This article refers to the original Japanese-language release.

Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai (2018) opens in anticipation. Sheet glass fogs over with breath, only to be quickly wiped away as Kun (Moka Kamishiraishi), a four-year-old boy, stares out the window of his parents’ house. He’s awaiting the return of his mum (Kumiko Asō) and dad (Gen Hoshino), but, really, he’s awaiting the future. It arrives shortly in the form of his initially unnamed infant sister, who is soon given the moniker ‘Mirai’: ‘future’ in Japanese.[1]In Japanese, Mirai’s full title is Mirai no Mirai, translating to ‘Mirai of the Future’. Over the coming months – and by way of fantastical adventures through space and time – Kun will grow to love his new sibling, as Hosoda builds on the themes of familial interdependence established in his earlier films.

But first: fierce jealousy. Like any only child relegated to the role of older, now-oft-ignored sibling, Kun reacts to his sister’s entry into his life in a way that is anything but decorous. As Mirai makes increasing demands on their parents’ attention while remaining seemingly unmoved by Kun’s beloved bullet-train toys, Kun’s envy manifests in violence – as when he bonks his sister on the head with one of said toys out of sheer frustration. This moment is at once shocking and familiar; growing up, I can recall watching more than a few Saturday-morning cartoons centring on this precise brand of envy.

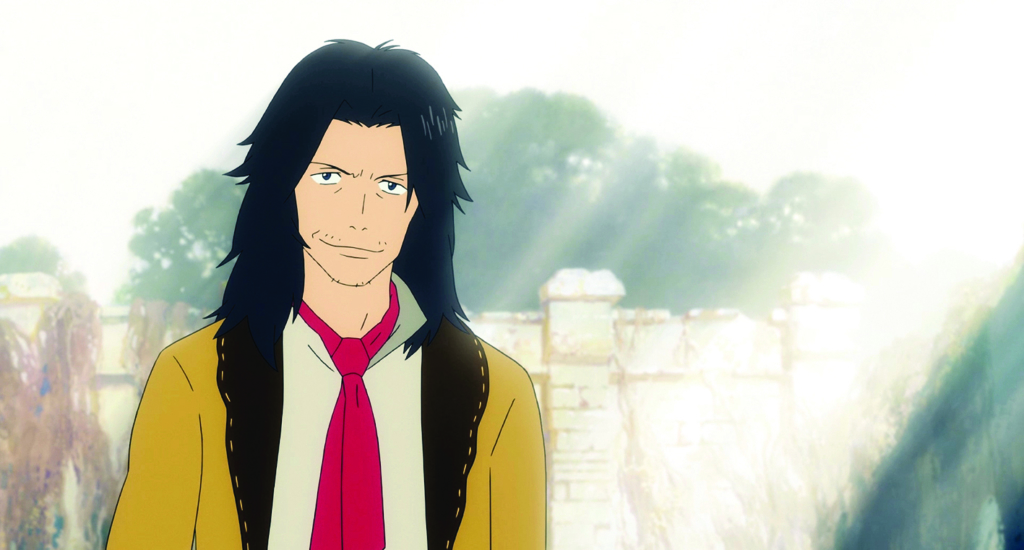

Hosoda is interested in more than just simple messages in a slice-of-life setting, however. Shortly after his sororal assault, Kun encounters a mysterious, floppy-haired fop in the courtyard dividing his family home, the domestic garden dissolving into ancient temple grounds. This princely figure (Mitsuo Yoshihara) explains that he, too, is a deposed ruler, diagnosing Kun thus: ‘I’ll tell you what you’re feeling: jealousy, plain and simple!’ The ‘prince’ would know, of course; not too long ago, Kun’s parents ‘caressed [his own] head and told [him he] was a good boy’.

Yes, this apparent dandy is, in fact, Yukko, the family dog, himself demoted after Kun’s birth four years prior. The film never quite explains if this sojourn into a world of anthropomorphised animals is a dream, reality or something in between. That befits the perspective of a young child, whereby the rules of reality haven’t quite been established; it’s also hardly a major concern to the audience, as the story swiftly launches into a sequence of similarly implausible encounters that evoke Hosoda’s previous work. Just as Yukko recalls the genial wolf–human hybrids of Hosoda’s Wolf Children (2012), the appearance of Mirai (Haru Kuroki) as a young adult reminds us of the time-travelling hijinks of the director’s defining feature, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (2006).

These two mystical visits in Mirai are succeeded by three more. Kun’s family courtyard opens up through raging waters onto a street, where he encounters his mother at his own age; then it’s a plane hangar, where he finds his great-grandfather (Kōji Yakusho) as a young man; and, finally, it’s a countryside train station bearing a monstrous incarnation of one of Kun’s beloved bullet trains. Like Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, each outing is a lesson of sorts for our young protagonist. Kun learns that his mother was once as messy and irresponsible as he is. He learns to be confident in attempting to ride a bike by doing the same with his great-grandfather’s motorcycle. He learns …well, honestly, I’m not entirely sure of what lesson is imparted by the terrifying train trip, which feels somewhat out of place alongside the other episodes.

