On 24 August 2010, Satashi Kon died. The illustrator, animator and film director had – unbeknown to the public – been diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer on 18 May and given only six months, at best, to live. The swiftness of his demise meant his death, at just forty-six, came as a shock. Kon had become one of Japan’s most well-regarded and cultishly beloved anime auteurs, for his four feature films – Perfect Blue (1997), Millennium Actress (2001), Tokyo Godfathers (2003), Paprika (2006) – and his 2004 TV series Paranoia Agent. In a long public message posted on his blog after his death, titled ‘Sayonara’,[1]Available in English translation at ‘Satoshi Kon’s Last Words’, Makiko Itoh author website, 26 August 2010, <https://www.makikoitoh.com/journal/satoshi-kons-last-words>, accessed 14 May 2020. Kon detailed his final days: how his last few months had been spent preserving both the legal status and legacy of his films, while also ‘wait[ing] for death’. He closed the long, personal message with a sanguine sense of acceptance: ‘With my heart full of gratitude for everything good in the world, I’ll put down my pen. Now excuse me, I have to go.’[2]Satoshi Kon, quoted in ibid.

At the time of his death, Kon was working on his fifth feature film, a road movie following a trio of robots journeying through a distant-future world no longer populated by humans. In his final message, the director talks of the producers at Madhouse animation studios, whom he was making the film with, pledging that the movie would be brought to screen. But after his death, that undertaking was abandoned, stalling due to the absence of the auteur who was its driving force – and, more sadly, a lack of funds.[3]Mikikazu Komatsu, ‘Madhouse Founder Explains the Reason for Production Halt of Satoshi Kon’s Dreaming Machine Film’, Crunchyroll, 23 October 2018,<https://www.crunchyroll.com/anime-news/2018/10/22/madhouse-founder-explains-the-reason-for-production-halt-of-satoshi-kons-dreaming-machine-film>, accessed 14 May 2020. All too symbolically, Kon’s final movie was to be called Dreaming Machine. This title essentially captures Kon’s conception of cinema, and of animation: the way it could echo dreams and the subconscious. ‘The interaction of reality and dreams is a motif I still have interest in, and I keep bringing it back into my work,’ Kon said.[4]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Andrez Bergen, ‘A Tribute to Satoshi Kon’, Madman Entertainment blog, 8 September 2010, <https://www.madman.com.au/news/a-tribute-to-satoshi-kon/>, accessed 14 May 2020. Save for Tokyo Godfathers, far and away his most ‘realist’ work, Kon’s animations were out to capture the slipperiness of our subjective experience – especially with regard to the modern, tech-saturated landscape – by forever situating his narratives on the blurred lines between nightmare and dissociation, dreams and delusions, fantasy and reality, memory and movies.

While he was a student of Japanese anime, Kon also cited the huge influence of futurist-paranoia author Philip K Dick, the screen adaptation of Kurt Vonnegut’s famously non-linear novel Slaughterhouse-Five (George Roy Hill, 1972)[5]Bill Aguiar, ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon’, TOKYOPOP website, 25 April 2007, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20070427155103/https://www.tokyopop.com/667.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. and the 1980s films of Terry Gilliam[6]Bergen, op. cit. on his aesthetic. ‘Movies that you can watch once and understand entirely – that is the type of movie that I don’t really like,’ the director remarked.[7]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Nelson Pressley, ‘Satoshi Kon, Anime’s Dream Weaver’, The Washington Post, 17 June 2007, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2007/06/15/AR2007061500492.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. Kon’s own influence, too, wasn’t just limited to the world of anime. In the year of his death, two big-budget Hollywood spectacles were released that were indebted to his work. Darren Aronofsky had originally wanted to remake Perfect Blue as a live-action movie before instead authoring his own riff on its psychologically warped ideas, Black Swan (2010);[8]‘Darren Aronofsky Wanted to Remake Perfect Blue’, Dazed, 31 October 2017, <https://www.dazeddigital.com/film-tv/article/37923/1/darren-aronofsky-wanted-to-remake-perfect-blue>, accessed 14 May 2020. and, though Christopher Nolan claims he thought of the premise for Inception (2010) long before seeing Paprika,[9]‘Exclusive: Short Interview with Christopher Nolan About Inception’, YouTube, 8 July 2010, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSrBBMiZJSQ>, accessed 14 May 2020. there are striking similarities between the two pictures in premise, plot and even individual shots. Kon used the elasticity and unreality of animation to interrogate our subjective experiences of reality, giving him far more in common, artistically, with visionary live-action auteurs than with family-friendly animators or cool-dude manga authors.

