A quarter of a century later, it’s hard to overstate the impact of Babe (Chris Noonan, 1995). Sure, you can point to its box-office success or its seven Academy Award nominations – including for Best Picture! – but its reach was wider than the industry. ‘That’ll do, pig’ entered everyday parlance (for a while, at least), and the Warcraft franchise freely cribbed the film’s ‘password’ for laughs. The film even launched its own franchise – of sorts – with producer George Miller directing a divisive sequel, Babe: Pig in the City (1998).

The film holds up, too. Buoyed by an optimistic spirit shared with its titular piglet, Babe is a heartwarming family film with just enough teeth to engage all audiences. The fact that it’s largely culturally forgotten and that its running time is conveniently divided into chapters makes it a convenient inclusion into any classroom looking to fill time towards the end of a semester.

Ah, but Babe is more than a trifling distraction. In this edition of Cinema Science, we’ll consider the scientific and ethical questions prompted by the film, in a framework suited to upper primary or junior secondary classrooms. How do farms run? How do animals think? And just how does one actually herd a flock of stubborn sheep? Let’s find out …

‘The way things are’

For the majority of Babe, we see the operation of Hoggett Farm through the endearingly naive eyes of Babe (Christine Cavanaugh). The only pig on the farm, Babe receives a variety of perspectives on just how the farm operates. The sheep, led by Maa (Miriam Flynn), fear the ‘wolves’; while said wolves – sheepdogs Fly (Miriam Margolyes) and Rex (Hugo Weaving) – have a strict dogma that emphasises order and authority. Ferdinand (Danny Mann), a duck attempting to usurp the job of the farm’s rooster, is somewhat more sceptical of just how the hierarchy plays out for animals like himself and young Babe.

It isn’t until late in the film that Babe comes to understand his place in this system, laid out to him with malicious glee by the family house cat (Russi Taylor):

Well, the cow’s here to be milked. The dogs are here to help the boss’s husband with the sheep. And I’m here to be beautiful and affectionate to the boss. The fact is that pigs don’t have a purpose […]

So why do the bosses keep a pig? The fact is that animals that don’t seem to have a purpose really do have a purpose. The bosses have to eat.

There’s a conversation to be had in a Science classroom about the nature of animals and their purpose on a farm – and how this might differ from the interactions that occur within ecosystems in the wild.

Of course, this is a family film; Babe remains safely uneaten as the credits roll. This conversation is interesting, nonetheless, in the way it lays out a utilitarian view of farm life: every animal with a place and every animal in its place (shades of Orwell here!). There’s a conversation to be had in a Science classroom about the nature of animals and their purpose on a farm – and how this might differ from the interactions that occur within ecosystems in the wild. This brings us to an even more provocative question: could we define a modern-day farm as an ecosystem?

