Shahrbanoo Sadat was born in Tehran in 1990, but she’s not Iranian. For the first eleven years of her life, she had no official national identity. The child of Afghan immigrants – who’d left Afghanistan after it was invaded by Soviet troops in 1979 – Sadat lived in a country that wouldn’t grant her a passport and never made her feel at home. After the American war on Afghanistan deposed the Taliban government in late 2001, there was suddenly a strong, concerted push to have Afghan expats ‘return home’. ‘The Iranian government produced an enormous propaganda campaign through the media,’ Sadat would recall years on. ‘[T]hey put on a lot of pressure. They kicked my father out from the factory that he was working in and [my] school denied to accept me’.[1]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Jeremy Elphick, ‘Wolf and Sheep – an Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat’, 4:3, 17 June 2017, <https://fourthreefilm.com/2017/06/wolf-and-sheep-an-interview-with-shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019. So Sadat’s father moved the family back to where he’d grown up: an isolated, impoverished rural village in central Afghanistan. With Sadat having spent her whole life living in urban Tehran, she didn’t speak a word of Hazaragi, the local language. ‘My father took me to a village with 10 houses and less than 100 people living in the middle of nowhere,’ Sadat recounts. ‘There was no electricity, no water, no signal for phones, no internet of course, nothing there at all […] Suddenly we had a flock of sheep, we had cows and chickens.’[2]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Tiana Malhotra, ‘Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat / Wolf and Sheep’, Film in Revolt, 19 June 2017, <http://www.filminrevolt.org/shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019.

This is not a familiar origin story for a filmmaker, especially after you learn that, when Sadat finally left the village to go to university in Kabul, it was to train in physics.[3]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Karin Schiefer, ‘Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Eurimages website, June 2019, p. 1, <https://rm.coe.int/interview-with-shahrbanoo-sadat/1680971c7f>, accessed 4 November 2019. But, in the Afghan capital, Sadat ended up signing on to study documentary filmmaking with Atelier Varan Kabul, a French-run workshop. At twenty, she both watched her first ever film in a cinema and made her first film, a short fiction work called Vice Versa One that cost her roughly US$100. Sadat later took part in the Cannes Cinéfondation residency, in 2010, as its youngest ever participant, and Vice Versa One premiered at the Cannes Film Festival itself the following year.[4]See Malhotra, op. cit.; and Taran N Khan, ‘“I Have a Dream and I Want to Fight for It So Hard”: Afghan Director Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Scroll.in, 6 July 2016, <https://scroll.in/reel/811179/i-have-a-dream-and-i-want-to-fight-for-it-so-hard-afghan-director-shahrbanoo-sadat>, accessed 4 November 2019.

It was in Kabul that Sadat met Anwar Hashimi, whom, despite being two decades her elder, she’s described as her best friend, and who’s served as her muse. The pair initially bonded over discovering they’d lived in the same remote village, though Hashimi had grown up there in the 1970s.[5]‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Raising Films, October 2016, <https://www.raisingfilms.com/interview-shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019. Hashimi would eventually share with Sadat his personal diary, an 800-page chronicle of his life. ‘He lived in central Afghanistan as a kid, was orphaned and ended up in a Russian orphanage in Kabul, went to Moscow then to Iran as a refugee [and] came back to Afghanistan,’ Sadat recounts.[6]Sadat, quoted in Schiefer, op. cit., p. 3. Inspired, she set out on an ambitious project: to make a ‘pentalogy’ – five films – inspired by Hashimi’s life, evoking different periods in Afghan history.

