Documentary offered itself as the form par excellence for affirmation film, partly because it is cheaper and easier to do tolerably than fiction, partly because of its historical association with progressive movements, and especially for its supposed special relationship to reality.

—Richard Dyer[1]Richard Dyer, Now You See It: Studies on Lesbian and Gay Film, 2nd edn, Routledge, London & New York, 2003, p. 223.

The police didn’t like seeing a lot of homosexuals together being happy, and they wanted to put us away for that and that seemed to be our crime. From being like an outsider in society, a deviant or what society sort of chooses to call us, we didn’t have any legal protection then. We were outside of the law.

—unnamed lesbian 78er[2]Appearing in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters.

‘Fearless’ was the theme for the 2019 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. This upbeat festival branding nods to the courage required to live an authentic identity, particularly one that jars with the heteronormative mainstream. The cultural bubble of cosmopolitan, urbane Sydney seems a fitting place for this extravagant celebration of LGBTQIA+ experience; after all, there is insulation to be found in an international city, a kind of social buffer that fends off prejudice, stigma and judgement. Sydney’s Oxford and Flinders streets are pedestrianised for one night to make way for the Mardi Gras centrepiece event; this year, the annual parade drew around 500,000 spectators who spilled out onto balconies and rooftops, and jostled for position at street level. More than 12,500 marchers from diverse groups took part.[3]‘Mardi Gras Parade Marches Fearlessly into the Future’, media release, Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, 3 March 2019, <http://www.mardigras.org.au/news/mardi-gras-parade-marches-fearlessly-into-the-future>, accessed 30 May 2019. After the First Nations representatives, Dykes on Bikes, Rainbow Families and Trans Pride floats, the NSW Police Force rolled in. A female officer belted out a Whitney Houston number from the float, while a cohort of officers marched in front of the vehicle. Their appearance was greeted by appreciative whoops from the crowd.

Amid all of the high-octane beats, the costumes and the general air of revelry, it was easy to miss the comparatively low-key appearance of the original Mardi Gras participants – or ‘the 78ers’, as they are now widely known. They are well past middle age now, and their truck arrived sans the glittery festive accoutrements that have become synonymous with the modern Mardi Gras (or ‘gay Christmas’,[4]Cited in ‘Kylie Minogue’s Surprise Appearance at “Fearless” Mardi Gras Parade in Sydney’, News.com.au, 3 March 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/national/nsw-act/news/fearless-mardi-gras-parade-kicking-off-in-sydney/news-story/dadf584d7cfaa8a80726366efb02d6e0>, accessed 30 May 2019. as one attendee called it). While the shift in tone was subtle – the music still played, and the pride flags were still held aloft – here was a kind of distillation of the intent that underpinned that first gathering forty-one years ago: that of individuals standing together in simple solidarity. Back then, they embodied a collective oppositional force, a rebuke to a society that sentenced them to life at its very fringes.

In 1978, the NSW Police Force, now so neatly integrated into the modern parade, were the harbingers of that hatred of the Other that blindly oppresses. Their brutal interventions helped focus the cultural dialogue; questions were asked about the role of the police as arbiters of the people’s will. As journalist and commentator David Marr has pointed out, ‘When the police overstep the mark, they make reform inescapable.’[5]David Marr, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, ABC News, 4 March 2016, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-03-04/nsw-police-apologise-to-mardi-gras-78ers/7219996>, accessed 30 May 2019. In a recent ABC News article, protester Sandi Banks recalls her treatment by the police on the fateful night of 24 June that year, soon to become the precursor to Mardi Gras:

They came racing down Darlinghurst Road, sirens going, lights galore and they jumped out, lots of them. Very huge men at the time and no form of identification. And they started grabbing, thumping, bashing, pulling hair. They picked me up and threw me towards the paddy wagon … my chest was black and blue from having hit the truck.[6]Sandi Banks, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, ibid.

It’s clear that the 78ers are powerfully emblematic of the strides Australia has made socially, politically, culturally and judicially; their courage truly embodies the notion of ‘fearless’. In 1978, their street-festival-turned-protest initiated a turning point in the landscape of LGBTQIA+ rights in Australia. It’s almost impossible to overstate the significance of their legacy.

Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters (Digby Duncan & One in Seven Collective, 1980) charts the fallout from the police attacks and the ensuing discrimination that the protesters endured; fifty-three people were arrested and many were beaten. The film tracks the subsequent marches and protests over the following two months that saw a staggering total of 178 arrests.[7]While the film cites the number of arrests as 184, modern-day sources put the figure at 178; see, for example, Shannon Verhagen, ‘A History of Sydney’s Mardi Gras’, Australian Geographic, 17 June 2016, <https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/blogs/on-this-day/2016/06/on-this-day-sydneys-first-mardi-gras/>, accessed 30 May 2019. We see the Drop the Charges committee campaigning with pamphlets that itemise the places, dates and numbers of the arrests. It is this kind of firsthand historical documentation, which the film intercuts with footage of the protests and first-person accounts, that makes Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters such an important living archive. The film was partially funded by a grant from the Australian Film Commission, with additional financial support from The Gay Film Fund, a grassroots Sydney organisation that was set up to fund gay and lesbian projects in the local community.[8]Scott McKinnon, ‘Witches, Faggots, Dykes and Poofters’, in James E Bennett & Rebecca Beirne (eds), Making Film and Television Histories: Australia and New Zealand, I.B.Tauris and Co., London & New York, 2011, p. 225. This essay preserves McKinnon’s formatting of the film’s title.

