With the growing prevalence of subscription video-on-demand services such as Netflix, Stan and Amazon as well as the increase in online-only content on broadcast affiliates like ABC iview, what characterises a ‘web series’ remains up for grabs. For television scholar Aymar Jean Christian, the definition is broad, in that web series ‘combine the modus operandi of scripted television programming (series and serialization) with new formats (primarily short-form, due to fewer resources and perceptions of audience attention)’.[1]Aymar Jean Christian, Open TV: Innovation Beyond Hollywood and the Rise of Web Television, New York University Press, New York, 2018, p. 33. Unlike traditional broadcast television, which acted as gatekeeper to content, platforms for web series don’t necessarily differentiate between productions with huge resources and those made on student or shoestring budgets. And, while web series might once have been defined by their DIY aesthetic, progressively more money is being invested into Australian titles through state and national screen-funding bodies as well as new initiatives looking to reward work with established audiences.[2]A key example is Screen Australia’s Skip Ahead development program, run in partnership with Google; for more information, see ‘Skip Ahead’, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/television-and-online/production/special-initiatives/skip-ahead>, accessed 29 October 2019.

Over the past few years, the popularity and quantity of web series have rapidly expanded. However, as media researcher Whitney Monaghan observes, there continues to be a paucity of scholarly attention given to the form, with most studies that have existed to date focusing on the medium’s potential to cater for diverse and under-represented communities.[3]Whitney Monaghan, ‘Starting from … Now and the Web Series to Television Crossover: An Online Revolution?’, Media International Australia, vol. 164, no. 1, 2017, p. 83. For example, critic Stephanie Van Schilt suggests that, through affording ‘marginalised voices space to create content and reach audiences’, web series ‘reflect reality more readily than traditional television’.[4]Stephanie Van Schilt, ‘How to Talk Australians and the Rise of Web Series’, Kill Your Darlings, 3 October 2014, <https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/2014/10/how-talk-australians-rise-web-series/>, accessed 30 October 2019. But things move fast in the online space – something I witnessed firsthand at the seventh annual Melbourne WebFest,[5]Founded in 2013, Melbourne WebFest is the fourth such festival in the world and one of the largest of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere. Last year’s four-day festival included workshops, screenings, networking opportunities and an iview-sponsored pitching competition. See <https://www.melbournewebfest.com>, accessed 30 October 2019. which I attended last year. Of the Australian titles on offer, some were no longer self-funded, now receiving financial and/or distribution support from the likes of iview (Unboxed, Wrong Kind of Black), Comedy Central (Gocsy’s Classics), 10 play (Dee-Brief) and even YouTube itself (Over and Out). With this type of backing come slicker aesthetics, tighter scripting and higher production values. This, then, invites the question of whether web series still do provide more avenues not only for under-represented perspectives, but also for a variety of formats and styles. It is additionally worth interrogating the extent to which ‘web festivals’ – which, by definition, select and curate – program those products that have already garnered considerable support and viewership.

With these questions in mind, the selection of series on offer at Melbourne WebFest 2019 reflected a number of mainstream trends, which include the seemingly indefatigable true-crime genre, an interest in traditionally marginal communities and voices, and a ton of comedy. However, in a departure from their treatments in mainstream broadcast formats, the web series I discuss below have found ways to reinvigorate and subvert their subject matter. These include foregrounding rarely heard LGBTQIA+ voices from Pacific Island communities, presenting a low-budget parody tinged with social commentary that zings with its short episodic structure and offering new approaches to true crime. The five series explored here exemplify that the web-series format continues to be a space for the representation of non-mainstream voices and perspectives in front of and behind the camera. Further, they evidence that inventiveness can be harnessed through the medium’s relatively low barriers to production, and can lead to success regardless of the slickness of the final product.

