Australia’s cultural sector is on life support – but admirable attempts to take events online have proliferated, to varying degrees of success. Sadly, a combination of readily available machinery and the misguided promise that the digital space offers to non-native organisations has meant that these are regularly bland and sometimes awkward affairs – and very rarely a match for the infinite, actually edited content already available through streaming services. It’s rare to see anyone doing anything interesting with the medium into which they have been thrust (with notable exceptions being the Art Gallery of New South Wales’ ‘Together in Art’ online labyrinth and Prototype’s video-art ‘care packages’[1]See Kim Munro, ‘“Rummaging Through the Rubble”: Creative Constraints in Prototype’s Rapid-response Care Package’, Metro, no. 206, 2020, pp. 70–5.). Static Vision, a formerly Sydney-based film collective formed in 2018 and run by 28-year-olds Felix Hubble and Conor Bateman, has, however, nimbly stepped into this sparse canyon by broadcasting a series of interactive livestreams that have collectively ended up a much bigger and more ambitious project than their offline output.

Before COVID-19 hit, Static Vision ran monthly screenings focusing on new, formally exciting cinema that was not getting a Sydney release. Often, these films would come to the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF) but be bypassed by the more mainstream Sydney Film Festival (SFF). Several sold-out screenings of Bi Gan’s astonishing Long Day’s Journey into Night (2018) and the Australian premiere of RaMell Ross’ Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018) – the latter organised prior to its Oscar Best Documentary nomination – are good examples of the collective’s programming instincts. These monthly screenings formed the backbone of a schedule that would otherwise be mixed with obscure late-night horror doubles and occasional collaborations with other Sydney critics and programmers.

Bateman and Hubble moved to Melbourne just before the pandemic changed everything. On 16 March 2020, the first lockdowns hit Australia. Within two weeks, the first Static Vision livestream – promoted as ‘a marathon six-hour live-stream of specially-curated feature films and shorts […] accompanied by a host of e-chats, Q&As, and interviews’ and presented in a ‘unique online screening room’[2]‘Lockdown: An Interactive Livestream’, Facebook Event, 27 March 2020, <https://www.facebook.com/events/httpscytuberstaticvisionau/lockdown-an-interactive-livestream/2895996303780525/>, accessed 2 November 2020. – was broadcast from the organisers’ separate living rooms.

This wayward first stream included the Australian premiere of the bewitching VHS found-footage poem Stand By for Tape Back-up (Ross Sutherland, 2015), along with a rich basket of shorts and minimalist marvel The Strange Little Cat (Raymond Zürcher, 2013), which had previously only screened in Australia at the Audi Festival of German Films in 2014 and the excellent (but relatively low-profile) Queensland Film Festival the following year. This first stream was the unintended beginning of a weekly screening event that endured as the pandemic continued to mess with Australian social lives.

At the time of writing, thirty-two weekly livestreams have been broadcast via the Static Vision website. The majority of sessions have been around five or six hours long, each sending a surprisingly wild array of screen content into the homes of a growing cohort of followers, most of whom were in Melbourne and, from the beginning of July until late October, coping with the city’s alienating second lockdown. An impressive number of films shown in this online cinema have been accompanied by live, extended filmmaker interviews. So far, that list has included Paul Schrader, Cecelia Condit, Guy Maddin and Amanda Kramer, among many others. The content is arranged thematically each week and swings from elegant selections of experimental shorts to video nasties screened on VHS (in full, with piracy warnings and trailers).

Guest programmers are a regular feature. Well-known and beloved Australian critics Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Richard Kuipers have each taken the reigns so far; multidisciplinary artist and musician Darren Sylvester curated an evening of music videos that have influenced his twenty-year career; and Kai Perrignon of Melbourne’s Trash Night and Ingrid Dieckmann of Marrickville’s Pink Flamingo Cinema, who both ‘fly the flag of outsider art, trash and sleaze’,[3]‘2 Trash 2 Night: Pink Flamingo x Trash Night Takeover’, Facebook Event, 15 May 2020, <https://www.facebook.com/events/pink-flamingo-cinema/2-trash-2-night-pink-flamingo-x-trash-night-takeover/552049855741963/>, accessed 2 November 2020. have taken over enough times that they are now key members of the collective.