Kon, who was born in Sapporo in 1963, cut his teeth as a manga artist, studying graphic design at Musashino Art University, and publishing his first manga as a student. Working at Young Magazine, he met Katsuhiro Ōtomo, whose manga Akira – turned into an iconic anime in 1988 – was being serialised in the magazine,[10]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Justin Sevakis, ‘Interview: Satoshi Kon’, Anime News Network, 21 August 2008, <https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interview/2008-08-21/satoshi-kon>, accessed 14 May 2020. and who would eventually hire Kon as his assistant and serve as his mentor. Kon would go on to work on Ōtomo’s live-action movie World Apartment Horror (1991), as key animator on the Ōtomo-penned Roujin Z (Hiroyuki Kitakubo, 1991), and as a writer and art director on the anthology anime Memories (Ōtomo, Koji Morimoto & Tensai Okamura, 1995). Kon wrote the section ‘Magnetic Rose’, wherein, in 2092, a deep-space salvage crew – in classic Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) fashion – responds to an SOS from an abandoned space station. There, they discover a baroque fantasia: a grand mausoleum in which an opera singer lives on, in robot form, in a holographic shrine to her memories. Along with its homages to Madama Butterfly and 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968), the forty-minute tale introduces the director’s particular predilections and preoccupations: the blurring of memory, illusion, delusion; technology attempting to erase the lines between real and ‘fake’; and using visual language to deliberately disorient the audience, making the viewer’s confusion echo the protagonist’s. In depicting shapeshifting, unreliable dream worlds that convey the subjectivity of the human experience, Kon constantly used the one cinematic effect, the match cut, to create a sense of disorientation and fluidity. By mirroring the visual composition of previous images, he moves through different realms – reality, fantasy, delusion, dream, video, movie, the unexplained – seamlessly, with no lines drawn between them. In making Perfect Blue, Kon ‘thought that it would be interesting if the viewers did not immediately grasp they were watching a flashback or a dream’,[11]Satoshi Kon, quoted in ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon, Director of Perfect Blue’, Perfect Blue official website, 4 September 1998, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/19991128232143/www.perfectblue.com/interview.html>, accessed 2 June 2020. and he used that approach, again and again, with Millennium Actress, Paprika and Paranoia Agent. Each scene bleeds into the next, and familiar filmic tropes – like someone waking up, signifying the prior scene was a dream – are wholly subverted, to the point where the audience, like the protagonists, struggle to remember where they ‘are’. ‘Dream scenes have a pattern: when you get wavy lines on the screen, it means that you’re entering a dream sequence,’ Kon would say. ‘But that kind of editing is totally boring.’ The director further observed that ‘there are many more ways of introducing dreams and flashbacks’, that ‘even if the shot or the scene changes, they must be linked within the flow of the story’.[12]ibid.