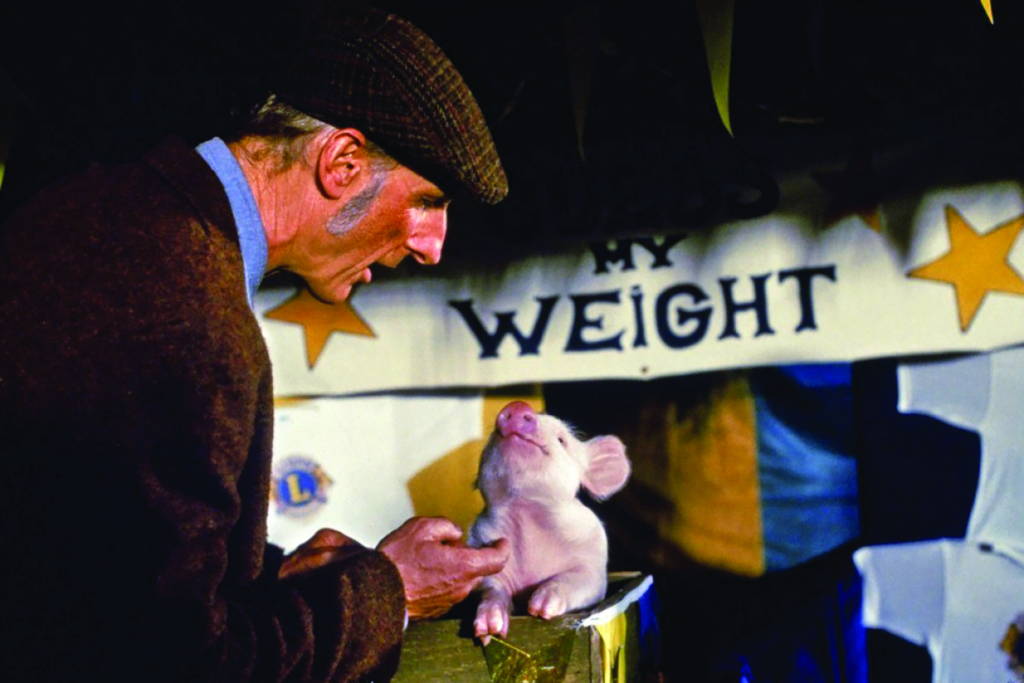

Let’s pause on ‘modern-day’ for a second. Even in 1995, it was clear that Arthur Hoggett (James Cromwell) wasn’t necessarily the most au fait with contemporary agricultural technology. He gets around on a horse and cart, and the notion of a fax machine – somewhat state-of-the-art at the time, if desperately archaic nowadays – is met with scepticism and a skerrick of fear. But for students raised in the city, Babe’s depiction of farming is probably closely aligned with their own understanding of what farms look like, give or take.

A discussion on this issue – with students sharing their own impressions of farms and farm life – could pivot into an exploration of advances in agricultural science. The Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture has produced a wonderful resource, ‘Engaging Students in STEM Using Agriculture’,[1]Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, ‘Engaging Students in STEM Using Agriculture’, 2018, available at <https://ezrwbvk28gx.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Engaging-Students-in-Stem-2020.pdf>, accessed 3 November 2021. that outlines innovations in seed germination, raising animals and testing soil, with a host of associated resources and activities. Students could engage in different sections of this individually, in small groups or as an entire class, subsequently researching what contemporary farms look like. If time permits, this could even call for an excursion!

‘Pigs are definitely stupid’

Babe is a wonderful film, but – if we’re being honest – it’s not the most original idea. Granted, a pig succeeding as a sheepdog has a spark of something, but the driving force behind the narrative is the same idea that’s powered hundreds of children’s stories: what if [ordinary thing] could talk? In this case, the ordinary things are farmhouse animals, who converse and engage with one another as though they were as smart as us.

While we’re quite confident that other animals aren’t as intelligent as humans – they haven’t gotten around to inventing Facebook, aeroplanes and late capitalism, after all – measuring the intelligence of other species is easier said than done. Are pigs really stupider than dogs? How can we compare mice to geese?

Behavioural tests are one way to do it. An article from The Atlantic identifies two tests used by researchers to ascertain animals’ intelligence: the ‘pointing test’ and the ‘mirror test’.[2]Philip Sopher, ‘What Animals Teach Us About Measuring Intelligence’, The Atlantic, 28 February 2015, <https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/02/what-animals-teach-us-about-measuring-intelligence/386330/>, accessed 3 November 2021. In the former, animals conditioned to expect to be fed in a certain location are redirected by pointing; if they understand and respond to this gesture, they’re given a tick for intelligence. The mirror test, meanwhile, measures if an animal is able to recognise itself in a mirror. As the article identifies, however, these experiments are hardly infallible:

The pointer and mirror tests might also be ecologically inconsistent. Irene Pepperberg, an animal psychologist at Harvard who works with parrots, explains, ‘Mirror tests check whether a subject has self–recognition, but the test can be tricky. We gave the mark–test to one of my parrots. He saw the mark in the mirror, scratched at it for a couple of seconds, the mark didn’t go away, and he walked off. Parrots get gunk on their faces all the time when they feed, so what did the bird’s actions mean? Ditto for the point test: If an animal doesn’t have arms, hands, and fingers, what would pointing really mean?’[3]ibid.

