It’s a tale as old as time, a song as old as rhyme: a lonely, socially outcast seventeen-year-old girl in rural Japan, scarred from the tragic childhood death of her mother, enters into a biometrically enabled metaverse via the avatar of a pop singer, becomes a global viral phenomenon, crosses paths with a dark and troubled ultraviolent martial-arts fighter, falls foul of online morality police, and must sing a climactic power ballad to save her reputation as well as two kids from child abuse – all while navigating the IRL[1]Internet shorthand for ‘in real life’. dramas (cliques, cattiness, crushes, rivals) of your average high-schooler.

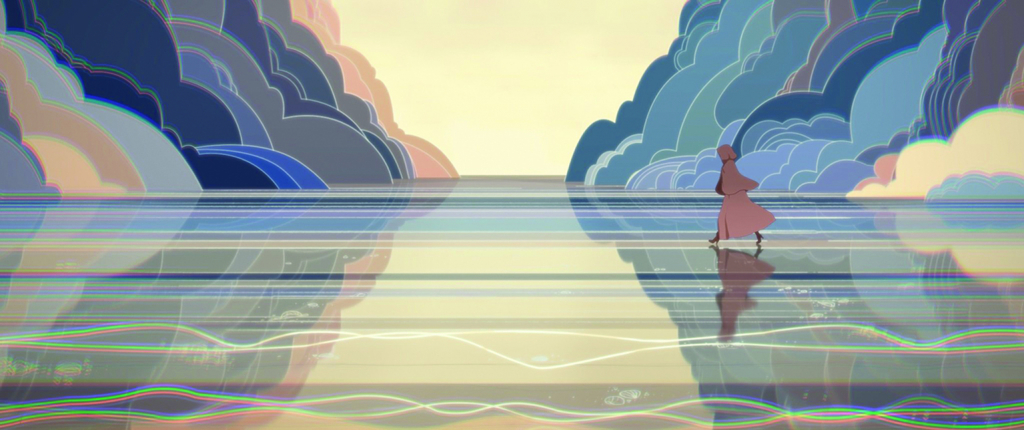

Belle (2021), the latest film from anime auteur Mamoru Hosoda, is filled with the symbolic predilections that litter his filmography: young protagonists on journeys of self-discovery; shifts between real-life and fantastical otherworldly/online realms; imagery such as towering cloud formations, anthropomorphised animals, whales swimming through space and artful passing-of-time montages. It also offers a continuation of the ideas explored in his previous films: The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006), which contrasts high school boy/girl dramas with fantastical time-travel alternate realities; Summer Wars (2009), which presents online virtual-realm events as having huge real-world repercussions; and The Boy and the Beast (2015), which descends into an underworld of yōkai, or supernatural human/animal hybrids. Belle opens in the exact same fashion as Summer Wars, introducing and explaining its fictional virtual realm (Hosoda has acknowledged this as a deliberate reference to the earlier film[2]Ard Vijn, ‘Belle Interview: Director Hosoda Mamoru Provides Hope for the Future’, ScreenAnarchy, 12 January 2022, <https://screenanarchy.com/2022/01/belle-interview-director-hosoda-mamoru-provides-hope.html>, accessed 23 February 2022.); and it ends with the same tableau as The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, with our adolescent heroine gazing up at a giant mass of clouds on the horizon symbolising a wide-open future.