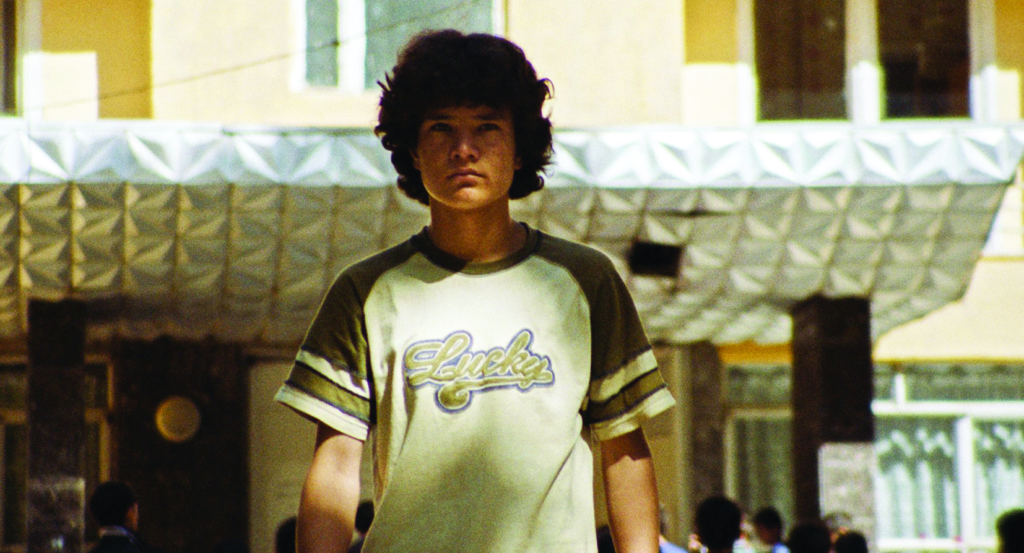

Its first entry, Wolf and Sheep (2016), captures the isolation and folklore of village living, drawing both from Hashimi’s experiences and Sadat’s own, evincing how traditional mountain societies seemingly didn’t change at all between the 1970s and the 2000s. ‘[I]t is kind of like my autobiographical life but also his,’ Sadat says;[7]Sadat, quoted in Malhotra, op. cit. the film’s two principal characters, Qodrat (Qodratollah Qadiri) and Sediqa (Sediqa Rasuli), are stand-ins for the writer and the director, and the scenario imagines life if they’d been childhood friends. Each character, and each actor, returns in The Orphanage (2019), in which Qodrat ends up in a state-run orphanage in Kabul in 1989, during the final days of a pro-Soviet government. It was, of course, inspired by Hashimi’s time in a Soviet-era orphanage, and Sadat folds her subject into this dramatisation further by casting Hashimi as the facility’s supervisor, Anwar. Unlike, say, François Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) or Tsai Ming-liang’s Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng) – recurring characters who serve as on-screen alter egos for their auteurs – Qodrat continues to be employed by Sadat in her chronicles of Hashimi’s life because his experiences suggest something beyond the individual. ‘Through his personal story,’ she offers, ‘you read the history of Afghanistan’.[8]ibid.

Though seeking to portray Afghanistan, Sadat shot both of her films – for safety reasons, especially given her crew are predominantly female – in neighbouring Tajikistan. Each production was a logistical minefield. For Wolf and Sheep, the entire cast of villagers had to travel from remote central Afghanistan (which most had never left previously), through a Taliban stronghold in the mountains, to Kabul, from where they could covertly travel to Tajikistan, which has restrictions on Afghans coming into the country. In Tajikistan’s own rural mountains, the crew built a replica of an Afghan village. In turn, while making The Orphanage, Sadat felt as if she was ‘working for a travel agency: preparing ID cards, passports, visas for Tajikistan, and visas for Pakistan’,[9]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Gabriela Rico, ‘Cannes 2019 Women Directors: Meet Shahrbanoo Sadat – The Orphanage’, Women and Hollywood, 17 May 2019, <https://womenandhollywood.com/cannes-2019-women-directors-meet-shahrbanoo-sadat-the-orphanage/>, accessed 4 November 2019. and visa issues partly contributed to why the cast ended up largely male.[10]Schiefer, op. cit., p. 4.

Qodrat continues to be employed by Sadat in her chronicles of Hashimi’s life because his experiences suggest something beyond the individual. ‘Through his personal story,’ she offers, ‘you read the history of Afghanistan’.

