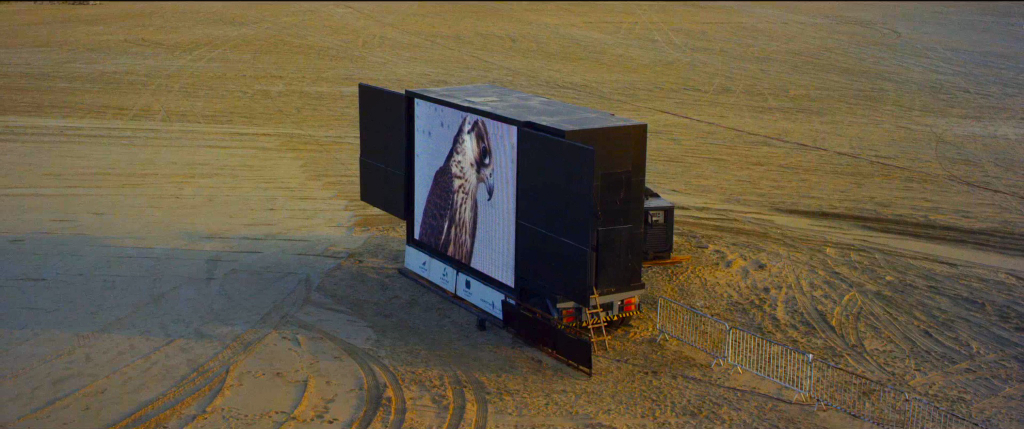

At the beginning of The Challenge (2016), Yuri Ancarani’s film about a falconry tournament in the Qatari desert, we hard-cut from the opening credits to a striking, puzzling image. There, in an otherwise-barren stretch of sand, stands a towering black rectangle, looming in the middle of the frame, in the middle of the desert. It’s a visual evocation of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) that immediately puts the viewers on the back foot. What is this shape? Is it real or a visual effect? What is its purpose, narratively speaking? And what’s it doing in what’s supposed to be a documentary?

‘I could even tell you that the whole film is staged, and that the people you see are actors,’ Ancarani has said, playfully.[1]Yuri Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A | Yuri Ancarani | NDNF17’, YouTube, 1 September 2017, <https://youtu.be/F_I96GTsFRo>, accessed 24 October 2017. The men we see on screen, ridiculously wealthy Arab sheikhs with lives of unimaginable luxury and leisure, could be actors; behind their ghutras and white robes, at least, they’re all interchangeable. The grand vistas of the desert make for such a beautiful background that they could’ve been employed just for visual resonance. And this monolith could be a work of CGI, inserted into the empty expanse to make the alien landscape seem even more alien.

But it’s all real. This towering obelisk, though unexplained in the film, is the work of sculptor Richard Serra; it’s one of a quartet of steel plates standing in the sands of the Brouq Nature Reserve in western Qatar, each mysterious object over 14 metres tall, as part of a work called – notably, here – East-West/West-East.[2]See ‘East-West / West-East by Richard Serra: Sculpture in the Desert’, Qatar Museums website, <http://www.qm.org.qa/en/project/east-west-west-east-richard-serra>, accessed 24 October 2017. The eerie vistas may look like footage brought back from the surface of some barren planet, but the flat-topped, caramel-coloured limestone outcrops, the lifeless sands and the rustling breezes are of this world; if you look carefully, you can make out telephone poles.

And the characters herein – the guy who drives a Lamborghini with a pet cheetah in the passenger seat, the motorcycle-gang leader who rides a 22-karat-gold Harley-Davidson, the falconer who flies his competing birds in a private jet, the motorhead whose souped-up four-wheel drive has a muffler that fires sparks into the sand like wounding gunshots – aren’t fictional creations, but rather, somehow, real people. Even the birds, the most undeniably authentic elements of The Challenge, could’ve been wrangled to tell a director’s story. The collective noun for falcons? A cast.