Challenges like this identify the difficulty of measuring intelligence. Primatologist Frans de Waal puts it well: ‘I do think that we need to judge animals on their own terms. “Is the octopus smarter than a rat or smarter than a monkey?” That’s not really a good question. The question is: “What does the octopus do in its life, what does it need to do and does it have the intelligence to do so?”’[4]Frans de Waal, quoted in Kathleen Calderwood, ‘Why We’ve Been Testing Animal Intelligence All Wrong’, Saturday Extra with Geraldine Doogue, Radio National, updated 16 June 2016 <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/saturdayextra/do-we-really-know-how-smart-animals-are/7500722>, accessed 3 November 2021.

There’s a deep vein to explore here for budding scientists: the challenges of understanding something that’s so difficult to measure, and the difficulty of even defining ‘intelligence’ in the first place. These findings can be extended into education, helping students to recognise that underperforming on a standardised test or similar isn’t necessarily a measure of their intelligence, since the notion is so nebulous in the first place.

There’s a deep vein to explore here for budding scientists: the challenges of understanding something that’s so difficult to measure, and the difficulty of even defining ‘intelligence’ in the first place.

This is also, I feel, an appropriate time to touch upon the ethics of eating meat. Babe will prompt many to reconsider their fondness for pork, ham and bacon. In fact, the film’s human star, Cromwell, converted to veganism after working on the film.[5]See Goran Blazeski, ‘James Cromwell, the Actor Who Played Farmer Hoggett in Babe, Became a Vegan and Outspoken Animal Advocate Because of the Movie’, The Vintage News, 9 February 2017, <https://www.thevintagenews.com/2017/02/09/james-cromwell-the-actor-who-played-farmer-hoggett-in-babe-became-a-vegan-and-outspoken-animal-advocate-because-of-the-movie/>, accessed 3 November 2021. This is obviously a provocative topic of conversation – and one that would need to be carefully managed in any given classroom – but there’s a lot to unpack regarding our willingness to eat animals once we reflect upon how little we know about their intelligence. In the Science classroom, specifically, there’s also a debate to be had about how to balance the benefits of research on animals with its obvious ethical problems, though this might be straying a little far from the film as stimulus.

‘A pig that thinks it’s a dog’

In Babe’s opening minutes, our hero is orphaned: Babe’s mother is sent to a ‘place so wonderful that no pig had ever thought to come back’. Fly becomes Babe’s adoptive mother of sorts, providing guidance and care to the young pig. So perhaps it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the film’s triumphant conclusion involves Babe emulating Fly’s sheepdog talents … with a twist.

This storyline – that of a pig thinking he’s a dog – plays into the ubiquitous, heartwarming tales of animals raised by another species who grow up to emulate their adoptive parents. These stories aren’t pure fiction. A recent article in The Conversation provides examples of cross-species adoptions and ponders how to reconcile this behaviour with ‘evolutionary selfishness’.[6]Isabelle Catherine Winder & Vivien Shaw, ‘Animal Adoptions Make No Evolutionary Sense, so Why Do They Happen?’, The Conversation, 29 April 2021, <https://theconversation.com/animal-adoptions-make-no-evolutionary-sense-so-why-do-they-happen-159722>, accessed 3 November 2021. Maternal behaviour is easily justified by evolutionary theory – animals are preconditioned to support the continuation of their genetic code – but harder to justify when the subject of their maternal care is unrelated, let alone another species altogether!

Such questions prompt a conversation about the intersection of evolution and behaviour by considering Babe specifically. Is it plausible for a pig to emulate a dog in this fashion? Really, the question being drilled down into here leads to the old chestnut of ‘nature vs nurture’: how much of our behaviour is ingrained our genes, and how much is learned through experience? This conversation goes beyond why this particular pig might imitate his canine peers and into a deeper exploration of our evolving understanding of animal behaviour (and evolution).[7]You could also explore the kind of mimicry found in the wild at this point, though I’ll concede that it’s a bit of a stretch to step from Babe herding sheep to the mimics found in the wild.