Mirai boils down to a straightforward message: be a good brother. But, while there is a charming simplicity at the heart of this story, there’s more to Mirai than a feature-length version of those Saturday-morning cartoons I grew up on, as Hosoda is interrogating and developing the ideas of family presented in his previous two films, Wolf Children and The Boy and the Beast (2015).

Life lessons

Mirai’s house – designed by Kun’s architect father – is a unique structure. A front-facing family area, often scattered with Kun’s miniature trains, sits above an entry corridor, both of which lead to the central rectangular courtyard that is the locus of the film’s flights of fantasy. In the middle of the courtyard is a sprawling oak tree; later, future-Mirai describes it as the ‘index for [their] family’. On the other side of the courtyard, there’s a dining area and steps up to a kitchen; beneath the kitchen lies, presumably, the parents’ bedroom, the bathroom and the laundry. The net effect is that of openness; built to emphasise transparency and to reject traditional, demarcated rooms, the house acts as a compact and coherent metaphor for Hosoda’s view of family: challenging, occasionally impressive but reliant on interdependence and understanding to stay upright.

Describing the meaning of the film in an interview, Hosoda explains that Kun is ‘learning that it’s not [just] about receiving love, you also must give it. So, it’s a story about growing up’.[2]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Roxy Simons, ‘Mamoru Hosoda Interview’, MyM Buzz, 6 October 2018, <http://www.mymbuzz.com/2018/10/06/mamoru-hosoda-interview/>, accessed 16 October 2018. Over the film, Kun undertakes his first small steps on the path to grasping familial obligation. His excursions with his great-grandfather give him the confidence to assert his own independence: he learns to ride a bike at the park and makes friends with the local boys in the process. By uniting with future-Mirai to pack away a Hinamatsuri[3]Also known as Girls’ Day: a seasonal festival occurring in March, commemorated at home with an elaborate display of dolls. shrine – one that will, according to superstition, delay her marriage by a year for each day it remains on display – he learns to offer support to his sister rather than holding onto the childish expectation of perpetual support. But Kun is not the only character compelled to reframe their identity in Mirai. A few months after Mirai’s birth, Kun’s mother returns to work, leaving her husband in the unfamiliar position of primary housekeeper. As she cautions him, ‘You have to actually handle the housework, not just talk about it’ – a warning that proves prophetic in the case of the forgotten dolls’ shrine. The interdependence that Hosoda positions as key to family requires adaptation – and, perhaps, a bruising of one’s pride – but it also requires work.

The prominence of the shrine in the story is perhaps just an excuse for an extended set piece; the scene that sees Kun and future-Mirai – who can’t coexist with her infant self for reasons that remain happily unexplained[4]The characters in the film themselves seem puzzled by the ‘rules’; the human form of Yukko wonders, for instance, whether ‘Mirai from the future and baby Mirai can’t exist simultaneously’. – conspiring to ensure the shrine is packed away without their father noticing is joyously entertaining. Certainly, it’s easy to overanalyse the film. Mirai is first and foremost an opportunity for fantastical, family-friendly adventures. But the presence of the shrine hints at how Hosoda has subtly woven Japanese culture and history through his screenplay.

That’s primarily evidenced in Kun’s encounter with his great-grandfather. That interlude serves a specific purpose in the sense of imparting a message: through his ancestor, Kun develops self-assurance and bravery, which aid him in learning to ride his bike without training wheels. More broadly, it grants Kun some understanding of history, both within his family – he bears witness to the footrace that was a key part of his great-grandfather’s courtship of his great-grandmother, which acts as a kind of family legend trotted out at the dinner table – and even within his nation. Kun’s great-grandfather walks with a limp from injuries sustained in the war, and, in a brief shot, we see him stranded at sea surrounded by dead or injured soldiers. As much as Mirai is an intimate story of one family, these inclusions are concerted reminders that families exist as part of a much larger societal tapestry … even if this tapestry remains off screen for much of the film’s running time.

Wolves, beasts and boys

The narratives of Hosoda’s previous two films stretch over years: Wolf Children follows its child protagonists from birth to adolescence, while The Boy and the Beast similarly chronicles the path of its titular boy towards manhood. Mirai occurs over mere months, yet continues Hosoda’s mastery of fluid transitions – whether from day to day or when travelling decades into the past. As Anthony Carew noted in his profile of the director for this very magazine, Hosoda is ‘an artful, masterful proponent of one of movie-making’s most tired tropes: the passing-of-time montage’,[5]Anthony Carew, ‘The Fullness of Time: The Anime Films of Mamoru Hosoda’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, p. 43. and that talent is on full display here. Mirai is tightly connected to these predecessors beyond its formal qualities, however; across the three films, Hosoda offers an interrogation of familial relationships that’s at once coherent and conflicted.