The events captured in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters became a catalyst for significant queer activism; they provided a springboard for the initiation of gradual sociopolitical change, from broader public awareness of the mistreatment of gay and lesbian Australians to changes in law that reflected a movement towards a more accepting, more inclusive culture. There was a dramatic increase in public exposure for the gay and lesbian activists who demanded respect and equality, and their high-profile protests resulted in the Parliament of NSW repealing its Summary Offences Act 1970, which had permitted the arrests to be carried out in the first place, in 1979.[9]See Garry Wotherspoon, ‘Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, <https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/gay_and_lesbian_mardi_gras>, accessed 30 May 2019. In this way, the film chronicles a hugely important civil-rights landmark in Australian history – one that has created a legal precedent and thus, like all political milestones shaped by collective activism, ultimately transcended the specific politics and concerns of the immediate community affected.

Comprising interviews as well as archival and recorded footage, the documentary channels the anarchic spirit of political protest. The provocative title evidences a reappropriation of homophobic language. Right at the beginning of the film, one of the lesbian activists explains the rationale at play:

It was really crucial to […] use the word ‘dykes’ and use the word ‘poofters’, because we had to take these terms of abuse and sort of say, ‘Alright, I’m proud of being a “dyke”.’ And a lot of the men took the term ‘poofter’ and said, ‘I’m proud of being a “poofter”.’ And so for a long time, in Melbourne in particular, it was always the ‘dykes’ and ‘poofters’.

By interposing the terms ‘faggots’, ‘dykes’ and ‘poofters’ with the historical reference ‘witches’, Duncan and her co-directors marshals the idea of persecution as an ever-present – however perverse – component of Australia’s cultural tapestry. By invoking witches, the film immediately locates itself within a robustly political framework: film as protest, film as mirror, film as sociological artefact. In foregrounding the intersections between gender inequality and homophobia, Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters points up the absurdity of both iterations of persecution. The title also functions as an ironic allusion to the kind of dangerous terrain that can swallow up logic in the service of patriarchal control. It hints at the hysterical fearmongering that comes from prejudice and the desire to keep minority voices silent. For Digby herself, the title remains hugely important to this day:

I am always struggling to preserve the name of the film – ‘Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters’. There is a tendency to shorten the film to ‘Witches’, which bundles it into all the other films named ‘Witches’. I feel this also avoids writing or saying the title […] I feel it is important to refer to it [in full] for its historical reference and its boldness.[10]Digby Duncan, email interview with author, 2 May 2019.

To mark the fortieth anniversary of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) restored this seminal documentary. The transformation of the event from that first gathering of 1000 people[11]Wotherspoon, op. cit. to an international tourist attraction and highlight of the LGBTQIA+ calendar is analogous with the changing sociocultural climate around gender and sexuality issues in Australia. The film is an enlightening catalogue of queer activism that captures the grassroots mobilisation of some of Australia’s first gay and lesbian political groups, the spirit of protest in the name of tolerance and the self-determination that animated them, as well as the deep-rooted contempt for the queer community that the 78ers and their allies had to negotiate. While the interviews in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters are both intimate and uncensored, the subjects themselves are never named – symptomatic of the status of LGBTQIA+ Australians at the time. This is unsurprising, given the troubling fact that The Sydney Morning Herald published the names, addresses and occupations of those arrested; as a result, some lost homes and jobs, and fell out with family members.[12]See Michelle Brown, ‘Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras 78er Ron Austin Dies Aged 90’, ABC News, 14 April 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-14/mardi-gras-founder-ron-austin-dies-aged-90/11001404>, accessed 30 May 2019. Without any legal protection for gays and lesbians, the risk of being ‘outed’ was a tremendous source of anxiety for many. Those unable to emerge from the ‘closet’ were worried about losing friendships, jobs and familial relationships if their sexuality was exposed.

Against this emerging backdrop of a slowly legitimising non-heterosexual identity, the kind of symbolic transgression of public space enacted by the police proved even more incendiary … This notion of reclaiming queer space is central to the events depicted.

Duncan’s co-directors were the One in Seven Collective, a group of lesbian feminists. The ‘one in seven’ in the collective’s name signalled its aim to educate audiences about homosexuality: it invoked research claiming that one in ten people would have some kind of homosexual experience in their lifetimes, but the group felt that the rate of incidence would be closer to one in seven.[13]Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit. Indeed, the resulting documentary foregrounds the voices, experiences and often politicised arguments of a community that was, at the time, highly misrepresented. It records the first-person responses of gay and lesbian subjects in the midst of a turning point in the epoch of queer history in Australia.