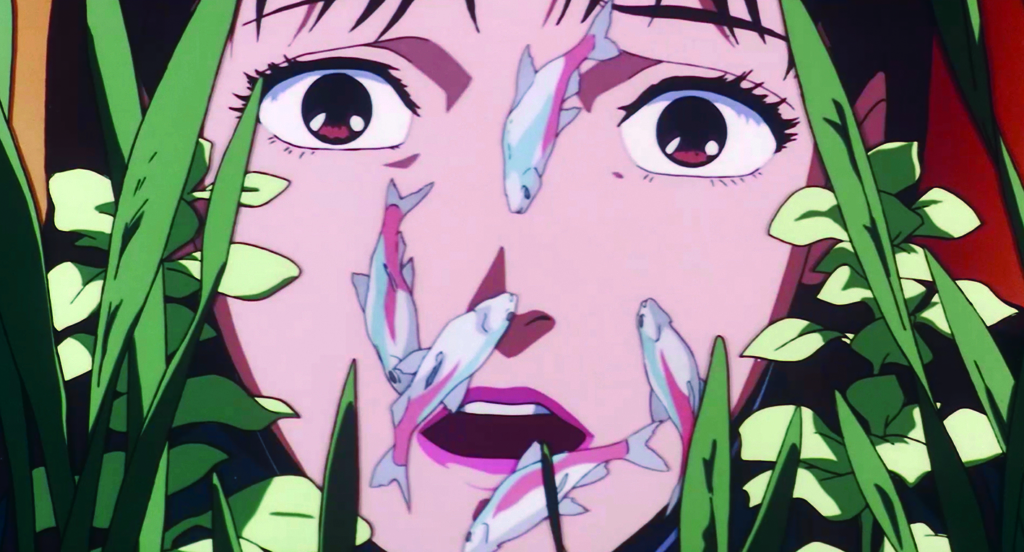

In Perfect Blue, the effect is out to convey the warped mind of its struggling protagonist, Mima (Junko Iwao). On opening, she quits her pop-idol girl group, CHAM!, to pursue being an actress. As she’s pressured into doing things for her career – acting in a rape scene, posing for a sexy photo shoot – her old fans turn on her; a mysterious third-party website seems to know the most intimate details of her life; and she’s soon haunted by an evil doppelganger, a cutesy past self that’s a sinister take on shōjo anime’s ‘magical girl’. Soon, Mima is struggling to tell the difference between her self and her shadow self, her life and her TV show, and finds herself pulled this way and that by managers, directors, other actors and, most of all, her fans. Though many elements of its story are comically dated – a menacing fax, browsing the ‘World Wide Web’ (‘that thing that’s been popular lately!’) via Netscape Navigator, her fan site’s URL evoking Angelfire – Perfect Blue perfectly presaged the digital era’s toxic, obsessive, possessive fandom. In particular, it draws from the Japanese world of pop idols, wherein middle-aged men bankroll the careers of teenage girls, often paying extra for ‘personal experiences’ (for more on this creepy subculture, see Kyoko Miyake’s 2017 documentary Tokyo Idols). Like so many contemporary fans, Mima’s followers feel a sense of ownership over her – this taken to an extreme by a character known only by his online handle, Me-Mania (Masaaki Ōkura), whose fandom is far more like stalking. In an early sequence, at Mima’s last ever show with CHAM!, we see Me-Mania in the crowd, and a point-of-view shot shows him lifting a hand up into frame, so that Mima appears to be dancing in his palm. Me-Mania is a nightmarish, horror-film-worthy antagonist, possibly the one killing people involved with Mima’s TV show; the character was inspired, in part, by Tsutomu Miyazaki, the ‘Otaku Murderer’, who abducted and killed four teenage girls from 1988 to 1989 (the crimes were blamed, by the moral panic–inducing media, on his obsessive consumption of manga).[13]See Jesse Hicks, ‘Otaku Anthropology: Exploring Japan’s Unique Subculture’, The Verge, 9 May 2012, <https://www.theverge.com/2012/5/9/3004622/otaku-spaces-patrick-galbraith-manga-anime-review>, accessed 14 May 2020. With his beast-like visage, Me-Mania is the notion of entitled fandom made manifest, and monstrous. But, like everything else in Perfect Blue, it’s possible he exists just in Mima’s mind.

Kon used the elasticity and unreality of animation to interrogate our subjective experiences of reality, giving him far more in common, artistically, with visionary live-action auteurs than with family-friendly animators.

Giving voice to these themes, characters say things like ‘We all create illusions within ourselves,’ and ‘It’s alright, there’s no way illusions can come to life,’ and ‘Are you sure you weren’t dreaming?’ – these lines repeated both in the show within the movie and in Mima’s ‘real’ life, whatever that might be. ‘Mima’s dramatic line, “Who are you?” is something we repeat several times, to give a special meaning to an ordinary question,’ Kon explained,[14]Kon, quoted in ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon, Director of Perfect Blue’, op. cit. this line spoken within the show, to other people, to her doppelganger and to herself. This disorientation is echoed by the way match cuts transform time and space into something forever fluid, with the loss of a sense of self reflected by mirrors and devices. The film is presented in 4:3 aspect ratio, that of pre-digital TV; Mima’s room features a TV, a computer monitor and a fish tank that all share the same 4:3 dimensions; and the production ‘shot Mima’s room as if it was being viewed on a TV screen […] to give a diluted sense of reality, as if all of the events were taking place within a TV’.[15]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Mary Beth McAndrews, ‘Satoshi Kon’s Otaku: The Dangers of Technological Fantasy’, The Artifice, 2 August 2014, <https://the-artifice.com/satoshi-kon-otaku-anime/>, accessed 14 May 2020. This disorientation and ‘the difficulty of figuring it out’, Kon says, is central to Perfect Blue. ‘So long as you accept that it’s meant to be inexplicable, that’s fine.’[16]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Andrew Osmond, ‘Animerica Interview: Satoshi Kon’, Animerica, vol. 7, no. 6, July 1999, p. 28, available at <https://www.animenostalgiabomb.com/satoshi-kon-interview-perfect-blue-animerica-june-1999/>, accessed 14 May 2020.

