Arcadia Heights isn’t really supposed to be anywhere in particular. Like Ramsay Street, Summer Bay and Wandin Valley before it, it doesn’t represent a real place, but more an idea of a place. Just as Neighbours plays out in a typical suburban street, Home and Away is set in a generic beachfront community and A Country Practice unfolds in an archetypal small country town, the ABC’s The Heights creates a broad canvas from a setting little explored by Australian soap operas to date: the typical inner-city neighbourhood.

It’s a bold and timely choice. Up until now, the Australian soap landscape has been largely, if not quite entirely, the province of the comfortable middle class. To be fair, Seven’s long-running A Country Practice had a large, rotating supporting cast of farmers and rural workers, but its focus remained resolutely on Wandin Valley’s professional class, specifically its doctors. Similarly, the same network’s Home and Away initially centred on the foster home run by the Fletcher family – but, in the three decades since the show’s debut, this attention to lower-socio-economic concerns has gradually been eroded.

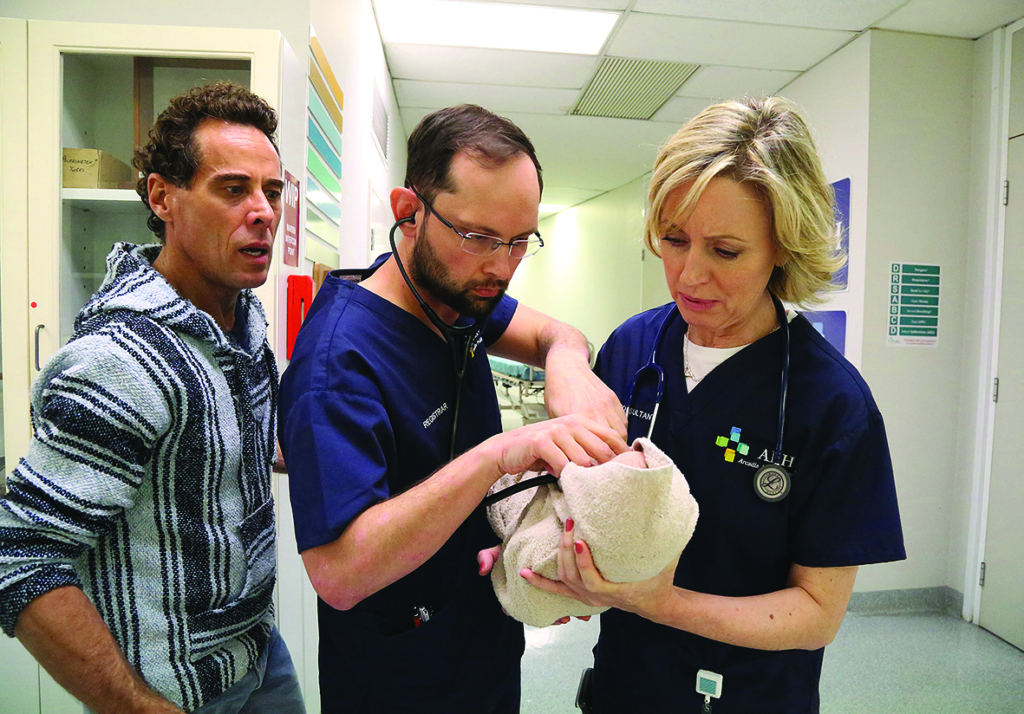

The Heights refutes such coyness; from the show’s marketing material alone, it would be reasonable for audiences to expect that the principal characters – residents of the Arcadia Towers community-housing complex that constitutes one of the series’ key loci – would be staunchly working-class. Indeed, we’re introduced to many of them in the first episode, when a false fire alarm rung at the towers brings the residents, including pensioned-off ex-cop Pav (Marcus Graham), into the street. But we’re soon whisked away from the grounds. After discovering an abandoned baby in one of the building’s flowerbeds, Pav takes the child to the local hospital, which connects him with emergency-department doctor and single mother Claudia (Roz Hammond), who lives in a modern townhouse in the vicinity of the towers; her daughter, Sabine (Bridie McKim), who has cerebral palsy, attends the local high school alongside Pav’s son, Mich (Calen Tassone). Mich’s mother, Leonie (Shari Sebbens) – an Indigenous lawyer living in a refurbished warehouse in the towers’ neighbourhood – is struggling to balance her job, her family and caring for her father, who is struggling with the onset of dementia.