The police and institutional prejudice

In 1978, Sydney was far from today’s sanctuary of anonymity and freedom for its gay and lesbian inhabitants. Talking about the evening of the arrests, Marr recalls that the city ‘could not believe the hate that was in the air that night.’[14]Marr, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, op. cit. In many ways, the police brutality inflicted on the 78ers was a disturbing barometer of the widespread homophobia and climate of persecution that pervaded Australian society at the time.

In the decades preceding the first Mardi Gras, the police were front and centre in a series of incidents across the country that emphasised the extent of this persecution – a pattern of abuse that saw gay men in particular singled out for systemic mistreatment. Even in the supposedly more socially progressive cities of Melbourne and Sydney, the police deployed alarming tactics that actively undermined the rights of gay men within both public and private spaces. Under the rather vague ‘soliciting for immoral purposes’ clause, police were able to target gay men in their own environments. An ACON review of gay and transgender prejudice killings in NSW points out the historical role of police as the guardians of homophobic sentiment:

And the police, as enforcers of the law and reflecting prevailing social attitudes, had little toleration for what they saw as perverts, degenerates, effeminates, and paedophiles […] And it would seem that they were given unofficial blessing for this when the Roman Catholic Superintendent of Police in Sydney and later Police Commissioner, Colin Delaney, declared in the late 1950s that homosexuality was ‘the greatest social menace facing Australia.’[15]Cited in ACON, In Pursuit of Truth & Justice: Documenting Gay and Transgender Prejudice Killings in NSW in the Late 20th Century, Surry Hills, 2018, p. 31, available at <https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf>, accessed 30 May 2019.

Homosexuality was illegal in NSW until 1984, and the police routinely employed deceptive techniques to entrap gay men and then arrest them at established ‘beats’ (gay meeting places). Unsurprisingly, the review found that, in NSW, ‘homophobia shaped the development and enforcement of laws that had violent and lasting impacts on the community’.[16]ibid., p. 20.

Victorian police were just as discriminatory, even resorting to the expulsion of a gay couple after police ‘discovered’ they were cohabiting: in 1975, The Age reported that Lindsay and John were arrested and charged with ‘the ancient crime of buggery’. The couple were forced to leave their jobs, family and friends, and relocate to South Australia, where homosexuality was legal.[17]Phillip Adams, ‘Boys in Blue’, The Age, 9 April 1975, p. 8. During the summer of 1976–1977, Victorian police then carried out undercover operations at a number of established beats, with an emphasis on Melbourne’s Black Rock Beach. In a bid to enforce the law against homosexuality, young officers were schooled in ‘gay mannerisms’, and then sent in to entrap and arrest men for loitering, soliciting for sex or even sunbathing naked. More than 100 men were arrested at Black Rock Beach.[18]Graham Carbery, Towards Homosexual Equality in Australian Criminal Law – a Brief History’, rev. edn, Australian Lesbian & Gay Archives, Melbourne, 2014, p. 11, available at <http://www.alga.org.au/files/towardsequality2ed.pdf>, accessed April 1 2019.

The provocative level of deception used by police at Black Rock did, however, become a talking point in the media, sparking widespread public debate.[19]ibid., p. 12. Similarly, the tone of the earlier Age piece is contemptuous of the role of the police, suggesting the emergence of more liberal attitudes to gay and lesbian rights while underscoring the police’s reluctance to adopt more progressive policies:

As a result of the magistrate’s extraordinary sentence, they’ll have to leave their jobs and friends. All because someone in the Victoria Police – those men of upright morals and truncheons – disapproved of what was going on behind their venetian blinds.[20]Adams, op. cit., p. 8.

Territorialising space: Queering the streets and the screen

During the late 1970s, the suburbs around Sydney’s Oxford Street became established gay precincts, with bars, clubs and other businesses explicitly targeting gay and lesbian consumers. This area became known as the ‘golden mile’. In tandem with this social stratification, the ‘pink press’ emerged: publications like Campaign, OutRage and Star Observer all contributed to the sense of a ‘gay identity’ and the development of a queer community within a geographically localised urban space.[21]ACON, op. cit., p. 11. At the same time, gay and lesbian activism had become an increasingly public presence, with demonstrations on the rise. The more ‘liberal’ sectors of society were starting to take notice of the inequality and speak up in support of law reform. Queer grassroots organisations like the amusingly named CAMP (Campaign Against Moral Persecution) in Sydney, the Homosexual Law Reform Society in Canberra and Society Five in Melbourne were all working to influence politicians and lawmakers, and to increase the visibility of the gay and lesbian community.[22]See ‘Ben Winsor, ‘A Definitive Timeline of LGBT+ Rights in Australia’, SBS Sexuality, 12 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/08/12/definitive-timeline-lgbt-rights-australia>, accessed 30 May 2019.

Against this emerging backdrop of a slowly legitimising non-heterosexual identity, the kind of symbolic transgression of public space enacted by the police proved even more incendiary; the police operations clearly set out to infiltrate and repossess ‘queer’ locations. This notion of reclaiming queer space is central to the events depicted in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters. The aggressive police tactics and protester arrests (many of which were later condemned as arbitrary and effectively ‘illegal’) highlight the politicisation of public space: the streets of Sydney were sites of visibility for the gay and lesbian community and, as such, were sites transforming from a ‘regulated’ (heteronormative, patriarchal) public space to a perceived ‘unregulated’ (homosexual, dangerous) one.

