Australian Survivor has graced the pages of Metro before. Back in 2018, scholar Stuart Richards examined his dissatisfaction with the show’s first season[1]‘First season’ is more contentious than you might think. Wikipedia lists the 2016 season of Australian Survivor – the first produced by Network Ten – as ‘Season 3’, and many pedants online do the same, arguing that it should be considered congruent with the preceding (and undeniably unsuccessful) early 2000s series filmed by Nine and Seven respectively. I don’t put much stock in this approach, and will begin my numbering from 2016 for the purposes of this piece. See ‘Australian Survivor (Season 3)’, Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Survivor_(season_3)>, accessed 10 August 2020. through the lens of how the US series and its ‘paratextual media’[2]Stuart Richards, ‘Swapping Goats for Snakes: Australian Survivor, Narrative Complexity and Audience Expectations’, Metro,no. 195, 2018, p. 59. have manifested across its two decades of history.[3]To clarify, the twentieth anniversary of the US iteration of Survivor – itself technically an adaptation of the mostly forgotten Swedish series Expedition Robinson – was celebrated on 31 May 2020. Richards is unmistakably a huge fan of Survivor, and I don’t disagree with his misgivings surrounding the Australian version’s shaky first steps. But, as someone who became a fan of the format thanks to Australian Survivor’s subsequent, far more successful seasons, I think our local series warrants re-evaluation.

One of Richards’ arguments was that the adaptation suffered from trying to appeal to ‘fans of the original series […] without alienating a wider viewership who may be unfamiliar with the strategic complexities of the format’.[4]Richards, op. cit., p. 54. That challenge has been eroded with each subsequent season; thanks to an established audience, the four seasons that followed the first have had more freedom to draw upon viewer familiarity and shorthand. This came to a head in the fifth season, 2020’s Australian Survivor: All Stars, which featured a cast entirely composed of returning players and a narrative arc heavily reliant on references to the events of earlier seasons.

I would argue that this shift has paid dividends – yes, in terms of entertainment value. But it’s also evidenced by the show’s ratings. Though the number of viewers dipped somewhat for the show’s second and third seasons, both Season 4 and All Stars cracked a million viewers for their finales.[5]See James Manning, ‘TV Ratings September 17: Survivor Finale Edges over 1m as Pia Wins Hearts & Dollars’, Mediaweek,18 September 2019, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/tv-ratings-september-17-2019/>; and Hannah Blackiston, ‘878,000 Metro Viewers Tune In for the Finale of Australian Survivor: All Stars with the Winner Announcement Pushing Close to 1m’, Mumbrella, 31 March 2020, <https://mumbrella.com.au/878000-metro-viewers-tune-in-for-the-finale-of-australian-survivor-all-stars-with-the-winner-announcement-pushing-close-to-1m-623098>, both accessed 5 August 2020. As Mediaweek put it, discussing Season 4, ‘In the important advertising demographics, Australian Survivor was a challenge beast and across its run was the #1 show in under 50s and all key demos.’[6]James Manning, ‘TV Ratings Guide: Australian Survivor 2019’, Mediaweek,18 September 2019, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/tv-ratings-guide-australian-survivor-2019/>, accessed 5 August 2020. This growth went hand in hand with critical acclaim; for instance, Inside Survivor described the second season as a ‘Cagayan level masterpiece’, referring to the US show’s well-regarded twenty-eighth season.[7]Andy Pfeiffer, ‘Historical Perspectives: Don’t Vote Me Out’, Inside Survivor,28 March 2018, <https://insidesurvivor.com/historical-perspectives-dont-vote-me-out-32886>, accessed 5 August 2020.

That growth in audience numbers can be credited, at least in part, to clever production decisions designed to attract audiences who either aren’t familiar with the US series or were put off by the dramatic inertia of the first season’s final stretch of episodes. Both the third and fourth seasons of the show were subtitled ‘Champions v Contenders’, recruiting a range of recognisable celebrities[8]Of, it must be said, varying degrees of celebrity. to compete against ‘everyday Aussies’. The presence of notable athletes (including swimmer Shane Gould, who won her season), famous actors (including Pia Miranda, who won her season) and even an infamous US Survivor contestant (Russell Hantz, who was the first voted out from the Champions tribe in the third season) would surely have helped to attract new sets of eyes to the show.