Like any soap worth its salt, The Heights sets up a complex web of relationships and rivalries – too complex, really, to be outlined in any great detail here – but ‘diversity’ is the watchword among the series’ extended ensemble. Outside of the central Pav/Claudia/Leonie axis, there’s gay Vietnamese-Australian university student Sully (Koa Nuen), whose well-meaning mother, Iris (Carina Hoang), meddles in his love life when she’s not running the local deli. Sully is attracted to his best friend, Iranian refugee Ash (Phoenix Raei), who in turn is struggling with being treated like an exotic novelty by his wealthy, white friends. Ash’s younger brother, Kam (Yazeed Daher), is a nascent entrepreneur determined to work his way out of poverty, but finds studying in a crowded, multi-generational household difficult – he gets an unexpected ally in fellow immigrant businessperson Iris. And on, and on.

Throughout these tangled narrative and relationship dynamics, key themes recur again and again: identity, community, self-determination. Often, these are presented in opposition to one another. Sully wants to be a teacher, in spite of his mother’s expectation that he aspire to a loftier profession. Sabine seeks a sense of self outside of and separate to her identity as a person with a disability. Pav, the most ‘conventional’ of the series’ protagonists (he’s straight, white, male and middle-aged), wants a romantic relationship with Claudia, but must contend with the baggage of his old life and his current, rather straitened circumstances. Characters frequently struggle to be who they want to be, or else feel they are constrained by societal or cultural forces.

While it has been celebrated as a working-class drama, the show is careful not to be too working-class … Our true protagonists prove to be individuals with no small amount of comparative power and wealth.

What emerges as the series’ other big theme is gentrification; as Renee (Saskia Hampele), who is married to tradesman Mark (Dan Paris), remarks to Leonie in an early episode, ‘Our house prices would go up 20 percent if the towers weren’t there.’ It’s through the local pub, The Railway, that the show develops this theme most acutely. After the death of her father, hardworking, put-upon proprietor Hazel (Fiona Press) plans to sell the establishment quickly and move on, but finds she must share her inheritance with her estranged son, Ryan (Mitchell Bourke), and drug-dependent daughter, Shannon (Briallen Clarke) – the mother of the abandoned baby of the first episode. A raft of hitherto-unknown debts means they must work together to run the establishment, with Ryan, who has shed his working-class roots and adopted a hipster aesthetic and attitude, planning significant changes. These draw the consternation of one of the locals, Watto (Noel O’Neill), an Irish heavy drinker who soon becomes a source of comic relief.

And therein lies the problem with The Heights. While it has been celebrated as a working-class drama,[1]See, for example, Sarah Attfield, ‘The Heights – at Last, a Credible Australian Working-class Soap’, The Conversation, 6 March 2019, <https://theconversation.com/the-heights-at-last-a-credible-australian-working-class-soap-112961>, accessed 17 May 2019. the show is careful not to be too working-class – and certainly points its camera away from the poverty-racked characters who must, by inference if not appearance, also dwell in Arcadia Towers. There are exceptions – one episode opens with a few unnamed homeless people idly watching some of the principal characters attend a tai chi class in the nearby park – but these moments are fleeting. Our true protagonists prove to be individuals with no small amount of comparative power and wealth: a former police officer, a lawyer, a doctor and no fewer than six small-business owners. More importantly, these characters have an implied degree of social mobility. Pav, who deals a little weed to support himself, may rail against the barriers he sees to a relationship with Claudia, but, in dramatic terms, his circumstances present no real impediment to his goal. This social mobility is especially manifested in the series’ younger characters, all of whom have access to what we might think of as financial and political ‘exit ramps’: employment, education, opportunities.