Weaving Rainbows

https://thecoconet.tv/coco-series/weaving-rainbows/

Weaving Rainbows is a New Zealand documentary series recounting experiences of LGBTQIA+ Pasifika people.[6]‘Pasifika’ is a term originating from New Zealand used to describe people from the greater Pacific region, including Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, Tahiti and Hawaii; see ‘What Does Pasifika Mean?’, University of Otago website, <http://oil.otago.ac.nz/oil/module10/What-does-pasifika-mean-.html>, accessed 29 October 2019. Funded by NZ on Air, the program consists of five self-contained episodes that each focus on the trials and triumphs faced by one individual, often confronting cultural expectations and norms with positive narratives that affirm difference. The series can be accessed via The Coconet, a ‘virtual island homeland to engage with our global Pacific village’.[7]See The Coconet, <https://thecoconet.tv>, accessed 29 October 2019. Maintained by the collective Tikilounge Productions, the site hosts videos, vlogs and memes that cover everything from travel tips and songs, to recipes and history lessons for kids.

At the time of writing, the featured video on the front page of ‘Coco Series’ was the Weaving Rainbows episode on Asia Stanley, a Samoan fa‘afafine.[8]A fa‘afafine is a person who was assigned male at birth but lives as a woman – an identity that forms part of Samoan culture’s wider, non-Western conception of gender. For more, see Alan Weedon, ‘Fa‘afafine, Fakaleitī, Fakafifine – Understanding the Pacific’s Alternative Gender Expressions’, ABC News, 31 August 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-31/understanding-the-pacifics-alternative-gender-expressions/11438770>, accessed 29 October 2019. In this episode, which runs at just under fifteen minutes, Stanley talks about the complexities of her identity and the accompanying cultural expectations, her media career, and her love for her family and community. Intercut with this interview are scenes of her with loved ones, including her rugby-playing brothers, nieces and nephews; footage of her playing volleyball; and visuals of her media engagements. Stanley is also shown spending time with her community, a group of fellow fa‘afafine known as the Kingdom of the Amazons. The episode highlights that Stanley is deeply respected in her Samoan community and that, for her, family (both blood and chosen) is of utmost importance. Yet her story is tinged with melancholy – even when she expresses no apparent bitterness in revealing that, for a fa‘afafine like her, love is ‘a fairytale’.

While conventional in its approach to nonfiction storytelling, Weaving Rainbows sits very much within the documentary form’s tradition of bearing witness. And, as web series allow for more direct access to the means of production and distribution, they enable the stories of marginalised communities – such as queer Pasifika people – to be told more authentically. This resonates with one of the fundamental attributes of web series identified by Christian: that they can enable ‘new ways of producing content and new avenues to explore and challenge representations’.[9]Aymar Jean Christian, ‘Fandom as Industrial Response: Producing Identity in an Independent Web Series’, Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 8, special issue 1, 2011, <https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/250/237>, accessed 29 October 2019.

The Housemate

https://iview.abc.net.au/show/housemate

With a host who bears more than a passing resemblance to media personality Osher Günsberg, replete with snug-fitting suit, piercing looks and good hair, The Housemate is a snappy parody of the Bachelor and Bachelorette reality-TV juggernauts. Using similar musical cues and self-reflective musings on finding ‘the one’, this series takes the form of a competitive reality show whose winner will be granted the privilege of sharing an inner-city Melbourne house with stars Alex and Gemma (played by co-writers Alexandra Keddie and Gemma Bird Matheson). Produced by Chips & Gravy Films and available on iview, the six-part series starts with eight applicants (after three pull out before the proceedings); from a first-year arts student and a Sportsgirl retail assistant, to a pair of vegan chefs, a deadpan children’s-party planner and a healer-cum-musician-cum-bartender, each would-be housemate exemplifies tropes familiar to anyone with even a slight interest in reality TV. As per other shows of this genre, there are tasks and challenges – in this case, meal preparation and grocery shopping – that provide further clues as to the compatibility of the contestants. Gradually, the players are whittled down to the final three, who are bestowed the honour of the prized home visits. Finally, one lucky contestant is chosen. Yet there is a twist lying in wait, with the final scene further parodying the genre and its participants’ insatiable appetite for prime-time fame.