Ah, but the real challenge is holding on to these viewers. Putting Australian Survivor and its US counterpart side by side is illuminating. Compared to modern Survivor, the Australian adaptation seems like a slicker product in many respects. By ‘slicker’, I’m referring to production values, though you could argue that Australian Survivor is overproduced[9]And many have! All Stars,in particular, was plagued by complaints online about its editing, with many fans claiming that the winner was obvious from early on in the season due to the producers’ editing and marketing decisions. See, for example, Austin Smith, ‘Australian Survivor All-Stars Episode 15 Recap – I Scream, You Scream’, Inside Survivor, 4 March 2020, <https://insidesurvivor.com/australian-survivor-all-stars-episode-15-recap-i-scream-you-scream-43017>, accessed 10 August 2020. – its longer episodes, lavishly produced title sequence[10]With its thirty-ninth season, the American Survivor series stopped producing title sequences entirely. See Ari Bacher, ‘In Support of the Survivor Title Sequence’, Inside Survivor, 9 October 2019, <https://insidesurvivor.com/support-survivor-title-sequence-40479>, accessed 10 August 2020. and soaring score result in a show that can be gripping even when … well, not a whole lot is happening.

Though this is frequently obfuscated by the edit, Australian Survivor is generally a less eventful show than its originator. That can be credited to the contestants involved, to a degree. Certainly, Season 1 suffered from selecting contestants like Sam Webb, whose subsequent casting on Home and Away gives some insight into his motivation for signing up to the show. And one could (and I will!) consider the cultural differences between Australians and Americans in the context of reality TV.

But really, what defines the dramatic arc of Australian Survivor – where quieter, subtler players are typically rewarded and the ‘big moves’ so beloved of US series host Jeff Probst tend to be met with immediate eliminations – is its broader structure. Instead of sixteen to twenty players, twenty-four compete. There are fifty-odd[11]Fifty-five in the first two seasons, filmed in Samoa, and then fifty in the following, Fiji-set, seasons days rather than thirty-nine. A season of US Survivor typically features around a dozen episodes; Australian Survivor, to accommodate Network 10’s reality-show rotation, invariably stretches to an even twenty-four. The biggest difference, to my eye, is the prize structure:[12]There are plenty of other differences, of course; increasingly, the American Survivor series have been set up to favour a certain kind of player, with changes to the final couple of votes protecting the ‘bigger’ players that fans (and, allegedly, Probst) prefer. Australian Survivor maintains the traditional two-person final tribal council, though rumours abound that there would have been a top three in All Stars had it not been for Lee Carseldine’s unforeseen exit from the show for family reasons. though both series boast a hefty prize for first place (US$1 million in the States, half-a-million Australian dollars over here[13]Which isn’t as big of a disparity as it sounds, given that prizes are taxed in the US but not over here. It’s also worth noting, for accuracy’s sake, that the most recent season of Survivor, Winners at War, had double the usual prize for first place.), the sliding scale in the States rewards players with five- and six-figure sums for making it to the end. Though there’s surely money set aside for appearance fees at the reunion et al., there isn’t a single dollar for placing below first in Australian Survivor.[14]As confirmed by Baden Gilbert, runner-up in Season 4, in his October 2019 Reddit AMA: ‘Only first place gets prize money here […] I guess it makes your [sic] hungrier for the win instead of settling for a lower position, but I still reckon there should be a prize ladder.’ Gilbert, in ‘Baden Gilbert AMA’, Reddit <https://www.reddit.com/r/survivor/comments/d7334f/baden_gilbert_ama/>, accessed 10 August 2020.

Where a player might have a legitimate aim of riding a strong player’s coat-tails to the tune of tens of thousands of US dollars in the States (the ‘goat’ strategy), that’s entirely discouraged by Australian Survivor – meaning that the aggressive, bombastic players tend to be cut off at the knees, so to speak, before reaching the show’s endgame. With one notable exception, the five winners of Australian Survivor to date have played relatively below-the-radar games that, while clearly strategically successful, must have proven challenging for television producers.