Yet Belle is also an unapologetic homage to the 1991 Disney film Beauty and the Beast (Gary Trousdale & Kirk Wise), which holds a mythical place in Hosoda’s life. Starting out with an entry-level role at Toei Animation, he found the work sufficiently ‘difficult and demanding’ to make him doubt his dreams. But then he saw Beauty and the Beast, and loved it so much he invested in an expensive VHS box set that included behind-the-scenes and work-in-progress features.[3]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Nobuhiro Hosoki, ‘An Exclusive Interview with Director Mamoru Hosoda on Belle’, CinemaDailyUS, 17 January 2022, <https://cinemadailyus.com/interviews/an-exclusive-interview-with-director-mamoru-hosoda-on-belle/>, accessed 23 February 2022. It made such a mark on him that Hosoda has been referencing the film for years: Wolf Children (2012) features a romance between a woman and a wolf-man, while The Boy and the Beast refashions the tale into a son/father drama. ‘I’ve wanted to make my interpretation of Beauty and the Beast for 30 years now,’ Hosoda admits.[4]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Andrew Webster, ‘Belle Director Mamoru Hosoda on Creating a Metaverse Fairy Tale’, The Verge, 11 January 2022, <https://www.theverge.com/22866629/belle-mamoru-hosoda-director-interview>, accessed 23 February 2022.

In translating this French folktale to the technologically saturated twenty-first century, Hosoda says he ‘wanted to think really hard’ about what it means to be a contemporary ‘beauty’ or ‘to become a beast’.[5]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Gregory Ellwood, ‘Mamoru Hosoda on Creating a Virtual Beauty and the Beast for Belle [Interview]’, The Playlist, 17 January 2022, <https://theplaylist.net/mamoru-hosoda-belle-interview-20220117/>, accessed 23 February 2022. Suzu (voiced, in both speech and song, by Kaho Nakamura), is a wallflower who sits on the margins of her high school’s social hierarchy. She lives with her father, but routinely ignores his tentative attempts to connect. Having acquired an early love for singing and playing music, she now refuses to do either. She’s haunted by the death of her mother, who drowned rescuing a stranded girl in flooding rains.

The potential of our increasingly digital world, both positive and negative, sits at the centre of Belle’s story; the director says that his intention was to offer his young viewers an exemplar of online hope.

In the virtual world of U, Suzu finds her voice again, both musically and personally. It’s there, as Belle, that she crosses paths with this movie’s beast. In final-act revelations, we discover that Kei (Takeru Satoh), the surly teenage goth behind the avatar of the beastly fighter Dragon, is also reeling from his mother’s death and lives in fear of his abusive father (Ken Ishiguro). The online violence Kei administers as Dragon is the product of trauma, and a disturbing visual flourish shows his offline bruises blossoming on his online avatar’s body. In the grand tradition of girls hoping to rehabilitate wayward bad boys, Belle pens Dragon a tender ode: ‘You want to be left alone / or that’s what you’ll say / as you push me away,’ she sings, ‘but the truth is you don’t want me to look / to see what’s in your heart / anger, fear, sorrow.’ As the song plays, the two dance, Dragon wearing a suit as the pair rise up into the stars – Hosoda staging a Beauty and the Beast homage with hints of La La Land (Damien Chazelle, 2016).

