The Matrix (Lana & Lilly Wachowski, 1999) remains a rare 1990s blockbuster to have aged well. In an era of franchise films and intimidating special-effects budgets, the spark of originality that ignited the cyberpunk classic has endured where its contemporaries have largely slid into obscurity. The Matrix – filmed largely in Sydney – is well crafted, distinctive and engaging throughout, filled with compelling ideas and exciting action. Though its sequels aren’t quite of the same pedigree, it’s been durable enough to warrant a continuation, still filming at the time of writing.[1]See Justin Kroll, ‘Matrix 4 Officially a Go with Keanu Reeves, Carrie-Anne Moss and Lana Wachowski (EXCLUSIVE)’, Variety, 20 August 2019, <https://variety.com/2019/film/news/matrix-4-keanu-reeves-carrie-anne-moss-lana-wachowski-1203307955/>, accessed 30 October 2020.

The film’s also jam-packed with intriguing scientific ideas, falling neatly in the middle ground between ‘hard’ science fiction – a subgenre driven by near-academic obsession with scientific accuracy – and the more accessible end of the genre. Sure, the Wachowskis’ screenplay dabbles in ideas about how neural pathways and computers could program human memory … but, in practice, that means that Keanu Reeves now knows kung-fu.

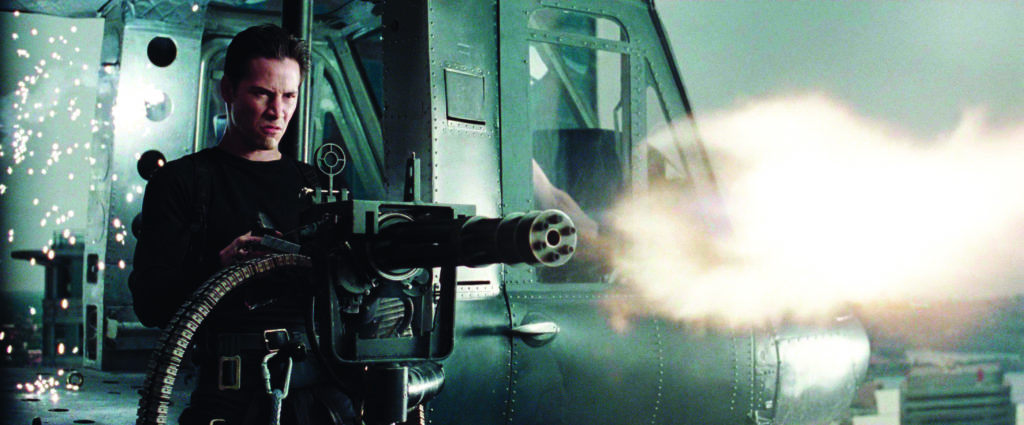

With all that scientific goodness in its marrow and lowbrow thrills on the surface, The Matrix can be leveraged as a compelling hook for a secondary Science lesson. I don’t know that I’d recommend screening the entirety of the film in the classroom, mind you. Its duration exceeds two hours, cutting into necessary curriculum time. Furthermore, some of its scenes of gun violence seem a little more fraught in a post-Columbine world; as much as I found the lobby shootout exciting as a teenager, I don’t know that I’d feel comfortable screening it for a class of secondary students nowadays.

Brains in vats, malicious demons and simulations

I spent a semester at university studying a course titled ‘Philosophy of Film and Television’. Given I was completing a Mathematics degree, it was undeniably a bludge class, but it proved illuminating nonetheless. One of the films covered was, naturally, The Matrix – used as an introduction to the work of one René Descartes.

A seventeenth-century philosopher, mathematician and scientist, Descartes famously pondered our very reality. Asking how our minds could distinguish between the existence of an external world and a simulation thereof – say, one concocted by a malicious demon – he resolved that our external world did truly exist with the iconic conclusion: ‘I think, therefore I am.’[2]Originally written in French as ‘je pense, donc je suis’ in Descartes’ essay ‘Discourse on the Method’, published in 1637. Also commonly seen in Latin as ‘cogito, ergo sum’. But if we’re getting into historical philosophy with secondary students, best we stick to English! See René Descartes, ‘Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Seeking for Truth in the Sciences’, in The Philosophical Works of Descartes: Volume I, trans. Elizabeth S Haldane & GRT Ross, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1911, p. 101. Essentially, Descartes’ argument was that if our existence was artificial, then we would be conditioned not to doubt it – in questioning our reality, we confirm its existence. (And yes, I’m simplifying things somewhat here.)