Those characters who might actually spend their lives at this socio-economic level are implicitly suffering from self-inflicted woes: Mark has a gambling problem, which has financially crippled his family; Shannon has a fairly undefined substance-abuse issue; and Watto struggles with alcoholism. The systemic barriers to upward social and economic momentum remain unaddressed: we never see a character struggle to deal with the coalface of Centrelink bureaucracy, or underfunded social programs. Surely, there’s drama to be mined from the controversial ‘robodebt’ program,[2]See Heidi Pett & Colin Cosier, ‘We’re All Talking About the Centrelink Debt Controversy, but What Is “Robodebt” Anyway?’, ABC News, 3 March 2017, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-03/centrelink-debt-controversy-what-is-robodebt/8317764>, accessed 27 May 2019. to pinpoint just one widely known and reviled issue affecting the less-affluent? But not only are these issues not dramatised – they’re not even alluded to; characters never speak about such things, let alone experience them.

Watto, although a minor character, is particularly problematic, in that he is an archetype that is largely unchanged from the days of Cookie (Syd Heylen) and Bob (Gordon Piper) in A Country Practice: the comic buffoon. In the context of The Heights – with its ostensible social-justice agenda[3]As co-creator Que Minh Luu put it prior to the series’ release, ‘Our goal wasn’t just to do diversity, but to do it well. The secret sauce to that, of course, is to always interrogate representation at every stage’; see Luu, ‘Your New Neighbours: Why Australia’s Latest Soap The Heights Tells a Different Story’, The Guardian, 20 February 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/feb/20/your-new-neighbours-why-australias-latest-soap-the-heights-tells-a-different-story>, accessed 17 May 2019. – such a characterisation simply doesn’t fly. Indeed, by positioning Watto as a figure of fun, The Heights is participating in the same mockery perpetuated by the likes of earlier ABC series Upper Middle Bogan and SBS’s Housos, which mine the experiences of disadvantaged characters for humour but turn away from more robust critique. In the universe of The Heights, there appears to be a level of poverty and functionality below which derision is warranted. Those with the opportunity to improve themselves are portrayed as laudable; those who are ‘stuck’ are consigned to being comedy fodder.

It’s a rare discordant note in an otherwise well-constructed work. Co-creator Que Minh Luu has been open about having spent part of her childhood in public housing,[4]ibid. so we can safely say that she is, to some degree, writing from her own experience. But, while The Heights demonstrates a great deal of empathy for its ethnically and sexually diverse cast, it seems to have a blind spot when it comes to certain societal hierarchies. At the very least, our protagonists are unarguably positioned on one side of some kind of socio-economic line – one that seemingly associates aspiration and mobility with screen-worthiness – and anyone on the other side, like Watto or the unnamed homeless contingent, remain strongly Othered.

While The Heights demonstrates a great deal of empathy for its ethnically and sexually diverse cast, it seems to have a blind spot when it comes to certain societal hierarchies … the show feels like a middle-class person’s idea of what economically disadvantaged life must be like.