The American seasons of Survivor tend to offer a comparatively equitable edit, spreading the attention across the contestants relatively evenly. Naturally, some participants are favoured[15]As Hantz was in the nineteenth season, Samoa. and others are (nearly) ignored,[16]The most infamous example being ‘Purple’ Kelly Shinn in Survivor: Nicaragua. but the tendency for winners to play ‘bigger’ games in the States allows the editors to let their games speak for themselves, meaning that the journey of the winner – overcoming obstacles, defeating villains, etc. – seems to come together relatively organically. Trying the same approach with Australian Survivor’s first season proved ineffective: though Kristie Bennett’s winning game was capped with an impressive final tribal-council speech, her low-key play (and the sprawling cast) meant she was a nonentity for much of the season. Instead, the editors often focused on the contestants on the figurative chopping block, making for a whiplash-inducing roller-coaster as sympathy was swiftly accumulated for characters … who were just as swiftly eliminated.

Australian Survivor’s subsequent seasons took a slightly different tack. With the exception of All Stars, the winners haven’t been heavily featured. But that isn’t to say they’re ignored. A mere two episodes in to Season 4, Inside Survivor correctly pegged Miranda’s ‘winning edit’[17]Fenella McGowan, quoted in Martin Holmes, ‘Australian Survivor 2019 Power Rankings (Round 1)’, Inside Survivor,28 July 2019, <https://insidesurvivor.com/power-rankings/australian-survivor-2019-power-rankings-round-1>, accessed 10 August 2020. thanks to the breadcrumbs the producers were leaving to engage audiences in her story arc. By and large, however, the editors have opted to offer a more heavily produced narrative than their American counterparts, focusing considerably more on some characters and their antics at the expense of others, and making choices – such as not giving some players any confessionals, either early (in the case of Benji Wilson) or altogether (for Sam Schoers) – that tend to disorient show devotees familiar with the rhythms of the American original.

There’s no better exemplar of this than Luke Toki. First appearing in Season 2, Toki’s mischief-making – like changing an early vote seemingly for comedy rather than strategy – quickly cemented him as the kind of larrikin character beloved of Australian audiences, and the edit showcased his antics accordingly. Toki was a major figure in his first appearance; though he was eliminated seventh, one of his key allies, Jericho Malabonga, went on to win the season. His return in Season 4 solidified both his significance to the game and the increasing cultural import of Australian Survivor locally. Toki was established as the quick-witted protagonist of the season, with his inevitable elimination in the top four accompanied by the kind of manipulative music you’d never get in the States. Shortly thereafter, a fan-made GoFundMe campaign raised A$500,000 for him – equivalent to the season’s prize money – and demonstrated more effectively than any ratings numbers the popularity of the show.

What defines the dramatic arc of Australian Survivor – where quieter, subtler players are typically rewarded and the ‘big moves’ so beloved of US series host Jeff Probst tend to be met with immediate eliminations – is its broader structure.

Players like Toki demonstrate that, more than ever, Australian reality-television participants are savvier to the intricacies of the industry. That’s true in the simple sense that, since Season 1, the majority of Australian Survivor contestants have evinced some familiarity with the Survivor format and its history. Richards’ 2018 article asserted that ‘a significant proportion of Australian contestants have themselves been unfamiliar with the American series, with many expressing discomfort about the “backstabbing” aspect of the game’.[18]Richards, op. cit., p. 58. Though a defensible claim for Season 1, we’ve since seen returning players (Hantz, Toki and of course the entirety of the All Stars cast) and frequent allusions to the legacy of the American show. For instance, contestant Shaun Hampson argued for Toki’s elimination in the fifteenth episode of Season 4 by referring to players with similar stories invariably winning, and Miranda defended her tactics at the same season’s tribal council by underlining the difference between the required play styles across the two versions of the show.