Sadat cast both films herself, and each is filled with non-actors, predominantly children. ‘The characters in Wolf and Sheep are real, but they play in the film; in The Orphanage, they act,’ she reflects.[11]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Jan Lumholdt, ‘Shahrbanoo Sadat • Director of The Orphanage’, Cineuropa, 22 May 2019, <https://cineuropa.org/en/interview/373022/>, accessed 4 November 2019, emphasis in original. In shooting her solo debut feature, Sadat presented her young subjects with parameters, and had them play out scenarios rather than work from scripts: ‘They are kids and they want to have fun and if they are bored or their mood is off, they will destroy the scene.’[12]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in ‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, op. cit. In certain scenes, we see these children literally play-acting: boys pretending to be soldiers, fighting; girls ‘bartering’ over the price of imaginary sheep or brides or dung (which, used as fuel, is central to local currency/status). They swear, they smoke mock cigarettes, they gossip – acting as adults do. Gossip eventually turns to talk about Sediqa (like Sadat in her own adolescence, an outsider whom no-one trusted) and Qodrat (whose mother is becoming the third wife of a villager); feeling alienated from the small village, these outcasts eventually meet up in the hills, where they become friends as they weave slingshots and steal potatoes together.

Both children and adults recount folktales about the green fairy, a luminous, naked female figure who floats along the hills at night, and the ‘Kashmir Wolf’, a shapeshifting creature that walks on two legs and hunts villagers and their sheep. While most of Wolf and Sheep works in observationalist vérité, watching the daily rituals of non-actors, discrete sequences literalise local superstitions and belief as these figures are brought to life (both played by Patricia Alexandra Aparicio Dias) with due lyricism. ‘[Afghan] stories are a mixture of fantasy, wishes, lies, fiction and everyday life,’ Sadat says. ‘Oral stories are the best material to learn about communities […] People come to believe stories that have been made up. Our history has been influenced by stories that mix reality and the fantasy’.[13]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Simon Foster, ‘Wolf and Sheep: The Shahrbanoo Sadat Interview’, Screen-Space, 25 May 2017, <http://screen-space.squarespace.com/features/2017/5/25/wolf-and-sheep-the-shahrbanoo-sadat-interview.html>, accessed 4 November 2019.

Like so many folktales, these stories are told partly to keep children in line: the fairy is a symbol of the perils of female sexuality; the Wolf, an ever-present danger, a spectre that will get those who dare to stray from convention. ‘We are told that if you choose your own way, there is the danger of “the wolf,” which scares us even though none of us have seen [it],’ Sadat asserts.[14]ibid. This recalls the film’s title and broader ideas. Village life, in Sadat’s experience, was bound by superstition, conformism and isolation. The treacherous mountain landscape meant that each community was separated from its neighbours, becoming its own microcosm. All of these themes speak to how Wolf and Sheep – which ends, notably, with the whole village relocating out of fear of the Wolf – offers an indictment of Afghanistan. ‘I see the Afghan community as a flock of sheep, all going together in one direction,’ Sadat declares. ‘This society is so poisoned […] The price of being accepted by this community is giving up on individual thought and just thinking like everyone else.’[15]Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Alex King, ‘The Young Filmmaker Defying a Corrupt Movie Industry in Style: Cinema’s Lone Wolf’, Huck, issue 56, July/August 2016, available at <https://www.huckmag.com/art-and-culture/film-2/shahrbanoo-sadat-afghan-filmmaker-interview-wolf-sheep/>, accessed 4 November 2019.

The follow-up to Wolf and Sheep, however, strikes a different note. Most cinematic depictions of orphanages are studies in Dickensian cruelty and abject horror. But, taking her cue from Hashimi’s memories, Sadat’s portrait of a state-run facility actually harbours genuine nostalgia for the era of Soviet rule, a time of prosperity and freedom erased by the emergence of political Islam and the eventual theocratic, dehumanising rule of the Taliban. The Orphanage shows local runaways and orphans being ushered into the establishment, clearly to be trained as loyal young communists and future soldiers. The fact that Fayaz (Ahmad Fayaz Osmani) and Feraji (Masihullah Feraji) – who are part of the same ‘intake’ as Qodrat – are the orphaned sons of Mujahideen rebels only gives them greater rehabilitative potential.