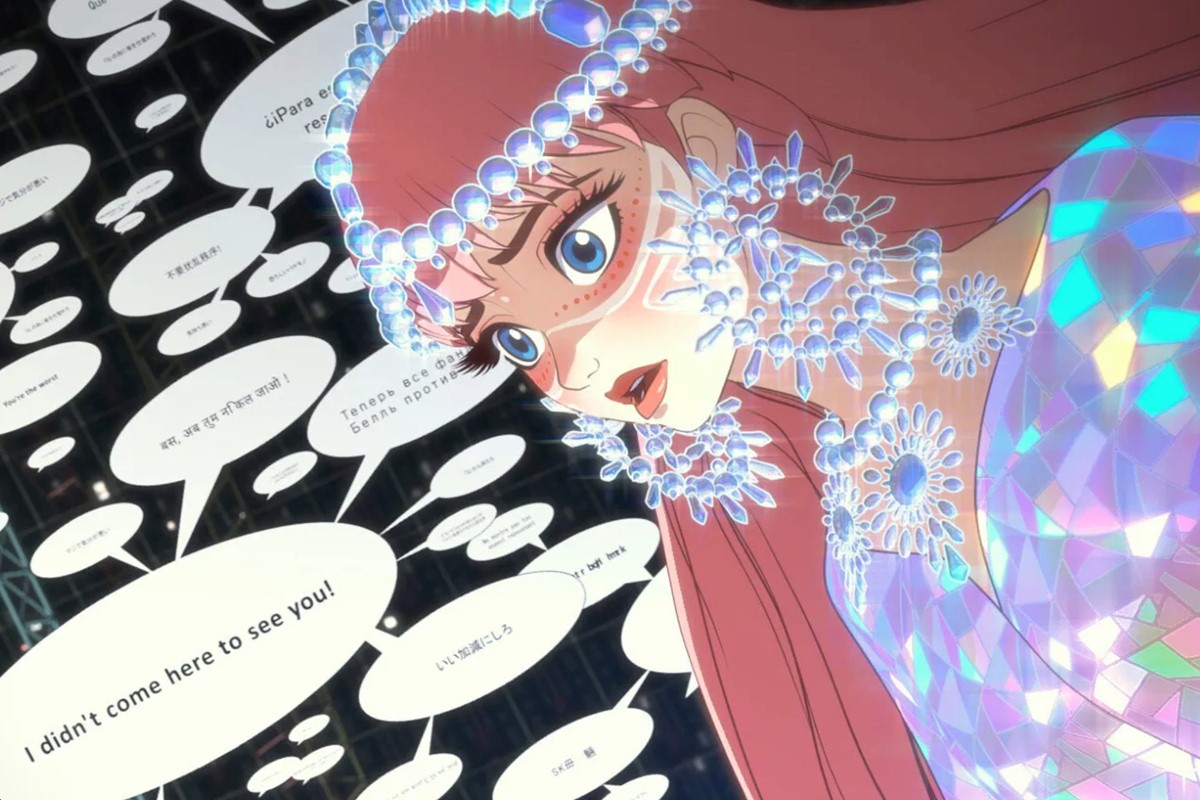

Dragon’s castle inhabits a storybook realm of its own discrete animation style, presided over by Cartoon Saloon, the Irish animation house behind folkloric features like The Secret of Kells (Tomm Moore & Nora Twomey, 2009), Song of the Sea (Moore, 2014) and Wolfwalkers (Moore & Ross Stewart, 2020). They form part of an eclectic international cast of contributors giving different elements of Belle distinct visual approaches. The design of U’s teeming data-metropolis was the work of London-based conceptual digital architect Eric Wong, whom Hosoda contacted after discovering his work on the internet;[6]Toussaint Egan, ‘Belle Is the Virtual World Anime that Mamoru Hosoda Always Wanted to Make’, Polygon, 12 January 2022, <https://www.polygon.com/22870380/belle-mamoru-hosoda-interview>, accessed 24 February 2022. while Jin Kim – a Disney animator known for Frozen (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee, 2013) – designed Belle, a striking figure with a flowing mane and freckles worn like face paint.[7]ibid. The real world, where Suzu lives a lonely life of long bus rides, is rendered in traditional hand-drawn 2D animation; whereas the online realm of U, a digital hive populated by over 5 billion global users, is portrayed in 3D computer animation.