But the contestants’ reality-show literacy goes beyond Survivor specifically. For a long time, I’ve felt that Australian and American reality shows can be generally distinguished by our emphasis on authenticity – or, at least, a perceived authenticity – in stark contrast to the more performative affect of participants in American reality TV. I’m not sure that’s true anymore, and recent seasons of Australian Survivor provide plenty of examples of why.

Toki has undeniably profited hugely from his appearances – that GoFundMe sum, an advertising campaign, a co-hosting role on Talking Tribal – without winning a cent in the show itself. By recognising the value of personality (and, I’d argue, consciously playing up to the camera), he was able to leverage his casting into significant success without, critically, needing to necessarily succeed at the game. Maybe Toki just happens to be a likeable guy. But he’s representative of so much of the modern Australian reality-show landscape, where those cast hope to leverage their fifteen minutes of fame into something more substantial.

Which seems as a good a time as any to talk about All Stars. The mere existence of this season – in which two dozen former competitors return to duke it out for half-a-million dollars – is further evidence of the evolution of Australian Survivor from a show of would-be soap stars and ex-athletes to one featuring well-informed, strategic competitors.[19]Granted, said competitors also incorporate would-be soap stars and more than a few ex-athletes. But this time they (mostly) know how to play Survivor. More specifically, though, the story of David Genat, an eliminated ally of Toki’s in Season 4 who went on to win All Stars, encapsulates the light years of difference between the first and fifth seasons of the show.