The Challenge is Ancarani’s first feature film – even if, at sixty-seven minutes long, it only just qualifies. Born in 1972 in Ravenna, the Italian is a video artist whose previous short works have been exhibited in museums and galleries, and are all of a similar spirit: static compositions displaying vivid images, often of the alien landscapes of Earth. His first, Il Capo (co-directed with Pietro Savorelli, 2010), is set in the marble quarries of the Apuan Alps in north-west Italy, its titular character standing atop the quarry – shirtless, skin leathery, face all cracked lines, crucifix nestled among thatch of chest hair – guiding the excavators with hand signals like a maestro conducting a symphony. Piattaforma Luna (2011) dwells with a crew of deep-sea divers in a pod on the ocean floor, appearing, for all the (out of this) world, as if on a space shuttle. Da Vinci (2012) takes us to an unexpected alien landscape: the human body, chronicling the ultra-high-tech, robotic gadgets employed in surgeries. San Siro (2014) is a portrait of Milan’s iconic football stadium, in which the towering structure is seen with an outsider’s gaze – a work of grand-scale architecture unmoored from sporting narrative. And Séance (2014) is literally titled, Ancarani’s stilled camera communing with a medium, the film billed in its trailer as a ‘conversation with Carlo Mollino, architect’ – someone who died in 1973.

The camera in Ancarani’s practice is, indeed, his. There’s no billed cinematographer in The Challenge’s credits (though filming duties were, in fact, shared by Ancarani, Luca Nervegna and Jonathan Ricquebourg[3]Kino Lorber, The Challenge press kit, 2016, p. 5.). All his films are works of visual wonder, but especially this one, whose presentation in the film-festival world has shifted points of reference; it has earned comparisons to the documentaries – Leviathan (Lucien Castaing-Taylor & Véréna Paravel, 2012), Manakamana (Stephanie Spray & Pacho Velez, 2013), The Iron Ministry (JP Sniadecki, 2014) – of Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab.[4]AO Scott, ‘Review: Falcons and Falconers in the Desert of Qatar’, The New York Times, 7 September 2017, <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/movies/review-falcons-and-falconers-in-the-desert-of-qatar.html>, accessed 24 October 2017. In The Challenge, the director says, ‘viewing is fluid and accessible’,[5]Yuri Ancarani, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Kino Lorber, op. cit., p. 3. the documentary an ‘experimental film’[6]Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. told with no enforced narrative, no exposition or explanation, and even little incidental dialogue. Instead, it makes its case with glorious photography and evocative sound design. Ancarani seeks out ‘sublime images’ that find ‘contradictions and place them in conflict with one another, creating short circuits with the intent of having the viewer actively participate in a reflection’.[7]Yuri Ancarani, quoted in Thom Bettridge, ‘Cheetah vs. Lambo: Yuri Ancarani’s Capitalist Mirage’, 032c, 12 December 2016, <https://032c.com/yuri-ancarani>, accessed 24 October 2017.

In The Challenge, that reflection starts immediately. The credits – emblazoned in striking midnight blue, and listed in French, Italian, German and Arabic – play out over a static long shot of a hall filled with countless falcons, flying back and forth. As we watch on, the opening overture by Lorenzo Senni and Francesco Fantini, busy with trilling woodwinds, summons a mood of wonder and movement. This shot is ‘the epitome of the synthesis of the film’, Ancarani says,[8]Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. gazing in wonder at avian majesty – and the grandeur and ambition of the architecture built to house them – but, ultimately, lamenting wild creatures kept in a cage.

From there, we move to the freedom of the open road, where the cheetah-seating Lamborghini hurtles along through the desert like a rocket through space, and a motorcycle gang – in the familiar leather jackets, jeans and sunglasses of classic mid-century American rebellion – take over the entire road, except for when they pull over to the side, lay out mats pointing towards Mecca and pray. There are vast fleets of four-wheel drives, too, ready to scurry all over the sands. All these vehicles are undertaking a pilgrimage to the same place: the land beyond the dunes. It’s the traditional land of the Bedouin, who’ve been practising falconry for millennia. For most of that time, it’s been a practical skill: falcons trained to hunt birds and game for food. Now, it’s become a sport, and one for the wealthy elite.[9]See Sahar Khan, ‘Qatar’s Fascinating Fixation with Falcons’, Paste, 27 July 2017, <https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/07/qatar-falcons-arab-tourism.html>, accessed 24 October 2017. This mirrors Qatar’s own growth: this tiny, barren land – less than a fifth the size of Tasmania – has gone from poverty and obscurity to prosperity and power, becoming the world’s wealthiest country. For the nouveau riche ascending to the Qatari upper class, the pursuit of falconry is an act of status-signalling: arriving in the desert, in whatever blinged-out vehicle they choose, echoing the ostentatiousness of ‘hip-hop culture’.[10]Yuri Ancarani, quoted in DJ Pangburn, ‘Two Words: Qatari Falconry. Two More Words: F*cking Surreal.’, VICE, 12 August 2017, <https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/mbbejp/qatari-falconry-surreal-film-yuri-ancarani>, accessed 24 October 2017.