Towards the end of the film, we see activists holding a poster that reads, ‘We are the people our parents warned us against.’ This provocative engagement with an outsider status speaks to the politics of marginalisation: those denied a presence in mainstream public life claiming an identity. The notion of space also aligns with the politics of queer activism and the act of mobilising the camera effectively to ‘claim’ the sociopolitical territory that is being denied to its subjects. Writing about the film, historian Scott McKinnon refers to the ‘weaponising’ of the camera as a means of self-regulation and control of the ‘messages which were presented about them’:

the camera could be a weapon of oppression which threatened to expose those who wished to remain hidden. Witches, Faggots, Dykes and Poofters reflects a significant shift whereby the camera was recruited as a weapon of liberation, which enabled gay and lesbian people to tell their own truth and claim the right to live openly. It is a call to ‘come out’ as a means to achieve equal rights and indicates a defiant choice to be seen and to be heard.[23]McKinnon, op. cit., pp. 225, 227.

Clearly, the personal is political; from Duncan’s production team of volunteers to the subjects being filmed, authentic representation is at the heart of the film. Visibility and ‘coming out’ are keynotes of the conversations presented in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters. As one protester in the film says: ‘We’re forced into invisibility in order to allow other people to feel comfortable.’

From reclaiming the public spaces of the city’s streets to having their sexuality acknowledged as different but not ‘deviant’, this is a work that speaks to an emerging queer cinematic culture in Australia. It’s significant that the world’s first ever gay film festival, the Festival of Gay Films, took place in Sydney – at the Filmmakers Cinema in June 1976.[24]Ricardo Peach, ‘Queer Cinema as a Fifth Cinema in South Africa and Australia’, PhD thesis, University of Technology Sydney, 2005, pp. 212–3. And, indeed, Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters was first screened to an audience of mostly gay and lesbian people at this venue in June 1980. The audience was too large for the eighty-seat cinema, so two screenings were held; people still had to be turned away. A party for the queer community was then held after the screening.[25]Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit.

According to Duncan, the main production difficulties that she and the team encountered were financial: ‘The initial money came from the community as we passed around the hat at each event we filmed. People also donated their time, film and equipment.’ A work of activism, the film was a labour of love for the filmmakers; they had to sporadically cease work on it in order to return to paid employment as their personal funds were gradually depleted. This made the production process more lengthy than it might have been had they secured sufficient financing. The film cost approximately A$32,000 to make, including concessions to unpaid labour. A New Zealand editor, Melanie Read, offered her services free of charge; she spent five months editing the film but had to return home to a paying job.[26]ibid.

As researcher Samantha Searle has rightly pointed out, in order to adequately assess queer cinema culture, it cannot be extracted from its political framework. She particularly emphasises the importance of representation, along with queer filmmakers having access to a means of production as well as a means of distribution in order to effectively control both the creative and the screening spaces.[27]Samantha Searle, Queer-ing the Screen: Sexuality and Australian Film and Television, The Moving Image series, no. 5, ATOM, St Kilda, Vic., 1997, p. 7. Within this framework, Duncan’s film takes on even greater significance; beyond the milestones for gay and lesbian rights that she has recorded, the symbiotic interactions between production, representation and audience mark an additional milestone in Australian queer film history. Here is a documentary that is partially funded by the community, and that sets out to counter the negative stereotyping of gay and lesbian Australians that dominated the media, particularly film and television, back in 1980.

In many ways, Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters can be viewed as a turning point in the representation of Australian gays and lesbians. Perhaps most importantly, it enabled queer audiences to see themselves reflected back in an authentic, dynamic way, potentially for the first time ever. Pioneering critic of the ‘New Queer Cinema’ of the 1990s B Ruby Rich argues that queer audiences take on a sense of propriety and collusion when it comes to representation:

Queer viewer responses are inflected by something far more specific and complex than the subjective tastes governing mainstream movie choices. Queer audiences see themselves as complicit in these representations, as if they were compromised or validated by them, and the cathexis they experience surpasses other audiences’ investments.[28]B Ruby Rich, ‘Collision, Catastrophe, Celebration: The Relationship Between Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals and Their Publics’, GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 1999, pp. 83–4.

Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters is not a ‘naturalistic’ record of reality: in fact, it uses the documentary form to reorient the representation of gays and lesbians … the goals of activism, affirmative representation and gay liberation are aligned.

Given this sense of queer ‘ownership’ over the image, the community represented in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters would have found tremendous transformative power in it. For while the sociopolitical landscape was gradually shifting, the film was a call to arms for gays, lesbians and their allies. The act of recording the marches, arrests and meetings is also an act of defiant refusal – a refusal to be ignored, a refusal to be stereotyped – but, most of all, it is a material commitment to the preservation of visibility. In this way, Duncan’s documentation of events was an inherently radical activist gesture: a means of countering the oppressive paradigms of invisibility and of negative representation that associated non-heterosexuality with illness, perversion, or a more general failure or ‘lack’.