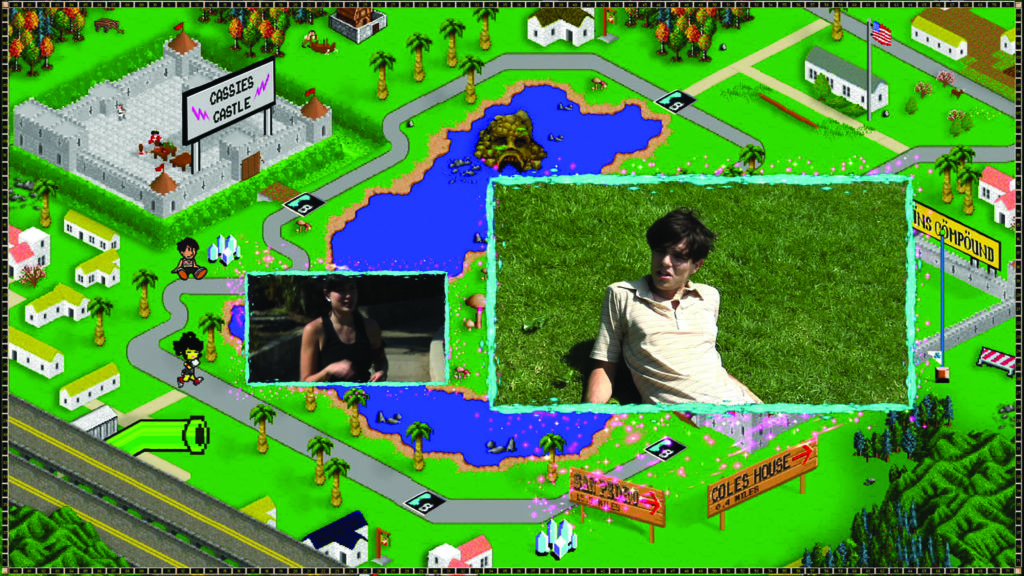

In July, Bateman and Hubble also curated an online version of their cleverly programmed Hyperlinks Film Festival, Hyperlinks URL,[4]See Hyperlinks URL festival website, <https://hyperlinks.online/>, accessed 2 November 2020. which provided a full weekend of screenings of contemporary screen works. This was broadcast in the same online screening room, forming a bumper edition of their already-chunky weekly offerings.

Two things make this collective worthy of special attention. The first is that, unlike any other online screening service, including established film festivals, the lockdown livestreams and Hyperlinks URL festival are all broadcast from the one location in real time. The second, perhaps more significant, feature is that the collective has managed to scoop out a space in which the old but stubborn dichotomies of high and low art in film culture are deliberately and joyfully obliterated.

An online broadcast model

Bateman and Hubble tell me that they were driven by a desire to build the sense of place and community usually found in offline film festivals and curated screenings into their own project. The pair were well aware that anyone can get their hands on a hard drive full of good cinema if they try hard enough – but also that that doesn’t make life in lockdown any less lonely, and that it doesn’t replace the longed-for experience of watching something new and great with a few hundred others in a darkened movie theatre, or taking that same film apart over a beer after the film.

Viewers who ‘arrive’ at Static Vision’s online screening room at the designated time will experience this content in the same place as between forty and 200 other people, depending on the night. There’s no clicking on links to go outside the space, and no option to purchase a film to maybe watch another time. One simply loads up the website on their smart TV, laptop or phone, choosing the ‘chat’ option if they want to be in contact with the other attendees during the screening.

The broadcast model is so simple and potent that it’s surprising that no other festivals have made the same decision. How many MIFF or SFF films were bought but unwatched this year? On Twitter, the #miff2020 hashtag was active, but only had a fraction of the vigour of its predecessors, which normally dominate the Australian film community’s feeds over the course of the two-week festival. A curated and shared time and place are essential elements of the electric experience of these events. Instead of creating scarcity by arbitrarily limiting ticket capacity, the single-timeslot broadcast model imbued Static Vision’s lockdown screenings with a significance and rarity that also felt generous: a literal special occasion. The feeling was not unlike that of watching the marvellous Eat Carpet, the late-night SBS series that ran from 1989 to 2005 and showcased (usually experimental) amateur and student films from all over the world. Staying up late alone as our parents slept, our faces centimetres from the TV screen as the most wondrous collection of moving-image oddities tumbled out, we had the opportunity to sense that we were accessing secrets, discovering new things and entering a community of other late-night weirdos – one that was imagined but sincerely felt.

Making art cinema more approachable

For many a suburban teenager, Eat Carpet was the first taste of a cinema that could be something outside the shiny, tight things Hollywood or Australian television put into the world. Static Vision’s founders are seeking to do something similar. They want to reach young people (roughly eighteen to thirty years of age) who would not otherwise experience formally adventurous work, as it is usually locked up in institutions and cultural frameworks that work hard to connote a level of seriousness and sophistication. In conversation for this piece, Hubble expands on this:

There’s a lot of effort from institutional powers to pick the right [films] and present them in super-academic contexts. But there isn’t a lot of thought that goes into the aesthetics of what they’re doing – the feel, the vibe of the event just isn’t there.