This inevitably gives rise to a whiff of inauthenticity: the show feels like a middle-class person’s idea of what economically disadvantaged life must be like. This aura of unreality is not helped by the series’ fairly non-specific setting. The Heights is filmed in Western Australia, mostly in and around the inner-city enclave of East Perth;[5]‘New Heights: ABC Drama Series Starts Production in East Perth’, WA Today, 1 June 2018, <https://www.watoday.com.au/national/western-australia/new-heights-abc-drama-series-starts-production-in-east-perth-20180601-p4ziwn.html>, accessed 17 May 2019. however, as Arcadia Heights is supposed to be a shorthand sketch of any possible gentrifying urban neighbourhood, references to actual places, customs, businesses and so on are almost universally avoided. This approach may suffice for the sun-bleached, largely apolitical dramas of Summer Bay and its ilk, but the grit that The Heights is clearly reaching for demands specificity. It is not enough to posit a mythical working-class neighbourhood; the themes and tone adopted by the series would have been better served by an actual place – or, at least, a place that feels firmly situated in the real world. As it stands, the most concrete indicator that Arcadia Heights is located within the actual metropolitan area of Perth comes when Uncle Max (Kelton Pell), an Indigenous elder, performs a Welcome to Country ceremony and specifically invokes the Nyungar people of the Whadjuk nation, of whom he is a member.

In terms of visual style, The Heights sets itself apart from the soapy pack by employing devices drawn from contemporary prestige dramas. Under the direction of James Bogle, Andrew Prowse, Renée Webster and Darlene Johnson, the series employs an unusual amount of handheld camera work for a soap, and this, coupled with extensive use of location shooting on the streets of Perth, lends the series a palpable feeling of immediacy and tactility. The overall effect is somewhat documentary-like, while still existing within the aesthetic framework of the Australian prime-time soap. Scene transitions are tight and abrupt, moving the multiple plotlines in any given episode along at a rapid clip. We’re rarely left waiting for the narrative to come to the boil; The Heights roils along nicely, constantly deploying conflict, catharsis and resolution at the micro level while also tending to its macro themes of class and identity. It is a superbly constructed show.

Which is why its more obvious faults are forgivable. The speed and scale of The Heights’ storytelling means that its shortcomings – not-always-polished economic and class representation, non-specificity of setting – can be dealt with easily, as we quickly move on to the next plot point or portrayal. More importantly, the series represents an intriguing and welcome possible future idiom for Australian television drama, one in which diversity and visibility are baked into the dramatic fabric of the form. In order to do so, shows like The Heights need to be more mindful of their own potential shortcomings, and ensure that, in enacting what Luu has called ‘an expression of an unconscious desire to be visible in a world that wouldn’t acknowledge [her] existence’,[6]Luu, op. cit. they’re not still reinforcing classist stereotypes. It’s not enough to move the barriers to representation; they must be dismantled. Overall, though, The Heights remains a compelling watch, and its commitment to diversity and visibility offers up opportunities for drama and politico-cultural exploration that no other recent series on Australian television addresses.

https://www.abc.net.au/tv/programs/heights/

Endnotes

| 1 | See, for example, Sarah Attfield, ‘The Heights – at Last, a Credible Australian Working-class Soap’, The Conversation, 6 March 2019, <https://theconversation.com/the-heights-at-last-a-credible-australian-working-class-soap-112961>, accessed 17 May 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See Heidi Pett & Colin Cosier, ‘We’re All Talking About the Centrelink Debt Controversy, but What Is “Robodebt” Anyway?’, ABC News, 3 March 2017, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-03-03/centrelink-debt-controversy-what-is-robodebt/8317764>, accessed 27 May 2019. |

| 3 | As co-creator Que Minh Luu put it prior to the series’ release, ‘Our goal wasn’t just to do diversity, but to do it well. The secret sauce to that, of course, is to always interrogate representation at every stage’; see Luu, ‘Your New Neighbours: Why Australia’s Latest Soap The Heights Tells a Different Story’, The Guardian, 20 February 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/feb/20/your-new-neighbours-why-australias-latest-soap-the-heights-tells-a-different-story>, accessed 17 May 2019. |

| 4 | ibid. |

| 5 | ‘New Heights: ABC Drama Series Starts Production in East Perth’, WA Today, 1 June 2018, <https://www.watoday.com.au/national/western-australia/new-heights-abc-drama-series-starts-production-in-east-perth-20180601-p4ziwn.html>, accessed 17 May 2019. |

| 6 | Luu, op. cit. |