Images of redress

Lesbian visibility was particularly low in Australia in the late 1970s; in keeping with the issues of representation and control associated with a patriarchal framework, it was men who were generally in charge of the formulation and perpetuation of messages about who mattered. As a result, gay men were featured far more prominently in the public consciousness, and it was gay men who controlled the narrative of discrimination. They tended to focus on their own experiences, relegating those of women at best to the background, and at worst into complete irrelevance. This was even reflected in Australian law; as activist and historian Graham Carbery puts it:

While all Australian [s]tates outlawed sexual behaviour between males, the law was silent on the question of lesbian behaviour. It is difficult to know why this was the case but it probably had a lot to do with the commonly held 19th century belief that unlike men, women did not have strong sexual desires, therefore the possibility of women being sexually attracted to other women did not occur to (male) politicians.[29]Carbery, op. cit., p. 3.

Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters redresses this gender imbalance. We meet a lesbian single mother who is battling the courts to maintain custody of her daughter; a lesbian teacher who is worried that she will be fired; a lesbian feminist who acknowledges the political necessity of ‘outing’ herself, but is anxious about losing her female best friend in the process. Most distressingly, there is the lesbian who endured a ‘leucotomy’ (an alternative term for lobotomy) to ‘correct’ her sexuality. In an affectless tone, she explains that she can no longer work because her concentration has been so impaired: ‘My creativity has been destroyed. I used to paint a bit and write poetry. I can’t do that anymore. Which has made things pretty meaningless.’ Severely depressed as she was at the time of surgery, a team of male doctors decided on her behalf that she should have the procedure. Alongside the vigorous tide of activism that Duncan charts, these first-person stories humanise a population that was deprived of a voice for far too long.

Such genuine diversity of representation chimes with the film’s broad sociohistorical reach. There is a wider objective underpinning Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters: a commitment to educating its audience (whether LGBTQIA+ or heterosexual) about the oppression of queer people throughout history and across cultures. As Duncan explains:

The film, even with only a brief documentation of this history, reveals the reality of the oppression of homosexual people and how relentlessly in the name of gods, kings and ‘our way of life’, this oppression has been perpetrated.[30]Digby Duncan, interview with Tina Kaufman, Filmnews, vol. 10, no. 6, June 1980.

The opening sequence is a montage that locates the local conversation about gay rights within a historical framework of hysteria, prejudice and abuse dating back to the Middle Ages. The voiceover is delivered by Jude Kuring, best known for her role as Noeline Burke in the TV series Prisoner (which, coincidentally, has gone on to become a cult lesbian series[31]Rebecca Beirne, ‘Screening the Dykes of Oz: Lesbian Representation on Australian Television’, in Sara E Cooper (ed.), Lesbian Images in International Popular Culture, Routledge, London, 2010.). Medieval music sets a sombre tone that emphasises the sadly enduring correlation between ‘then’ and the year that the film was recorded. Still images accompany a voiceover describing the crime of ‘heresy’, which saw women, including lesbians, labelled ‘witches’ and burned at the stake. Kuring explains that the bodies of gay men were used as wood for fires (which were referred to as ‘faggots’). She claims that some homosexual men in Nazi concentration camps were asked to ‘prove’ their heterosexuality by raping women. The film proceeds to reference Stalinist Russia, the 1950s ‘witch-hunts’ of US senator Joseph McCarthy, through to the Stonewall riots that provoked the International Day of Gay Solidarity, which Australia’s ‘dykes and poofters’ chose to commemorate on 24 June 1978 – the day of the first Mardi Gras. Threaded throughout the sequence are early examples of queer protest and the fledgling assembly of activist groups.

While the events depicted in the montage are filtered through a Western (predominantly European/US) lens, it is an effective tool for establishing a context beyond the isolated geography of Australia. At the same time, it signals the documentary’s intention to present a dialogue about film-as-activism; the mode of address moves between provocative and derisive, and there is no taking up of an objective position, nor any attempt to flesh out nuance within the events referenced. However, this is very much in keeping with the style and aesthetics of the film. Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters is not a ‘naturalistic’ record of reality: in fact, it uses the documentary form to reorient the representation of gays and lesbians. The film’s privileging of authenticity helps it develop an emerging representational language that furthers the political agendas of radical lesbian feminism and gay human rights. The direct-to-camera address of the ‘talking head’ is used when recording many of the activists sharing their experiences; this shapes the illusion of ‘reality’ while intensifying the film’s political overtones. In this way, the goals of activism, affirmative representation and gay liberation are aligned.

The talking heads are intercut with a roving (often frenetic) handheld camera that presents an ‘on-the-ground’ activist’s point of view of the Mardi Gras street party as well as the subsequent arrests. One of the arrested women describes her inhumane treatment at Darlinghurst prison, where they were held in a small cell for six hours:

When we arrived at Darlinghurst […] I was shoved into a small room with twenty-four other women. And this cell was really designed for two people, and we had twenty-four of us. The space wasn’t sufficient for us all to lie down together. There was one toilet in the middle of this cell that the twenty-four of us had to use, and we couldn’t even get a drink of water, which we asked for repeatedly. And then we were just left for hours, and, like, nobody told us we could make a phone call or anything like that. And when we asked for our rights, we were told, ‘What rights?’