Bateman concurs:

We know a lot of people in our age demographic do not go to these things, or they feel alienated by the way certain retrospectives are marketed and simply aren’t interested. But we thought, ‘We can get them interested in, like, [German director] Angela Schanelec; we can get them interested in Long Day’s Journey into Night – we just need to spin it the right way.’

In aiming for a younger audience, the Static Vision founders’ anti-stuffy aesthetic has resulted in something genuinely new for everyone.

This democratic approach to place making, to the tearing down of make-believe barriers to works of Cultural Importance, is a political one, and fits nicely into modernist playwright Bertolt Brecht’s rethinking of popular culture in his 1938 essay ‘Popularity and Realism’:

Our concept of what is popular refers to a people who not only play a full part in historical development but actively usurp it, force its pace, determine its direction. We have a people in mind who make history, change the world and themselves. We have in mind a fighting people and therefore an aggressive concept of what is popular.[5]Bertolt Brecht, ‘Popularity and Realism’, trans. Stuart Hood, in Francis Frascina & Charles Harrison (eds), Modern Art and Modernism, Harper & Row Ltd, London, 1982, p. 228. Emphasis in original.

This view of popular culture describes Static Vision’s interventionist programming and potential audience. It also conjures images of young people battling through the desperate year that was 2020.

In the course of my discussions with Bateman and Hubble, a collection of manifesto-esque rules for their online output bubbled to the surface of their enthusiastic chatter. Together, these mandate an accessibility built on a robust disregard for classical notions of class and taste:

· Make it free

· Keep it casual

· Screen films that have never screened locally, at least in Melbourne

· No video on demand – this is a shared experience

· No commercial sponsors, ever

· If we like it and it’s hard to see elsewhere, we screen it

· Trust us – we know what we’re doing.

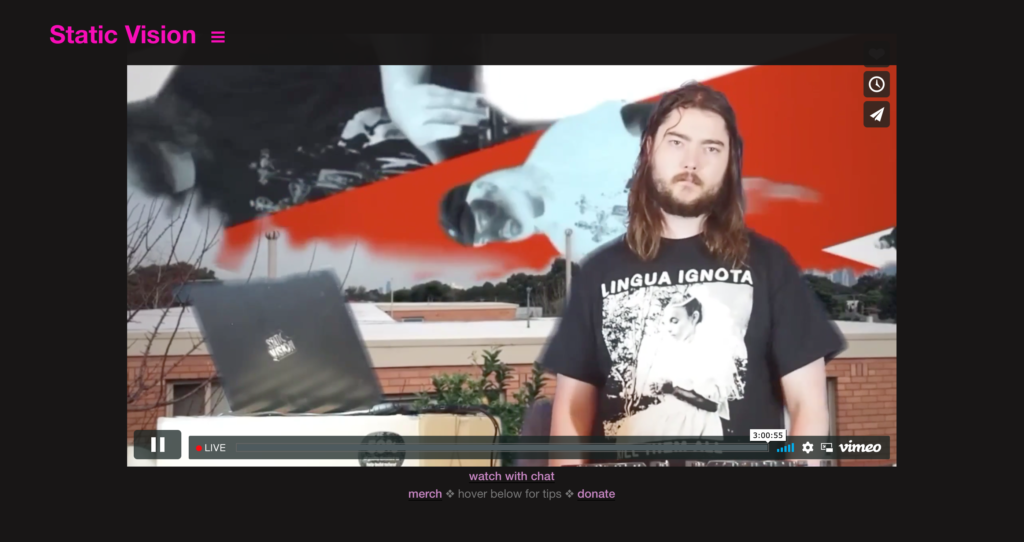

The smart-slacker aesthetic of Static Vision’s promotion and on-screen activity between films is where ideas of exclusivity and authority that usually surround art cinema are played with most freely. Despite the combined talents of the collective, this is not a slick operation. Many of the livestreams have started with Bateman and Hubble on screen asking their viewers to let them know in the chat if they are even live. The two sit at their desks in their separate sharehouses, unruly backgrounds freely visible, chatting away while they eat takeaway, drink beer and ad-lib. They often make programming decisions live and are open with their viewers if they haven’t yet booked anything for the next week. Often, the between-film conversation goes on way too long, with all kinds of segues and in-jokes. They find each other very amusing. This could all be perceived as self-indulgent if not for the relaxed and warm delivery that conveys, more than anything, that they don’t mind at all if you tune out. This idea is baked into the weekly format, and is also why shorts are a major component of their programming. As Hubble explains:

Online operates a bit more like a gallery space in which people dip in and out, and pay attention to what they want to pay attention to […] People were trying to do the things that they would do offline, and that just doesn’t make sense. [Online] is a completely different format, completely different to the way we interact with a cinema space.