As a foundational tenet of philosophy, Descartes’ thought experiment has endured and evolved. Modern philosopher Gilbert Harman reimagined this line of thinking for an age of computers: what if we were simply a brain in a vat, sent electronic stimuli to simulate our perceived reality? With the demon subtracted from the equation, is our ability to doubt our existence still sufficient evidence of said existence?[3]See Lance P Hickey, ‘The Brain in a Vat Argument’, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, <https://iep.utm.edu/brainvat/>, accessed 30 October 2020.

At this point, you might be scratching your head – either over the richness of such ideas or with puzzlement as to what on earth this discussion of philosophy has to do with a Cinema Science column. I’ve got two answers for that. The first is that Descartes’ contributions go beyond his famous quotation. You might have heard of the Cartesian plane – those x and y axes so frequently found in high school Mathematics and beyond – that takes its name from René himself. Oftentimes, introducing the Cartesian plane to junior secondary students, I’ve discussed Descartes’ other famous contributions. I find that this serves as a point of interest, but also as a reinforcement of the core of mathematics and science: to ask big questions and find tools with which to answer them. Like the archetypal cinematic hero and his nemesis, philosophy and mathematics aren’t so different after all.

When you start to question the very nature of the universe – from atoms to quarks through general relativity and quantum mechanics – the potential answers start edging up alongside philosophy.

At the upper ends of the secondary school spectrum, though, these questions pivot nicely into the senior Physics classroom. Granted, Descartes’ malicious demon is more aligned with questions of metaphysics, but at higher levels the distinctions between metaphysics and traditional physics are more blurred than you might expect. When you start to question the very nature of the universe – from atoms to quarks through general relativity and quantum mechanics – the potential answers start edging up alongside philosophy.

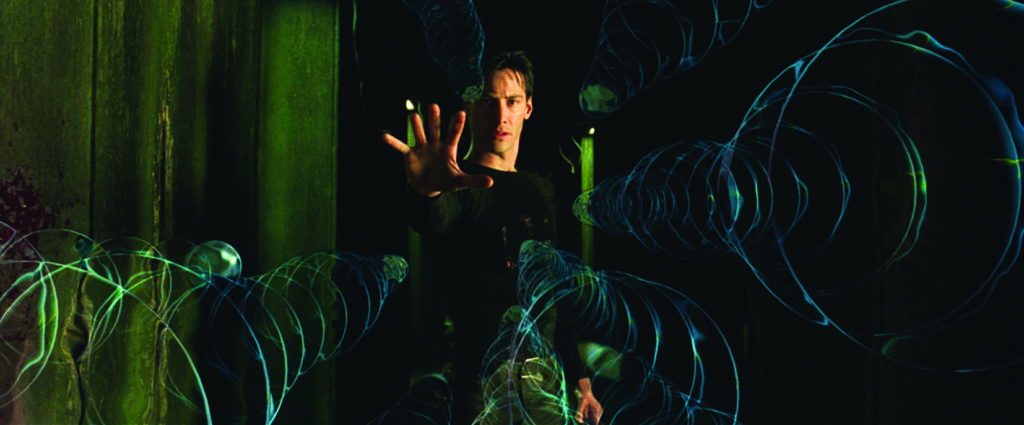

To wit: simulation theory. This is the perfectly plausible – currently neither proven nor disproven – hypothesis that our world is pretty much The Matrix:a sprawling computer simulation developed by an intelligence infinitely more sophisticated than our own (you might have heard Elon Musk talk about the subject[4]See Olivia Solon, ‘Is Our World a Simulation? Why Some Scientists Say It’s More Likely than Not’, The Guardian, 11 October 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/oct/11/simulated-world-elon-musk-the-matrix>, accessed 30 October 2020.). This is more than idle physicist daydreaming, too; many prominent scientists support the hypothesis. It does a bit to explain the weirdness of quantum mechanics (maybe the simulation processors are just breaking down!), while also extrapolating our own development trends in fields like virtual reality and artificial intelligence (AI). If you’re looking to really stretch the upper limits of your students’ understanding of physics, The Matrix presents a convenient opportunity to introduce such ideas.