This is just one incident in a damning catalogue of police actions that ignored the protesters’ rights. A perfectly legal evening event that had been approved by the police turned into a violent and bloody stand-off. The recollections of abuse captured in the film also highlight the community’s contempt for the police; instead of protecting the streets from violence, the latter set out to take the streets back from the queer revellers. One young man recalls his experience, his anger palpable:

They just arrested people and threw them in the paddy wagons. I saw people being dragged by their hair, punched in the face, dragged by their legs, dragged across the road. Just every single right that a person’s entitled to in Australia has been blatantly denied by the police. And this station has just lived up to its reputation, as far as I’m concerned.

The police continued to breach established protocol, even going so far as to close the courthouse during the hearings of those arrested. This meant that friends, family and allies were not able to support the arrested protesters.

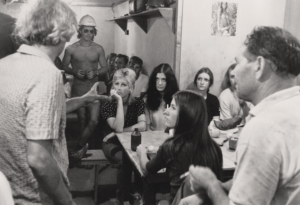

Some of the most powerful footage in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters is captured during heated exchanges at a meeting that was held to decide the activists’ next moves. Passionate, rage-filled and indignant, these meetings show us the rallying of an oppositional voice. This is Duncan’s favourite scene in the film:[32]Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit. shooting the meeting was sensitive, as many activists didn’t want themselves appearing. They feared that exposure would lead to discrimination, so the filmmakers agreed to keep one side of the room out of the shot, to capture only those who were willing. In this way, the production conditions intersected with the sociopolitical climate beyond the frame: the decision to speak up and contribute to the dialogue was not one taken lightly.

When one activist takes centre stage and voices her view, the room erupts with approval:

If you believe that we ought to ask police permission, why the fuck go and demonstrate about people who were arrested for illegal marching? What’s the point of it? If we’re going to crawl to the coppers and say, ‘Please give us our rights, baby,’ and we’re gonna stick by what the coppers allow us, then why the fuck demonstrate? People who were picked up for illegal marching were legitimately arrested. If you believe that crap, if you think the police should have the right to pick you off the streets because you haven’t obeyed their rules, then piss off!

And when the decision to march in solidarity with their arrested allies goes ahead, there is stirring footage of 3000 people walking with banners bearing messages like ‘Drop the Charges!’ The song that accompanies the images features a female voice singing the lyrics, ‘I’m gonna keep on singing and marching till you let me be. I don’t want to start no hassle but I gotta be gay and free.’

Learning our history, learning our selves

The scenes contained within Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters are a vital record of Australian queer history, as well as the history of activism and grassroots self-organisation in support of social change. While there has been an astonishing amount of relatively rapid change in Australia, with LGBTQIA+ residents now living in a far more inclusive climate of acceptance, there is still a long way to travel if equality is to be truly attained. Despite milestones like same-sex marriage being legalised as well as growing awareness of and support for transgender people, there is still a need for activism that builds on the pioneering work of the 78ers and their allies. The Australian education sector, with particular reference to primary and secondary schools, was recognised by the filmmakers as an essential space for change. In fact, Duncan concedes that the team’s ‘most ambitious hope was that [the film] would be shown in schools. That has not happened to date but it has reached universities and other tertiary institutions.’[33]ibid.

The issue of LGBTQIA+ teachers in religious schools risking dismissal for disclosing their sexuality remains an ongoing concern;[34]See, for example, Livia Albeck-Ripka, ‘In Some Australian Schools, Teachers Can Be Fired for Being Gay’, The New York Times, 18 October 2018, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/18/world/australia/gay-schools-teachers-religion.html>, accessed 30 May 2019. this mirrors the experience of the independent-school teacher featured in the film. The resonant theme of discrimination is concerning in a society that outwardly claims to be socially progressive. The fact that the film has not reached secondary schools today chimes with the highly politicised debates around sex and sexuality education in Australian schools. Programs like Safe Schools, for example, were taken up by extreme-right groups and used in anti-same-sex-marriage scare tactics.[35]See Emma Reynolds, ‘Myths Around Safe Schools and Same-sex Marriages Debunked’, News.com.au, 20 September 2017, <https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/gay-marriage/myths-around-safe-schools-debunked/news-story/374b23a137c5c9ac7b63ace15b9806c7>, accessed 30 May 2019. Clearly, for many conservative and religious stakeholders, teaching students about non-heteronormative forms of sexuality should remain off the agenda – and this risks LGBTQIA+ students feeling isolated, rejected or even aberrant. The issues also manifest in more oblique ways. A recent research paper by Kelli McGraw and Lisa van Leent from the Queensland University of Technology found that senior English texts are overwhelmingly heteronormative. The researchers contend that senior English staff should work to redress this by ‘listing texts that represent diverse sexual identities and issues of sexual difference and diversity, and texts that are equitably accessible to a wider range of students in English’.[36]Kelli McGraw & Lisa van Leent, ‘Textual Constraints: Queering the Senior English Text List in the Australian Curriculum’, English in Australia, vol. 53, no. 2, 2018, p. 28, available at <https://www.aate.org.au/documents/item/1654>, accessed 30 May 2019.