The presence of such technological blessings foregrounds the theme of tradition meeting modernity … In The Challenge, we are situated at the seemingly contradictory nexus between stern religious devotion, ancient Bedouin custom and fecund, decadent capitalism.

Ancarani’s short films were ‘about the labour of work’, but The Challenge is ‘a film about non-work’.[11]Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. We watch on as affluent men bring the luxuries of home to the middle of nowhere. They set up camp in the dunes, where there’s coffee to be taken, conversations to be had (‘I prefer falconry to camel racing’), a cheetah to be admired, birds to be compared, feasts to be shared (the heart of a lamb the reserved delicacy), FIFA videogames to be played on large flat-screen TVs, funny mobile-phone videos to be made, engines to be revved. Ancarani captures these scenes with meticulous framing, and with composition that seems at once painterly and architectural (a tableau of identical white-clad men sitting on an ornately patterned carpet, in front of a blank white wall dotted only by air-conditioning units, is striking in the way it finds beauty in simplicity).

The presence of such technological blessings foregrounds the theme of tradition meeting modernity, the men bringing the spoils of Doha to the dunes. In The Challenge, we are situated at the seemingly contradictory nexus between stern religious devotion, ancient Bedouin custom and fecund, decadent capitalism. One sheikh takes a phone call to participate in an auction for a peregrine falcon, which he watches via a TV feed. The bird is a beautiful specimen, ‘worth the money’ that it’s going for (‘good wings, good legs, good face’), but he bows out when the bidding escalates, the falcon eventually selling for 87,500 Qatari riyals (around A$30,000).

The result of the auction is attributed, by the men on screen, to God, as are most things in The Challenge. ‘Mashallah’ (subtitled here as ‘God willed it’) is said thirty-four times in sixty-seven minutes, in situations ranging from the banal to the dramatic. The falconry tournament plays out, entirely, as God’s will (the divine long invoked, across the globe, as having an apparent interest in the results of sporting events). But it’s hard to imagine what the divine would think of devout servants staging burnouts in the desert, sending sand flying as they gun their engines and fishtail wildly up and down the dunes.

Ancarani’s approach does, however, hint at the divine, as the documentary draws away from the material and towards the ineffable. Whereas most filmmakers would want to go into this world of dune-driving – chronicling the macho posturing with either a revhead’s approval or an intellectualist’s dismissal – Ancarani pulls back. He shoots the four-wheel drives from on high, gazing down at the balletic curve of their movements, the intuitive expressiveness of off-road, free driving. The tracks they leave behind are shown in God’s-eye view (no less), scrawled like hieroglyphs in the sand. At night, once the men have tended to their engines by the light of their mobile phones, the trucks are still shot from afar. In the nothingness of the desert, we see only their headlights fluttering in the dark like fireflies. An overhead, daytime shot of a fleet of trucks gathered on the edge of a rise evokes birds gathering atop a hill. And there’s an even more direct parallel between birds and technology when some men play with a drone, piloting a mechanical ‘bird’ over the sands.

The Challenge features a recurring motif whereby animal speed and motor speed are contrasted: when the cheetah is inside the car – or the peregrine falcons, the private jet – these creatures, the fastest in the world, inhabit the technology that has outpaced them. But, if the falcons are cooped up for much of the film – hooded, kept indoors, forever tied to a leather glove – in the astonishing final act, we finally see them let loose. After fifty-three minutes drolly observing the human milieu, The Challenge, eventually, arrives at its climax: the falcon becomes the hero of the narrative, and the pigeon, its luckless foil.

Even when this sequence begins, Ancarani doesn’t wholly leap into the competition. First, we witness the sights and sounds of preparation. The sheikhs take their seats on row upon row of golden thrones, set up in front of giant, stadium-scoreboard-size screens laid on the rocky desert floor. The hoi polloi gather in their trucks, ready to chase the action across the sands. The announcer, when not introducing contestants, repeats the emergency contact number for any spectators who might get lost in the desert, and reminds the men driving to be careful, for ‘there are also children in the cars’. One of the birds receives its backstage pre-comp prep: having its feet cleaned, its nails filed with a sander (‘a pedicure’, Ancarani jokes[12]ibid.), its beak buffed with a motorised polisher, the rough edges of its feathers sandpapered away. Even when the action starts, Ancarani takes in the scene: the men watching, the cars milling, the announcer barking. For a film that takes place largely in silence, there’s a sudden run of words: the commentator hollering ‘Go, bird, go!’ repeatedly, full of excitement and desire (‘This falcon is a sparkle,’ he enthuses at one point; hopefully, this delightful turn of phrase is an accurate translation).

