Australia didn’t enter into any international co-productions until 1986, when we signed a memorandum of understanding with France;[1]See Screen Australia, Friends with Benefits: A Report on Australia’s International Co-production Program, 2012, p. 3, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/0bba5988-c027-4393-9d9c-458d531c5998/Friends-with-benefits-report-copy.pdf>, accessed 6 November 2017. this makes our film industry a very late bloomer compared to others across the world. As our burgeoning industry started to catch the world’s gaze during our golden era in the 1970s and 1980s, creatives overseas displayed a keen interest in working with Australians. Equally, when Australian filmmakers – such as Jan Chapman, Peter Weir, Jane Campion, Bruce Beresford and Phillip Noyce – became successful, they started to look for opportunities further afield. While some went to Hollywood, others sought to continue telling Australian stories – albeit with bigger budgets and greater access to foreign markets.

Yet co-productions haven’t always caught fire in this country. For every success like UK–Australian–US title Lion (Garth Davis, 2016) – which, as of March 2017, had taken an astonishing A$127.3 million outside Australia and A$27 million domestically[2]Sandy George & Bernadette Rheinberger, ‘Part 2: International Performance’, in ‘94 Films: A Commercial Analysis’, Screen Australia website, 15 March 2017, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2017/02-28-94-films-a-commercial-analysis/part-2-international-performance>, accessed 6 November 2017. – there have been many others that didn’t take off, like Christopher Smith’s Melissa George vehicle Triangle (2009), a co-production with the UK that cost US$12 million to make but returned only US$1.6 million worldwide.[3]‘Triangle (2010)’, The Numbers, <http://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Triangle-(2009)#tab=summary>, accessed 6 November 2017.

Nonetheless, Screen Australia head of producer offset and co-production Tim Phillips is complimentary about such partnerships: ‘International co-productions give Australian filmmakers a shot at two markets, which they wouldn’t normally get domestically.’ Indeed, co-productions offer many advantages: a larger audience pool that the film can reap profits from, more substantive budgets and bigger crews. Put simply, they offer strength in numbers – a filmmaker has double the firepower and double the targets. By their very nature, co-productions immediately look outwards to the rest of the world, and so their content will reflect this. This means they are better set up to attain a global reach compared to a typical Aussie feature that may do well domestically but subsequently has to rethink and drastically rebrand in order to be competitive in foreign markets.

Traditionally, Australia’s domestic market has been tough for filmmakers. We have a shrinking government-funding pool – be it from state or federal agencies – and audiences for local fare have also drastically dropped off, especially in certain demographics.[4]See Karl Quinn, ‘Why Won’t We Watch Australian Films?’, The Age, 26 October 2014, <http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/why-wont-we-watch-australian-films-20141024-11bhia.html>, accessed 6 November 2017. And any Australian film that does find its way to the big screen must then compete with huge blockbusters bolstered by Hollywood’s massive marketing machine, which rides roughshod over any local product.[5]See Steve Dow, ‘What’s Wrong with Australian Cinema?’, The Guardian, 26 October 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/oct/26/australian-film-australian-audiences>, accessed 6 November 2017.

‘You need the project to creatively suit a co-production structure … Whether it’s the locations, the technical expertise, or cast or other creative elements, a co-production needs to organically make sense – not be something that’s forced.’

—Todd Fellman

In light of all of this, international co-productions offer a way forward. At the time of writing, there have been sixty-two co-produced Australian features made since 1986, with a combined budget investment of A$765 million.[6]Screen Australia, ‘Statistics by Type of Production’, in ‘Co-production Program’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/co-production-program/statistics/type-of-production>, accessed 6 November 2017. But just how much of an effective blueprint do they offer for the Australian screen industries?

The power of marketing

Kimble Rendall has been a director on various local and overseas productions for many years. A particularly noteworthy project is the shark thriller Bait 3D (2012), an Australian– Singaporean co-production that received some supplementary funding from China and premiered at the Venice Film Festival. Rendall recounts that, while the film ‘did alright [and] made its money back’, it also ‘wasn’t really promoted [in Australia] – not marketed properly. It was just tossed out. I was a bit down in the dumps about that.’ When the film made its way to China for its theatrical release there, Rendall witnessed an approach to marketing that was much more aggressive and unashamedly more focused on the spectacular:

The Chinese did an amazing marketing campaign – giant shark mouths, video screens with tsunamis, huge studio with the biggest background you’ve ever seen. I’d walk out and fireworks was something we’d never do in Australia. Their emphasis is really on marketing.