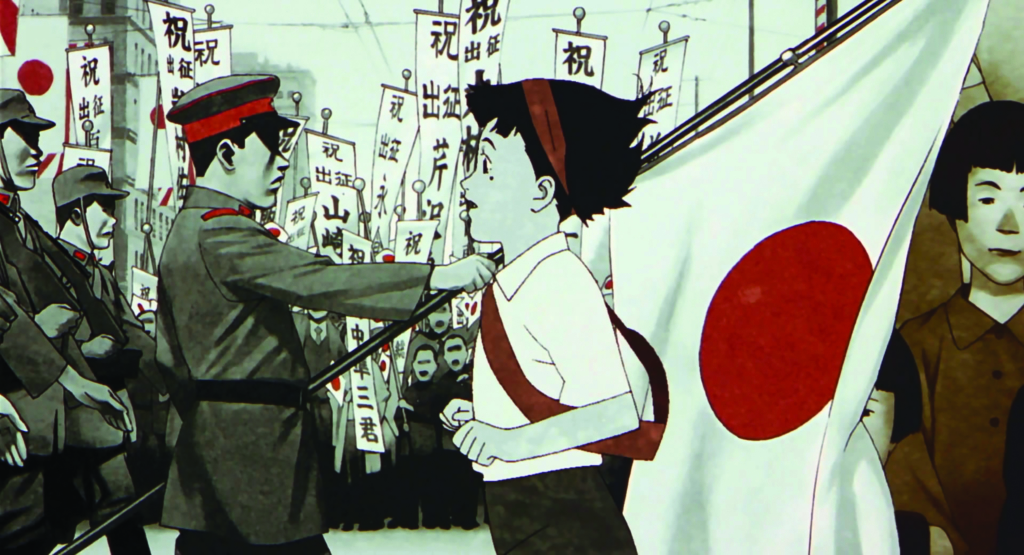

Upon the release of Millennium Actress, the follow-up to Perfect Blue, Kon described the two films as ‘two sides of the same coin’.[17]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Tom Mes, ‘Satoshi Kon’, Midnight Eye, 11 February 2002, <http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/satoshi-kon/>, accessed 14 May 2020. Each uses the same trompe-l’oeil visual effects, but his second feature employs them in sweeter ways – this a movie in which the blurring of the lines between cinema, memory and reality is beautiful, and the ardency of fandom is depicted as a kind of selfless, true love. ‘I had the intention of making the two films like sisters, through the depiction of the relationship between admirer and idol,’ Kon said. ‘They show the dark side and the light side of the same relationship.’[18]ibid. Again exploring the ‘uncertainty of memory and the mixture of reality and fiction’, Kon this time fashioned ‘sham bits and pieces [… to] tell one golden truth’.[19]Kon, quoted in Osmond, op. cit., p. 29. Here, a TV interviewer, Tachibana (Shōzō Īzuka), and his sidekick cameraman, Kyoji (Masaya Onosaka), track down an interview with reclusive Chiyoko (Miyoka Shōji), an ageing actress who disappeared from public life thirty years prior (this character is based on the reclusive film star Setsuko Hara, who permanently withdrew from public life upon the death of director Yasujirō Ozu[20]Simon Abrams, ‘Setsuko Hara: The Diva Who Left Japan Wanting a Lot More’, Politico, 1 April 2011, <https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2011/04/setsuko-hara-the-diva-who-left-japan-wanting-a-lot-more-067223>, accessed 14 May 2020.). Tachibana, it turns out, was once an underling at the Studio that Chiyoko was long ago contracted to act for, and has remained a devoted, ardent admirer over the decades. As the interview leads her into talking about her life and career, Millennium Actress deliberately blurs all manner of lines: the movies Chiyoko made and her memories becoming one and the same, with Tachibana and Kyoji, in a magical device, made active participants in this world, often physically tailing after her, camera in hand; the most meta-movie moments finding them filming the film crew filming her on set, making both memories and movies.