But, finally, we are thrown entirely into the fray, taking wing with the falcon itself. Throughout the film, The Challenge has shown glimpses of vision shot by ‘falcon-cam’, a micro camera strapped to the bird of prey’s hood. The images are twitchy, uneasy, moving fast – a contrast to the static compositions that show the men in their leisure. These few early shots have looked at other falcons, at men sitting on carpets, at a snoring cheetah laid out at their feet. Now, though, we watch from the falcon’s perspective mid-flight, mid-tournament. And the results are some of the most beautiful images in cinema history: the bird ascending to godly height, looking down on the tiny figures of men and trucks, the tyre tracks below like crop circles, dust rising heavenward from the ridges of dunes. The bright blue skies around us, we soar over the Earth, the falcon’s own wing in frame when it turns. The pigeon – the goal of this flight – flutters in the periphery. There’s no score, just evocative sound design: distant interjections of engines and wheels the only things encroaching on the beating of wings and the blowing of the wind.

The falcon swoops, the pigeon retreats – these two gladiators in an elemental battle, the results as thrilling as a chariot race. From on high, the falcon dives and the distant ground suddenly thrusts up close, the expanse of monochromatic brown revealing every individual rock as we fly just above the surface. As the falcon presses in, the furious beating of the pigeon’s wings grows louder. This chase engenders a kind of bloodlust in the audience, a yearning for our hero to catch its prey – this, finally, the one moment in which we share the values and desires of the men in this alien world. The film climaxes with the falconry equivalent of a money shot: that moment when the falcon takes down the pigeon, delivers the death in this avian snuff movie. The flying abruptly ends as we hit the ground, the hunter looking down at its feet, squashing its victim, the pigeon now a mess of torn feathers and blood. The final images are of the sandals of men entering the frame, this visual eventually lost in a disorienting kaleidoscope of sand and stone; the credits, thereafter, roll accompanied only by the ambient sounds of the desert.

This is ‘the challenge’ of the title: falcon versus pigeon, a battle as old as time itself. But it’s not the sole battle, the film chronicling an oft-absurd microworld in which there are collisions between East and West, religion and capitalism, community and individuality, repression and freedom, tradition and modernity, physicality and technology, animal and machine. These are themes both specific to Qatar and broadly universal, Ancarani’s ‘experimental’ documentary a widely accessible work of clear theme and photographic wonder: a visionary film whose surreal scenes have to be seen to be believed.

Endnotes

| 1 | Yuri Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A | Yuri Ancarani | NDNF17’, YouTube, 1 September 2017, <https://youtu.be/F_I96GTsFRo>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | See ‘East-West / West-East by Richard Serra: Sculpture in the Desert’, Qatar Museums website, <http://www.qm.org.qa/en/project/east-west-west-east-richard-serra>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

| 3 | Kino Lorber, The Challenge press kit, 2016, p. 5. |

| 4 | AO Scott, ‘Review: Falcons and Falconers in the Desert of Qatar’, The New York Times, 7 September 2017, <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/movies/review-falcons-and-falconers-in-the-desert-of-qatar.html>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

| 5 | Yuri Ancarani, ‘Director’s Statement’, in Kino Lorber, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 6 | Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. |

| 7 | Yuri Ancarani, quoted in Thom Bettridge, ‘Cheetah vs. Lambo: Yuri Ancarani’s Capitalist Mirage’, 032c, 12 December 2016, <https://032c.com/yuri-ancarani>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

| 8 | Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. |

| 9 | See Sahar Khan, ‘Qatar’s Fascinating Fixation with Falcons’, Paste, 27 July 2017, <https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2017/07/qatar-falcons-arab-tourism.html>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

| 10 | Yuri Ancarani, quoted in DJ Pangburn, ‘Two Words: Qatari Falconry. Two More Words: F*cking Surreal.’, VICE, 12 August 2017, <https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/mbbejp/qatari-falconry-surreal-film-yuri-ancarani>, accessed 24 October 2017. |

| 11 | Ancarani, in ‘The Challenge Q&A’, op. cit. |

| 12 | ibid. |