He then toured the country after the film’s release and remembers being only onto his third city when he ‘got a text on [his] phone saying, “[Bait 3D] is the number-one film in China. It’s the biggest independent film ever released.”’ The movie proceeded to make US$25 million in China, despite flopping elsewhere.[7]Patrick Frater, ‘Bait 3D Director Kimble Rendall to Stir Up Chinese Co-production The Nest’, Variety, 4 August 2015, <http://variety.com/2015/film/asia/kimble-rendall-to-stir-up-chinese-co-production-the-nest-1201555973/>, accessed 6 November 2017.

Rendall was so inspired by the Chinese reaction to Bait 3D that he went down the co-production path again for his next movie, Guardians of the Tomb (2018; originally titled The Nest). As China is a highly competitive market for the screen sector, a further key advantage of adopting this approach is that films can be released through the country’s normal domestic channels instead of fighting to be one of the thirty-four foreign films allowed in each year.[8]See Jonathan Papish, ‘Foreign Films in China: How Does It Work?’, China Film Insider, 2 March 2017, <http://chinafilminsider.com/foreign-films-in-china-how-does-it-work/>, accessed 6 November 2017.

Double the trouble?

There are downsides to international co-productions as well. Sue Taylor, who worked as producer and executive producer on The Tree (Julie Bertuccelli, 2010), says that co-productions mean extra work, duplication and headache-inducing red tape:

You’re dealing with two separate governments, so it’s double the paperwork (and double the legals!). For The Tree, we had the additional challenge of trying to explain the [Australian] Producer Offset – which was still a fairly new form of tax rebate – and the finance partners on the French side were nervous because they didn’t really understand how it worked. Just to add to our woes, the aftershock from the [global financial crisis] was still being felt, so the exchange rates between the countries was volatile and [made it] very difficult to close all the deals.

Todd Fellman – a producer on Bait 3D and the forthcoming Australian–Chinese title At Last (Yiwei Liu) – echoes these sentiments, citing the fact that co-productions ‘add a whole layer of complexity to the producing side of things. You end up with a lot of overlap in certain areas.’

According to A Few Less Men (Mark Lamprell, 2017) producer Tania Chambers, co-productions are also limited by whether Australia has an existing agreement with the country in question:

The challenge is, without a co-production relationship with territories, it’s difficult to secure funding from that territory. And it’s difficult to tell stories in those places because it’s very difficult to raise finances. I have a project at the moment – Tango Underpants [Miranda & Khrob Edmonds, 2014] – that did well all around in the world. This short film was shot in Buenos Aires. We would like to make the feature [version] in Argentina or Uruguay, but Australia doesn’t have any treaties with Argentina or Uruguay.

In all, however, Taylor contends that out of this sort of adversity can come true collaboration:

It was an incredibly stressful time on both sides but, with hindsight, probably helped forge our partnership. We didn’t really divide up the producer roles [on The Tree], other than the fact that I took greater responsibility for the shoot (because we filmed everything in Australia) and Yaël Fogiel managed the post-production (which was done in Paris).

Lost in translation

What about the day-to-day dealings with a foreign cast or crew? Based on his experiences working in China, Rendall describes co-productions as having ‘a different rhythm’ – though, ultimately, ‘we all speak film language’.

I did use Chinese DOPs, the entire crew was Chinese and we were shooting action sequences through the desert. But it doesn’t matter where they come from: it’s a similar process […] You have things that help you: storyboards, concepts, translators.

Taylor found the cultural differences refreshing:

Working with a French team, I think our filmmaking approaches are a little different, and obviously language changes our understanding and meaning sometimes. From my limited experience, the French tend to take a more ‘organic’ approach to the process, allowing things to happen in unexpected ways, whereas, in Australia, I think we have more of a regimented approach with detailed planning and organisation. I’m not saying one way is better than the other, but they are certainly quite different.