Under the watch of Anwar, Mister Director (Yama Yakmanesh), Miss Deputy Director (Nahid Yakmanesh) and exotic young Russian teacher Miss Petrovna (Daria Gaiduk), the children are given a top-shelf education – complete with mandatory viewing of pro-Soviet newsreels, of course. Whereas early stretches of The Orphanage feel like a prison movie – new inmates starting at the bottom of the abusive social ladder, forced to learn the lay of the land and the rules peculiar to this site of institutionalism – the film stretches out as it goes, finding the joys (and tragedies) of coming of age. Qodrat becomes fast friends with the Diego-Maradona-loving, Argentine-jersey-sporting Hasib (Hasibullah Rasooli), whose only requirement for a potential friend is that they love, and are good at, soccer. Soon, the two are off on misadventures: stealing bikes and apples, swimming in rivers, playing in the shell of a blown-up Russian tank. They join a large cohort flown to Russia for a summer-camp indoctrination (‘You will have a wonderful time here learning the values of our great country’), where they flirt with the opposite sex, take part in a chess tournament (which Feraji wins) and view the late chairman Vladimir Lenin’s preserved body. Much like the contemporaneous documentary Jamilia (Aminatou Echard, 2018), The Orphanage also provides a forum for lamenting how the female experience was ‘better’ under Soviet rule: directing her young cast, Sadat ‘had to explain […] that back then, women wore skirts, showed their hair and could dance’.[16]Sadat, quoted in Lumholdt, op. cit.

Echoing Sadat’s assertion about Hashimi’s life reflecting Afghanistan’s history, the good time in the film soon ends. As is spelt out by the first intertitle, which establishes the film’s setting as 1989, this is a brief interregnum of progressiveness, soon to vanish. ‘Boys, there are some changes in the country,’ says Mr Director to the gathered children late in The Orphanage’s final act. ‘Don’t panic, but it’s possible that the Mujahideen will take Kabul at any moment. For your safety, you should collect all documents relating to the government and the USSR, and gather them in the backyard.’ After a mass burning of all Russian textbooks – history going up in flames – a picture of former USSR general secretary Joseph Stalin is taken off the wall. The pro-Soviet establishment turns pro-Islamist, the genders are separated and, with the withdrawal of Russian funding, the institution soon sinks into squalor. In a final moment of horror, Anwar is executed in cold blood in the street by advancing rebel soldiers.