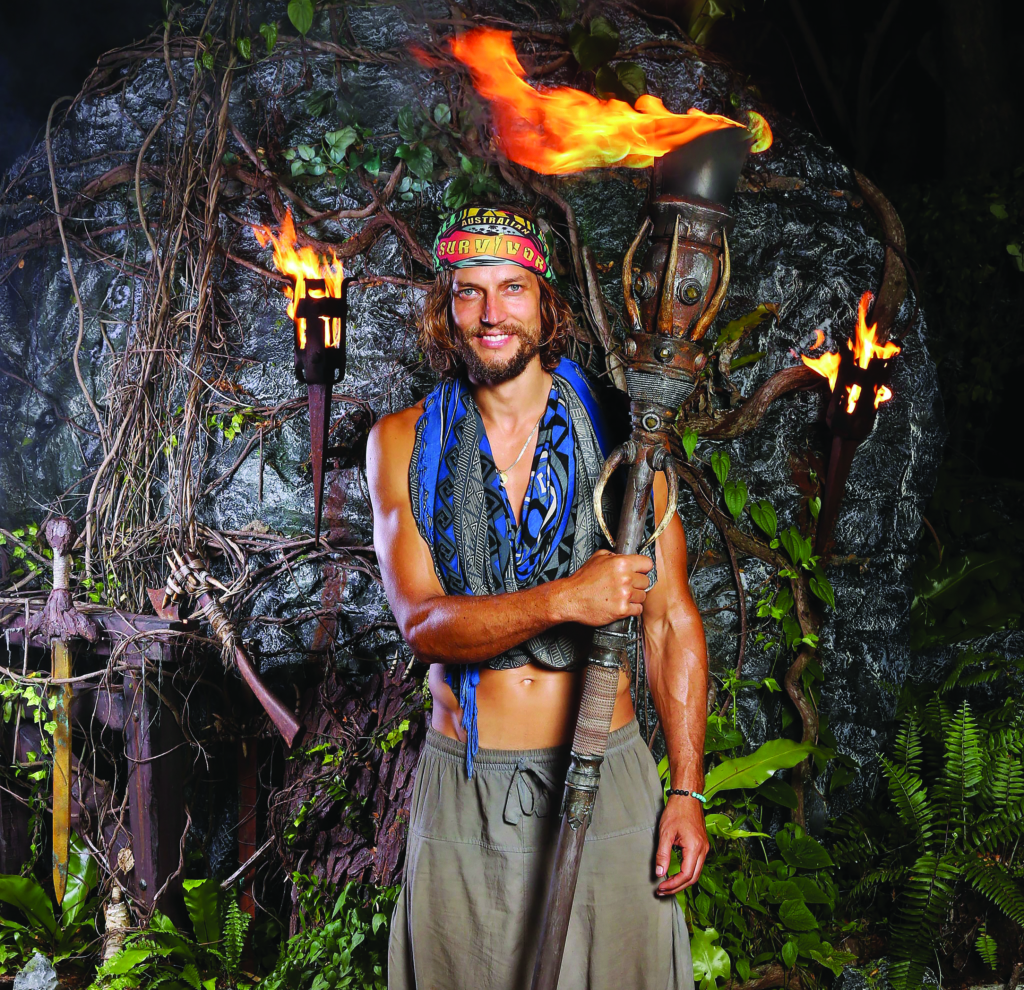

Genat is an archetypal self-aware reality-show contestant: attractive, charismatic and possessed of a larger-than-life personality. Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his background (as a professional model based, until recently, in New York), he’s incredibly comfortable in front of the camera, delivering outsized performances that are as artificial as they are entertaining. While Genat’s win was built on the same principles of most Survivor successes – a combination of smart alliances, social strategy and a dash of athletic talent – it was paired with an irrepressible urge to amuse audiences at home. Even if he hadn’t managed to win on his second attempt, it’s hard to imagine him not being able to pivot his personality on the show into some kind of media endeavour.

That’s always been the case with Australian reality television, to a degree. Think media personalities like Ryan ‘Fitzy’ Fitzgerald or Sam Frost, who turned their time in the spotlight (on Big Brother and the Australian editions of The Bachelor/Bachelorette, respectively) into full-time entertainment careers. But more and more, reality television in Australia is becoming an interconnected marketplace, in stark contrast to Richards’ assertion a couple of years ago:

Australian Survivor [embodies] a considerable challenge for Australia’s media ecology. Network Ten’s other reality shows rarely generate the type of narrative complexity that requires the audience to engage in any memory recall.[20]Richards, op. cit., p. 59.

That kind of memory recall is integral to so much modern reality television. Cooking shows from My Kitchen Rules to MasterChef Australia have recently screened seasons showcasing previous competitors, leveraging audiences’ existing connections to their favourite (or least favourite) contestants. The Australian Bachelor franchise has, like its American counterpart, become a revolving door of attractive young things who cycle through seasons vying for or handing out those all-important roses. These ecosystems aren’t hermetically sealed, either. Angie Kent turned her casting on Gogglebox Australia into a marathon of reality television: first I’m a Celebrity… Get Me Out of Here!, then The Bachelorette Australia and, this year, Dancing with the Stars. Australian Survivor contestants can be counted among this number, whether it’s Aimee Stanton popping up on House Rules or Locky Gilbert – from Seasons 2 and 5 – being named as the next star of the Australian Bachelor.

What sunk the first season of Australian Survivor was how its island setting bled into production choices. As Richards identified, the show felt isolated from its decades of history, with too many contestants stumbling through what’s intended to be a strategic show with the barest modicum of strategy. Not anymore. Thanks to clever casting and the show’s increasing cultural prominence, contemporary Australian Survivor is filled with contestants who know exactly what they’re getting into. Whether that means they’ll carefully strategise to win the cash prize or mug for the camera to leverage a media career is another question altogether.

Endnotes

| 1 | ‘First season’ is more contentious than you might think. Wikipedia lists the 2016 season of Australian Survivor – the first produced by Network Ten – as ‘Season 3’, and many pedants online do the same, arguing that it should be considered congruent with the preceding (and undeniably unsuccessful) early 2000s series filmed by Nine and Seven respectively. I don’t put much stock in this approach, and will begin my numbering from 2016 for the purposes of this piece. See ‘Australian Survivor (Season 3)’, Wikipedia, <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Survivor_(season_3)>, accessed 10 August 2020. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Stuart Richards, ‘Swapping Goats for Snakes: Australian Survivor, Narrative Complexity and Audience Expectations’, Metro,no. 195, 2018, p. 59. |

| 3 | To clarify, the twentieth anniversary of the US iteration of Survivor – itself technically an adaptation of the mostly forgotten Swedish series Expedition Robinson – was celebrated on 31 May 2020. |