Each episode of The Housemate ranges from five to, for the finale, twelve minutes – a trait unique to web series. As media scholar Stayci Taylor suggests, unlike conventional broadcast television, web series tend to exhibit a flexibility in terms of episode length, and this is one of the typifying (and subversive) features of the form. Without rigid restrictions on duration, the formulas for writing and structure can be reimagined,[10]Stayci Taylor, ‘“It’s the Wild West out There”: Can Web Series Destabilise Traditional Notions of Script Development?’, paper presented at the Australian Screen Production Education and Research Association annual conference, Adelaide, 15–17 July 2015, pp. 4–5, <http://aspera.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Taylor-2015_v2.pdf>, accessed 29 October 2019. allowing each episode to be as long as it needs to be for storytelling purposes.

While The Housemate parodies the kind of content that dominates Australian commercial television, it also satirises the very real issue of housing affordability for young people. Although this series did receive funding from Screen Australia, its success comes not from its production values, but from its ability to blend the very relatable quest to find a room in a sharehouse with a canny knowledge of reality-TV tropes and comic timing. The Housemate may not bring anything particularly new to the genre’s format, but it is an enjoyable series that combines an awareness of popular culture with social critique.

The Twist

https://iview.abc.net.au/show/twist

With the true-crime industrial complex showing no sign of abating, the goal for creatives is to find new means by which to tell these stories. The Twist, produced by Broken Yellow and available on iview, is a fifteen-part series that, memorably, employs an animated aesthetic resembling paper collages. Each episode ranges from three to five minutes and is tightly written, often utilising nonlinear chronology and flashbacks. The stories, voiced by an omniscient narrator, follow the same format: each begins with three key ingredients that act as clues to the mystery and invite the audience to draw connections, before slowly piecing together the mystery. For example, ‘Who Killed Zoe Zou?’ opens with ‘a country drive, fresh air, a boot full of human bones’, and ‘Harry’s Secret’, with ‘lies, lovers and a deadly secret’. Most of the stories in The Twist are historical, with only two taking place in the last twenty years. The most recent tale, ‘The Woman Who Crashed Her Own Wake’, recounts the case of Melbourne woman Noela Rukundo, whose jealous husband organised a hit on her while she was visiting her family in Burundi. After informing Rukundo of the scheme, however, the hired killers decided to take the money and run, and, a few days later, she arrived home during her own funeral – to the shock of her husband.

The Twist is a snappy, engaging, visually distinctive program that uses a range of formal strategies to present crime stories in bite-size pieces without feeling like it has dived into someone’s dirty laundry, salacious affairs or sordid past.

Unlike other true-crime productions such as the Netflix series Making a Murderer or the podcast The Teacher’s Pet, which often involve drawn-out investigations and are heavy on drama and description, The Twist boasts a refreshing brevity. As its name also suggests, the series emphasises the surprising or the unexpected – another trait that sets it apart from its genre counterparts. Overall, The Twist is a snappy, engaging, visually distinctive program that uses a range of formal strategies to present crime stories in bite-size pieces without feeling like it has dived into someone’s dirty laundry, salacious affairs or sordid past.

A Dog Act: The Disappearance of Paddy Moriarty

https://iview.abc.net.au/show/dog-act-the-disappearance-of-paddy-moriarty

My first response to A Dog Act: The Disappearance of Paddy Moriarty was curious disbelief; I had trouble accepting that what I was seeing was a true story. More an extended piece of journalism, this four-part web series, reported by ABC journalist Anna Henderson, investigates what happened to seventy-year-old small-town local Paddy Moriarty and his kelpie, Kellie. Resembling the recent wave of podcasts examining unsolved crimes, the series attempts to determine whether Moriarty disappeared of his own accord or was met with foul play.

What A Dog Act is showing us is a part of Australia not often seen on screen, and … real people with deep resentments, even if the subjects of such tensions are rivalries around pies and stories of garden poisoning.

The remote and eccentric town of Larrimah, over 400 kilometres south-east of Darwin in the Northern Territory, provides the setting for this story. The combination of unusual townsfolk and the Pink Panther–themed local pub with live pet crocodile, along with the use of twangy music, initially makes it difficult to ascertain the series’ tone and seriousness. However, as it progresses, it becomes clear that what A Dog Act is showing us is a part of Australia not often seen on screen, and that these are real people with deep resentments, even if the subjects of such tensions are rivalries around pies and stories of garden poisoning. While the audience may feel slightly uncomfortable watching Henderson conduct her investigation and unearth these conflicts, what makes the series fascinating for the very same reason is the glimpse it offers into the implosion of this town with a population of ten.