Rise of the machines

On the subject of artificial intelligence, The Matrix is one of a long string of sci-fi narratives in which we are hoisted by our own robotic petard. The antagonists of The Matrix are machines created by humans centuries prior that eventually rose up against and enslaved their makers. While this isn’t the film’s most original idea – The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) is perhaps the best-known iteration of this plotline, though there are countless other examples – its scientific resonance is amplified by the screenplay’s preoccupation with intelligence in general.

What I mean is that the premise of the film digs into how we think in a way that a simpler execution could have elided entirely. There’s the revelation from Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving), an avatar of the machines, that their first attempt to simulate our reality was a utopian paradise rejected by the first wave of imprisoned humans – implying that our neurological architecture is, at the very least, a tad more complicated than stimulus response. Tank (Marcus Chong) programming Neo (Keanu Reeves) with a suite of martial-arts techniques and the ability to fly a helicopter is a neat plot device, granted, but it also opens up questions about learning. Would it be possible for us to master such complex skills through programming rather than training?

In the context of a discussion around contemporary artificial-intelligence research, there’s a bit to unpack here. The Matrix isn’t especially interested in how these nefarious machines became so intelligent as to overthrow humanity.[5]Though the animated spin-off anthology of short films, The Animatrix (various directors, 2003), occasionally touches on such ideas. But questions about how learning works, how artificial intelligence operates and what consciousness even is flow neatly from a familiarity with the film.

Though a compelling hook for a lesson, the potential problem of evil AI isn’t a particularly pertinent one. ‘The risk doesn’t come from machines suddenly developing spontaneous malevolent consciousness,’ explained artificial-intelligence researcher Stuart Russell in an interview with The Guardian.[6]Stuart Russell, quoted in Olivia Solon, ‘The Rise of Robots: Forget Evil AI – the Real Risk Is Far More Insidious’, The Guardian, 30 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/aug/30/rise-of-robots-evil-artificial-intelligence-uc-berkeley>, accessed 30 October 2020. ‘It’s important that we’re not trying to prevent that from happening because there’s absolutely no understanding of consciousness whatsoever.’ You might, however, have an interesting conversation about what consciousness actually is. The concept is nebulous, yet it presents significant ethical ramifications in the AI sphere.

I mentioned learning before, and this is where I’d focus my Matrix-inspired conversation on artificial intelligence. It sure feels like we’re in ‘the future’ now. Granted, we don’t have Jetsons-esque robots doing our housework for us (though maybe I need to rethink that assertion given the existence of Roombas); yet artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly ubiquitous, even if we’re not always aware of it. Every time you use a half-decent search engine, your results come from machine-learning algorithms. Apps like Instagram use filters to make us look nicer – or like an animal, whatever – developed from similar principles.

A discussion of machine learning – what it looks like, how it’s developed and the increasing role it’s going to play in developing technology – pivots nicely from a viewing of The Matrix or sections thereof. One handy side effect of such an exploration, whether in the Science or Technology classroom, is an opportunity for students to reflect upon their own learning and, in the process, perhaps develop their own techniques using some of the underlying principles of neurology and modern machine learning.

Batteries and biology

There’s a decided disinterest in the underpinning mechanics of the matrix in The Matrix. I’m referring specifically to the conceit that humans’ enslavement is required by the machines for a power source, which provides necessary foundation for the film’s premise but doesn’t hold up to logistical – nor scientific – scrutiny.

Still, it’s interesting to examine why a system of humans hooked up to an elaborate virtual-reality system might not be the best way to generate power. You don’t need a scientific background to see it doesn’t hold much water – why not use a less sophisticated animal species that doesn’t require such convoluted mental stimulation? – but a scientific exploration of how batteries and biological energy function would help to clarify why the screenplay might gloss over this piece of the jigsaw puzzle.

Organic batteries exist, of course, depending on how you look at it. Our bodies process our food into chemical energy; a cyclist powering their headlamp with every pump of their legs might qualify, too. Then there’s the classic science experiment of the ‘lemon battery’,[7]See, for example, ‘Generate Electricity with a Lemon Battery’, Scientific American, 23 July 2015, <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/generate-electricity-with-a-lemon-battery/>, accessed 30 October 2020. which you can pivot to neatly from The Matrix – and then unpack why we don’t tend to actually power our laptops and smartphones with the fruit scattered around our house. Energy in a contemporary context is about efficiency, and there’s a Science report waiting to be written about why humans aren’t as efficient as alternative sources, even if the machines in question are in a future that lacks materials like fossil fuels.