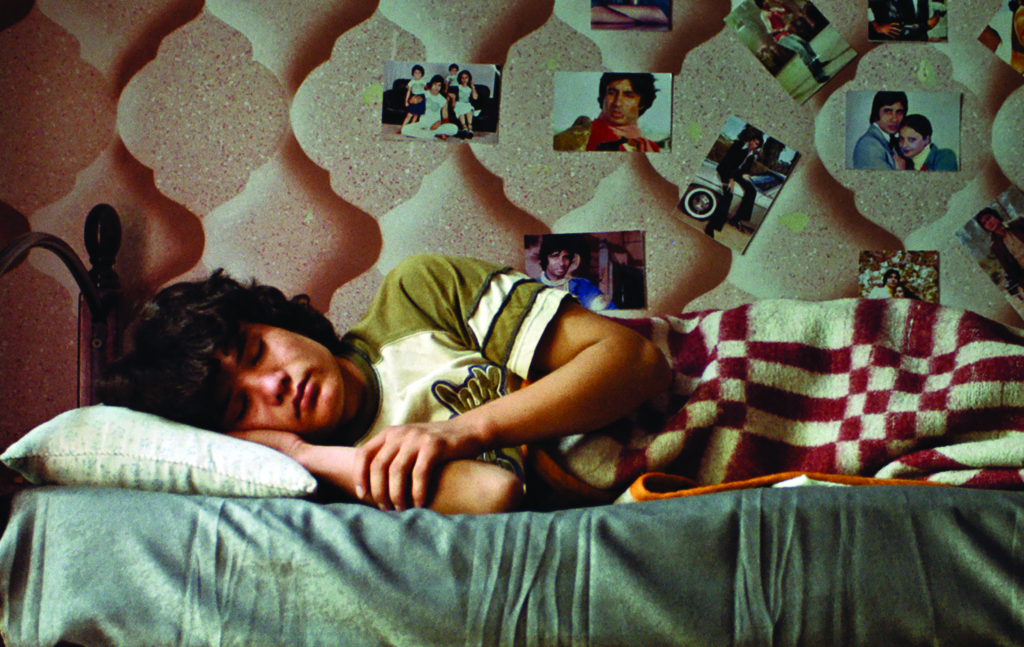

Qodrat seeks safety and reassurance in fantasy. When feeling imprisoned at the orphanage, crushing on a classmate, reeling from the death of Hasib or hoping to fight off the Islamist uprising, he retreats into full-blown Bollywood musical numbers.

In the face of such tragedy, Qodrat – and, in turn, the movie itself – seeks safety and reassurance in fantasy. When feeling imprisoned at the orphanage, crushing on a classmate, reeling from the death of Hasib or hoping to fight off the Islamist uprising, he retreats into full-blown Bollywood musical numbers, set to vintage songs by Kishore Kumar, Lata Mangeshkar, Manna Dey, Kalyanji–Anandji and Asha Bhosle. When we first meet the youngster, he’s scalping tickets outside a Kabul theatre before slipping inside to watch the violent Shahenshah (Tinnu Anand, 1988); this is followed by The Orphanage’s own colourful opening credits, which are set to Bhosle’s banger ‘Jawani Jan-E-Man’, from Namak Halaal (Prakash Mehra, 1982). Sadat’s fantasy sequences are as lurid and romantic as those from their source films: the fight scenes boast the requisite smash zooms, whip pans and surreal ‘punch’ sounds; Qodrat and Sediqa luxuriate in vivid outfits in front of forests and beaches; and Qodrat bids farewell to Hasib while the latter is on a motorcycle journey through the snowy countryside, heading towards the afterlife.

While the evocation of Bollywood summons India’s particular form of cinema, it’s in keeping with the director’s ideas about the centrality of storytelling in Afghan identity, and connects her two most recent films. Just as Wolf and Sheep is a study on the influence of traditional oral storytelling, The Orphanage is a study on the modern-day stories told through cinema and propaganda – these handed-down narratives all having huge influence on how young people view the world. ‘Qodrat daydreams and imagines himself in Bollywood scenes where he lip-syncs the songs in Hindi-Urdu and expresses the feelings he doesn’t dare to voice in his real life,’ Sadat explains.[17]Sadat, quoted in Rico, op. cit. The 1980s saw the height of Bollywood’s influence in Afghanistan; it is a time regarded by bigwigs of the local film industry – following its effective erasure under Taliban rule – as its golden age. Nostalgic for a period ‘when Afghanistan was not an Islamic country and we had art, and we had music, we had cinema’, these industry elders are, according to Sadat, ‘living on that time and they don’t want to get updated or they don’t want to communicate with my generation’.[18]Sadat, quoted in Elphick, op. cit. As a result, she had to make both of her films outside of the system, and outside of the country. And, for all their international acclaim,[19]Sadat’s two most recent films have received nominations from film festivals in Chicago, Munich, Jerusalem, Sydney and elsewhere, with Wolf and Sheep winning the CICAE Art Cinema Award at Cannes in 2016. they’re unlikely to be seen within Afghanistan.[20]See ‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, op. cit.

