’, media release, Screenwest, 2 August 2018, <https://www.screenwest.com.au/news-events/2018/08/world-premiere-of-thalu-dreamtime-is-now/>, accessed 25 October 2018. Mowarin’s work blends traditional Dreamtime stories with futuristic visions and an aesthetic that feels very different from other Indigenous-themed VR works that I’ve encountered. The previous day, for instance, I had seen Dominic Allen’s live-action 360-degree VR project Carriberrie (2018), in which the viewer interacts with a range of scenes featuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander song-and-dance performances in different locations. The feeling I got was that of witnessing these scenes, however, rather than the sense of presence I had with Thalu. In Mowarin’s creation, the audience is central to the unfolding experience and afforded a certain agency within the simulated world through technology and interactivity.

I entered the neon-animated world of Tyson Mowarin’s Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now … framed as a visitor to another world: not as a coloniser, but as a guest taken on a voyage of discovery. This film taps into Kopp’s and Aguilar y Wedge’s ideas about embodiment and perspective shift.

Thalu was also illustrated by Sutu, but this dynamic work is quite distinct from the placid Mind at War; in fact, there were even occasions when I found my attention drifting away from Thalu’s guide and towards its brilliant, technicolour world.This project is decidedly multi-sensory: Using the hand controllers, I could make the winds rise and the birds fly. I could reach out to touch petroglyphs, which would then magically transport me through a neon-coloured swirling vortex into another dimension. Junctures between the virtual and the very real also came into play: One moment, I was vaguely self-conscious as I stood, waving my arms around, in a demarcated circle in the MIFF VR space. In another, I was stepping backwards, away from the imaginary edge of the Earth as it descended into the ground, the film almost inducing the sensation of vertigo.

*

As yet, it’s difficult to draw too many conclusions about the wider implications of VR as a tool for documentary. Due to VR works’ relatively short durations and the giddy thrill they elicit, I am reminded of Archer’s analogy of VR being akin to speed dating.[14]Archer, op. cit. Rather than being seduced by the novelty of the technology, it’s important that we consider what VR documentary can do and how we use it beyond its representational qualities and prospects, even if it is more immersive. Having said that, both Mind at War and Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now present documentary experiences that facilitate engagement with created worlds that feel unique to the medium and offer the feeling of being somewhere else.

Endnotes

| 1 | Richard Leacock, ‘A Search for the Feeling of Being There’, in Michael Tobias (ed.), The Search for ‘Reality’: The Art of Documentary Filmmaking, Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City, CA, 1998, p. 43. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Matthew Lombard & Theresa Ditton, ‘At the Heart of It All: The Concept of Presence’, Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, vol. 3, no. 2, 1 September 1997, https://academic.oup.com/jcmc/article/3/2/JCMC321/4080403, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 3 | Mandy Rose, ‘The Immersive Turn: Hype and Hope in the Emergence of Virtual Reality as a Nonfiction Platform’, Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 135–6. |

| 4 | Chris Milk, ‘How Virtual Reality Can Create the Ultimate Empathy Machine’, TED, March 2015, <https://www.ted.com/talks/chris_milk_how_virtual_reality_can_create_the_ultimate_empathy_machine>, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 5 | Dan Archer, ‘Dismantling the Metrics of Empathy (in 360 Video)’, Immerse, 19 May 2018, <https://immerse.news/dismantling-the-metrics-of-empathy-in-360-video-b03d013123ae>, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 6 | Janet H Murray, ‘Not a Film and Not an Empathy Machine’, Immerse, 7 October 2016, <https://immerse.news/not-a-film-and-not-an-empathy-machine-48b63b0eda93>, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 7 | Kate Nash, ‘Virtual Reality Witness: Exploring the Ethics of Mediated Presence’, Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 12, no. 2, 2018, pp. 119–31. |

| 8 | Rose, op. cit., p. 136. |

| 9 | Annabelle Honess Roe, Animated Documentary, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2013, pp. 15, 26, emphasis removed. |

| 10 | ibid., p. 2. |

| 11 | Ingrid Kopp, public talk, Docuverse, 8 March 2018. |

| 12 | Carmen Aguilar y Wedge, in the ‘At the Intersection of Technology, Art, Science & the Future’ panel, i-Docs, Bristol, 2018, available at <https://vimeo.com/271878248>, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 13 | ‘World Premiere of Thalu: Dreamtime Is Now’, media release, Screenwest, 2 August 2018, <https://www.screenwest.com.au/news-events/2018/08/world-premiere-of-thalu-dreamtime-is-now/>, accessed 25 October 2018. |

| 14 | Archer, op. cit. |