The death of Australian stories?

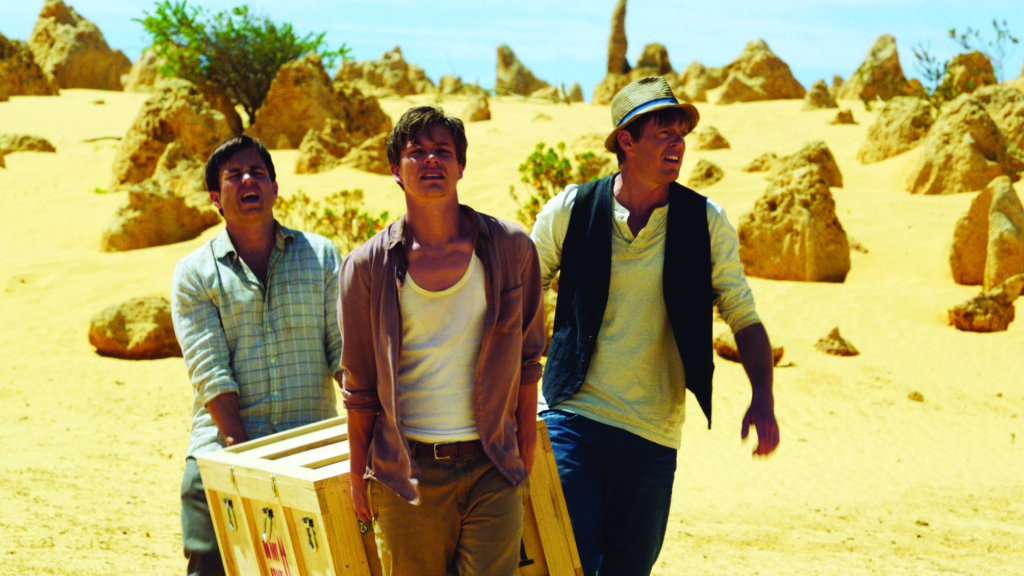

When it comes to Australia’s track record with co-productions, there are arguably two templates for success. The first is to ensure the story is not rooted to a specific culture or place, instead emphasising action and universal experiences. The storyline of Bait 3D, for example, is essentially ‘sharks in a flooded supermarket’; this could be any supermarket, anywhere in the world. Even though it happens to be set in a Singaporean market, with a mostly Australian cast, there’s nothing to particularly stamp it as being of either culture. The second involves the well-worn trope of one culture being seen through the eyes of another. In A Few Less Men, three British best men find themselves stranded in the outback (with a coffin), while At Last revolves around a Chinese couple looking to conceive a baby but falling for a scam in Queensland. Discussing the latter film, Fellman explains, ‘It gives audiences a perspective of Australia but through Chinese eyes [… and] brings those cultures together.’

But does this mean that more conventional Australian stories are being ignored in favour of stories that will resonate in the international marketplace? Will co-productions lead to a homogenisation of Australian storytelling – a loss of the nuances and cultural understanding, in favour of broad stereotypes that will appeal to non-local viewers? Most of the respondents I spoke to thought not.

Phillips argues, ‘I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having a healthy mixed slate of smaller domestic films and bolder, bigger films with an eye to the international market.’ He also makes the point that most local films have an international component, anyway – some Australian filmmakers may choose to shoot components of their work overseas or use international money to finance part of it. A Few Less Men is one such case: Chambers clarifies that the sequel to Australian–British title A Few Best Men (Stephan Elliott, 2011) is an ‘unofficial’ co-production, having received a million dollars in overseas presales despite having no contractual ties to the UK Government.

Chambers also asserts that, when a film is co-produced, stories need not be compromised; however, she does admit that some reworking of the script is inevitable. ‘You have to be careful in the context of both political and cultural sensitivities, and actual language that people understand,’ she says. ‘No-one, for instance, will understand what a “dunny” is, internationally.’ In addition, she points to how co-productions can address ‘an increasing awareness that our screen hasn’t been necessarily representing contemporary Australian culture, with all of its diversity’. In this regard, co-productions may actually tell the e stories of modern Australia better than we realise. By way of illustration, Australian–Indian co-production UnIndian (Anupam Sharma, 2015) depicts interracial relationships and explores the deep cultural connections between Australia and Asia.