Sadat is even more dismissive, in interviews, of films made in and about Afghanistan by international filmmakers, mocking their perspective as being wholly shaped by the global media and/or gleaned from Wikipedia. ‘I’m tired of watching and listening to all these clichés,’ she says. ‘International filmmakers are “so concerned” about Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria or comparable countries. What they create concerning these countries is superficial and shallow.’[21]Sadat, quoted in Schiefer, op. cit., p. 3. These works, she reckons, have ‘nothing to do […] with the life of local people’.[22]Sadat, quoted in Elphick, op. cit. Alienated throughout her childhood – first in Iran, then in Afghanistan – and now splitting her time between Copenhagen and Kabul, Sadat remains an outsider hoping to tell her own insider, modern-day ‘folktales’ through film. Undertaking her ambitious pentalogy spun from Hashimi’s diaries, she is out to make a distinctly Afghan cinema. ‘Afghanistan is such a rich country in terms of story,’ she says, ‘and we do need storytellers who can share these stories with the world.’[23]Sadat, quoted in Foster, op. cit.

Endnotes

| 1 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Jeremy Elphick, ‘Wolf and Sheep – an Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat’, 4:3, 17 June 2017, <https://fourthreefilm.com/2017/06/wolf-and-sheep-an-interview-with-shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Tiana Malhotra, ‘Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat / Wolf and Sheep’, Film in Revolt, 19 June 2017, <http://www.filminrevolt.org/shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 3 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Karin Schiefer, ‘Interview with Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Eurimages website, June 2019, p. 1, <https://rm.coe.int/interview-with-shahrbanoo-sadat/1680971c7f>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 4 | See Malhotra, op. cit.; and Taran N Khan, ‘“I Have a Dream and I Want to Fight for It So Hard”: Afghan Director Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Scroll.in, 6 July 2016, <https://scroll.in/reel/811179/i-have-a-dream-and-i-want-to-fight-for-it-so-hard-afghan-director-shahrbanoo-sadat>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 5 | ‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, Raising Films, October 2016, <https://www.raisingfilms.com/interview-shahrbanoo-sadat/>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 6 | Sadat, quoted in Schiefer, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 7 | Sadat, quoted in Malhotra, op. cit. |

| 8 | ibid. |

| 9 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Gabriela Rico, ‘Cannes 2019 Women Directors: Meet Shahrbanoo Sadat – The Orphanage’, Women and Hollywood, 17 May 2019, <https://womenandhollywood.com/cannes-2019-women-directors-meet-shahrbanoo-sadat-the-orphanage/>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 10 | Schiefer, op. cit., p. 4. |

| 11 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Jan Lumholdt, ‘Shahrbanoo Sadat • Director of The Orphanage’, Cineuropa, 22 May 2019, <https://cineuropa.org/en/interview/373022/>, accessed 4 November 2019, emphasis in original. |

| 12 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in ‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, op. cit. |

| 13 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Simon Foster, ‘Wolf and Sheep: The Shahrbanoo Sadat Interview’, Screen-Space, 25 May 2017, <http://screen-space.squarespace.com/features/2017/5/25/wolf-and-sheep-the-shahrbanoo-sadat-interview.html>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 14 | ibid. |

| 15 | Shahrbanoo Sadat, quoted in Alex King, ‘The Young Filmmaker Defying a Corrupt Movie Industry in Style: Cinema’s Lone Wolf’, Huck, issue 56, July/August 2016, available at <https://www.huckmag.com/art-and-culture/film-2/shahrbanoo-sadat-afghan-filmmaker-interview-wolf-sheep/>, accessed 4 November 2019. |

| 16 | Sadat, quoted in Lumholdt, op. cit. |

| 17 | Sadat, quoted in Rico, op. cit. |

| 18 | Sadat, quoted in Elphick, op. cit. |

| 19 | Sadat’s two most recent films have received nominations from film festivals in Chicago, Munich, Jerusalem, Sydney and elsewhere, with Wolf and Sheep winning the CICAE Art Cinema Award at Cannes in 2016. |

| 20 | See ‘Interview: Shahrbanoo Sadat’, op. cit. |

| 21 | Sadat, quoted in Schiefer, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 22 | Sadat, quoted in Elphick, op. cit. |

| 23 | Sadat, quoted in Foster, op. cit. |