‘The human brain is mysterious. We can’t share the time axis in our memory with others,’ Kon observed;[21]Kon, quoted in Osmond, op. cit., p. 29. but, in this movie, it is shared. We move through different genres: samurai, kaiju, period piece, World War II, interstellar sci-fi. At one point, we enter into a landscape rendered as classic-Japanese-art tableau, in which all figures are revealed to be 2D (this is a device Kon reused in Paranoia Agent). As we dance between genres, Kon again employs smart match cuts, any door being opened sure to lead to a wholly different cinematic realm. Tachibana dubs this film-of-films-within-the-film that he’s making ‘The Seven Spectres: The Legend of Chiyoko Fujiwara’, and is revealed to be an active participant not merely in this retelling, but also in Chiyoko’s life – a kind of guardian angel, helping an old woman find closure through storytelling, through the catharsis of digging up the painful past. Here, movies are memories and magic; art is therapy, for those making and consuming it alike; and Kon even makes space for examining Japan’s difficult, imperial mid-twentieth-century years, with much of the movie’s history set against the Sino-Japanese war in Manchuria. The story is a tale of tragic love; Chiyoko – in her youth, her movies and her memories – is always pursuing an elusive, romanticised figure, a painter she met as a young girl. Through the process of being interviewed, she eventually admits she ‘was just chasing a shadow’ through much of her life. The closure – and finality – she finds comes with accepting the end of her own life, ready to chase after her (projected) love into the final frontier: space, in the cinematic imagery; but death, in her reality.

After Millennium Actress, Kon made his sole outlier film. While Tokyo Godfathers delivers plenty of inventive match cuts and smart methods of conveying visual information, not to mention cosmic coincidences and a dream sequence, it’s also a straight narrative that proceeds chronologically. And, for all its revealed secrets and plotted mysteries, it never leaves the viewer confused or disoriented; Kon confesses that he ‘intentionally made the story simple and focused on exposing the background of the characters’.[22]Pressley, op. cit. Riffing on the narrative of John Ford’s western 3 Godfathers (1948), Kon’s film finds three modern-day ‘outlaws’ – homeless people in snowy Tokyo – tasked with finding a home for an abandoned baby. Though there’s far too much action for it to be considered social realism, the film is definitely, defiantly full of figures (the homeless, runaways, transgender people, abused women, unwed mothers, immigrants) marginalised in Japanese society.

With his final feature, Paprika, Kon returned to his familiar working ways – albeit on a grander scale – fashioning a shapeshifting, mind-reeling narrative about technology that allows people (both protagonists and antagonists) to enter into the dreams of others. It was his riff on cyberterrorism, in terms of not just the stealing of data, but the rewiring of our brains by an endless stream of digital information and advertising.[23]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Edward Douglas, ‘Master “Anime-tor” Satoshi Kon’, ComingSoon.net, 22 May 2007,<https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/20417-excl-master-anime-tor-satoshi-kon>, accessed 14 May 2020. Here, the dream-invading technology falls into the archetypal ‘wrong hands’, which leads a grizzled detective and a team of scientists to pursue the villains through an ever-shifting array of dream worlds that soon begin to blur with reality. Kon wanted to make watching Paprika feel like both riding ‘an attraction in an amusement park’ and waking up from a ‘very odd, interesting or curious dream’.[24]Bergen, op. cit. It’s instantly disorienting: the cold open drops us into a circus-themed dream that turns into a menacing nightmare, before we follow our dream detective through a liquid landscape that changes genres, Kon riffing on classic movies – The Greatest Show on Earth (Cecil B DeMille, 1952), Tarzan the Ape Man (WS Van Dyke, 1932), Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953), Strangers on a Train (Alfred Hitchcock, 1951)[25]Bergen, op. cit. – as we rapidly shift, delirious, with scattershot dream logic. ‘If earlier [sleep] cycles are, say, artsy short films, then later cycles are like feature-length blockbuster movies,’ explains Dr Atsuko Chiba (Megumi Hayashibara), the researcher who’s been monitoring Detective Konakawa’s (Akio Ōtsuka) dreams, and who, we discover, travels through the dreamscape as the titular figure, equal parts guardian and avenging angel.