‘I wanted designers with different values from all around the world to be involved in creating this film,’ Hosoda says. ‘The story is set in a more globalized future [… and] there are just different forms of expression that are becoming more recognized, so we wanted to honor that by drawing from different influences and different viewpoints.’[8]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Rafael Motamayor, ‘Mamoru Hosoda Still Has Hope for the Future of the Internet’, Vulture, 14 January 2022, <https://www.vulture.com/2022/01/belle-director-mamoru-hosoda-interview.html>, accessed 24 January 2022. Work on this international production proceeded through the pandemic, often online. ‘We can use the internet, which is, of course, a big theme in Belle […] to actually help the production of the movie, itself,’ Hosoda marvels.[9]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in James Whitbrook, ‘Belle’s Mamoru Hosoda Tells Us Why He Keeps Making Stories for the Internet Age’, Gizmodo, 14 January 2022, <https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2022/01/belles-mamoru-hosoda-tells-us-why-he-keeps-making-stories-for-the-internet-age/>, accessed 24 February 2022. The potential of our increasingly digital world, both positive and negative, sits at the centre of Belle’s story; the director says that his intention was to offer his young viewers an exemplar of online hope. ‘If there was a much more globally adopted and fairer type of world that can exist digitally,’ Hosoda poses, ‘what would people do [with it]?’[10]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Eli Friedberg, ‘Mamoru Hosoda on Creating an Idealized Digital World in Belle’, The Film Stage, 12 January 2022, <https://thefilmstage.com/mamoru-hosoda-on-creating-an-idealized-digital-world-in-belle/>, accessed 24 February 2022.

Music makes the people come together

In Belle, U is a cramped, chaotic megalopolis ‘packed with these skyscraper-like structures’, where ‘it’s hard to tell where the horizon starts and where it ends’[11]Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. – this disorienting realm, Hosoda says, constructed to show ‘how much [the internet has] come to reflect the real world, including the bad’.[12]Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit. Cutting through the tumult and connecting the virtual world to the real one is music, which Hosoda sees as the one global artform: something easily accessible and universal.

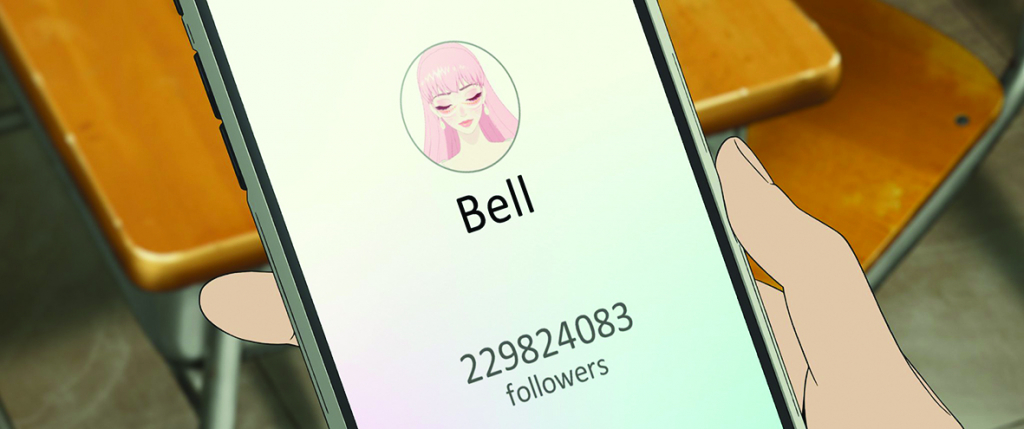

Music turns Belle into an online celebrity, but it’s also Suzu’s way of dealing with grief, finding healing and connecting with others: ‘I want to picture a world where a simple song can make the difference,’ she sings, in one of Belle’s grand musical numbers. ‘We didn’t want to tell the classic story of a girl from the suburban countryside who rises to pop stardom,’ Hosoda says, ‘but more a story about a soul that was somehow suppressed seeking freedom and attaining that strength through this journey.’[13]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Egan, op. cit.

Her path first crosses with Dragon’s during a Belle concert staged in a ‘spherical stadium’ within U, a giant panopticon that resembles the interior of a death star; the potency of her music is conveyed through animated electrical waves, spirals, helices and stars. In a case of reality catching up with Hosoda’s forward-looking story, the global pandemic found live performances, having been prohibited in real-world spaces, migrating online. This was mostly through direct-to-camera performances, but more futurist minds staged gigs in virtual realms like Minecraft,[14]See, for example, Cat Zhang, ‘How the Hell Do You Throw a Music Festival in Minecraft?’, Pitchfork, 1 May 2020, <https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/how-the-hell-do-you-throw-a-music-festival-in-minecraft/>, accessed 24 February 2022. suggesting a new avenue for live music.