While on the subject of herding sheep, there’s quite a bit of science associated with just how sheepdogs are able to rustle up a bunch of bovines. Although Babe’s strategy of rattling off an arcane password is squarely in the realm of (agricultural) science fiction, scientists who study sheepdogs have identified ‘two very simple rules’ that govern their herding strategy.[8]See ‘Why Herding Sheep Is Dogs’ Work’, ABC Science, 27 August 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2014/08/27/4075526.htm>, accessed 3 November 2021.

These rules are relatively intuitive: the dogs first gather the sheep together by ‘weaving around side-to-side at their backs’.[9]ibid. Once the sheep are congregated tightly enough, they just ‘drive them forward’.[10]‘Sheepdogs Use Simple Rules to Herd Sheep’, ScienceDaily, 26 August 2014, <https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140826205519.htm>, accessed 3 November 2021. While this revelation is unlikely to blow any budding Science students’ minds, the ramifications go beyond the farmyard. As a report on the study in ScienceDaily explains, ‘The findings could lead to the development of robots that can gather and herd livestock, crowd control techniques, or new methods to clean up the environment.’[11]ibid.

Babe might not have the same scientific scope as a film featuring time-travelling superheroes[12]See Dave Crewe, ‘Cinema Science: Assembling the Operations of Avengers: Endgame’, Screen Education, no. 95, 2019, pp. 56–63. or set in a post-apocalyptic Australia[13]See Dave Crewe, ‘Cinema Science: Deconstructing the Machinery of the Mad Max Films’, Metro, no. 209, 2021, pp. 78–83. (though it does share Miller’s fingerprints with the latter). But this humble tale of a naive pig who thinks he’s a dog has plenty to offer curious Science students. That’ll do.

Endnotes

| 1 | Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, ‘Engaging Students in STEM Using Agriculture’, 2018, available at <https://ezrwbvk28gx.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Engaging-Students-in-Stem-2020.pdf>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Philip Sopher, ‘What Animals Teach Us About Measuring Intelligence’, The Atlantic, 28 February 2015, <https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/02/what-animals-teach-us-about-measuring-intelligence/386330/>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 3 | ibid. |

| 4 | Frans de Waal, quoted in Kathleen Calderwood, ‘Why We’ve Been Testing Animal Intelligence All Wrong’, Saturday Extra with Geraldine Doogue, Radio National, updated 16 June 2016 <https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/saturdayextra/do-we-really-know-how-smart-animals-are/7500722>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 5 | See Goran Blazeski, ‘James Cromwell, the Actor Who Played Farmer Hoggett in Babe, Became a Vegan and Outspoken Animal Advocate Because of the Movie’, The Vintage News, 9 February 2017, <https://www.thevintagenews.com/2017/02/09/james-cromwell-the-actor-who-played-farmer-hoggett-in-babe-became-a-vegan-and-outspoken-animal-advocate-because-of-the-movie/>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 6 | Isabelle Catherine Winder & Vivien Shaw, ‘Animal Adoptions Make No Evolutionary Sense, so Why Do They Happen?’, The Conversation, 29 April 2021, <https://theconversation.com/animal-adoptions-make-no-evolutionary-sense-so-why-do-they-happen-159722>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 7 | You could also explore the kind of mimicry found in the wild at this point, though I’ll concede that it’s a bit of a stretch to step from Babe herding sheep to the mimics found in the wild. |

| 8 | See ‘Why Herding Sheep Is Dogs’ Work’, ABC Science, 27 August 2014, <https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2014/08/27/4075526.htm>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 9 | ibid. |

| 10 | ‘Sheepdogs Use Simple Rules to Herd Sheep’, ScienceDaily, 26 August 2014, <https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140826205519.htm>, accessed 3 November 2021. |

| 11 | ibid. |

| 12 | See Dave Crewe, ‘Cinema Science: Assembling the Operations of Avengers: Endgame’, Screen Education, no. 95, 2019, pp. 56–63. |

| 13 | See Dave Crewe, ‘Cinema Science: Deconstructing the Machinery of the Mad Max Films’, Metro, no. 209, 2021, pp. 78–83. |