The definitive image of Paprika is a recurring absurdist parade in which frogs, cats, robots, costumed figures, schoolgirls and salarymen with flip-phone heads, polytheistic deities, shrines, statues, and anthropomorphised household appliances all march in increasingly delirious, demented fashion – this surrealist scene turning from the stuff of dreams to the stuff of nightmares, especially when they begin to march on the frontiers between the subconscious and the conscious. ‘Animation is supposed to be like a dream, pretty and nice,’ Kon observed. ‘When you see a Disney cartoon, you’re in a dream world of sweet animals and pretty flowers. The dream world in Paprika is quite the opposite – frightening and horrible.’[26]Satoshi Kon, quoted in Dave Kehr, ‘Anime Dreams, Transformed into Nightmares’, The New York Times, 20 May 2007, <https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/20/movies/20kehr.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. These dreams soon blur into one grand, terrifying ‘collective delusion’, a spoken notion that makes Paprika ripe for reading as parable. ‘On television and through the Internet people are being seduced by the sweetness of illusion and the sweetness of dreams,’ Kon would say, upon the picture’s release. ‘The amount of fantasy that people are being fed through the media has become disproportionate. I believe in a balance between real life and imagination. Anime should not be just another means of escape.’[27]ibid.

Kon wanted to make watching Paprika feel like both riding ‘an attraction in an amusement park’ and waking up from a ‘very odd, interesting or curious dream’.

At the end of Paprika, Detective Konakawa goes to the movies to see a (fictional) film called Dreaming Kids (perhaps this was supposed to represent Kon’s next, never-made movie, Dreaming Machine). As he walks to the box office, posters and marquees show the cinema is also screening Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress and Tokyo Godfathers. But those exploring Kon’s corpus shouldn’t forget about Paranoia Agent. The thirteen-episode series, of which Kon was creator and recurring director, finds Tokyo terrorised by a mysterious, bat-wielding assailant named Shonen Bat (Daisuke Sakaguchi) – or, in the American dub, Li’l Slugger – who’s maybe a boy on golden rollerblades, maybe a malevolent spirit, maybe just pure folklore. The series’ opening montage shows a host of people, all isolated, on their phones, many of them weaselling out of things – a societal turn away from collective good, towards individualism. ‘We must teach children the difference between the virtual world and the real world!’ barks a talking head on TV, before, of course, Kon sets about blurring lines between fantasy, reality and dreams. Each episode follows a different principal character, and many instalments are, artistically, discrete works unto themselves. The episode ‘A Man’s Path’ finds a cop often plunging into flights of line-drawn manga fantasy; ‘The Holy Warrior’ enters the delusional mind of a teenager who thinks he’s the hero of a medieval role-playing game; ‘Fear of a Direct Hit’ ricochets through time and memories, distorted by the perspective of an elderly interlocutor; ‘Radar Man’ blurs the lines between TV-show superheroism and Paranoia Agent’s own narrative; ‘ETC’ consists entirely of stories animating the gossip of small-minded neighbourhood biddies; and the very meta ‘Mellow Maromi’ goes into the production of an animated series within this animated series, at times plunging into its ultra-cartoonish world, but otherwise largely talking viewers through the technical logistics of television animation. That episode finds an office underling suffering paranoid hallucinations – which is, unsurprisingly, a device coursing through the show. The closing credits show its ensemble cast all asleep in the grass in a circle around a giant toy (Maromi, a super-kawaii cartoon dog that’s a recurring, totemic figure throughout the series), as if all participating in the one collective dream.