Avatars, anonymity and identity

In Beauty and the Beast, the protagonist’s beau is a handsome prince cursed to live as a hideous beast. Hosoda draws not just from the Disney film that influenced him, but also from a long history of folk stories ‘in which characters are transformed into animals to express the great sadness of humanity’.[15]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Tarik Khaldi, ‘Belle: Interview with Mamoru Hosoda’, Festival de Cannes website, updated 16 July 2021, <https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/74-editions/retrospective/2021/actualites/articles/belle-linterview-de-mamoru-hosoda-1>, accessed 24 February 2022. What was once the province of fairytale has turned commonplace online, where people transform into avatars. ‘We […] have the version of ourselves that exists in reality and another projection that exists in the internet,’ Hosoda says.[16]Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. Through U’s fanciful ‘body sharing’ technology, avatars aren’t consciously constructed by their users, but instead scraped from their biometric data – thus seen as being true reflections of their personalities, perhaps even truer than how they appear in meatspace. Belle’s beauty is a projection of Suzu’s hidden inner light and musical gifts; Dragon’s beastliness is the monstrous embodiment of his real-world suffering.

Within the world of U, the ultimate punishment is to be ‘unveiled’ – having your offline identity revealed online. ‘It seems like the worst thing for young people on social media is to be found out,’ Hosoda explains. ‘They enjoy the freedom of being anonymous and are scared of people finding out who they are.’[17]Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit.

Wielding the threat of unveiling are the Justices, an embodiment of the internet’s morality police, rendered as gung-ho superheroes (with the added satirical wrinkle that their policing is an exercise in corporate sponcon). Their leader, Justin (Toshiyuki Morikawa) – whom Hosoda describes as ‘a very American character’[18]ibid. – sees himself as the ultimate arbiter of justice, personifying the ugliness of moral certitude, superiority and power. ‘Because there are no police on the internet, some people believe themselves to be cops,’ Hosoda explains. ‘One of the interesting things about the internet is that everyone believes they’re right. There’s no room for self-doubt. Maybe that’s not the internet but just humanity, and the internet is revealing it and blowing it up bigger.’[19]ibid.

The perils and potential of the internet

Belle explores human behaviour through the prism of the internet, which can amplify people’s best and worst behaviours. Hosoda first explored online possibilities over two decades ago in the anime series Digimon: Digital Monsters, which depicts the internet as a wide-open space filled with potential. U’s darker, more tumultuous landscape reflects the contemporary internet, whose deleterious effects on human society – from weaponised disinformation and derailing of democratic processes[20]See Zack Beauchamp, ‘Social Media Is Rotting Democracy from Within’, Vox, 22 January 2019, <https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/1/22/18177076/social-media-facebook-far-right-authoritarian-populism>, accessed 24 February 2022. to increased alienation and mental health problems[21]See Alice G Walton, ‘New Studies Show Just How Bad Social Media Is for Mental Heath’, Forbes, 16 November 2018, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/alicegwalton/2018/11/16/new-research-shows-just-how-bad-social-media-can-be-for-mental-health/?sh=65a1fa377af4>, accessed 24 February 2022. – sit at the centre of modern life. ‘We’ve carried a lot of our issues into the internet space,’ Hosoda laments. ‘The toxicity, a lot of negativity.’[22]Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit.

Belle depicts that most familiar of negative net experiences: the endless barrage of criticisms and outrage. For Suzu, online judgement and hostility is entwined with her formative trauma: online news reports about her mother’s death come replete with comment-section moralisers criticising her heroic deed (‘She practically committed suicide’; ‘She died for some stranger’s kid and abandoned her own’; ‘She shouldn’t have tried to be a hero’).