Creating for different markets

Rendall openly admits that Guardians of the Tomb was specifically geared for the Chinese market, with Australian audiences only an afterthought: ‘It’s basically aimed at teenage girls in China. That’s the biggest audience in the world.’ But others have opted not to be as deliberate. Regarding the process of creating The Tree, Taylor says the production team just ‘assumed it would work in our respective territories’:

In practice, it worked much better in France than in Australia, though that may have had more to do with the strong response at the Cannes Film Festival. We had a ten-minute standing ovation that barely got reported in Australia but didn’t go unnoticed within the French media.

Chambers, however, disputes the notion that a co-production is ever made for just one market over another:

In order to do a co-production, you have to have an Australian distribution deal in cinema. And, because you’ve got a substantial amount of money from both markets, you are making the movie for both territories.

Moving forward

All things considered, Chambers describes co-productions as ‘a way forward’:

Our talent and ability to access the international marketplace is growing and the demand for our content is growing [… but] we have a limited amount of funds available from state and federal government bodies. So we are increasingly going to be needing the private sector and that international marketplace.

Exemplifying the reach of our films abroad, a Screen Australia report cites that, behind Lion, three of our most lucrative titles based on international performance – Maya the Bee Movie (Alexs Stadermann, 2014), Bait 3D and The Railway Man (Jonathan Teplitzky, 2013) – have all been co-productions.[9]George & Rheinberger, op. cit.

But not all projects are fit for co-production; Fellman cautions that the approach only suits ‘certain types of films’, such as those with larger budgets.

You need the project to creatively suit a co-production structure […] Whether it’s the locations, the technical expertise, or cast or other creative elements, a co-production needs to organically make sense – not be something that’s forced. Otherwise, it results in some kind of inefficiency. You end up trying to produce a film that suits a co-production treaty rather than doing what best serves the script.

Fellman closes by asserting that the ‘financial and logistical elements have to make sense […] It’s a very fine balance between all the creative and financial elements across two different cultures.’

Ultimately, Phillips entreats producers to ‘make sure that the international partner is the right partner for you. Do the due diligence and make sure you’ve both got the same creative vision.’

Endnotes

| 1 | See Screen Australia, Friends with Benefits: A Report on Australia’s International Co-production Program, 2012, p. 3, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/0bba5988-c027-4393-9d9c-458d531c5998/Friends-with-benefits-report-copy.pdf>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Sandy George & Bernadette Rheinberger, ‘Part 2: International Performance’, in ‘94 Films: A Commercial Analysis’, Screen Australia website, 15 March 2017, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/sa/screen-news/2017/02-28-94-films-a-commercial-analysis/part-2-international-performance>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 3 | ‘Triangle (2010)’, The Numbers, <http://www.the-numbers.com/movie/Triangle-(2009)#tab=summary>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 4 | See Karl Quinn, ‘Why Won’t We Watch Australian Films?’, The Age, 26 October 2014, <http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/why-wont-we-watch-australian-films-20141024-11bhia.html>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 5 | See Steve Dow, ‘What’s Wrong with Australian Cinema?’, The Guardian, 26 October 2014, <https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/oct/26/australian-film-australian-audiences>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 6 | Screen Australia, ‘Statistics by Type of Production’, in ‘Co-production Program’, <https://www.screenaustralia.gov.au/funding-and-support/co-production-program/statistics/type-of-production>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 7 | Patrick Frater, ‘Bait 3D Director Kimble Rendall to Stir Up Chinese Co-production The Nest’, Variety, 4 August 2015, <http://variety.com/2015/film/asia/kimble-rendall-to-stir-up-chinese-co-production-the-nest-1201555973/>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 8 | See Jonathan Papish, ‘Foreign Films in China: How Does It Work?’, China Film Insider, 2 March 2017, <http://chinafilminsider.com/foreign-films-in-china-how-does-it-work/>, accessed 6 November 2017. |

| 9 | George & Rheinberger, op. cit. |