While Paranoia Agent’s first episode initially suggests the series could have a straight narrative – cops on the trail of a mystery assailant – it turns out to be one of Kon’s most convoluted stories: narrative realities forever collapsing in on themselves; no hard truths ever emerging; the inexplicable, as ever, proving ultimately triumphant. At the end of the series, in a post-credits scene following the final episode (titled, um, ‘The Final Episode’), a narrator, speaking over still images from the show’s many memorable moments, puts a bow on the series. His final words echo all that Kon prized, in both this series and his filmography:

The story that seems to have ended spins back to the place where it began. Following each stepping stone connecting the dots, you find the eternal castle of recurring dreams. No mystery remains unsolved forever. And no answer is without mystery. Well, then, we bid you farewell …

Endnotes

| 1 | Available in English translation at ‘Satoshi Kon’s Last Words’, Makiko Itoh author website, 26 August 2010, <https://www.makikoitoh.com/journal/satoshi-kons-last-words>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in ibid. |

| 3 | Mikikazu Komatsu, ‘Madhouse Founder Explains the Reason for Production Halt of Satoshi Kon’s Dreaming Machine Film’, Crunchyroll, 23 October 2018,<https://www.crunchyroll.com/anime-news/2018/10/22/madhouse-founder-explains-the-reason-for-production-halt-of-satoshi-kons-dreaming-machine-film>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 4 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Andrez Bergen, ‘A Tribute to Satoshi Kon’, Madman Entertainment blog, 8 September 2010, <https://www.madman.com.au/news/a-tribute-to-satoshi-kon/>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 5 | Bill Aguiar, ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon’, TOKYOPOP website, 25 April 2007, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/20070427155103/https://www.tokyopop.com/667.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 6 | Bergen, op. cit. |

| 7 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Nelson Pressley, ‘Satoshi Kon, Anime’s Dream Weaver’, The Washington Post, 17 June 2007, <https://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2007/06/15/AR2007061500492.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 8 | ‘Darren Aronofsky Wanted to Remake Perfect Blue’, Dazed, 31 October 2017, <https://www.dazeddigital.com/film-tv/article/37923/1/darren-aronofsky-wanted-to-remake-perfect-blue>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 9 | ‘Exclusive: Short Interview with Christopher Nolan About Inception’, YouTube, 8 July 2010, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSrBBMiZJSQ>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 10 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Justin Sevakis, ‘Interview: Satoshi Kon’, Anime News Network, 21 August 2008, <https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interview/2008-08-21/satoshi-kon>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 11 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon, Director of Perfect Blue’, Perfect Blue official website, 4 September 1998, archived at <https://web.archive.org/web/19991128232143/www.perfectblue.com/interview.html>, accessed 2 June 2020. |

| 12 | ibid. |

| 13 | See Jesse Hicks, ‘Otaku Anthropology: Exploring Japan’s Unique Subculture’, The Verge, 9 May 2012, <https://www.theverge.com/2012/5/9/3004622/otaku-spaces-patrick-galbraith-manga-anime-review>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 14 | Kon, quoted in ‘Interview with Satoshi Kon, Director of Perfect Blue’, op. cit. |

| 15 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Mary Beth McAndrews, ‘Satoshi Kon’s Otaku: The Dangers of Technological Fantasy’, The Artifice, 2 August 2014, <https://the-artifice.com/satoshi-kon-otaku-anime/>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 16 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Andrew Osmond, ‘Animerica Interview: Satoshi Kon’, Animerica, vol. 7, no. 6, July 1999, p. 28, available at <https://www.animenostalgiabomb.com/satoshi-kon-interview-perfect-blue-animerica-june-1999/>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 17 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Tom Mes, ‘Satoshi Kon’, Midnight Eye, 11 February 2002, <http://www.midnighteye.com/interviews/satoshi-kon/>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 18 | ibid. |

| 19 | Kon, quoted in Osmond, op. cit., p. 29. |

| 20 | Simon Abrams, ‘Setsuko Hara: The Diva Who Left Japan Wanting a Lot More’, Politico, 1 April 2011, <https://www.politico.com/states/new-york/albany/story/2011/04/setsuko-hara-the-diva-who-left-japan-wanting-a-lot-more-067223>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 21 | Kon, quoted in Osmond, op. cit., p. 29. |

| 22 | Pressley, op. cit. |

| 23 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Edward Douglas, ‘Master “Anime-tor” Satoshi Kon’, ComingSoon.net, 22 May 2007,<https://www.comingsoon.net/movies/features/20417-excl-master-anime-tor-satoshi-kon>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 24 | Bergen, op. cit. |

| 25 | Bergen, op. cit. |

| 26 | Satoshi Kon, quoted in Dave Kehr, ‘Anime Dreams, Transformed into Nightmares’, The New York Times, 20 May 2007, <https://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/20/movies/20kehr.html>, accessed 14 May 2020. |

| 27 | ibid. |