Last Breath

https://www.youtube.com/girlsactgood

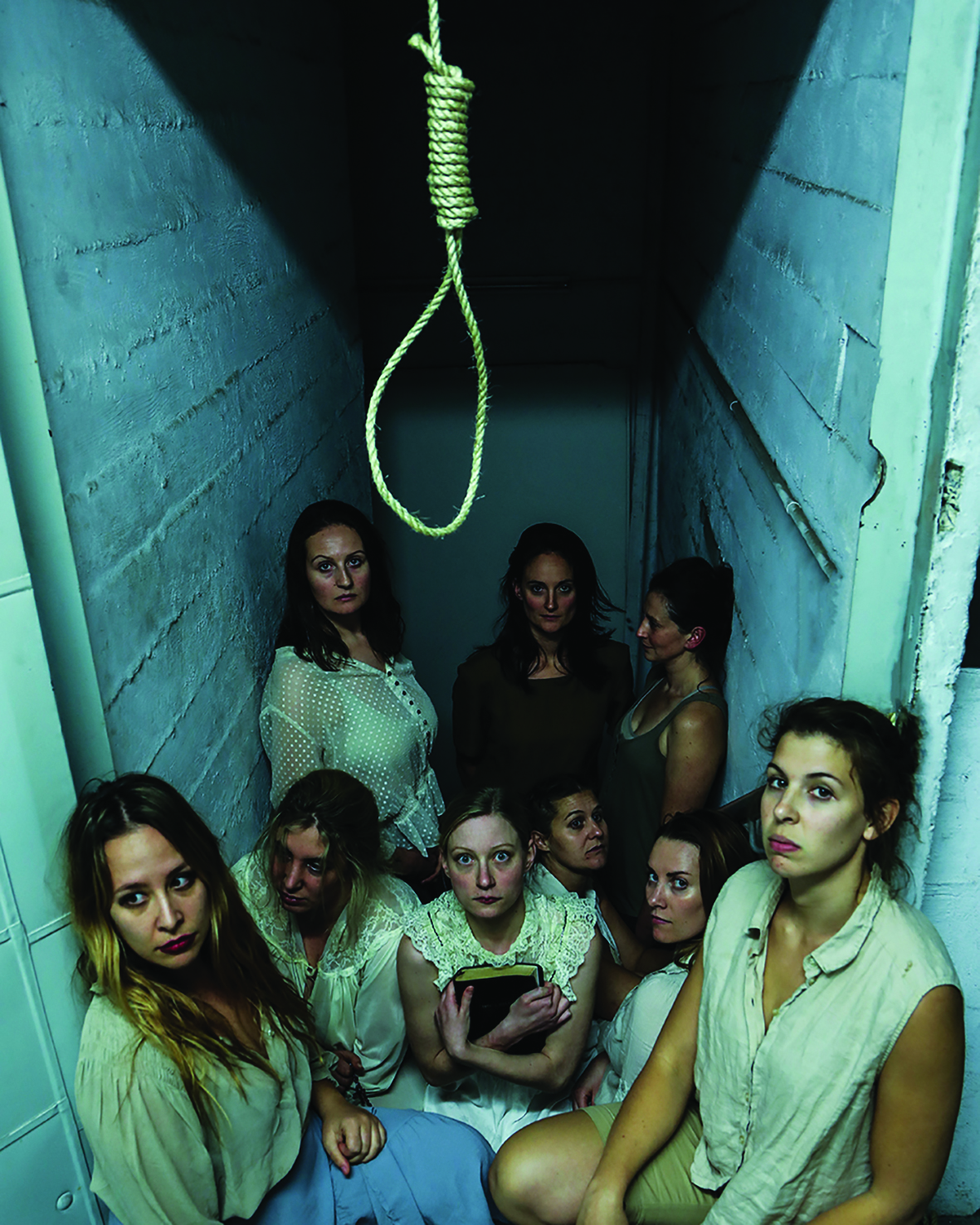

Continuing with the theme of true crime, nine-part series Last Breath depicts the lives of Australian women executed or imprisoned for life for murder. Produced by Girls Act Good – an all-female collective of actors, writers and filmmakers – in partnership with F Word Films, the show features monologues that recount the experiences of such notorious criminals as Martha Needle, who poisoned five family members, including her husband and three children, and was subsequently hanged in 1894; Jean Lee, the last woman to be executed in Australia, in 1951; and Katherine Knight, who brutally murdered and cooked her de facto partner in 2000 and planned to serve him to his children, and who was the first woman to be imprisoned for life without parole in the country.