When Suzu performs for the first time as Belle, we hear an array of negative comments (‘Shut up!’; ‘Stop showing off’; ‘Look at those freckles’), and as her fame increases, the chorus of critiques grows louder, amplified to a din by the internet’s echo-chamber effect – the ‘pile-on’ of negative comments represented as a literal pile-on. But Hosoda makes sure to show that this isn’t a strictly digital phenomenon, with Suzu also overhearing girls gossiping about her at school, judgemental and jealous of her long-time friendship with high school heart-throb Shinobu (Ryō Narita).

Through U’s fanciful ‘body sharing’ technology, avatars aren’t consciously constructed by their users, but instead scraped from their biometric data – thus seen as being true reflections of their personalities.

Belle isn’t out to make a simple critique of the internet. The film also shows that it can be a place of self-discovery, with great potential for positivity. ‘Oftentimes, the internet is depicted as this dystopian space that strips us of our humanity,’ Hosoda says. ‘I want to show the internet as not a place to be attacked but a place to discover yourself and find hope.’[23]Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit.

Using the virtual for real-world good

When Hosoda first explored the early internet, he ‘was fascinated by this idea that […] these big events or phenomena that occur [online] can in some way, shape, or form affect our reality’.[24]Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. Having previously explored this idea in Summer Wars, he dives deeper into it with Belle. The film raises numerous real-world issues, from the oppression of high school social strata to isolation, bullying and domestic violence, and how combating them takes the work of a community. The internet is a place where communities can blossom, but the promises of online ‘connection’ have, sadly, been used by tech giants as cover to drag us into an age of surveillance capitalism;[25]See John Naughton, ‘“The Goal Is to Automate Us”: Welcome to the Age of Surveillance Capitalism’, The Guardian, 20 January 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jan/20/shoshana-zuboff-age-of-surveillance-capitalism-google-facebook>, accessed 24 February 2022. and internet stan armies and morality mobs by this point seem like they’re causing far more harm than good.[26]See Rebecca Jennings, ‘Stop Canceling Normal People Who Go Viral’, Vox, updated 21 January 2022, <https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22716772/west-elm-caleb-couch-guy-tiktok-cancel>, accessed 24 February 2022.

But Hosoda, who makes films both about and for young people – ‘My movies are aimed at people who are going to be living in the next generation’[27]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Vijn, op. cit. – makes sure that Belle, for all its critiques of the internet, offers its audiences the potential for hope and change. ‘Younger generations have to live with the internet,’ he says. ‘They have to really look at how they are going to interact with [it], how they will take advantage of it […] They have to look at it from more of a positive perspective.’[28]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Rich Juzwiak, ‘Belle Presents an Eye-popping Vision of the Internet’s Potential for Beauty’, Jezebel, 14 January 2022, <https://jezebel.com/belle-presents-an-eye-popping-vision-of-the-internets-p-1848353315>, accessed 24 February 2022.

Seen through that lens, the marketing copy of U, which initially seems like tech satire, plays as genuinely sincere. Suzu is initially seduced by its corporate pitch – ‘You can’t start over in reality, but you can start over in U’ – and ultimately lives out its most ambitious promise to users, which echoes the grand hopes Hosoda has imbued Belle with: ‘You can live as another you. You can start a new life. You can change the world.’

Endnotes

| 1 | Internet shorthand for ‘in real life’. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Ard Vijn, ‘Belle Interview: Director Hosoda Mamoru Provides Hope for the Future’, ScreenAnarchy, 12 January 2022, <https://screenanarchy.com/2022/01/belle-interview-director-hosoda-mamoru-provides-hope.html>, accessed 23 February 2022. |

| 3 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Nobuhiro Hosoki, ‘An Exclusive Interview with Director Mamoru Hosoda on Belle’, CinemaDailyUS, 17 January 2022, <https://cinemadailyus.com/interviews/an-exclusive-interview-with-director-mamoru-hosoda-on-belle/>, accessed 23 February 2022. |