And these exclusionary approaches are not confined to classrooms. In NSW alone, at least thirteen defendants used the ‘gay panic’ defence to argue successfully for a lesser charge of manslaughter between 1993 and 1995. The legal argument hinges on the claim that a victim can ‘provoke’ his attacker through unwanted homosexual advances – provocation being defined as ‘a sudden and temporary loss of control at the point when the homicide [takes] place’.[37]Ben Winsor, ‘A Sordid History of the Gay Panic Defence in Australia’, SBS Sexuality, 12 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/08/12/sordid-history-gay-panic-defence-australia>, accessed 30 May 2019. The defence has since been banned in NSW and other states, and its last remaining stronghold in the country – South Australia – is set to dissolve its legal status by the end of the year.[38]Laurence Barber, ‘South Australia to Finally Scrap “Gay Panic” Defence by the End of the Year’, Star Observer, 9 April 2019, <http://www.starobserver.com.au/news/national-news/south-australia/south-australia-to-finally-scrap-gay-panic-defence-by-the-end-of-the-year/180675>, accessed 30 May 2019.

In 2016, the NSW Police Force formally apologised to the LGBTQIA+ community for their treatment in 1978. Superintendent Tony Crandell stated that the police were

[s]orry for the way that the Mardi Gras was policed on the first occasion in 1978. For that, we apologise, and we acknowledge the pain and hurt that police actions caused at that event in 1978. Our relationships today, I would say, are positive and progressive. That was certainly not the case in 1978.[39]Tony Crandell, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, op. cit.

With these conciliatory overtures, it might be tempting to assume that the 78ers’ courageous activism and the work of grassroots filmmakers like Duncan and the One in Seven Collective have come full circle. That the agents of social order are now appropriately aligned with the LGBTQIA+ community. That the events depicted in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters can be happily consigned to queer history. Yet the film ends abruptly, without warning; it is almost as if its brief forty-five minutes have been cut short prematurely. While this is most likely due to financial constraints, it creates the suggestion that the activist’s voice has exceeded its permitted running time. This is an alarming notion that reminds the audience – queer and straight – of the need to keep speaking up, to keep defending, to keep including and to keep listening. For while the legacy of the 78ers continues today in terms of rights gained and increased inclusion for LGBTQIA+ Australians, the activism that they delivered is a foundation that must continue to be built on.

This article has been refereed.

Select bibliography

ACON, In Pursuit of Truth & Justice: Documenting Gay and Transgender Prejudice Killings in NSW in the Late 20th Century, Surry Hills, 2018, available at <https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf>.

Graham Carbery, Towards Homosexual Equality in Australian Criminal Law – a Brief History’, rev. edn, Australian Lesbian & Gay Archives, Melbourne, 2014, available at <http://www.alga.org.au/files/towardsequality2ed.pdf>.

Richard Dyer, Now You See It: Studies on Lesbian and Gay Film, 2nd edn, Routledge, London & New York, 2003.

Tina Kaufman, interview with Digby Duncan, Filmnews, vol. 10, no. 6, June 1980.

Scott McKinnon, ‘Witches, Faggots, Dykes and Poofters’, in James E Bennett & Rebecca Beirne (eds), Making Film and Television Histories: Australia and New Zealand, I.B.Tauris and Co., London & New York, 2011.

Ricardo Peach, ‘Queer Cinema as a Fifth Cinema in South Africa and Australia’, PhD thesis, University of Technology Sydney, 2005.

Samantha Searle, Queer-ing the Screen: Sexuality and Australian Film and Television, The Moving Image series, no. 5, ATOM, St Kilda, Vic., 1997.

PRINCIPAL CREDITS

Year of release 1980 Length 45 mins Producer Digby Duncan Directors Digby Duncan & One in Seven Collective Funding support Australian Film Commission & The Gay Film Fund Camera Wendy Freecloud, Jan Kenny, Jeni Thornley, David Perry Sound Megan McMurchy, Wendy Freecloud, Jennifer Neil Editor Melanie Read Narrator Jude Kuring Music Pen Short & Hens Teeth

Endnotes

| 1 | Richard Dyer, Now You See It: Studies on Lesbian and Gay Film, 2nd edn, Routledge, London & New York, 2003, p. 223. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Appearing in Witches and Faggots, Dykes and Poofters. |

| 3 | ‘Mardi Gras Parade Marches Fearlessly into the Future’, media release, Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, 3 March 2019, <http://www.mardigras.org.au/news/mardi-gras-parade-marches-fearlessly-into-the-future>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 4 | Cited in ‘Kylie Minogue’s Surprise Appearance at “Fearless” Mardi Gras Parade in Sydney’, News.com.au, 3 March 2019, <https://www.news.com.au/national/nsw-act/news/fearless-mardi-gras-parade-kicking-off-in-sydney/news-story/dadf584d7cfaa8a80726366efb02d6e0>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 5 | David Marr, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, ABC News, 4 March 2016, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-03-04/nsw-police-apologise-to-mardi-gras-78ers/7219996>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 6 | Sandi Banks, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, ibid. |