| 4 | Richards, op. cit., p. 54. |

| 5 | See James Manning, ‘TV Ratings September 17: Survivor Finale Edges over 1m as Pia Wins Hearts & Dollars’, Mediaweek,18 September 2019, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/tv-ratings-september-17-2019/>; and Hannah Blackiston, ‘878,000 Metro Viewers Tune In for the Finale of Australian Survivor: All Stars with the Winner Announcement Pushing Close to 1m’, Mumbrella, 31 March 2020, <https://mumbrella.com.au/878000-metro-viewers-tune-in-for-the-finale-of-australian-survivor-all-stars-with-the-winner-announcement-pushing-close-to-1m-623098>, both accessed 5 August 2020. |

| 6 | James Manning, ‘TV Ratings Guide: Australian Survivor 2019’, Mediaweek,18 September 2019, <https://www.mediaweek.com.au/tv-ratings-guide-australian-survivor-2019/>, accessed 5 August 2020. |

| 7 | Andy Pfeiffer, ‘Historical Perspectives: Don’t Vote Me Out’, Inside Survivor,28 March 2018, <https://insidesurvivor.com/historical-perspectives-dont-vote-me-out-32886>, accessed 5 August 2020. |

| 8 | Of, it must be said, varying degrees of celebrity. |

| 9 | And many have! All Stars,in particular, was plagued by complaints online about its editing, with many fans claiming that the winner was obvious from early on in the season due to the producers’ editing and marketing decisions. See, for example, Austin Smith, ‘Australian Survivor All-Stars Episode 15 Recap – I Scream, You Scream’, Inside Survivor, 4 March 2020, <https://insidesurvivor.com/australian-survivor-all-stars-episode-15-recap-i-scream-you-scream-43017>, accessed 10 August 2020. |

| 10 | With its thirty-ninth season, the American Survivor series stopped producing title sequences entirely. See Ari Bacher, ‘In Support of the Survivor Title Sequence’, Inside Survivor, 9 October 2019, <https://insidesurvivor.com/support-survivor-title-sequence-40479>, accessed 10 August 2020. |

| 11 | Fifty-five in the first two seasons, filmed in Samoa, and then fifty in the following, Fiji-set, seasons |

| 12 | There are plenty of other differences, of course; increasingly, the American Survivor series have been set up to favour a certain kind of player, with changes to the final couple of votes protecting the ‘bigger’ players that fans (and, allegedly, Probst) prefer. Australian Survivor maintains the traditional two-person final tribal council, though rumours abound that there would have been a top three in All Stars had it not been for Lee Carseldine’s unforeseen exit from the show for family reasons. |

| 13 | Which isn’t as big of a disparity as it sounds, given that prizes are taxed in the US but not over here. It’s also worth noting, for accuracy’s sake, that the most recent season of Survivor, Winners at War, had double the usual prize for first place. |

| 14 | As confirmed by Baden Gilbert, runner-up in Season 4, in his October 2019 Reddit AMA: ‘Only first place gets prize money here […] I guess it makes your [sic] hungrier for the win instead of settling for a lower position, but I still reckon there should be a prize ladder.’ Gilbert, in ‘Baden Gilbert AMA’, Reddit <https://www.reddit.com/r/survivor/comments/d7334f/baden_gilbert_ama/>, accessed 10 August 2020. |

| 15 | As Hantz was in the nineteenth season, Samoa. |

| 16 | The most infamous example being ‘Purple’ Kelly Shinn in Survivor: Nicaragua. |

| 17 | Fenella McGowan, quoted in Martin Holmes, ‘Australian Survivor 2019 Power Rankings (Round 1)’, Inside Survivor,28 July 2019, <https://insidesurvivor.com/power-rankings/australian-survivor-2019-power-rankings-round-1>, accessed 10 August 2020. |

| 18 | Richards, op. cit., p. 58. |

| 19 | Granted, said competitors also incorporate would-be soap stars and more than a few ex-athletes. But this time they (mostly) know how to play Survivor. |

| 20 | Richards, op. cit., p. 59. |