| 4 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Andrew Webster, ‘Belle Director Mamoru Hosoda on Creating a Metaverse Fairy Tale’, The Verge, 11 January 2022, <https://www.theverge.com/22866629/belle-mamoru-hosoda-director-interview>, accessed 23 February 2022. |

| 5 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Gregory Ellwood, ‘Mamoru Hosoda on Creating a Virtual Beauty and the Beast for Belle [Interview]’, The Playlist, 17 January 2022, <https://theplaylist.net/mamoru-hosoda-belle-interview-20220117/>, accessed 23 February 2022. |

| 6 | Toussaint Egan, ‘Belle Is the Virtual World Anime that Mamoru Hosoda Always Wanted to Make’, Polygon, 12 January 2022, <https://www.polygon.com/22870380/belle-mamoru-hosoda-interview>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 7 | ibid. |

| 8 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Rafael Motamayor, ‘Mamoru Hosoda Still Has Hope for the Future of the Internet’, Vulture, 14 January 2022, <https://www.vulture.com/2022/01/belle-director-mamoru-hosoda-interview.html>, accessed 24 January 2022. |

| 9 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in James Whitbrook, ‘Belle’s Mamoru Hosoda Tells Us Why He Keeps Making Stories for the Internet Age’, Gizmodo, 14 January 2022, <https://www.gizmodo.com.au/2022/01/belles-mamoru-hosoda-tells-us-why-he-keeps-making-stories-for-the-internet-age/>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 10 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Eli Friedberg, ‘Mamoru Hosoda on Creating an Idealized Digital World in Belle’, The Film Stage, 12 January 2022, <https://thefilmstage.com/mamoru-hosoda-on-creating-an-idealized-digital-world-in-belle/>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 11 | Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. |

| 12 | Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit. |

| 13 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Egan, op. cit. |

| 14 | See, for example, Cat Zhang, ‘How the Hell Do You Throw a Music Festival in Minecraft?’, Pitchfork, 1 May 2020, <https://pitchfork.com/thepitch/how-the-hell-do-you-throw-a-music-festival-in-minecraft/>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 15 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Tarik Khaldi, ‘Belle: Interview with Mamoru Hosoda’, Festival de Cannes website, updated 16 July 2021, <https://www.festival-cannes.com/en/74-editions/retrospective/2021/actualites/articles/belle-linterview-de-mamoru-hosoda-1>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 16 | Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. |

| 17 | Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit. |

| 18 | ibid. |

| 19 | ibid. |

| 20 | See Zack Beauchamp, ‘Social Media Is Rotting Democracy from Within’, Vox, 22 January 2019, <https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2019/1/22/18177076/social-media-facebook-far-right-authoritarian-populism>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 21 | See Alice G Walton, ‘New Studies Show Just How Bad Social Media Is for Mental Heath’, Forbes, 16 November 2018, <https://www.forbes.com/sites/alicegwalton/2018/11/16/new-research-shows-just-how-bad-social-media-can-be-for-mental-health/?sh=65a1fa377af4>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 22 | Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. |

| 23 | Hosoda, quoted in Motamayor, op. cit. |

| 24 | Hosoda, quoted in Webster, op. cit. |

| 25 | See John Naughton, ‘“The Goal Is to Automate Us”: Welcome to the Age of Surveillance Capitalism’, The Guardian, 20 January 2019, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/jan/20/shoshana-zuboff-age-of-surveillance-capitalism-google-facebook>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 26 | See Rebecca Jennings, ‘Stop Canceling Normal People Who Go Viral’, Vox, updated 21 January 2022, <https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22716772/west-elm-caleb-couch-guy-tiktok-cancel>, accessed 24 February 2022. |

| 27 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Vijn, op. cit. |

| 28 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Rich Juzwiak, ‘Belle Presents an Eye-popping Vision of the Internet’s Potential for Beauty’, Jezebel, 14 January 2022, <https://jezebel.com/belle-presents-an-eye-popping-vision-of-the-internets-p-1848353315>, accessed 24 February 2022. |