| 7 | While the film cites the number of arrests as 184, modern-day sources put the figure at 178; see, for example, Shannon Verhagen, ‘A History of Sydney’s Mardi Gras’, Australian Geographic, 17 June 2016, <https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/blogs/on-this-day/2016/06/on-this-day-sydneys-first-mardi-gras/>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 8 | Scott McKinnon, ‘Witches, Faggots, Dykes and Poofters’, in James E Bennett & Rebecca Beirne (eds), Making Film and Television Histories: Australia and New Zealand, I.B.Tauris and Co., London & New York, 2011, p. 225. This essay preserves McKinnon’s formatting of the film’s title. |

| 9 | See Garry Wotherspoon, ‘Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, <https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/gay_and_lesbian_mardi_gras>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 10 | Digby Duncan, email interview with author, 2 May 2019. |

| 11 | Wotherspoon, op. cit. |

| 12 | See Michelle Brown, ‘Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras 78er Ron Austin Dies Aged 90’, ABC News, 14 April 2019, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-14/mardi-gras-founder-ron-austin-dies-aged-90/11001404>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 13 | Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit. |

| 14 | Marr, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, op. cit. |

| 15 | Cited in ACON, In Pursuit of Truth & Justice: Documenting Gay and Transgender Prejudice Killings in NSW in the Late 20th Century, Surry Hills, 2018, p. 31, available at <https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 16 | ibid., p. 20. |

| 17 | Phillip Adams, ‘Boys in Blue’, The Age, 9 April 1975, p. 8. |

| 18 | Graham Carbery, Towards Homosexual Equality in Australian Criminal Law – a Brief History’, rev. edn, Australian Lesbian & Gay Archives, Melbourne, 2014, p. 11, available at <http://www.alga.org.au/files/towardsequality2ed.pdf>, accessed April 1 2019. |

| 19 | ibid., p. 12. |

| 20 | Adams, op. cit., p. 8. |

| 21 | ACON, op. cit., p. 11. |

| 22 | See ‘Ben Winsor, ‘A Definitive Timeline of LGBT+ Rights in Australia’, SBS Sexuality, 12 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/08/12/definitive-timeline-lgbt-rights-australia>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 23 | McKinnon, op. cit., pp. 225, 227. |

| 24 | Ricardo Peach, ‘Queer Cinema as a Fifth Cinema in South Africa and Australia’, PhD thesis, University of Technology Sydney, 2005, pp. 212–3. |

| 25 | Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit. |

| 26 | ibid. |

| 27 | Samantha Searle, Queer-ing the Screen: Sexuality and Australian Film and Television, The Moving Image series, no. 5, ATOM, St Kilda, Vic., 1997, p. 7. |

| 28 | B Ruby Rich, ‘Collision, Catastrophe, Celebration: The Relationship Between Gay and Lesbian Film Festivals and Their Publics’, GLQ: A Journal of Gay and Lesbian Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, 1999, pp. 83–4. |

| 29 | Carbery, op. cit., p. 3. |

| 30 | Digby Duncan, interview with Tina Kaufman, Filmnews, vol. 10, no. 6, June 1980. |

| 31 | Rebecca Beirne, ‘Screening the Dykes of Oz: Lesbian Representation on Australian Television’, in Sara E Cooper (ed.), Lesbian Images in International Popular Culture, Routledge, London, 2010. |

| 32 | Duncan, email interview with author, op. cit. |

| 33 | ibid. |

| 34 | See, for example, Livia Albeck-Ripka, ‘In Some Australian Schools, Teachers Can Be Fired for Being Gay’, The New York Times, 18 October 2018, <https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/18/world/australia/gay-schools-teachers-religion.html>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 35 | See Emma Reynolds, ‘Myths Around Safe Schools and Same-sex Marriages Debunked’, News.com.au, 20 September 2017, <https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/gay-marriage/myths-around-safe-schools-debunked/news-story/374b23a137c5c9ac7b63ace15b9806c7>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 36 | Kelli McGraw & Lisa van Leent, ‘Textual Constraints: Queering the Senior English Text List in the Australian Curriculum’, English in Australia, vol. 53, no. 2, 2018, p. 28, available at <https://www.aate.org.au/documents/item/1654>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 37 | Ben Winsor, ‘A Sordid History of the Gay Panic Defence in Australia’, SBS Sexuality, 12 August 2016, <https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/sexuality/agenda/article/2016/08/12/sordid-history-gay-panic-defence-australia>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 38 | Laurence Barber, ‘South Australia to Finally Scrap “Gay Panic” Defence by the End of the Year’, Star Observer, 9 April 2019, <http://www.starobserver.com.au/news/national-news/south-australia/south-australia-to-finally-scrap-gay-panic-defence-by-the-end-of-the-year/180675>, accessed 30 May 2019. |

| 39 | Tony Crandell, quoted in ‘Sydney Mardi Gras: NSW Police Apologise over “78er” Arrests and Bashings’, op. cit. |