Each monologue, written and performed by a member of the collective, is set either just before the execution or prior to its subject being sentenced to life in prison. The sparse setting for the episodes – only a chair is in frame – and the actors’ delivery to-camera make for unsettling viewing. What’s more, as the speeches are offered without context, the audience may find it difficult to appreciate the actors’ angry, frightened or unapologetic deliveries. Having said this, the pieces in Last Breath are striking for their more theatrical approach to storytelling compared to that seen in other web series, particularly in the genre of true crime.

*

The five web series I have discussed above comprise only a small selection of what was on offer at the 2019 Melbourne WebFest. While it is still worth pondering how the inherent gatekeeping of festival selection and/or external funding might constrain some risk-taking and experimentation, these titles do evidence the medium’s range of possibilities in terms of representation of diversity, aesthetics and storytelling.

Endnotes

| 1 | Aymar Jean Christian, Open TV: Innovation Beyond Hollywood and the Rise of Web Television, New York University Press, New York, 2018, p. 33. |

|---|---|

| 2 | A key example is Screen Australia’s Skip Ahead development program, run in partnership with Google; for more information, see ‘Skip Ahead’, Screen Australia website, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/television-and-online/production/special-initiatives/skip-ahead>, accessed 29 October 2019. |

| 3 | Whitney Monaghan, ‘Starting from … Now and the Web Series to Television Crossover: An Online Revolution?’, Media International Australia, vol. 164, no. 1, 2017, p. 83. |

| 4 | Stephanie Van Schilt, ‘How to Talk Australians and the Rise of Web Series’, Kill Your Darlings, 3 October 2014, <https://www.killyourdarlings.com.au/2014/10/how-talk-australians-rise-web-series/>, accessed 30 October 2019. |

| 5 | Founded in 2013, Melbourne WebFest is the fourth such festival in the world and one of the largest of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere. Last year’s four-day festival included workshops, screenings, networking opportunities and an iview-sponsored pitching competition. See <https://www.melbournewebfest.com>, accessed 30 October 2019. |

| 6 | ‘Pasifika’ is a term originating from New Zealand used to describe people from the greater Pacific region, including Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Niue, the Cook Islands, Tahiti and Hawaii; see ‘What Does Pasifika Mean?’, University of Otago website, <http://oil.otago.ac.nz/oil/module10/What-does-pasifika-mean-.html>, accessed 29 October 2019. |

| 7 | See The Coconet, <https://thecoconet.tv>, accessed 29 October 2019. |

| 8 | A fa‘afafine is a person who was assigned male at birth but lives as a woman – an identity that forms part of Samoan culture’s wider, non-Western conception of gender. For more, see Alan Weedon, ‘Fa‘afafine, Fakaleitī, Fakafifine – Understanding the Pacific’s Alternative Gender Expressions’, ABC News, 31 August 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-08-31/understanding-the-pacifics-alternative-gender-expressions/11438770>, accessed 29 October 2019. |

| 9 | Aymar Jean Christian, ‘Fandom as Industrial Response: Producing Identity in an Independent Web Series’, Transformative Works and Cultures, vol. 8, special issue 1, 2011, <https://journal.transformativeworks.org/index.php/twc/article/view/250/237>, accessed 29 October 2019. |

| 10 | Stayci Taylor, ‘“It’s the Wild West out There”: Can Web Series Destabilise Traditional Notions of Script Development?’, paper presented at the Australian Screen Production Education and Research Association annual conference, Adelaide, 15–17 July 2015, pp. 4–5, <http://aspera.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Taylor-2015_v2.pdf>, accessed 29 October 2019. |