Hosoda’s vision of growing up across these three films revolves around the evolution of identity. In Mirai, that process is decidedly small-scale, with Kun gaining life lessons relating to love and responsibility, whereas the broader time scales of Wolf Children and The Boy and the Beast allow for wider examinations of how identity shifts with respect to family bonds.

Hosoda has described Mirai as a ‘more realistic’ representation of parenthood than that in Wolf Children, describing the latter’s mother character, Hana (Aoi Miyazaki), modelled on his own mother, as ‘perfect’.[6]Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Andrew Osmond, ‘Interview: Mamoru Hosoda’, All the Anime, 25 September 2018, <https://blog.alltheanime.com/interview-mamoru-hosoda/>, accessed 16 October 2018. Indeed, while Hana faces some significant challenges raising her children – both the familiar struggles of making ends meet and less familiar difficulties like grappling with whether to send her half-wolf offspring to the veterinarian or the doctor – she’s a paragon of patience and understanding when it comes to accommodating her children’s disparate needs.

Hana’s daughter, Yuki (Momoka Ōno as a child / Haru Kuroki as a teenager), and son, Ame (Amon Kabe / Yukito Nishii), each represent different paths to maturity. Yuki is a rebellious, spirited infant who – after the pressures of school – matures into a polite young woman able to negotiate the intricacies of adult society. Ame, meanwhile, grows from a timorous child into a wild, independent teenager embracing his wolf heritage. Hana’s perfect parenting involves both challenging her children and, most importantly, supporting them. When Yuki finds that dead bugs don’t enthral her schoolgirl peers, Hana sews a nice dress for her. And the film concludes with Hana allowing Ame to leave the strictures of human society for the woods, after a dream in which his wolf-father tells her that Ame ‘knows where he’s supposed to be’. Both Mirai and Wolf Children propose that effective parenthood is about setting high expectations while also allowing your children to develop their own autonomy. When Kun’s dad tries – and, at first, fails – to teach him to ride his bike, for instance, they only achieve success when Kun brings his own motivation to bear.

Yet this (arguably idealised) presentation of parenting is distinct from the more fractious relationships at the core of The Boy and the Beast. The central relationship of this film is between orphan Ren (Miyazaki as a child / Shōta Sometani as a teenager) and the beast Kumatetsu (Yakusho, again). While the bond between the two is unmistakably paternal, you could hardly characterise it as supportive and warm, at least initially. Each begins the protégé–mentor relationship as a prickly, independent character: Ren – now named Kyūta – found his way into the Beast Kingdom after running from his legal guardians, while Kumatetsu’s work ethic is questionable at best.

It isn’t until the film’s third act that a connection to the themes of Mirai, particularly the importance of interdependence, becomes clear. A villain – Ichirōhiko (Haru Kuroki / Mamoru Miyano), the adopted son of Kumatetsu’s rival, in denial about his human heritage – rises. He’s driven by a void in his heart that consumes him; it’s a void that Kyūta shares. That void is filled (quite literally) by Kumatetsu’s spirit, suggesting, particularly in light of Hosoda’s films bracketing The Boy and the Beast, the importance of unity in overcoming obstacles. The void is an all-encompassing metaphor – for grief, depression, self-doubt – that gels neatly with how Kun’s self-confidence is buoyed by visitors from his family’s past, present and future.

Compared to his preceding films, Mirai may not offer any new additions to Hosoda’s ongoing portrait of healthy family living. It’s undeniably more accessible, with next to no conflict and a visual style that will – with the possible exception of the nightmarish bullet-train scene – appeal to young children and older anime aficionados alike. Together, these three films form a heartwarming trilogy about happy families: a rare, modest achievement in an era of spectacle-centric filmmaking.

Endnotes

| 1 | In Japanese, Mirai’s full title is Mirai no Mirai, translating to ‘Mirai of the Future’. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Roxy Simons, ‘Mamoru Hosoda Interview’, MyM Buzz, 6 October 2018, <http://www.mymbuzz.com/2018/10/06/mamoru-hosoda-interview/>, accessed 16 October 2018. |

| 3 | Also known as Girls’ Day: a seasonal festival occurring in March, commemorated at home with an elaborate display of dolls. |

| 4 | The characters in the film themselves seem puzzled by the ‘rules’; the human form of Yukko wonders, for instance, whether ‘Mirai from the future and baby Mirai can’t exist simultaneously’. |

| 5 | Anthony Carew, ‘The Fullness of Time: The Anime Films of Mamoru Hosoda’, Metro, no. 193, 2017, p. 43. |

| 6 | Mamoru Hosoda, quoted in Andrew Osmond, ‘Interview: Mamoru Hosoda’, All the Anime, 25 September 2018, <https://blog.alltheanime.com/interview-mamoru-hosoda/>, accessed 16 October 2018. |