Hyperlinks URL carried the same ethos and dedication to mess. The program was made up of contemporary, formally exciting films – notably, Chen Zhou’s gorgeously dissociative Life Imitation (2019) and Adam Khalil and Bayley Sweitzer’s fantastic Empty Metal (2018) – most of which were Australian premieres. A retrospective of Lawrence Lek’s unsettling, dreamy and usually gallery-based video work topped things off. All of this was held together by a neon-addled, laissez-faire aesthetic, with matching hosts. For half of the festival weekend, Hubble wore a terry towelling bathrobe. DJ sets accompanied by ugly-beautiful-ridiculous visuals added a party feel. Gone were the hierarchical and heavily guarded hallmarks of cultural capital that usually both explicitly and implicitly accompany curation of this kind. This roughing up and repackaging of high-art cinema represents a productive clash between pop and avant-garde aesthetics that is, in the festival space at least, rarely achieved without compromise or commercialisation.

The radical and immeasurably influential filmmakers and theorists who politicised the aesthetic innovations of the French New Wave argued that cultural politics needed to be enacted on two fronts, subject and form, but many also mourned the fact that their work did not reach outside the intimate circles of the avant-garde. Godard, for example, included this statement in his section of the epic portmanteau film Far from Vietnam (various directors, 1967):

I am cut off from the working class, but my struggle against American movies is related; yet workers don’t come to see my films. It is a split like our split with Vietnam.

This ‘split’ requires constant negotiation as boundaries of class and taste adapt with each generation’s aesthetic intervention: the ceaseless dance of cooption and resistance.

Cinema, like language, is in a perpetual state of evolution. This process is dialectically charged and chaotically cyclical. Drawing attention to the filmmaking or storytelling process through refracting, foregrounding or completely obliterating classically understood norms of cinematic realism opens up new ways of making meaning: political, metaphysical or otherwise. However, the further away from contemporary dominant (mainstream) modes of signification a work gets, the higher the risk of incomprehension, and the more people the work has the potential to alienate. The environment in which such works are shown matters.

Bateman and Hubble believe that their decision to refuse both commercial sponsorship and payment for their labour makes their unapologetic programming and its democratic, dishevelled delivery possible. This may be true. After all, they operate outside a system that would make their output transactional; Static Vision’s revenue or its members’ livelihoods are not threatened by the artistic choices they might make. Conversely, that also means that the immense amount of labour put into the project is not factored into the project budget, and therefore could be rendered invisible, like so much other work done in the cultural sector in Australia. This is more of a caution than a criticism. Keeping record of hours donated ‘in kind’ on grant applications and the like is a simple way of making state and local governments aware of the work being done in what are now dubbed creative industries. So far, the collective has broken even in terms of outgoings. Static Vision’s online output is not ticketed, but donations are welcome. Their aim is to avoid losing money rather than making it.

It would be nice – but perhaps naive – to think that it could be possible to earn a living putting something like this into the world. New income models like Patreon go some ways towards answering this question. In the meantime, however, the fruits of this elaborate but clearly enjoyable hobby are a generous gift to viewers who, most likely, have had a very tough year.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Kim Munro, ‘“Rummaging Through the Rubble”: Creative Constraints in Prototype’s Rapid-response Care Package’, Metro, no. 206, 2020, pp. 70–5. |

|---|---|

| 2 | ‘Lockdown: An Interactive Livestream’, Facebook Event, 27 March 2020, <https://www.facebook.com/events/httpscytuberstaticvisionau/lockdown-an-interactive-livestream/2895996303780525/>, accessed 2 November 2020. |

| 3 | ‘2 Trash 2 Night: Pink Flamingo x Trash Night Takeover’, Facebook Event, 15 May 2020, <https://www.facebook.com/events/pink-flamingo-cinema/2-trash-2-night-pink-flamingo-x-trash-night-takeover/552049855741963/>, accessed 2 November 2020. |

| 4 | See Hyperlinks URL festival website, <https://hyperlinks.online/>, accessed 2 November 2020. |

| 5 | Bertolt Brecht, ‘Popularity and Realism’, trans. Stuart Hood, in Francis Frascina & Charles Harrison (eds), Modern Art and Modernism, Harper & Row Ltd, London, 1982, p. 228. Emphasis in original. |