The film’s deft elision of the particulars of its premise isn’t necessarily because of any scientific implausibility, mind you. The Matrix isn’t the kind of science fiction that dwells upon the science in its fiction; rather, the Wachowskis’ focus is conjuring an atmosphere of alienation and disconnection from reality. Beyond its special effects and martial-arts showdowns, this is a film invested in exploring the sensation of feeling unwelcome in one’s own world.

Specifically, The Matrix is broadly read as an allegory for the trans experience. This interpretation of the film has increased in popularity over the years, reinforced by its directors each coming out as transgender – and, more recently, by a viral Twitter thread from an official Netflix account.[8]Netflix Film, Twitter thread dated 7 August 2020, <https://twitter.com/netflixfilm/status/1291439319245234177>, accessed 30 October 2020. Though this analysis of the film is better suited to an English or Media Arts classroom, I think a Science teacher using the film as a platform in a biological context would be doing their students a disservice not to touch upon the science associated with trans issues.

Too often, transphobes – prominently represented nowadays by trans-exclusionary radical feminists[9]See Katelyn Burns, ‘The Rise of Anti-trans “Radical” Feminists, Explained’, Vox, updated 5 September 2019, <https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/9/5/20840101/terfs-radical-feminists-gender-critical>, accessed 30 October 2020. – point to gender fluidity and associated concepts as unscientific. This stems from an oversimplified understanding of biological sex, limited to chromosomes and disregarding the existence of intersex individuals or the distinction between sex and gender.[10]See Simón(e) D Sun, ‘Stop Using Phony Science to Justify Transphobia’, Scientific American, 13 June 2019, <https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/stop-using-phony-science-to-justify-transphobia/>, accessed 30 October 2020. Examining all this through the lens of The Matrix – and its accessible, if somewhat opaque, trans themes – helps equip students to engage with these topics with a more informed worldview.

Endnotes

| 1 | See Justin Kroll, ‘Matrix 4 Officially a Go with Keanu Reeves, Carrie-Anne Moss and Lana Wachowski (EXCLUSIVE)’, Variety, 20 August 2019, <https://variety.com/2019/film/news/matrix-4-keanu-reeves-carrie-anne-moss-lana-wachowski-1203307955/>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Originally written in French as ‘je pense, donc je suis’ in Descartes’ essay ‘Discourse on the Method’, published in 1637. Also commonly seen in Latin as ‘cogito, ergo sum’. But if we’re getting into historical philosophy with secondary students, best we stick to English! See René Descartes, ‘Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Seeking for Truth in the Sciences’, in The Philosophical Works of Descartes: Volume I, trans. Elizabeth S Haldane & GRT Ross, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1911, p. 101. |

| 3 | See Lance P Hickey, ‘The Brain in a Vat Argument’, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, <https://iep.utm.edu/brainvat/>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 4 | See Olivia Solon, ‘Is Our World a Simulation? Why Some Scientists Say It’s More Likely than Not’, The Guardian, 11 October 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/oct/11/simulated-world-elon-musk-the-matrix>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 5 | Though the animated spin-off anthology of short films, The Animatrix (various directors, 2003), occasionally touches on such ideas. |

| 6 | Stuart Russell, quoted in Olivia Solon, ‘The Rise of Robots: Forget Evil AI – the Real Risk Is Far More Insidious’, The Guardian, 30 August 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/aug/30/rise-of-robots-evil-artificial-intelligence-uc-berkeley>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 7 | See, for example, ‘Generate Electricity with a Lemon Battery’, Scientific American, 23 July 2015, <https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/generate-electricity-with-a-lemon-battery/>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 8 | Netflix Film, Twitter thread dated 7 August 2020, <https://twitter.com/netflixfilm/status/1291439319245234177>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 9 | See Katelyn Burns, ‘The Rise of Anti-trans “Radical” Feminists, Explained’, Vox, updated 5 September 2019, <https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/9/5/20840101/terfs-radical-feminists-gender-critical>, accessed 30 October 2020. |

| 10 | See Simón(e) D Sun, ‘Stop Using Phony Science to Justify Transphobia’, Scientific American, 13 June 2019, <https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/stop-using-phony-science-to-justify-transphobia/>, accessed 30 October 2020. |